The Great Naktong Offensive

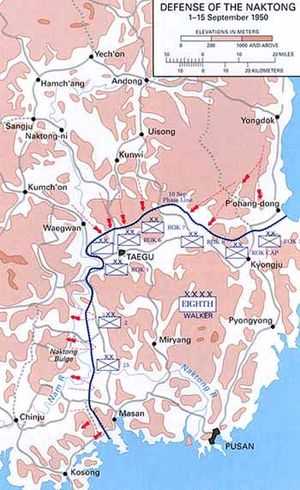

The Great Naktong Offensive was a North Korean military offensive against United Nations and Republic of Korea forces early in the Korean War, taking place from September 1–15, 1950. It was the North Korean People's Army's unsuccessful final bid to break the Pusan Perimeter established by the United Nations Command.

For the first several months of the war, the North Korean Army successfully defeated and pushed back the United Nations (UN) forces south at each encounter. However, by August the UN troops (which were composed mostly of troops from the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK) and Republic of Korea (ROK) had been forced into the 140-mile (230 km) Pusan Perimeter on the southeast tip of the Korean peninsula. For the first time, the UN troops formed a continuous line which the North Koreans could neither flank nor overwhelm with superior numbers. North Korean offensives on the perimeter were stalled and by the end of August all momentum was lost. Seeing the danger in a prolonged conflict along the perimeter, the North Koreans sought a massive offensive for September to collapse the UN line.

The North Koreans subsequently planned a simultaneous offensive for their entire army along five axes of the perimeter; and on September 1 intense fighting erupted around the cities of Masan, Kyongju, Taegu, Yongch'on and the Naktong Bulge. What followed was two weeks of extremely brutal fighting as the two sides vied to control the routes into Pusan. Initially successful in some areas, the North Koreans were unable to hold their gains against the numerically and technologically superior UN force. The North Korean army, again stalled at the failure of this offensive, was subsequently destroyed in the UN counterattack at Inchon.

Background

From the outbreak of the Korean War following the invasion of South Korea by the North in June 1950, the North Korean People's Army had enjoyed superiority in both manpower and equipment over the Republic of Korea Army and the United Nations forces dispatched to South Korea to prevent it from collapsing.[1] The North Korean strategy was to aggressively pursue UN and ROK forces on all avenues of approach south and to engage them, attacking from the front and initiating a double envelopment of both flanks of the unit, which allowed the North Koreans to surround and cut off the opposing force, which would then be forced to retreat in disarray, often leaving behind much of its equipment.[2] From their initial June 25 offensive to fights in July and early August, the North Koreans used this strategy to effectively defeat any UN force and push it south.[3] However, with the establishment of the Pusan Perimeter in August, the UN troops held a continuous line which the North Koreans could not flank, and their advantages in numbers decreased daily as the superior UN logistical system brought in more troops and supplies to the UN army.[4]

When the North Koreans approached the Pusan Perimeter on August 5, they attempted the same frontal assault technique on the four main avenues of approach into the perimeter. Throughout August, the NK 6th Division, and later the NK 7th Division engaged the US 25th Infantry Division at the Battle of Masan, initially repelling a UN counteroffensive before attacking Komam-ni[5] and Battle Mountain.[6] These attacks stalled as UN forces, well equipped and with large standing units of reserves, repeatedly repelled North Korean attacks.[7] North of Masan, the NK 4th Division and the US 24th Infantry Division sparred in the Naktong Bulge area. In the First Battle of Naktong Bulge, the North Korean division was unable to hold its bridgehead across the river as large numbers of US reserves were brought in to repel it, and on August 19, the NK 4th Division was forced back across the river with 50 percent casualties.[8][9] In the Taegu region, five North Korean divisions were repulsed by three UN divisions in several attempts to attack the city during the Battle of Taegu.[10][11] Particularly heavy fighting took place at the Battle of the Bowling Alley where the NK 13th Division was almost completely destroyed in the attack.[12] On the east coast, three more North Korean divisions were repulsed by the South Koreans at P'ohang-dong during the Battle of P'ohang-dong.[13] All along the front, the North Korean troops were reeling from these defeats, the first time in the war their strategies were failing.[14]

By the end of August the North Korean troops had been pushed beyond their limits and many of the original units were at far reduced strength and effectiveness.[4][15] Logistic problems racked the North Korean Army, and shortages of food, weapons, equipment and replacement soldiers proved devastating for the North Korean units.[2][16] By late August, the UN command had more combat soldiers in Korea than the North Koreans did, and UN superiority over the air and sea meant the North Koreans were at a disadvantage which was growing daily.[4] North Korean tank losses had been in the hundreds, and they had fewer than 100 tanks by the time of the Pusan Perimeter fight, to the Americans' 600 tanks. By the end of August the North Koreans' only remaining advantage was their initiative. However, the North Korean force retained high morale and enough supply to allow for a large-scale offensive.[3]

Prelude

In planning its new offensive, the North Korean command decided any attempt to flank the UN force was impossible thanks to the support of the UN navy.[12] Instead, they opted to use a frontal attack to breach the perimeter and collapse it as the only hope of achieving success in the battle.[4] Fed with intelligence from the Soviet Union the North Koreans were aware that the UN forces were building up along the Pusan Perimeter and that it must conduct an offensive soon or it could not win the battle.[17] A secondary objective was to surround Taegu and destroy the UN and ROK units in that city. As part of this mission, the North Korean units would first cut the supply lines to Taegu.[15]

North Korean planners enlarged the North Korean force in anticipation of a new offensive.[18] The army, originally numbering 10 divisions in two corps, was enlarged to 14 divisions with several independent brigades.[19] The new troops were brought in from reserve forces from North Korea.[20] Marshal Choe Yong Gun served as deputy commander of the North Korean Army, with General Kim Chaek in charge of the Front Headquarters.[17] Beneath them were the NK II Corps in the east, commanded by Lieutenant General Kim Mu Chong, and NK I Corps in the west, under Lieutenant General Kim Ung. II Corps controlled the NK 10th Division, NK 2nd Division, NK 4th Division, NK 9th Division, NK 7th Division, NK 6th Division and NK 105th Armored Division, with the NK 16th Armored Brigade and NK 104th Security Brigade in support. I Corps commanded the NK 3rd Division, NK 13th Division, NK 1st Division, NK 8th Division, NK 15th Division, NK 12th Division, and NK 5th Division with the NK 17th Armored Brigade in support.[19] This force numbered approximately 97,850 men, although a third of it comprised raw recruits, forced conscripts from South Korea, and lacked weapons and equipment.[21][22] By August 31 they were facing a UN force of 120,000 combat troops plus 60,000 support troops.[23]

On August 20, the North Korean commands distributed operations orders to their subordinate units.[17] The North Koreans called for a simultaneous five-prong attack against the UN lines. These attacks would overwhelm the UN defenders and allow the North Koreans to break through the lines in at least one place to force the UN forces back. Five battle groupings were ordered:[21]

- NK 6th and 7th Divisions break through the US 25th Infantry Division at Masan.

- NK 9th, 4th, 2nd, and 10th Divisions break through the US 2nd Infantry Division at the Naktong Bulge to Miryang and Yongsan.

- NK 3rd, 13th, and 1st Divisions break through the US 1st Cavalry Division and ROK 1st Division to Taegu.

- NK 8th and 15th Divisions break through the ROK 8th Division and ROK 6th Division to Hayang and Yongch'on.[24]

- NK 12th and 5th Divisions break through the ROK Capital Division and ROK 3rd Division to P'ohang-dong and Kyongju.

On August 22 the North Korean premier, Kim Il Sung, had ordered his forces to conclude the war by September 1, yet the scale of the offensive did not allow this.[20] Groups 1 and 2 were to begin their attack at 23:30 on August 31, and Groups 3, 4 and 5 would begin their attacks at 18:00 on September 2.[24] The attacks were to closely connect in order to overwhelm UN troops at each point simultaneously, forcing breakthroughs in multiple places that the UN would be unable to reinforce.[17][23] The North Koreans relied primarily on night attacks to counter UN air superiority and naval firepower, with the North Korean generals believing that such attacks would prevent UN forces from firing effectively and result in heavy casualties from friendly fire.[25]

The attacks caught UN planners and troops by surprise.[26] By August 26, the UN troops thought they had destroyed the last serious threats to the perimeter, and anticipated the war ending by late November.[27] ROK units, in the meantime, suffered from low morale as a result of their failures to defend effectively thus far in the conflict, and a cautious US Eighth Army commander Lieutenant General Walton Walker ordered Major General John B. Coulter to the P'ohang-dong area to shore up the ROK I Corps, which was falling apart due to low morale.[28] UN troops were preparing for Operation Chromite, an amphibious assault on the port of Inchon on September 15, and did not anticipate that the North Koreans would mount a serious offensive before then.[26]

Battle

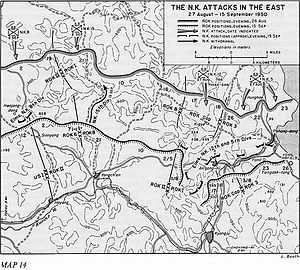

Kyongju corridor

The first North Korean attack struck the UN right flank on the east coast.[29] Although the NK II Corps general attack in the north and east was planned for September 2, the NK 12th Division, now with a strength of 5,000 men, started to move forward from the mountains earlier than planned, from where it had reorganized after its defeat in the Kigye and P'ohang-dong area.[27] The division was low in food supply, weapons, and ammunition, and its men suffered from low morale.[25][30] Facing the NK 12th Division was the ROK Capital Division.[30] At 04:00 on August 27, a North Korean attack overran one company of the ROK 17th Regiment, Capital Division, north of Kigye. This caused the whole regiment to buckle and retreat. Then the ROK 18th Regiment to the east fell back because of its exposed flank. The ROK 17th Regiment lost the town of Kigye in pulling back, and the entire Capital Division fell back 3 miles (4.8 km) to the south side of the Kigye valley.[28][31]

Walker ordered Major General John B. Coulter to observe the ROK troops on the east.[28] Coulter flew to Kyongju, arriving there at 12:00 that day. Walker in the meantime formally appointed Coulter Deputy Commander, Eighth Army, placing him in command of the ROK I Corps which controlled the Capital and 3rd Divisions, the US 21st Infantry Regiment, the 3rd Battalion, US 9th Infantry Regiment, and the 73rd Medium Tank Battalion, less C Company. Coulter designated these units Task Force Jackson and established his headquarters in the same building in Kyongju in which the ROK I Corps commander and the Korean Military Advisory Group (KMAG) officers had their command post.[28]

Coulter was tasked with eliminating the North Korean penetration in the Kigye area and of seizing and organizing the high ground extending from north of Yongch'on to the coast at Wolp'o-ri, about 12 miles (19 km) north of P'ohang-dong. This line passed 10 miles (16 km) north of Kigye.[32] Coulter was to attack as soon as possible with Task Force Jackson to gain the first high ground north of Kigye. The US 21st Infantry Regiment was moving to a position north of Taegu on the morning of August 27, when Walker revoked its orders and instructed it to turn around and proceed as rapidly as possible to Kyongju and report to Coulter.[28] Coulter immediately sent the 3rd Battalion north to An'gang-ni where it went into a position behind the ROK Capital Division.[33]

Coulter's plan to attack on August 28 had to be postponed.[34] Brigadier General Kim Hong Il, the ROK I Corps commander, told him he could not attack, that there were too many casualties and the South Korean were exhausted. The NK 5th Division above P'ohang-dong had begun to press south again and the ROK 3rd Division in front of it began to show signs of pulling back. On the 28th, the KMAG adviser to the ROK 3rd Division and Brigadier General Kim Suk Won clashed over whether the division should retreat or attack.[33] That day, August 28, Walker issued a special statement addressed to the ROK Army, and meant also for the South Korean Minister of Defense, Shin Sung-mo. He called on the ROK troops to hold their lines in the Pusan Perimeter, and implored the rest of the UN troops to defend their ground as firmly as possible, counterattacking as necessary to prevent the North Koreans from consolidating their gains.[35]

At the same time, elements of the NK 5th Division penetrated the ROK 3rd Division southwest of P'ohang-dong. Coulter directed the 21st Infantry to repel this penetration. During the day on August 29, B Company, 21st Infantry, supported by a platoon of tanks of B Company, 73rd Medium Tank Battalion, successfully counterattacked northwest from the southern edge of P'ohang-dong for a distance of 1.5 miles (2.4 km), with ROK troops following. The American units then withdrew to P'ohang-dong. That night the ROK's withdrew, and the next day an American infantry-tank force repeated the action of the day before. The 21st Infantry then took over from the ROK 3rd Division a sector extending north and northwest of P'ohang-dong. Also on August 29, the ROK Capital Division, with American tank and artillery support, recaptured Kigye and held it during the night against North Korean counterattacks, only to lose it again at dawn. American air attacks continued at an increased tempo in the Kigye area.[35]

At the same time, North Korean pressure built up steadily north of P'ohang-dong, where the NK 5th Division fed replacements on to Hill 99 in front of the ROK 23rd Regiment. This hill became almost as notorious as Hill 181 near Yongdok had earlier because of the almost continuous and bloody fighting that occurred there for its control. Although aided by US air strikes and artillery and naval gunfire, the ROK 3rd Division was not able to capture this hill, and suffered many casualties in the effort. On September 2 the US 21st Infantry attacked northwest from P'ohang-dong in an effort to help the South Koreans recapture Hill 99. A platoon of tanks followed the valley road between P'ohang-dong and Hunghae. The regimental commander assigned K Company Hill 99 as its objective. The company was unable to take Hill 99 from the well dug-in North Koreans. At dusk a North Korean penetration occurred along the boundary between the ROK Capital and 3rd Divisions 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Kigye.[36]

The next morning, September 2 at 01:30, the NK 12th Division, executing its part of the coordinated NK II Corps general attack, struck the Capital Division on the high hill masses south of the Kigye valley.[30] This attack threw back the ROK 18th Regiment on the left in the area of Hills 334 and 438, and the ROK 17th Regiment on the right in the area of Hill 445.[32] By dawn of September 3, the North Korean penetration there had reached the vital east-west corridor road 3 miles (4.8 km) east of An'gang-ni. As a result of this gain during the night, the NK 12th Division had advanced 5 miles (8.0 km) and the Capital Division all but collapsed.[36] This forced Coulter to withdraw the 21st Infantry from the line northwest of P'ohang-dong and concentrate it in the vicinity of Kyongju.[37] The 2nd Battalion had joined the regiment on August 31, but Coulter had held it in the task force's reserve at An'gang-ni. That battalion now took up a horseshoe-shaped defense position around the town, with some elements on high ground 2 miles (3.2 km) east where they protected the Kyongju to P'ohang-dong highway. The rest of the regiment closed into an assembly area north of Kyongju. At the same time, Walker started the newly activated ROK 7th Division toward the North Korean penetration. Its ROK 5th Regiment closed at Yongch'on that afternoon, and the ROK 3rd Regiment, less its 1st Battalion, closed at Kyongju in the evening. Walker also authorized Coulter to use the 3rd Battalion, 9th Infantry; the 9th Infantry Regimental Tank Company; and the 15th Field Artillery Battalion as he deemed advisable. These units, held at Yonil Airfield for its defense, had not previously been available for commitment elsewhere.[38]

During the day on September 3, Coulter and the KMAG advisers continued to clash with the ROK 3rd Division commander, who repeatedly attempted to withdraw his troops against their orders.[38] That night, September 3/4, the remainder of the ROK I Corps front collapsed.[31] Three North Korean T-34 tanks overran a battery of ROK artillery and then scattered two battalions of the newly arrived ROK 5th Regiment. Following a mortar preparation, the North Koreans entered An'gang-ni at 0220. An hour later the command post of the Capital Division withdrew from the town and fighting became increasingly confused. American units disengaged and withdrew and by nightfall, North Koreans held the town and began advancing southward along the railroad.[38]

By 12:00 on September 4, North Korean units had established roadblocks along the Kyongju-An'gang-ni road within 3 miles (4.8 km) of Kyongju. A 2 miles (3.2 km) gap existed between the ROK 3rd and Capital Divisions in the P'ohang-dong area.[31] But the big break in the UN line was in the high mountain mass west of the Hyongsan valley and southwest of An'gang-ni. In this area northwest of Kyongju there was an 8 miles (13 km) gap between the Capital Division and the ROK 8th Division to the west. From that direction the North Koreans posed a threat to the railroad and the road net running south through the Kyongju corridor to Pusan. Faced with this big gap on his left flank, Coulter put the US 21st Infantry in the broad valley and on its bordering hills northwest of Kyongju to block any approach from that direction.[39]

The night of September 5/6, events reached a climax inside P'ohang-dong.[40] The ROK division commander, Brigadier General Lee Jun Shik and several members of his senior staff claimed they became sick after their command post was hit with artillery fire. The division withdrew from P'ohang-dong, and on September 6 it was again in North Korean hands. The ROK Army relieved both the ROK I Corps and the ROK 3rd Division commanders.[41] At this time new commanders were appointed for these major commands. Brigadier General Kim Paik Il took command of ROK I Corps, while Capital Division came under command of Colonel Song Yo Ch'an, and ROK 3rd Division came under command of Colonel Lee Jong Ch'an.[30]

Yongch'on

In the high mountains between the Taegu sector on the west and the Kyongju-east coast sector, two North Korean divisions, the 8th and 15th, also prepared an attack south on September 1 to break the supply route between Taegu and P'ohang-dong, which was in the vicinity of Hayang and Yongch'on. This attack would coordinate with the North Korean offensive in the Kigye-P'ohang area. Hayang is 12 miles (19 km), and Yongch'on 20 miles (32 km) east of Taegu. The NK 8th Division was astride the main Andong-Sinnyong-Yongch'on road 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Yongch'on and the NK 15th Division was eastward in the mountains just below Andong, 35 miles (56 km) north of Yongch'on on a poor and mountainous secondary road. The objective of the NK 8th Division was Hayang; the objective of the 15th was Yongch'on, which the division had orders to take at all costs.[42] Opposing the NK 8th Division was the ROK 6th Division; in front of the NK 15th Division stood the ROK 8th Division.[17]

In ten days of fighting the NK 8th Division gained only a few miles (km), and not until September 12 did it have possession of Hwajong-dong, 14 miles (23 km) northwest of Yongch'on. In this time it lost nearly all the 21 new T-34 tanks of the 17th Armored Brigade that were supporting it. Just below Hwajong-dong, mountains close in on the road, with Hill 928 (Hwa-san) on the east and lesser peaks on the west. At this passage of the mountains into the Taegu corridor, the ROK 6th Division decisively defeated the NK 8th Division and practically destroyed it. By September 8 some of the North Korean battalions could muster no more than 20 men.[17][43]

On the next road eastward above Yongch'on, the NK 15th Division launched its attack against the ROK 8th Division on September 2.[17] Although far understrength, with its three regiments reportedly having a total of only 3,600 men, it penetrated in four days to the lateral corridor at Yongch'on. North of the town, one regiment of the ROK 8th Division crumbled when a T-34 tank got behind its lines. Elements of the North Korean division were in and south of Yongch'on by September 6. The North Koreans did not remain in the town, but moved to the hills south and southeast of it overlooking the road between Taegu and P'ohang-dong. On September 7 some of the North Korean troops established a roadblock 3.5 miles (5.6 km) southeast of Yongch'on, and other elements attacked a ROK regiment 1 mile (1.6 km) south of the town. During the day, however, the ROK 5th Regiment of the ROK 7th Division, attacking from the east along the lateral corridor, cleared Yongch'on itself of North Koreans and then went into a defensive position north of the town. But the next day, September 8, additional elements of the NK 15th Division arrived before Yongch'on and recaptured it. That afternoon the ROK 11th Regiment of the ROK 1st Division arrived from the Taegu front and counterattacked the North Koreans in and near the town. This action succeeded in clearing the North Koreans from most of Yongch'on, but some North Koreans still held the railroad station southeast of it.[43] Still others were an unknown distance southeast on the road toward Kyongju.[17]

In the hills southeast and east of Yongch'on, the NK 15th Division encountered very stiff resistance. Its artillery regiment outpaced the North Korean infantry, expended its ammunition, and, without support, was then largely destroyed by ROK counterattack. The North Korean artillery commander was killed in the action. After the ROK 5th and 11th Regiments arrived in the vicinity of Yongch'on to reinforce the demoralized 8th Division, South Korean action against the North Korean units was so intense that the two armies had no chance to regroup for co-ordinating action. On September 9 and 10 ROK units surrounded and virtually destroyed the NK 15th Division southeast of Yongch'on on the hills bordering the Kyongju road. The North Korean division chief of staff, Colonel Kim Yon, was killed there together with many other high-ranking officers. The part played by KMAG officers in rounding up stragglers of the ROK 8th Division and in reorganizing its units was an important factor in the successful outcome of these battles. On September 10, the ROK 8th Division cleared the Yongch'on-Kyongju road of the North Koreans, capturing two tanks, six howitzers, a 76 mm self-propelled gun, several antitank guns, and many small arms.[44]

Advancing north of Yongch'on after the retreating survivors of the NK 15th Division, the ROK 8th Division and the 5th Regiment of the ROK 7th Division encountered almost no resistance. On September 12, elements of the two ROK organizations were 8 miles (13 km) north of the town. On that day they captured four 120 mm mortars, four antitank guns, four artillery pieces, nine trucks, two machine guns, and numerous small arms. ROK forces now also advanced east from Yongch'on and north from Kyongju to close the breach in their lines.[44]

The most critical period of the fighting in the east occurred when the NK 15th Division broke through the ROK 8th Division to Yongch'on. The North Korean division attempted to turn east and southeast and take Task Force Jackson in the rear or on its left flank. But Walker's quick dispatch of the ROK 5th and 11th Regiments from two widely separated sectors of the front to the area of penetration resulted in destroying the force before it could exploit its breakthrough. Walker was commended for his judgment of the reinforcements needed to stem the North Korean attacks in the Kyongju and Yongch'on areas.[44]

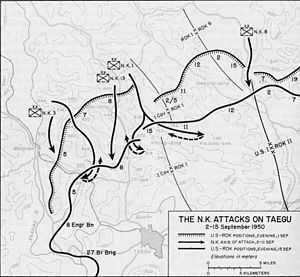

Taegu

Tabu-dong

While four divisions of the NK II Corps attacked south in the P'ohang-dong, Kyongju, and Yongch'on area, the remaining three divisions of the corps—the 3rd, 13th, and 1st—conducted a converging attack on Taegu from the north and northwest.[20] The NK 3rd Division was to attack in the Waegwan area northwest of Taegu, the NK 13th Division down the mountain ridges north of Taegu along and west of the Sangju-Taegu road, and the NK 1st Division along the high mountain ridges just east of the road.[45]

Defending Taegu, the US 1st Cavalry Division had a frontage of approximately 35 miles (56 km). The Divisional Commander Major General Hobart R. Gay outposted the main avenues of entry into his zone and kept his three regiments concentrated behind these outposts.[20] Walker ordered the 1st Cavalry Division to attack north on September 1 in an effort to divert some of the North Korean strength from the US 2nd and 25th Infantry Divisions in the south.[46] Gay's initial decision upon receipt of this order was to attack north up the Sangju road, but his staff and regimental commanders all joined in urging that the attack instead be against Hill 518 in the US 7th Cavalry zone. Only two days before, Hill 518 had been in the ROK 1st Division zone and had been considered a North Korean assembly point. The US 1st Cavalry Division, accordingly, prepared for an attack in the 7th Cavalry sector and for diversionary attacks by two companies of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, on the 7th Cavalry's right flank. This left the 8th Cavalry only one infantry company in reserve. The regiment's 1st Battalion was on the hill mass to the west of the Bowling Alley and north of Tabu-dong; its 2nd Battalion was astride the road.[45]

This planned attack against Hill 518 coincided with the defection of Major Kim Song Jun of the NK 19th Regiment, NK 13th Division. He reported that a full-scale North Korean attack was to begin at dusk that day. The NK 13th Division, he said, had just taken in 4,000 replacements, 2,000 of them without weapons, and was now back to a strength of approximately 9,000 men. Upon receiving this intelligence, Gay alerted all front-line units to be prepared for the attack.[45]

Complying with Eighth Army's order for a spoiling attack against the North Koreans northwest of Taegu, Gay ordered the 7th Cavalry to attack on September 2 and seize Hill 518.[47] Situated north of the lateral Waegwan-Tabu–dong road, and about midway between the two towns, it was a critical terrain feature dominating the road between the two places. After securing Hill 518, the 7th Cavalry attack was to continue on to Hill 314. Air strikes and artillery preparations were to precede the infantry attack.[48]

On the morning of September 2 the US Air Force delivered a 37-minute strike against Hills 518 and 346. The artillery then laid down its concentrations on the hills, and after that the planes came over again with napalm, leaving the heights on fire. Just after 10:00, and immediately after the final napalm strike, the 1st Battalion, US 7th Cavalry, attacked up Hill 518.[48] The heavy air strikes and the artillery preparations had failed to dislodge the North Koreans.[25] From their positions they delivered mortar and machine-gun fire on the climbing infantry, stopping the weak lead elements of the US force short of the crest. In the afternoon the US battalion withdrew from Hill 518 and attacked northeast against Hill 490, from which other North Korean troops had fired in support of the North Koreans on Hill 518.[49] The next day at 12:00, the newly arrived 3rd Battalion resumed the attack against Hill 518 from the south, as did the 1st Battalion the day before, in a column of companies that resolved itself in the end into a column of squads. Again the attack failed. Other attacks failed on September 4. A North Korean forward observer captured on Hill 518 said that 1,200 North Koreans were dug in on the hill and that they had large numbers of mortars and ammunition to hold out.[49]

While these attacks were in progress on its right, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment, on September 4 attacked and captured Hill 303. The next day it had difficulty in holding the hill against counterattacks.[49] By September 4 it had become clear that the NK 3rd Division in front of the 5th and 7th Cavalry Regiments was also attacking, and despite continued air strikes, artillery preparations, and infantry efforts on Hill 518, it was infiltrating large numbers of its troops to the rear of the attacking US forces.[46] That night large North Korean forces came through the gap between the 3rd Battalion on the southern slope of Hill 518 and the 2nd Battalion westward. The North Koreans turned west and occupied Hill 464 in force. By September 5, Hill 464 to the rear of the US 7th Cavalry had more North Koreans on it than Hill 518 to its front.[49] The North Koreans cut the Waegwan to Tabu-dong road east of the regiment so that its communications with other US units now were only to the west.[25] During the day the 7th Cavalry made a limited withdrawal on Hill 518, giving up on capturing the hill.[49]

On the division's right, Tabu-dong was in North Korean hands, on the left Waegwan was a no-man's land, and in the center strong North Korean forces were infiltrating southward from Hill 518.[50] The 7th Cavalry Regiment in the center could no longer use the Waegwan-Tabu-dong lateral supply road behind it, and was in danger of being surrounded.[51] After discussing a withdrawal plan with Walker, on September 5 Gay issued an order for a general withdrawal of the 1st Cavalry Division during the night to shorten the lines and to occupy a better defensive position.[46][51]

Heavy rains fell during the night of September 5/6 and mud slowed all wheeled and tracked vehicles in the withdrawal.[52] The 2nd Battalion disengaged from the North Korean and began its withdrawal at 03:00 on September 6. The North Koreans quickly discovered that the 2nd Battalion was withdrawing and attacked it. In the vicinity of Hills 464 and 380 the battalion discovered at daybreak that it was virtually surrounded by North Koreans.[53] Moving by itself and completely cut off from all other units, G Company, numbering only about 80 men, was hardest hit.[53]

On the division's left, meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry, on Hill 303 came under heavy attack and the battalion commander wanted to withdraw. This battalion suffered heavy casualties before it abandoned Hill 303 on the September 6 to the North Koreans.[53] While G Company was trying to escape from Hill 464, the rest of the 2nd Battalion was cut off at the eastern base of Hill 380, to the south.[53] Later in the day on September 7, the battalion received radio orders to withdraw by any route as soon as possible. It moved southwest into the 5th Cavalry sector.[54]

East of the 2nd Battalion, the North Koreans attacked the 1st Battalion in its new position on September 7 and overran the battalion aid station, killing four and wounding seven men. That night the 1st Battalion was attached to the 5th Cavalry Regiment. The rest of the 7th Cavalry Regiment moved to a point near Taegu in division reserve. During the night of September 7/8 the 5th Cavalry Regiment on division orders withdrew still farther below Waegwan to new defensive positions astride the main Seoul-Taegu highway.[54] The North Korean 3rd Division was still moving reinforcements across the Naktong.[50] Observers sighted barges loaded with troops and artillery pieces crossing the river 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Waegwan on the evening of the 7th. On the 8th the North Korean communiqué claimed the capture of Waegwan.[54]

The next day the situation grew worse for the 1st Cavalry Division. On its left flank, the NK 3rd Division forced the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, to withdraw from Hill 345, 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Waegwan. The North Koreans pressed forward and the 5th Cavalry was immediately locked in hard, seesaw fighting on Hills 203 and 174. The 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, before it left that sector to rejoin its regiment, finally captured the latter hill after four attacks.[54]

Only with difficulty did the 5th Cavalry Regiment hold Hill 203 on September 12. Between midnight and 04:00 on September 13, the North Koreans attacked again and took Hill 203 from E Company, Hill 174 from L Company, and Hill 188 from B and F Companies. In an afternoon counterattack the regiment regained Hill 188 on the south side of the highway, but failed against Hills 203 and 174 on the north side. On the 14th, I Company again attacked Hill 174, which had by now changed hands seven times.[54] In this action the company suffered 82 casualties. Even so, the company held only one side of the hill, the North Korean held the other, and grenade battles between the two continued for another week.[55] The battalions of the 5th Cavalry Regiment were so low in strength at this time that they were not considered combat effective.[56] This seesaw battle continued in full 8 miles (13 km) northwest of Taegu.[57][58]

Ka-san

The 1st Cavalry Division commander, Gay, alerted all of his division's front-line units to be prepared for the attack in the Ka-san sector as well.[25][45][46] ROK 1st Division commander Major General Paik Sun Yup also braced his men for attack.[45]

The attack hit with full force in the "Bowling Alley" area north of Taegu.[59] The attack caught the US 8th Cavalry Regiment unprepared at Sangju. The division was poorly deployed along the road to that town, lacking a reserve force to counterattack effectively. The North Koreans struck the 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, the night of September 2/3 on Hill 448 west of the Bowling Alley and 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Tabu-dong, and overran it.[50] The overrun 2nd Battalion withdrew through the 3rd Battalion which had assembled hastily in a defensive position south of Tabu-dong.[56] During the day, elements of the NK 1st Division forced the 8th Cavalry I&R Platoon and a detachment of South Korean police from the Walled City of Ka-san on the crest of Hill 902, 4 miles (6.4 km) east of Tabu-dong.[60] On September 3, therefore, the UN command, the Eighth Army lost both Tabu-dong and Hill 902, locally called Ka-san, the dominant mountain-top 10 miles (16 km) north of Taegu.[56]

This sudden surge of the North Koreans southward toward Taegu concerned Walker.[25] The Army ordered an ROK battalion from the Taegu Replacement Training Center to a position in the rear of the 8th Cavalry, and the 1st Cavalry Division organized Task Force Allen, to be commanded by Assistant Division Commander Brigadier General Frank A. Allen, Jr.[50][61] It was to be used in combat as an emergency force should the North Koreans break through to the edge of Taegu.[61] Eighth Army countered the North Korean advance down the Tabu-dong road by ordering the 1st Cavalry Division to recapture and defend Hill 902.[61] This hill, 10 miles (16 km) north of Taegu, afforded observation all the way south through Eighth Army positions into the city, and, in North Korean hands, could be used for general intelligence purposes and to direct artillery and mortar fire.[50][61]

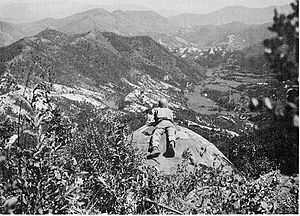

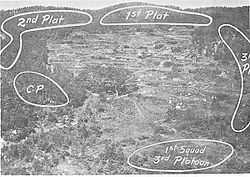

Colonel Raymond D. Palmer,[62] commanding the 8th Cavalry Regiment was ordered to retake the mountain with the help of several support units.[63][64] The next morning, September 4, the force moved to Ka-san[50] and set up an assembly area near the village of Kisong-dong 2 miles (3.2 km) east of the Tabu-dong road. During the afternoon and evening of September 3, the NK 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment, 1st Division, had occupied the summit of Ka-san.[63] The engineer company started its attack up the mountain about noon of September 4, following a trail up a southern spur.[50][65] Less than 1 mile (1.6 km) up the trail, the company came under machine gun fire twice.[65] North Korean mortar fire also struck the company during its climb, but the head of the company arrived at the bowl-shaped summit of Hill 755, the southern arm of the Hill 902 crest.[65] The platoon commander placed the 90 men of his company in position facing in an arc from west to northeast; the 2nd Platoon took the left flank near the stone wall, the 1st Platoon took the center position on a wooded knoll, and the 3rd Platoon the right flank at the edge of a woods. The D Company position was entirely within the area enclosed by the stone wall.[66]

As several squads left the hill on a patrol, North Koreans attacked the main company position behind it. The platoon dropped down off the ridge into a gully on the left. Some of the men in the advanced squad made their way back to US lines, but North Koreans captured most near the bottom of Ka-san on September 10 as they were trying to make their way through the North Korean lines.[66] About 30 minutes after D Company had reached Hill 755, an estimated North Korean battalion launched an attack down the slope running south to Hill 755 from the crest of Hill 902. The company to turned back this attack. That night, North Korean mortar and small arms fire harassed the company and there were several small probing North Korean attacks.[67]

At dawn on September 5 the North Koreans attacked.[64] The engineers repulsed this attack but suffered some casualties. Ammunition was running low and three US C-47 Skytrain aircraft came over the area to make an airdrop. The planes mistakenly dropped their bundles of ammunition and food on the North Korean positions. Immediately after the airdrops, two F-51 Mustang fighter planes came over and attacked D Company, also in error. Soon after this aerial attack, North Korean troops attacked the positions.[67]

Sometime between 10:00 and 11:00, E Company, 8th Cavalry Regiment, arrived on top of Hill 755 and came into D Company's perimeter. North Korean fire, killing several of the porters, turned it back.[67] Shortly after the E Company platoon joined Vandygriff, the North Koreans attacked again unsuccessfully. The American units, out of ammunition, relied on captured North Korean equipment.[68] At 13:30 Gay ordered the 8th Cavalry Regiment to withdraw its men off Ka-san.[69] Gay believed he had insufficient forces to secure and hold it and that the North Koreans had insufficient ammunition to exploit its possession as an observation point for directing artillery and mortar fire.[68] Rain started falling again and heavy fog closed in on the mountain top and severely reduced visibility there. Again the North Koreans attacked as the final units began their withdrawal. When all remaining members of D Company had been assembled, Holley found that the company had suffered 50 percent casualties; 18 men were wounded and 30 were missing in action.[70]

Soldiers of the ROK 1st Division captured a North Korean near Ka-san on September 4 who said that about 800 North Korean soldiers were on Ka-san with three more battalions following them from the north. The engineer company had succeeded only in establishing a perimeter briefly within the North Korean-held area.[70] By evening of September 5, Ka-san was securely in North Korean hands with an estimated five battalions, totaling about 1,500 soldiers, on the mountain and its forward slope. By September 10, 400–500 North Koreans were on the ridge of Ka-San, as observed by a T-6 Mosquito spotter plane.[71] Now, with Ka-san firmly in their possession, the NK 13th and 1st Divisions made ready to press on downhill into Taegu they set up a roadblock which was repulsed the next day.[25][69][71] Even though the 1st Cavalry Division fell back nearly everywhere on September 7, Walker ordered it and the ROK II Corps to attack and seize Hill 902 and Ka-san.[69][71] On the morning of September 8, an estimated 1,000 North Korean soldiers were on Hill 570, 8 miles (13 km) north of Taegu, and Walker decided the continued pressure against the eastern flank of the 1st Cavalry Division sector was the most immediate threat to the UN Forces at Pusan Perimeter. That same day, the 1st Cavalry Division canceled a planned continuation of the attack against Hill 570 by the 3rd Battalion, US 7th Cavalry Regiment, when North Korean forces threatened Hills 314 and 660, south and east of 570.[72]

In the midst of this drive on Taegu, an ammunition shortage became critical for the UN forces.[73] Eighth Army on September 10 reduced the ration of 105 mm howitzer ammunition from 50 to 25 rounds per howitzer per day, except in cases of emergency. Carbine ammunition was also in critical short supply. The 17th Field Artillery Battalion, with the first 8-inch howitzers to arrive in Korea, could not engage in the battle for lack of ammunition.[72]

The NK 1st Division now began moving in the zone of the ROK 1st Division around the right flank of the 1st Cavalry Division.[73] Its 2nd Regiment, with 1,200 men, advanced 6 miles (9.7 km) eastward from the vicinity of Hill 902 to the towering 4,000 feet (1,200 m) high mountain of P'algong-san. It reached the top of P'algong-san about daylight on September 10, and a little later new replacements made a charge toward the ROK positions. The ROK repulsed the charge, killing or wounding about two-thirds of the attacking force.[72]

The US 1st Cavalry Division now had most of its combat units concentrated on its right flank north of Taegu.[73] The 3rd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, attached to the 8th Cavalry Regiment, was behind that regiment on Hills 181 and 182 astride the Tabu-dong road only 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Taegu. The rest of the 7th Cavalry Regiment (the 1st Battalion rejoined the regiment during the day) was in the valley of the Kumho River to the right rear between the North Koreans and the Taegu Airfield, which was situated 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of the city. The US 5th Cavalry Regiment was disposed on the hills astride the Waegwan road 8 miles (13 km) northwest of Taegu. On its left the entire 8th Engineer Combat Battalion was in line as infantry, with the mission of holding a bridge across the Kumho River near its juncture with the Naktong River east of Taegu.[74]

The fighting north of Taegu on September 11 in the vicinity of Hills 660 and 314 was heavy and confused.[73] For a time, the 1st Cavalry Division feared a breakthrough to the blocking position of the 3d Battalion, 7th Cavalry.[75] The rifle companies of the division were now very low in strength.[74] While the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, again vainly attacked Hill 570 on September 11, North Korean soldiers seized the crest of Hill 314 2 miles (3.2 km) southeast of it and that much closer to Taegu.[73] The 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, hurried to the scene from its attacks on Hill 570 and tried to retake the position.[73][74] The 3rd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, command post had to fight off infiltrating North Koreans on September 12 as it issued its attack order and prepared to attack through the 8th Cavalry lines against Hill 314.[74] This attack on the 12th was to be part of a larger American and ROK counterattack against the NK 13th and 1st Divisions in an effort to halt them north of Taegu.[73] The 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, relieved the ROK units on Hill 660, east of Hill 314, and had the mission of securing that hill. Farther east the ROK 1st Division had the mission of attacking from P'algong-san toward Ka-san. The point nearest Taegu occupied by North Korean forces at this time was Hill 314. The NK 13th Division valued its possession and had concentrated about 700 soldiers on it. The North Koreans intended to use Hill 314 in making the next advance on Taegu. From it, observation reached to Taegu and it commanded the lesser hills southward rimming the Taegu bowl.[74] Hill 314 is actually the southern knob of a 500 metres (1,600 ft) hill mass which lies close to the east side of Hill 570 and is separated from that hill mass only by a deep gulch.[73] The southern point rises to 314 metres (1,030 ft) and the ridge line climbs northward from it in a series of knobs. The ridge line is 1 mile (1.6 km) in length, and all sides of the hill mass are very steep.[76]

Lieutenant Colonel James H. Lynch's 3rd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, numbered 535 men on the eve of its attack against Hill 314, less its rear echelons.[73][76] The US troops took the hill and fended off a counterattck.[73][76] Many of the officers in the companies were wounded but refused evacuation and simply continued the attack.[77] The North Korean soldiers on Hill 314 wore American uniforms, helmets, and combat boots. Many of them had M1 rifles and carbines.[50] About 200 North Korean dead were on the hill. Of the other 500 estimated to have been there, most of them had been wounded or were missing.[78] After the capture of Hill 314 on September 12, the situation north of Taegu improved.[50][79] On September 14 the 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, attacked and, supported by fire from Hill 314, gained part of Hill 570 from the NK 19th Regiment, 13th Division.[78]

Across the army boundary on the right, the ROK 1st Division continued its attack northwest and advanced to the edge of Ka-san.[79] The ROK 11th Regiment seized Hill 755 about dark on September 14, and small elements of the ROK 15th Regiment reached the stone ramparts of the Ka-san area at the same time. The ROK and North Korean troops fought during the night and on into the 15th at many points along the high mountain backbone that extends southeast from Ka-san to Hills 755 and 783 and on to P'algong-san. The ROK 1st Division later estimated that approximately 3,000 North Koreans were inside Ka-san's walled perimeter and about 1,500 or 2,000 outside it near the crest.[78] At this time the bulk of the NK 1st Division was gradually withdrawing into Ka-san and its vicinity. Indications were that the NK 13th Division also was withdrawing northward.[79] Aerial observers on the afternoon of September 14 reported that an estimated 500 North Korean troops were moving north from Tabu-dong.[78] While these signs were hopeful, Walker continued to prepare for a final close-in defense of Taegu.[55] As part of this, 14 battalions of South Korean police dug in around the city.[78]

The fighting continued unabated north of Taegu on the 15th.[31][79] The 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, still fought to gain control of Hill 570 on the east side of the Tabu-dong highway. On the other side, the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, attacked Hill 401 where a North Korean force had penetrated in a gap between the 8th and 5th Cavalry Regiments. The fighting on Hill 401 was particularly severe. Both sides had troops on the mountain when night fell.[80]

Naktong Bulge

Second Naktong Bulge

During the North Koreans' September 1 offensive, the US 25th Infantry Division's US 35th Infantry Regiment was heavily engaged in the Battle of Nam River north of Masan. On the 35th Regiment's right flank, just north of the confluence of the Nam River and the Naktong River, was the US 9th Infantry Regiment, US 2nd Infantry Division.[81] There, in the southernmost part of the 2nd Infantry Division zone, the 9th Infantry Regiment held a sector more than 20,000 yards (18,000 m) long, including the bulge area of the Naktong where the First Battle of Naktong Bulge had taken place earlier in August.[60] Each US infantry company on the river line here had a front of 3,000 feet (910 m) to 4,000 feet (1,200 m) and they held only key hills and observation points, as the units were extremely spread out along the wide front.[81]

During the last week of August, US troops on these hills could see minor North Korean activity across the river, which they thought were North Koreans organizing the high ground on the west side of the Naktong against a possible American attack.[25] There were occasional attacks on the 9th Infantry's forward positions, but to the men in the front lines this appeared to be only a standard patrol action.[81] On August 31, the UN forces were alerted to a pending attack when much of the Korean civilian labor force fled the front lines. Intelligence officers reported an attack was coming.[59]

On the west side of the Naktong, North Korean Major General Pak Kyo Sam, commanding the NK 9th Division, issued his operations order to the division on August 28. Its mission in the forthcoming attack was to outflank and destroy the US troops at Naktong Bulge by capturing the Miryang and Samnangjin areas to cut off the US 2nd Division's route of supply and withdrawal between Taegu and Pusan.[17] However, the North Koreans were not aware that the US 2nd Infantry Division had recently replaced the US 24th Infantry Division in positions along the Naktong River. Consequently they expected lighter resistance; the 24th troops were exhausted from months of fighting but the 2nd Division men were fresh and newly arrived in Korea.[81] They had only recently been moved into the line.[17][25] The North Koreans began crossing the Naktong River under cover of darkness at certain points.[59]

The first North Korean crossing at the Paekchin ferry caught a Heavy Mortar Platoon unprepared in the act of setting up its weapons.[82] It also caught most of the D and H Company, 9th Infantry men at the base of Hill 209, .5 miles (0.80 km) from the crossing site. The North Koreans killed or captured many of the troops there.[82][83] The first heavy weapons carrying party was on its way up the hill when the North Korean attack engulfed the men below. It hurried on to the top where the advance group waited and there all hastily dug in on a small perimeter. This group was not attacked during the night.[83]

From 21:30 until shortly after midnight the NK 9th Division crossed the Naktong at a number of places and climbed the hills quietly toward the 9th Infantry river line positions.[83] Then, when the artillery barrage preparation lifted, the North Korean infantry were in position to launch their assaults. These began in the northern part of the regimental sector and quickly spread southward.[82] At each crossing site the North Koreans would overwhelm local UN defenders before building pontoon bridges for their vehicles and armor.[83]

At 02:00, B Company was attacked.[84][85] The hills on both sides of B Company were already under attack as was also Hill 311, a rugged terrain feature a 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the river and the North Koreans' principal immediate objective.[82] On Hill 209 the North Koreans drove B Company from its position, inflicting very heavy casualties on it.[85]

At 03:00, 1 September, the 9th Infantry Regiment ordered its only reserve, E Company, to move west along the Yongsan-Naktong River road and take a blocking position at the pass between Cloverleaf Hill and Obong-ni Ridge, 3 miles (4.8 km) from the river and 6 miles (9.7 km) from Yongsan.[85] This was the critical terrain where so much heavy fighting had taken place in the first battle of the Naktong Bulge.[82] Fighting began at the pass at 02:30.[85] A strong North Korean force surprised and delivered heavy automatic fire at 03:30 from positions astride the road east of the pass.[82] With the critical parts of Cloverleaf Hill and Obong-ni Ridge, the best defensive terrain between Yongsan and the river, the North Koreans controlled the high ground. The US 2nd Infantry Division now had to base its defense of Yongsan on relatively poor defensive terrain, the low hills at the western edge of the town.[85]

North of the 9th Infantry sector of the 2nd Infantry Division front along the Naktong, the US 23rd Infantry Regiment on August 29 had just relieved the 3rd Battalion of the US 38th Infantry Regiment, which in turn had only a few days before relieved the US 21st Infantry Regiment of the US 24th Infantry Division.[84][86] It took over a 16,000 yards (15,000 m) front on the Naktong River without its 3rd Battalion which had been attached to the US 1st Cavalry Division to the north.[82][85] On August 31 the 2nd Division moved E Company south to a reserve position in the 9th Infantry sector.[87]

At 21:00 the first shells of what proved to be a two-hour North Korean artillery and mortar preparation against the American river positions of 2nd Platoon.[84] As the barrage rolled on, North Korean infantry crossed the river and climbed the hills in the darkness under cover of its fire.[82] At 23:00 the barrage lifted and the North Koreans attacked along the battalion outpost line.[87] As the North Korean attack developed during the night, 1st Battalion succeeded in withdrawing a large part of its force, less C Company, just north of Lake U-p'o and the hills there covering the northern road into Changnyong, 3 miles (4.8 km) east of the river and 5 miles (8.0 km) west of the town. B Company lost heavily in this action.[88]

When word of the disaster that had overtaken 1st Battalion reached regimental headquarters, G and F Companies from 2nd Division reserve were sent to help 1st Battalion and the latter on the southern road toward Pugong-ni and C Company.[88] This force was unable to reach C Company, but Lieutenant Colonel Carl C. Jensen collected stragglers from it and seized high ground astride this main approach to Changnyong near Ponch'o-ri above Lake Sanorho, and went into a defensive position there.[82] The US 2nd Division released E Company to the regiment and the next day it joined F Company to build up what became the main defensive position of the 23rd Regiment in front of Changnyong.[88] North Korean troops during the night passed around the right flank of 1st Battalion's northern blocking position and reached the road three miles behind him near the division artillery positions.[82] The 23rd Infantry Headquarters and Service Companies and other miscellaneous regimental units finally stopped this penetration near the regimental command post 5 miles (8.0 km) northwest of Changnyong.[88]

Before the morning of 1 September had passed, reports coming in to US 2nd Division headquarters made it clear that North Koreans had penetrated to the north-south Changnyong-Yongsan road and cut the division in two;[82] the 38th and 23d Infantry Regiments with the bulk of the division artillery in the north were separated from the division headquarters and the 9th Infantry Regiment in the south.[84] Division commander Major General Laurence B. Keiser decided that this situation made it advisable to control and direct the divided division as two special forces.[89] Accordingly, he placed the division artillery commander, Brigadier General Loyal M. Haynes, in command of the northern group. Southward, in the Yongsan area, Keiser placed Brigadier General Joseph S. Bradley, Assistant Division Commander, in charge of the 9th Infantry Regiment, the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, most of the 72nd Tank Battalion, and other miscellaneous units of the division. This southern grouping was known as Task Force Bradley.[88]

All three regiments of the NK 2nd Division—the 4th, 17th, and 6th, in line from north to south—crossed during the night to the east side of the Naktong River into the 23rd Regiment sector. The NK 2nd Division, concentrated in the Sinban-ni area west of the river, had, in effect, attacked straight east across the river and was trying to seize the two avenues of advance into Changnyong above and below Lake U-p'o. On August 31, 1950, Lake U-p'o was a large body of water although in most places very shallow.[90] The massive North Korean attack had made deep penetrations everywhere in the division sector except in the north in the zone of the 38th Infantry.[89] The NK 9th Division had effected major crossings of the Naktong at two principal points against the US 9th Infantry; the NK 2nd Division in the meantime had made three major crossings against the US 23rd Infantry; and the NK 10th Division had begun crossing more troops in the Hill 409 area near Hyongp'ung in the US 38th Infantry sector.[90]

Communication from division and regimental headquarters to nearly all the forward units was broken.[89] As information slowly built up at division headquarters it became apparent that the North Koreans had punched a hole 6 miles (9.7 km) wide and 8 miles (13 km) deep in the middle of the division line and made less severe penetrations elsewhere.[84] The front-line battalions of the US 9th and 23rd Regiments were in various states of disorganization and some companies had virtually disappeared.[89] Keiser hoped he could organize a defense along the Changnyong-Yongsan road east of the Naktong River, and prevent North Korean access to the passes eastward leading to Miryang and Ch'ongdo.[91]

Walker decided that the situation was most critical in the Naktong Bulge area of the US 2nd Division sector.[75] There the North Koreans threatened Miryang and with it the entire Eighth Army position. Walker ordered US Marine Corps Brigadier General Edward Craig, commanding the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, to prepare the Marines to move at once.[92] The Marines made ready to depart for the Naktong Bulge at 13:30.[93]

North of the US 9th Infantry and the battles in the Naktong Bulge and around Yongsan, the US 23rd Infantry Regiment after daylight of September 1 was in a very precarious position.[75] Its 1st Battalion had been driven from the river positions and isolated 3 miles (4.8 km) westward. Approximately 400 North Koreans now overran the regimental command post, compelling Colonel Paul L. Freeman to withdraw it about 600 yards (550 m).[64] There, 5 miles (8.0 km) northwest of Changnyong, the US 23rd Infantry Headquarters and Headquarters Company, miscellaneous regimental units, and regimental staff officers checked the North Koreans in a 3-hour fight.[94]

Still farther northward in the zone of the US 38th Infantry the North Koreans were also active.[64] At 06:00 on September 3, 300 North Koreans launched an attack from Hill 284 against the 38th Regiment command post.[95] This fight continued until September 5. On that day F Company captured Hill 284 killing 150 North Koreans.[64][95]

Meanwhile, during these actions in its rear, the 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry, was cut off 3 miles (4.8 km) west of the nearest friendly units.[95][96] On the morning of September 1, 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry moved in an attack westward from the 23rd Regiment command post near Mosan-ni to open the road to the 1st Battalion. On the second day of the fighting at the pass, the relief force broke through the roadblock with the help of air strikes and artillery and tank fire. The advanced elements of the battalion joined 1st Battalion at 17:00 on September 2. That evening, North Koreans strongly attacked the 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry, on Hill 209 north of the road and opposite 1st Battalion, driving one company from its position.[97]

On September 4, Haynes changed the boundary between the 38th and 23rd Infantry Regiments, giving the northern part of the 23rd's sector to the 38th Infantry, thus releasing 1st Battalion for movement southward to help the 2nd Battalion defend the southern approach to Changnyong.[97] The 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry, about 1,100 men strong when the attack began, was now down to a strength of approximately 600 men. The 23rd Infantry now made plans to concentrate all its troops on the position held by its 2nd Battalion on the Pugong-ni-Changnyong road.[64] The 1st Battalion moved there and took a place on the left flank of the 2nd Battalion. At the same time the regimental command post moved to the rear of this position. In this regimental perimeter, the 23rd Infantry fought a series of hard battles. Simultaneously it had to send combat patrols to its rear to clear infiltrating North Koreans from Changnyong and from its supply road.[97]

The NK 2nd Division made a new effort against the 23rd Infantry's perimeter in the predawn hours of September 8, in an attempt to break through eastward. This attack, launched at 02:30 and heavily supported with artillery, penetrated F Company. It was apparent that unless F Company's position could be restored the entire regimental front would collapse. When all its officers became casualties, First Lieutenant Ralph R. Robinson, adjutant of the 2nd Battalion, assumed command of the company.[97]

The attack tapered off with the coming of daylight, but that night it resumed. The North Koreans struck repeatedly at the defense line. This time they continued the fighting into the daylight hours of 9 September.[97] The Air Force then concentrated strong air support over the regimental perimeter to aid the ground troops.[64] Casualties came to the aid stations from the infantry companies in an almost steady stream during the morning. All available men from Headquarters Company and special units were formed into squads and put into the fight at the most critical points. At one time, the regimental reserve was down to six men. When the attack finally ceased shortly after 12:00 the 23rd Regiment had an estimated combat efficiency of only 38 percent.[98]

This heavy night and day battle cost the NK 2nd Division most of its remaining offensive strength.[64] The medical officer of the NK 17th Regiment, 2nd Division, captured a few days later, said that the division evacuated about 300 men nightly to a hospital in Pugong-ni, and that in the first two weeks of September the 2nd Division lost 1,300 killed and 2,500 wounded in the fighting west of Changnyong. Even though its offensive strength was largely spent by September 9, the division continued to harass rear areas around Changnyong with infiltrating groups as large as companies. Patrols daily had to open the main supply road and clear the town.[98] North Korean and US troops remained locked in combat along the Naktong River for several more days. The North Koreans' offensive capability was largely destroyed, and the US troops resolved to hold their lines barring further attack.[98]

Yongsan

On the morning of September 1 the 1st and 2nd Regiments of the NK 9th Division, in their first offensive of the war, stood only a few miles short of Yongsan after a successful river crossing and penetration of the American line.[31][99] The 3rd Regiment had been left at Inch'on, but division commander Major General Pak Kyo Sam felt the chances of capturing Yongsan were strong.[100] As the NK 9th Division approached Yongsan, its 1st Regiment was on the north and its 2nd Regiment on the south.[99] The division's attached support, consisting of one 76 mm artillery battalion from the NK I Corps, an antiaircraft battalion of artillery, two tank battalions of the NK 16th Armored Brigade, and a battalion of artillery from the NK 4th Division, gave it unusually heavy support.[46][101] Crossing the river behind it came the 4th Division, a greatly weakened organization, far understrength, short of weapons, and made up mostly of untrained replacements.[99] A captured North Korean document referred to this grouping of units that attacked from the Sinban-ni area into the Naktong Bulge as the main force of NK I Corps. Elements of the 9th Division reached the hills just west of Yongsan during the afternoon of September 1.[25][101]

On the morning of September 1, with only the shattered remnants of E Company at hand, the US 9th Infantry Regiment, US 2nd Infantry Division had virtually no troops to defend Yongsan.[99] Division commander Major General Lawrence B. Keiser in this emergency attached the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion to the regiment. The US 72nd Tank Battalion and the 2nd Division Reconnaissance Company also were assigned positions close to Yongsan. The regimental commander planned to place the engineers on the chain of low hills that arched around Yongsan on the northwest.[101][102] Disorganized US forces were ordered to pull back to Yongsan.[101] The road to Miryang came south out of Yongsan, bent around the western tip of this mountain, and then ran eastward along its southern base.[99] In its position, they not only commanded the town but also its exit, the road to Miryang.[89][101] North Koreans had also approached Yongsan from the south.[103] That night North Korean soldiers crossed the low ground around Yongsan and entered the town from the south.[84][104]

US troops attempted to rally and fend off the North Korean attack, but were too disorganized to mount effective resistance.[75][105] By evening the North Koreans had been driven into the hills westward.[102] In the evening, the 2nd Battalion and A Company, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, occupied the first chain of low hills 0.5 miles (0.80 km) beyond Yongsan, the engineers west and the 2nd Battalion northwest of the town.[105] For the time being at least, the North Korean drive toward Miryang had been halted.[106] In this time, the desperately undermanned US units began to be reinforced with Korean Augmentees (KATUSAs.) However, the cultural divide between the KATUSAs and the US troops caused tensions.[107] At 09:35 on September 2, while the North Koreans were attempting to destroy the engineer troops at the southern edge of Yongsan and clear the road to Miryang,[75] Walker attached the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade to the US 2nd Division[92] and ordered a co-ordinated attack by all available elements of the division and the Marines, with the mission of destroying the North Koreans east of the Naktong River in the 2nd Division sector and restoring the river line.[75][105] The Marines were to be released from 2nd Division control as soon as this mission was accomplished.[50][106]

Between 03:00 and 04:30 on September 3, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade moved to forward assembly areas.[108] The 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines assembled north of Yongsan, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines south of it. The 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines established security positions southwest of Yongsan along the approaches into the regimental sector from that direction.[109][110] The Marine attack started at 08:55 on September 3, across the rice paddy land toward North Korean-held high ground 0.5 miles (0.80 km) westward.[111] Air strikes, artillery concentrations, and machine gun and rifle fire of the 1st Battalion now caught North Korean reinforcements in open rice paddies moving up from the second ridge and killed most of them.[94] That night the Marines dug in on a line 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Yongsan. Total Marine casualties for September 3 were 34 killed and 157 wounded. Coordinating its attack with that of the marines, the 9th Infantry advanced abreast of them on the north.[94] The counterattack continued at 08:00 September 4, at first against little opposition.[112] By nightfall the counterattack had gained another 3 miles (4.8 km).[94] That night was quiet until just before dawn. The North Koreans then launched an attack against the 9th Infantry on the right of the marines, the heaviest blow striking G Company.[113] It had begun to rain again and the attack came in the midst of a downpour.[108][114] American artillery fire concentrated in front of the 9th Infantry helped greatly in repelling the North Koreans in this night and day battle.[115]

That morning, September 5, after a 10-minute artillery preparation, the American troops moved out in their third day of counterattack.[116] As the attack progressed, the Marines approached Obong-ni Ridge and the 9th Infantry neared Cloverleaf Hill where they had fought tenaciously during the First Battle of Naktong Bulge the month before.[108] There, at midmorning, on the high ground ahead, they could see North Korean troops digging in. The Marines approached the pass between the two hills and took positions in front of the North Korean-held high ground.[115] At 14:30 approximately 300 North Korean infantry came from the village of Tugok and concealed positions, striking B Company on Hill 125 just north of the road and east of Tugok.[108] Two T-34 tanks surprised and knocked out the two leading Marine M26 Pershing tanks. Since the destroyed Pershing tanks blocked fields of fire, four others withdrew to better positions.[115] Assault teams of B Company and the 1st Battalion with 3.5-inch rocket launchers rushed into action, took the tanks under fire, and destroyed both of them, as well as an armored personnel carrier following behind.[108] The North Korean infantry attack was brutal and inflicted 25 casualties on B Company before reinforcements from A Company and supporting Army artillery and the Marine 81 mm mortars helped repel it.[55][115] September 5 was a day of heavy casualties everywhere on the Pusan Perimeter.[96] Army units had 102 killed, 430 wounded, and 587 missing in action for a total of 1,119 casualties. Marine units had 35 killed, 91 wounded, and none missing in action, for a total of 126 battle casualties. Total American battle casualties for the day were 1,245 men.[115] It is unknown how many North Koreans were killed or wounded on that day, but they likely suffered heavy casualties.[117]

The American counteroffensive of September 3–5 west of Yongsan, according to prisoner statements, resulted in one of the bloodiest debacles of the war for a North Korean division. Even though remnants of the NK 9th Division, supported by the low strength NK 4th Division, still held Obong-ni Ridge, Cloverleaf Hill, and the intervening ground back to the Naktong on September 6, the division's offensive strength had been spent at the end of the American counterattack.[96] The NK 9th and 4th divisions were not able to resume the offensive.[94]

Just after midnight on September 6, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was ordered back to Pusan in order to travel to Japan and merge with other Marine units to form the 1st Marine Division.[96] This was done after a heated disagreement between Walker's command and MacArthur's command. Walker said he could not hold the Pusan Perimeter without the Marines in reserve, while MacArthur said he could not conduct the Inchon landings without the Marines.[55] MacArthur responded by assigning the 17th Infantry Regiment, and later the 65th Infantry Regiment, would be added to Walker's reserves, but Walker did not feel the inexperienced troops would be effective. Walker felt the transition endangered the Perimeter at a time when it was unclear if it would hold.[58][79]

Masan

Haman

On the extreme west flank, in the center of the 25th Division line, Lieutenant Colonel Paul F. Roberts' 2nd Battalion, 24th Infantry, held the crest of the second ridge west of Haman, 1 mile (1.6 km) from the town. From Chungam-ni, in North Korean territory, a secondary road led to Haman along the shoulders of low hills and across rice paddy ground, running east 1 mile (1.6 km) south of the main Chinju-Masan road. It came through Roberts' 2nd Battalion position in a pass 1 mile (1.6 km) west of Haman.[118] Late in the afternoon of August 31, observers with G Company, 24th Infantry, noticed activity 1 mile (1.6 km) in front of their positions. They called in two air strikes that hit this area at dusk. US Artillery sent a large concentration of fire into the area, but the effect of this fire was not known. All US units on the line were alerted for a possible North Korean attack.[119]

That night the North Koreans launched their coordinated offensive against the entire UN force. The NK 6th Division advanced first, hitting F Company on the north side of the pass on the Chungam-ni-Haman road. The ROK troops in the pass left their positions and fell back on G Company south of the pass.[119] The North Koreans captured a 75 mm recoilless rifle in the pass and turned it on American tanks, knocking out two of them. They then overran a section of 82 mm mortars at the east end of the pass.[120] South of the pass, at dawn, First Lieutenant Houston M. McMurray found that only 15 out of 69 men assigned to his platoon remained with him, a mix of US and ROK troops. The North Koreans attacked this position at dawn. They came through an opening in the barbed wire perimeter which was supposed to be covered by a man with a M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle, but he had fled. Throwing grenades and spraying the area with burp gun fire, the North Koreans quickly overran the position.[119] Numerous officers and non-commissioned officers attempted to get the men back into line, but they would not follow these orders. In one instance South Korean troops killed their own company commander when he tried to stop them from escaping.[120]

Shortly after the North Korean attack started most of the 2nd Battalion, 24th Infantry, fled their positions.[121] One company at a time, the battalion was struck with strong attacks all along its front, and with the exception of a few dozen men in each company, each formation quickly crumbled, with most of the troops running back to Haman against the orders of the officers.[122] The North Koreans passed through the crumbling US lines quickly and overran the 2nd Battalion command post, killing several men there and destroying much of the battalion's equipment.[123] With the 2nd Battalion broken, Haman was open to direct North Korean attack. As the North Koreans encircled Haman, Roberts, the 2nd Battalion commander, ordered an officer to take remnants of the battalion and establish a roadblock at the south edge of the town. Although the officer directed a large group of men to accompany him, only eight did so.[124] The 2nd Battalion was no longer an effective fighting force.[121] Pockets of its soldiers remained in place and fought fiercely, but the majority fled upon attack, and the North Koreans were able to move around the uneven resistance. They surrounded Haman as the 2nd Battalion crumbled in disarray.[125]

When the North Korean attack broke through the 2nd Battalion, Regimental commander Colonel Arthur S. Champney ordered the 1st Battalion, about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Haman on the Chindong-ni road, to counterattack and restore the line.[126] Roberts assembled all the 40 men of the disorganized 2nd Battalion he could find to join in this counterattack, which got under way at 0730. Upon contact with the North Koreans, the 1st Battalion broke and fled to the rear.[121] Thus, shortly after daylight the scattered and disorganized men of the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 24th Infantry had fled to the high ground 2 miles (3.2 km) east of Haman.[75] The better part of two regiments of the NK 6th Division poured into and through the Haman gap, now that they had captured the town and held it.[121]

At 14:45 on September 1, division commander Major General William B. Kean ordered an immediate counterattack to restore the 24th Infantry positions.[84] For 30 minutes US Air Force aircraft struck North Korean positions around Haman with bombs, napalm, rockets, and machine gun fire. They also attacked the North Korean-held ridges around the town. Fifteen minutes of concentrated artillery fire followed. Fires spread in Haman. Lieutenant Colonel Gilbert Check's 1st Battalion infantry moved out in attack west at 16:30, reinforced by a platoon of tanks from A Company, 79th Tank Battalion. Eight tanks, mounting infantry, spearheaded the attack into Haman, capturing the city easily, as most of the North Korean troops had abandoned it. North Koreans in force held the ridge on the west side of the town, and their machine gun fire swept every approach. North Korean fire destroyed one tank and the attacking infantry suffered heavy casualties. But Check's battalion pressed the attack and by 18:25 had seized the first long ridge 500 yards (460 m) west of Haman. By 20:00 it had secured half of the old battle position on the higher ridge beyond, 1 mile (1.6 km) west of Haman. Just 200 yards (180 m) short of the crest on the remainder of the ridge, the infantry dug in for the night. It had recaptured Haman and was pushing back to the 24th's old positions.[127]

The North Koreans attacked Haman daily for the next week. Following the repelling of North Korean infiltration on September 7, the North Korean attack on Haman ground to a halt. The North Koreans, racked by logistical and manpower shortages, focused more heavily on their attacks against 24th Infantry positions on Battle Mountain, as well as 35th Infantry positions at the Nam River. 24th Infantry troops at Haman encountered only probing attacks until September 18.[128]

Nam River

Meanwhile the North Korean 7th Division troops committed all of their effort into attacking the US 35th Infantry line.[122] At 23:30 on August 31, a North Korean SU-76 self-propelled high-velocity gun from across the Nam fired shells into the position of G Company, 35th Infantry, overlooking the river.[129] Within a few minutes, North Korean artillery was attacking all front-line rifle companies of the regiment from the Namji-ri bridge west.[16][84] Under cover of this fire a reinforced regiment of the NK 7th Division crossed the Nam River and attacked F and G Companies, 35th Infantry.[130] Other North Korean soldiers crossed the Nam on an underwater bridge in front of the paddy ground north of Komam-ni and near the boundary between the 2nd Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel John L. Wilkins, Jr., holding the river front and Lieutenant Colonel Bernard G. Teeter's 1st Battalion holding the hill line that stretched from the Nam River to Sibidang-san and the Chinju-Masan highway.[129] The 35th Infantry, facing shortages of equipment and reinforcements, was under-equipped but nonetheless prepared for an attack.[131]

In the low ground between these two battalions at the river ferry crossing site, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Fisher had placed 300 ROK National Police, expecting them to hold there long enough to serve as a warning for the rest of the forces.[118] Guns from the flanking hills there could cover the low ground with fire. Back at Komam-ni he held the 3rd Battalion ready for use in counterattack to stop an enemy penetration should it occur.[129] Unexpectedly, the ROK police companies near the ferry scattered at the first North Korean fire.[84] At 00:30, North Korean troops streamed through this hole in the line, some turning left to take G Company in its flank and rear, and others turned right to attack C Company, which was on a spur of ground west of the Komam-ni road.[118] The I&R Platoon and elements of C and D Companies formed a defense line along the dike at the north edge of Komam-ni where US tanks joined them at daybreak. But the North Koreans did not drive for the Komam-ni road fork 4 miles (6.4 km) south of the river as Fisher expected them to; instead, they turned east into the hills behind 2nd Battalion.[129]