The Lion Sleeps Tonight

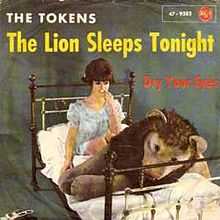

| "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Single by The Tokens | |||||||

| from the album The Lion Sleeps Tonight | |||||||

| B-side | "Dry Your Eyes" | ||||||

| Released | 1961 | ||||||

| Genre | Rhythm and blues, doo-wop, world | ||||||

| Length | 2:41 | ||||||

| Label | RCA | ||||||

| Writer(s) |

Solomon Linda Hugo Peretti Luigi Creatore George David Weiss Albert Stanton | ||||||

| |||||||

"The Lion Sleeps Tonight", also known as "Wimoweh", "Wimba Way" or "Awimbawe", is a song written and recorded by Solomon Linda with the Evening Birds[1] for the South African Gallo Record Company in 1939, under the title "Mbube". Composed in Zulu, it was adapted and covered internationally by many 1950s pop and folk revival artists, including Pete Seeger, the Weavers, Jimmy Dorsey, Yma Sumac, Miriam Makeba and the Kingston Trio. In 1961, it became a number one hit in the United States as adapted in English by the doo-wop group the Tokens. It went on to earn at least US$15 million in royalties from cover versions and film licensing.

In the mid-nineties, it became a pop "supernova" when licensed to Walt Disney for use in the film The Lion King, its spin-off TV series and live musical, prompting a lawsuit in 2004, on behalf of the descendants of Solomon Linda.

History

"Mbube" (Zulu: lion) was written in the 1920s, by Solomon Linda, a South African singer of Zulu origin, who later worked for the Gallo Record Company in Johannesburg, as a cleaner and record packer. He spent his weekends performing with a music group, the Evening Birds, and it was at Gallo Records, under the direction of black producer Griffiths Motsieloa, that Linda and his fellow musicians recorded several songs including "Mbube," incorporating a call-response pattern common among many Sub-Saharan African ethnic groups, including the Zulu.

According to journalist Rian Malan:

"Mbube" wasn't the most remarkable tune, but there was something terribly compelling about the underlying chant, a dense meshing of low male voices above which Solomon yodelled and howled for two exhilarating minutes, occasionally making it up as he went along. The third take was the great one, but it achieved immortality only in its dying seconds, when Solly took a deep breath, opened his mouth and improvised the melody that the world now associates with these words:

Issued by Gallo as a 78 recording in 1939, and marketed to black audiences,[2] "Mbube" became a hit and Linda a star throughout South Africa. By 1948, the song had sold 100,000 copies in Africa and among black South African immigrants in Great Britain, and had lent its name to a style of African a cappella music that evolved into isicathamiya (also called mbube), popularized by Ladysmith Black Mambazo.[3]

In 1961, two RCA producers, Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore, hired Juilliard-trained musician and lyricist George David Weiss to arrange a pop music cover of "Wimoweh", as the B-side of a 45-rpm single called "Tina" sung by the teenage doo-wop group The Tokens. Weiss wrote the English lyrics: "In the jungle, the mighty jungle, The lion sleeps tonight..." and "Hush, my darling, don't fear, my darling..."

Weiss also brought in soprano Anita Darian to reprise Yma Sumac's Exotica version, before, during and after the saxophone solo.[4] Issued by RCA in 1961, "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" rocketed to number one[4] on the Billboard Hot 100. Weiss' Abilene Music Inc., was the publisher of this arrangement, and listed "Albert Stanton" (a pseudonym for Al Brackman, the business partner of Pete Seeger's music publisher, Howie Richmond), as one of the song's writers or arrangers. This earned TRO/Folkways a share of the author's half of the royalty earnings.[5]

Copyright issues

Social historian Ronald D. Cohen writes, "Howie Richmond copyrighted many songs originally in the public domain [sic] but now slightly revised to satisfy Decca and also to reap the profits."[6] Canadian writer Mark Steyn, on the other hand, attributes the invention of the pseudonym "Paul Campbell" to Pete Seeger.[7] Howie Richmond's claim of author's copyright could secure both the songwriter's royalties and his company's publishing share of the song's earnings.[1]

Pete Seeger expressed concerns about the copyright laws associated with the song. Folkways Records founder Moe Asch frequently voiced the belief that traditional songs could not and should not be copyrighted at all.[8] Although Linda's name was listed as a performer on the record, The Weavers assumed that the song was traditional. The Weavers' managers and publisher and their attorneys, however, knew otherwise, because they were contacted by and reached an agreement with Eric Gallo of South Africa. They attempted to maintain, however, that South African copyrights were not valid because South Africa was not a signatory to U.S. copyright law and were hence "fair game."[1] As early as the 1950s, when Linda's authorship was made clear, Seeger sent him a donation of one thousand dollars and instructed TRO/Folkways to henceforth donate his (Seeger's) share of authors' earnings. The folksinger, however, who was not a businessman, trusted his publisher's word of honor and neglected or was unable to see to it that these instructions were carried out.[1]

In 2000, South African journalist Rian Malan wrote a feature article for Rolling Stone magazine in which he recounted Linda's story and estimated that the song had earned $15 million for its use in the movie The Lion King alone. The piece prompted filmmaker François Verster to create the Emmy-winning documentary A Lion's Trail (2002) that told Linda's story while incidentally exposing the workings of the multi-million dollar corporate music publishing industry.[9]

In July 2004, as a result of the publicity generated by Malan's Rolling Stone article and the subsequent filmed documentary, the song became the subject of a lawsuit between Solomon Linda's estate and Disney, claiming that Disney owed $1.6 million in royalties for the use of "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" in the film and musical stage productions of The Lion King.[10] At the same time, The Richmond Organization began to pay $3,000 annually into Linda's estate. In February 2006, Linda's descendants reached a legal settlement with Abilene Music Publishers, who held the worldwide rights and had licensed the song to Disney, to place the earnings of the song in a trust.[11][12]

Selected list of recorded versions

"Mbube"

- 1939 Solomon Linda and the Evening Birds[13]

- 1951 In the first film adaptation of Cry, the Beloved Country

- 1960 Miriam Makeba, on Miriam Makeba

- 1988 Ladysmith Black Mambazo, as "Mbube", during opening sequence of movie Coming to America (but not on the soundtrack album)

- 1991 The Elite Swingsters Featuring Dolly Rathebe, as "Mbube" on Woza!

- 1994 Ladysmith Black Mambazo, as "Mbube (The Lion Sleeps Tonight)", on Gift of the Tortoise

- 1996 Soweto String Quartet, as "Imbube" on Renaissance

- 2005 Soweto Gospel Choir, as "Imbube" on Blessed

- 2006 Ladysmith Black Mambazo, as "Mbube", on Long Walk to Freedom

- 2007 CH2 and Soweto String Quartet, as "Imbube" on Pap & Paella

- 2010 Angélique Kidjo, as "Mbube" on Õÿö

"Wimoweh"

- 1952: The Weavers: US #6

- 1952: Jimmy Dorsey

- 1952: Yma Sumac

- 1957: The Weavers, live.

- 1959: Bill Hayes (on Kapp Records)

- 1959: The Kingston Trio

- 1961: Karl Denver Trio: UK #4

- 1962: Bert Kaempfert on That Happy Feeling

- 1964: Chet Atkins

- 1993: Nanci Griffith with Odetta, on Other Voices, Other Rooms

- 1994: Roger Whittaker, on Roger Whittaker Live!

- 1994: Manu Dibango and Ladysmith Black Mambazo, on Waka Afrika

- 1998: Pete Seeger on For Kids And Just Plain Folks

- 1999: Desmond Dekker on Halfway To Paradise

"The Lion Sleeps Tonight"

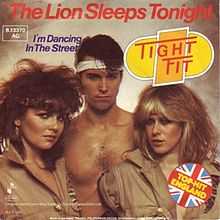

| "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

The Lion Sleeps Tonight | ||||

| Single by Tight Fit | ||||

| from the album Tight Fit | ||||

| Released | January 1982 | |||

| Genre | Pop | |||

| Length | 3:18 | |||

| Label | Jive | |||

| Writer(s) |

Hugo Peretti Luigi Creatore George David Weiss Albert Stanton Solomon Linda | |||

| Producer(s) | Tim Friese-Greene[14] | |||

| Certification | Gold | |||

| Tight Fit singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

- 1961: The Tokens: US #1, UK #11

- 1962: Henri Salvador (French language: "Le lion est mort ce soir", which translates into English as "The Lion Died Tonight") FR #1

- 1965: The New Christy Minstrels

- 1968: The Tremeloes, on Silence is Golden

- 1971: Eric Donaldson

- 1972: Robert John: US #3

- 1972: Dave Newman: UK #34

- 1974: Ras Michael and the Sons of Negus, as "Rise Jah Jah Children (The Lion Sleeps)"

- 1975: Brian Eno, on The Ambivalent Collection

- 1979: The Stylistics

- 1980: Passengers

- 1982: Tight Fit: UK #1,[15] NL #1[16] This version has sold over a million copies in the UK.[17]

- 1982: The Nylons

- 1989: Sandra Bernhard

- 1991: Hotline & P.J. Powers, on The Best of

- 1992: Talisman, on A Capella

- 1992: They Might Be Giants with Laura Cantrell, interpolated into "The Guitar (The Lion Sleeps Tonight)"

- 1993: Pow woW: FR #1, cover of Salvador's version.

- 1993: R.E.M.: B-side of "The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite" and on The Automatic Box (Disc 3).

- 1993: The Nylons

- 1994: Dennis Marcellino

- 1994: Tonic Sol-Fa

- 1995: Lebo M. for Rhythm of the Pride Lands, an album with songs inspired by the music of The Lion King

- 1997: 'N Sync: B-side of "For the Girl Who Has Everything"

- 1997: The Muppets, on an episode of Muppets Tonight

- 1998: Helmut Lotti, on Out of Africa

- 1998: The Undertones, on 8 Degrees and Rising

- 1990's: The Streetnix

- 2001: Baha Men featuring Imani Coppola, sampled the chrous in the song "You All Dat" on Who Let the Dogs Out

- 2001: Rockapella

- 2001: Scallwags, on Punk Chartbusters

- 2001: Straight no chaser

- 2002: Mango Groove, on Eat A Mango

- 2004: Daniel Küblböck

- 2005: The Mavericks

- 2009: Melo-M, on Around the World

- 2009: Russell Levia, on Morningtown Ride

- 2010: Cool Down Cafe Feat Gerard Joling, on Goud

- 2010: Voices Unlimited, on Africapella

- 2010: Tony Teran, on The Song's Been Sung

- 2015: The Eclectics: AUS #1

Charted singles

The Tokens

| Chart (1961) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard Top 100 Singles | 1 |

| US Billboard R&B Singles | 7 |

| Australia Kent Music Report | 15 |

| Belgian Ultratop 50 | 6 |

| German Media Control Charts | 23 |

| U.K. Singles Charts | 11 |

Robert John

| Chart (1972) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard Top 100 Singles | 3 |

| US Billboard Adult Contemporary | 6 |

| Canadian RPM Top Tracks | 15 |

| Canadian RPM Adult Contemporary | 17 |

| German Singles Charts | 40 |

Tight Fit

| Chart (1982) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| U.K. Singles Charts | 1 |

| Ö3 Austria Top 40 | 8 |

| Belgian Ultratop 50 | 1 |

| German Media Control Charts | 3 |

| Dutch Singles Charts | 1 |

| Irish Singles Charts | 1 |

| New Zealand Singles Charts | 3 |

| Swedish Sverigetopplistan Charts | 17 |

| Swiss Ultratop Charts | 8 |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Malan, Rian. "In the Jungle". Longform.org. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ↑ Cad, Saint. "Top 10 Famous Songs With Unknown Originals". listverse.com. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ Frith, Simon, Popular music: critical concepts in media and cultural studies, Volume 4], London : Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-0-415-33270-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Show 18 - Blowin' in the Wind: Pop discovers folk music. [Part 1] : UNT Digital Library". Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu. 18 May 1969. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ↑ Royalty earnings are customarily divided 50–50 between a song's composers and the music publisher, though other combinations are possible. Rian Malan writes that when Howie Richmond heard "The Lion Sleeps" on the radio in 1961, he contacted Weiss, Peretti, and Creatore and threatened to sue them. Malan describes TRO, Peretti, Creatore, and Weiss as cutting a deal that excluded mention of Linda altogether (and The Weavers, too, apparently, though they may have gotten something through "Paul Campbell"). Malan writes that in the settlement: "TRO received the full fifty percent publisher's cut. [Writer-producers] Huge and Luge and Weiss [and "co-writer" "Albert Stanton", too] were happy. The only person who lost out was Linda, who was not even mentioned in any document: The new copyright described "Lion" as "based on a song by 'Paul Campbell'" (see Malan, "In the Jungle", 2000, Rolling Stone).

- ↑ Ronald D. Cohen, Rainbow Quest: the Folk Music Revival and American Society (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002), page 71. Contrary to what Ronald D. Cohen implies, however, the U.S. copyright law is structured so that Howie Richmond's music publishing companies were financially separate from Decca. In return for a percentage of the profits, music publishing companies, a holdover from the sheet music era, collect and distribute royalties, license compositions, and monitor where they are used. They also secure commissions for music and promote existing compositions to recording artists, film, and television, and collect what are called "mechanical license" fees. To spare the expense of dealing with music publishers, many modern performers have learned to incorporate themselves as their own music publishers.

- ↑

- ↑ See, for example, Moe Asch's many declarations that in his opinion the people's "right to know" superseded copyright law in Richard Carlin's, Worlds of Sound: The Story of Smithsonian Folkways (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Publications, 2008), pp. 74–77, and passim.

- ↑ "National Television Academy Presents 27th Annual News & Documentary Emmy Awards" (press release), September 25, 2006.

- ↑ "3rd Ear Music Forum - Mbube - Mickey Mouse Under House Arrest in SAfrica?". 3rdearmusic.com. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ↑ "Penniless singer's family sue Disney for Lion King royalties". Telegraph. 30 October 2004. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

The family of a South African performer and composer who died in poverty are suing Disney for £900,000 over claims that the company used of one of his tunes in their hit film and stage show The Lion King. Solomon Linda, who died in 1962 aged 61, wrote "Mbube" while eking out a living as a beer-hall singer in Johannesburg. The tune was later used for the hit single "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" and in a 20-second sequence of the 1994 film featuring the voices of Jeremy Irons, Rowan Atkinson and Whoopi Goldberg.

- ↑ "It's a Lawsuit, a Mighty Lawsuit". Time (magazine). 25 October 2004. Retrieved 14 February 2007.

It is one of the most naggingly catchy tunes in pop music – and, it turns out, one of the most controversial. "The Lion Sleeps Tonight", featured in Disney blockbuster The Lion King, is based on the 1939 song "Mbube", written by South African musician Solomon Linda. But Linda, a cleaner at a Johannesburg record company when he wrote the song, received virtually nothing for his work and died in 1962 with $25 in his bank account. His family is suing Disney for $1.5 million. Disney says it will fight the suit, but it's already paying off. Though not named in the suit, U.S. music-publishing house TRO/Folkways last month admitted it had not been paying royalties on a version of the song, and promises to give some $3,000 a year to the Linda family and to finance a memorial to the unsung songwriter.

See also, Dean, Owen, "Copyright in the Courts: The Return of the Lion", WIPO Magazine, April 2006. - ↑ "The Lion Sleeps Tonight 1939 : Linda Solomon, The Evening Birds". Archive.org. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ↑ Rice, Jo (1982). The Guinness Book of 500 Number One Hits (1st ed.). Enfield, Middlesex: Guinness Superlatives Ltd. p. 222. ISBN 0-85112-250-7.

- ↑ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 406. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ↑ De Nederlandse Top 40, week 16, 1982 |accessdate=2008-02-18

- ↑ Ami Sedghi (4 November 2012). "UK's million-selling singles: the full list". Guardian. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

External links

- Solomon Linda, Songwriter Who Penned ‘The Lion,’ Finally Gets His Just Desserts

- Sample of Mbube performed by Solomon Linda's Original Evening Birds (WMA Stream).

- NPR: All Things Considered: Family of 'Lion Sleeps Tonight' Writer to Get Millions

- Telegraph: Penniless singer's family sue Disney for Lion King royalties

- The Lion Sleeps Tonight. BBC World Service Documentary by Paul Gambaccini first broadcast 16th July 2010

| Preceded by "Please Mr. Postman" by The Marvelettes |

Billboard Hot 100 number one single (The Tokens version) December 18, 1961 (three weeks) |

Succeeded by "The Twist" by Chubby Checker |

| Preceded by "Town Called Malice" by The Jam |

UK Singles Chart number one single (Tight Fit version) 28 February 1982 - 20 March 1982 |

Succeeded by "Seven Tears" by Goombay Dance Band |