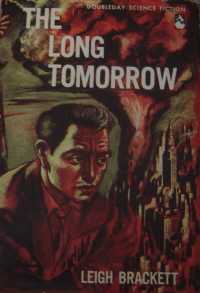

The Long Tomorrow (novel)

|

dust-jacket illustration from the first edition | |

| Author | Leigh Brackett |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction novel |

| Publisher | Doubleday |

Publication date | 1955 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover & Paperback) |

| Pages | 222 pp |

| ISBN | NA |

The Long Tomorrow is a science fiction novel by Leigh Brackett, originally published by Doubleday & Company, Inc in 1955. Set in the aftermath of a nuclear war, it portrays a world where scientific knowledge is feared and restricted.

Plot summary

In the aftermath of a devastating nuclear war, Americans have come to blame technology for the disaster, and far from seeking to recover what was destroyed, are actively opposed to any such attempt.

Religious sects which even before the war opposed modern technology and avoided its use in their daily life have adjusted to the post-apocalypse situation far more easily than anyone else, and feeling themselves vindicated have come to dominate the post-war society. They gained an enormous number of new members, though those families which had been such before the war are honoured and privileged, their special status indicated by slightly different clothing.

All the pre-war American cities have been destroyed in the war, and their re-construction is expressly forbidden. The US Constitution has been amended to now disallow the presence of more than a thousand residents or the existence of more than two hundred buildings per square mile anywhere in the United States.

Len Colter and his cousin Esau are adolescent members of the New Mennonite community of Piper's Run. Against their fathers' wishes, the boys attend a preaching where a trader named Soames is accused and stoned to death for his apparent involvement with a forbidden bastion of technology known as Bartorstown.

Though sickened by the stoning and harshly punished by their fathers, Len and Esau are fascinated by the idea of a community that secretly still holds and harnesses the forbidden technologies. Len's grandmother, a little girl at the time of the destruction, sparks his interest in the technological past with her stories of big, brightly lit cities and little boxes with moving pictures.

Despite even harsher punishment after being caught with a simple radio previously stolen from Soames' wagon, Esau and Len become determined to find their way to the fabled Bartorstown and leave Piper's Run in search of it.

Critical reception

Damon Knight wrote of the novel:[1]

Unhappily, as the story progresses, it seems more and more to support Koestler's assertion that literature and science fiction cancel each other out. Most of the book, particularly the early part, is compellingly written, but not speculative... as the invented elements of the story grow more important, the vision dims... This novel illustrates a problem which science fiction writers are going to have to solve before long: how to write honestly about a mildly speculative future without dragging in pseudoscientific props by the cartload.

Writing in the New York Times, J. Francis McComas described The Long Tomorrow as "Brackett's best novel to date [and] awfully close to being a great work of science fiction." He declared that "Brackett has written a moving but always objective account of the ever-recurring clash between action and reaction in human thought and feeling."[2] Galaxy reviewer Floyd C. Gale praised the novel as a "powerful and sensitive opus."[3] In 2012 the novel was included in the Library of America two-volume boxed set American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s, edited by Gary K. Wolfe.[4] In July 2012, io9 included the book on its list of "10 Science Fiction Novels You Pretend to Have Read".[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Knight, Damon (1967). In Search of Wonder. Chicago: Advent.

- ↑ "In the Realm of the Spaceman", The New York Times Book Review, October 23, 1955, p.30

- ↑ "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf", Galaxy Science Fiction, March 1955, p.97

- ↑ Dave Itzkoff (July 13, 2012). "Classic Sci-Fi Novels Get Futuristic Enhancements from Library of America". Arts Beat: The Culture at Large. The New York Times. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ↑ Anders, Charlie Jane (July 10, 2012). "10 Science Fiction Novels You Pretend to Have Read (And Why You Should Actually Read Them)". io9. Retrieved June 5, 2013.