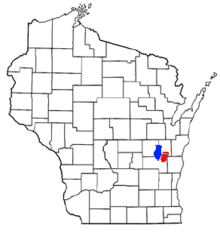

The Holyland (Wisconsin)

The Holyland is an American region located mainly in northeastern Fond du Lac County, Wisconsin and southern Calumet County.[1] The area is known for its distinctive agricultural landscape, a close-knit community life, and deep Roman Catholicism brought by Germans who began settling the region in the 1840s.[2] The area has been studied as an example of chain migration.[3] It has been called "The Holyland" since at least 1898.[3]

Location

The Holyland area is located in the region east of the southern end of Lake Winnebago and it crosses political boundaries. It is primarily in Fond du Lac and Calumet counties, with a small area in the northwest corner of Sheboygan County.[2] Towns include Taycheedah, Calumet, and all of Marshfield in Fond du Lac County and Brothertown and New Holstein in Calumet County.[2] Communities include Calvary, Charlesburg, Jericho, Johnsburg, Marytown,[4] Mount Calvary, St. Anna, St. Cloud, St. Joe, and St. Peter.[1][5][6] Eden, Wisconsin is not considered part of this region.[5]

History

Origin

Reverend Casper Rehrl was a missionary who founded Roman Catholic churches in the area. Between 1841 and 1870, ten German Catholic parishes were established in the Holyland.[7] The church sites, which were mostly named after saints, eventually grew into communities.[8] German-speaking Roman Catholics immigrated to the Holyland from the Vulkaneifel region of Rhenish Prussia in the late 19th century.[1] Many of the immigrants came from the municipalities of Daun and Adenau.[2] Smaller communities and hamlets in that area include Kaperich, Nitz, Kirsbach, and Mürlenbach.[2] Because the area had limited land available, experienced periodic crop failures, and was undergoing changes to its industry, immigrants left to find better economic conditions.[3] According to M. Beth Schlemper's translation of Joseph Mergen's work Die Amerika Auswanderung aus dem Landkreise Daun, "[In 1838], the yield of potatoes was only average in quantity. The wine harvest hardly reached a fourth of a usual, average year and was at the same time of poorer quality. The fruit completely failed".[2] Land had been divided among heirs for so many generations that farms were too small to be viable.[2]

In another region of Prussia, Schleswig-Holstein, Denmark to the north was battling Prussia to the south in the 1840s.[9] Emigrants from that area also found their way to the Holyland, especially in the area around New Holstein.

Settlement in Wisconsin

Immigrants began settling in Wisconsin in the 1830s.[3] To get to Wisconsin, they typically traveled across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City, then up the Hudson River to the Erie Canal, and followed the Erie Canal across New York state to Buffalo. From Buffalo they traversed the Great Lakes to Wisconsin. Those who settled the Holyland traveled across forested land to a settlement in Calumetville.[9] Calumetville's hotel had been established by George White in 1835. It was on the only road through the region, a north-south military road.[9] White became friends with immigrant Ferdinand Ostenfeld, who described the poor conditions in his original homeland. White asked Ostenfeld to return to his original homeland with him in late 1847 to convince others to come to America. White later sold land to some of these immigrants.[9]

A ship left Prussia on April 2, 1848 carrying 198 passengers, with almost every passenger an immigrant from Prussia or Schleswig-Holstein.[9] The group arrived in New York on May 12. Their Great Lakes vessel arrived in Sheboygan on May 22 and they arrived at Calumetville on May 25.[9]

A second settlement formed at Johnsburg, and within two years the group had founded a church called St. Johannes Gemeinde (German for St. John's Congregation, now St. John the Baptist).[2] Johnsburg church historian Benjamin Blied said, "Most of [the immigrants], more or less antagonistic to being governed by Protestant Prussia ever since the defeat of Napoleon, left their homes along the Mosel River between Trier and Koblenz hoping primarily to better their economic condition in the new world." Over the next few years, Johnsburg became the core for the growing area.[2] A second wave of immigrants arrived in the 1860s and 1870s, some with families and friends from the first wave.[3] The Capuchin religious order selected the Holyland for its first permanent American settlement.[8] They founded a seminary (now St. Lawrence Seminary High School) in 1856 to train young men to become priests.[8] Between 1841 and 1870, eleven parishes were founded in the Holyland.[2] They were built as territorial churches to serve the people in the vicinity, not as national churches to serve immigrants of a particular ethnicity.[2]

The introduction of the Sheboygan-Fond du Lac Railroad helped develop the communities, but the railroad declined after trucking became more cost effective.[6]

Chain migration

Chain migration is a process whereby early immigrants to an area send back information encouraging their relatives and friends to immigrate. An example is this letter from Michael Rodenkirch from December 26, 1846,

Dear Mother, if you are still alive and if you were here, I do not think you would want to return to German; and you, my sisters and brothers, I would like to wish you all over here, if I knew you would be as contented as I am here. I have never regretted my journey here... I have spoken to many in the state who have been here for a few years and they now have enough to live on and would never wish themselves back in Germany. At least here a person has a better life.[2]—Michael Rodenkirch, English translation by Sister Julianna, Mount Mary College

Another influential item was Carl de Haas's 1848 report Nordamerika, Wisconsin, Calumet: Winke für Auswanderer (Calumet, Wisconsin, North America: A Prospect for Emigrants) which was published in Elberfeld, Germany. After living in Calumet (now Calumetville) for six months, he prefaced the report, "Upon my departure from Germany I faithfully promised friends and acquaintances that I would send them within the year, a complete report of my observations during the journey from Elberfeld, Germany to Calumet, Wisconsin, and particularly of my experiences here."[2] His account included detailed information for those considering immigrating, including provisions to bring along, conditions in Wisconsin, travel advice, and description of the land and wildlife. He described which ships to take from Germany and how to purchase and use farmland after arrival in Wisconsin.[2]

Museum

The history of the Holyland region is preserved in the Malone Area Heritage Museum.[6] The museum is located in two buildings in Malone.[6] One of these buildings was the train depot for the community; it is the only remaining depot left from the railroad that is not being used as a commercial structure.[6] Malone, originally named St. John, was renamed after railroad official H. T. Malone.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "German-Catholic immigrants shaped life, communities in east-central Wisconsin". University of Wisconsin–Madison. 2003-02-25. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Schlemper, M. Beth (2006). "Borders of the Holyland of east-central Wisconsin". In Ostergren, Robert C.; Kluge, Cora Lee; Bungert, Heike. Wisconsin German Land and Life. Madison, Wisconsin: Max Kade Institute for German-American Studies. pp. 189–205. ISBN 0-924119-26-8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Schlemper, M. Beth (Spring 2003). "Building identity in the Holyland" (PDF). Max Kade Institute Friends Newsletter. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- ↑ The History of Marytown, Wisconsin

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Schlemper, M. Beth (2004). "The Regional Construction of Identity and Scale in Wisconsin's Holyland". Journal of Cultural Geography 22.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Kleine, Katie (November 2, 2008). "Museum revives Holyland history: from Eden to Jericho". Action Sunday. pp. A1. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ↑ Schlemper, M. B. (2007). "From the Rhenish Prussian Eifel to the Wisconsin Holyland: immigration, identity and acculturation at the regional scale". Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2): 377–402. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.05.001.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Betz, Maureen; Ebert, John (1999). Fond du Lac County: The Gathering Place. Fond du Lac, Wisconsin: Action Printing. p. 53.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Wulff, Eugene C. The New Holstein Story. pp. 6–9.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||