The Grove Plantation

|

Call-Collins Mansion at The Grove | |

| |

| |

| Location | Leon County, Florida |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Tallahassee |

| Coordinates | 30°27′1″N 84°16′55″W / 30.45028°N 84.28194°WCoordinates: 30°27′1″N 84°16′55″W / 30.45028°N 84.28194°W |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 72000335[1] |

| Added to NRHP | June 13, 1972 |

The Grove was a modest cotton plantation established by Richard Keith Call, future territorial governor, in the 1830s in central Leon County, Florida. Call also owned Orchard Pond Plantation, which had more than 8,000 acres. In 1860, he was the third-largest slaveholder in the county.

In 1942, then Senator LeRoy Collins purchased the Grove. His wife was Mary Call Darby, a great-granddaughter of Call. Later the Collinses sold the home and remaining land to the state for eventual use as a museum. Now called the Call-Collins Mansion at the Grove, the property is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. LeRoy Collins is buried at The Grove Cemetery.

Background

Constructed between 1826 and 1836 by Richard Keith Call and ten skilled African-American slaves, the Call-Collins Mansion at The Grove is a Greek Revival-style house that was part of a one square mile, or 640 acres (260 ha) plantation located in central Leon County, Florida. Call also owned Orchard Pond Plantation, a nearly 9,000-acre agricultural plantation located north of Tallahassee on the shores of Lake Jackson. Call was a military and political protege of Andrew Jackson, and his mansion at the Grove was strongly influenced by the architectural styling of Jackson's The Hermitage.

In addition to its simplistically elegant Georgian floor plan, the house includes a raised basement, which was constructed to protect inhabitants in the event of an Indian attack and to also provide a cooler, less formal cooking and dining space. Having served twice as Florida's territorial governor (1836–39, 1841–44) and as a battlefield commander during the Second Seminole War, Call lived at The Grove until 1850, when he deeded the property to his oldest surviving daughter, Ellen Call Long. Call died in 1862, days after learning of the death of his favorite nephew on the battlefield at Shiloh.[2]

The period from 1850 through the 1930s was one marked by female ownership and resourceful economic entrepreneurship at The Grove. The home was the site of a silkworm farm, a boarding and guest house, and Reinette Long Hunt (daughter of Ellen Call Long) taught art and dance classes on the property. A New Year's Eve fire in 1934 caused some damage to the home but was confined to the attic.

In 1942, The Grove was purchased by then Senator LeRoy Collins and his wife, Mary Call Darby, a great-granddaughter of Call. The Collins family rescued The Grove and its grounds from disrepair. Collins was central in the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and was instrumental in the peaceful integration of Florida's public schools. He was also a central figure in the creation of Florida's first Historic Preservation initiatives and statutes. In 1985, The Collins family sold the home and remaining 10.33 acres (4.18 ha) to the state for eventual use as a museum. Richard Keith Call and his wife, Mary Kirkman Call, as well as Mary Call Collins and LeRoy Collins, are buried in the cemetery at The Grove.[3]

Location

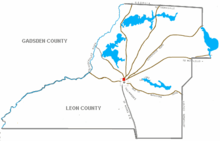

The Grove is located adjacent to the Governor's Mansion in what is now mid-town Tallahassee. Its original acreage once extended from Brevard Street on the south to Tharpe Street and Lake Ella on the north.

Today

The Grove falls under the protection of Florida Statute 267.075, Title XVIII, Chapter 267 which states that The Grove be utilized as a house museum of history for the educational benefit of the citizens of this state. The Grove Advisory Council oversees and advises the Florida Division of Historical Resources on the operation, maintenance, preservation, and protection of the The Grove or Call/Collins House.

The Florida Division of Historical Resources renovated The Grove to adapt it for use as a historic house museum and site of the Call-Collins Center for Principled Public Service. It is intended to build on the legacy of Call and Collins to provide new forums for dialogue and learning outside of the classroom.[4] In addition to the development of interpretive programs and exhibits, project architects and engineers using state of the art restoration and rehabilitation techniques ensured that The Grove in 2012 qualified as one of three LEED-certified historic house museums in the United States. The others are the Mark Twain Boyhood home in Hannibal, Missouri, and FDR's Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia.[5]

Gallery

-

Call-Collins Mansion, 1880

-

May Day Party at The Grove, 1960

References

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2010-07-09.

- ↑ Call/Brevard Family Papers, Florida Memory Project .

- ↑ LeRoy Collins, Forerunners Courageous, 1971

- ↑ The Grove - A Brief History of the Site

- ↑ LEED Projects & Case Studies Directory

Sources

- Menton, Jane Aurell. The Grove: A Florida Home Through Seven Generations. Tallahassee: Sentry Press, 1998.

- Collins, Thomas LeRoy. Forerunners Courageous: Stories of Frontier Florida (1970)

- Tallahassee Democrat, August 1, 2006

- Florida Senate statutes

- Florida Division of Historical Resources "A Brief History of the Grove"

- Paisley, Clifton; From Cotton To Quail, University of Florida Press, c1968.

Further reading on Richard Keith Call

- Edward E. Baptist, Creating an Old South: Middle Florida’s Plantation Frontier before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002);

- Caroline Mays Brevard, “Richard Keith Call,” Florida Historical Quarterly, I, October 1908: 8-20;

- Kate Denison, “Richard Keith Call: Promoter of the Florida Wilderness,” (Florida Living, November 1992: 37);

- Herbert J. Doherty, Richard Keith Call, Southern Unionist (Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1961); Sidney Walter Martin, “Richard Keith Call: Florida Territorial Leader” (Florida Historical Quarterly, XXI, January 1943: 331-351). For a general overview of political context of Call’s governorship, see Arthur W. Thompson’s Jacksonian Democracy on the Florida Frontier (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1961).

Further reading on LeRoy Collins

- Sandy D’Alemberte and Frank Sanchez, “Tribute to a Great Man: LeRoy Collins in Florida State" University Law Review 19 (Fall 1991: 255-64);

- Tom R. Wagy, Governor LeRoy Collins of Florida (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985)

- Martin Dyckman’s Floridian of His Century: The Courage of LeRoy Collins (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2006)

- LeRoy Collins Papers at Florida State University (http://www.fsu.edu/~speccoll/leroy/lerocoll.htm) and Collins correspondence at the State of Florida Archives in Tallahassee (http://dlis.dos.state.fl.us/barm/rediscovery/default.asp)