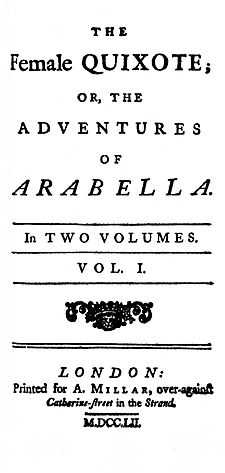

The Female Quixote

The Female Quixote; or, The Adventures of Arabella was a novel written by Charlotte Lennox imitating and parodying the ideas of Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote. Published in 1752, two years after she wrote her first novel, The Life of Harriot Stuart, it was her best known and most celebrated work. It was approved by both Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson, applauded by Samuel Johnson, and used as a model by Jane Austen for her famous work, Northanger Abbey.[1] It has been called a burlesque, "satirical harlequinade", and a depiction of the real power of females.[2] While some dismissed Arabella as a coquette who simply used romance as a tool, Scott Paul Gordon said that she "exercises immense power without any consciousness of doing so".[3] Norma Clarke has ranked it with Clarissa, Tom Jones, and Roderick Random as one of the "defining texts in the development of the novel in the eighteenth century".[4]

Plot

Arabella, the heroine of the novel, was brought up by her widowed father in a remote English castle, where she reads many French romance novels, and imagining them to be historically accurate, expects her life to be equally adventurous and romantic. When her father dies, he declared that she would lose part of her estate if she did not marry her cousin Glanville. After imagining wild fantasies for herself in the country, she visits Bath and London. Glanville is concerned at her mistaken ideas, but continues to love her, while Sir George Bellmour, his friend, attempts to court her in the same chivalric language and high-flown style as in the novels. When she throws herself into Thames in an attempt to flee from horsemen whom she mistakes to be "ravishers" in an imitation of Clélie, she becomes weak and ill. This action might have been inspired by the French satire The Mock-Clielia, in which the heroine "rode at full speed towards the great Canal which she took for the Tyber, and whereinto she threw her self, that she might swim over in imitation of Clelia whom she believed her self to be.[5] The Doctor reasons with her and makes her come to an understanding of the clash of mundane reality and literary illusion, at which she finally accepts Glanville's hand and marries him. In the novel, Arabella often speaks lengthily in defence and about the novels and their heroines.

Critical reception

The critical reception of The Female Quixote was generally favourable: its plot and elevated language, moral vision, and witty commentaries on romance novels were applauded. Fielding's Covent-Garden Journal gave a favourable notice of her book.[6] Dr. Johnson gave a party in honour of her first novel, The Life of Harriot Stuart, in which he served a "magnificent hot apple-pye ... and this he would have stuck with bay-leaves," and "further, he had prepared for her a crown of laurel, with which, but not till he had invoked the muses by some ceremonies of his own invention, he encircled her brows". He was much taken with her work and supportive of The Female Quixote. [7] However, Mrs. Barbauld criticised that it was "rather spun out too much, and not very well wound up." Ronald Paulson remarked that though at first the book seemed to focus "on the heroine's mind", it turned into an "intense psychological scrutiny of Arabella ... replaced by a rather clumsy attempt at the rapid satiric survey of society".[8] Indeed, it is sometimes suggested that the last chapter of the book, in which Arabella comes to understand the difference of reality and the world in the novels through discoursing with "the pious and learned Doctor —", was written by Samuel Johnson. However, the modern critical consensus (affected mainly by the rise in feminist criticism) is that Lennox probably wrote the entire novel.[9]

References

- ↑ Doody, Margaret Anne (1989). Introduction to The Female Quixote. United States: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954024-2.

- ↑ "Chawton House Library: Library and early women's writing – Women writers – Charlotte (Ramsay) Lennox". chawton.org. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ↑ "Female Quixote Bibliography". www4.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ↑ Philippe Sejourne, The Mystery of Charlotte Lennox, First Novelist of Colonial America, Vol. 62 (Aix-En-Provence: Publication Des Annales De La Faculte Des Lettres, 1967).

- ↑ Adrien Thomas Perdou de Subligny, The Mock-Clielia: Being a Comical History of French Gallantries, and Novels, in Imitation of Don Quixote (1678), p. 14

- ↑ Henry Fielding, The Covent-Garden Journal," no. 24, 24 March 1752; see The Covent-Garden Journal," ed. Gerard Edward Jensen, 2 vols. (1915), I: 279-82.

- ↑ Sir John Hawkins, The Life of Samuel Johnson. LL.D. (1787), p. 286

- ↑ Paulson, Satire and the Novel in Eighteenth Century England (1967), p. 277

- ↑ The suggestion was first made by John Mitford (Gentleman's Magazine, N.S. XX, 1843, pp. 132–3). Cf. Miriam Small, Charlotte Ramsay Lennox (1935), pp. 79–82.