The Fabulous World of Jules Verne

| The Fabulous World of Jules Verne | |

|---|---|

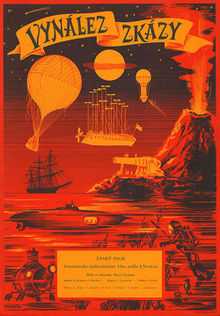

Original Czech film poster | |

| Directed by | Karel Zeman |

| Produced by | Zdeněk Novák |

| Written by |

Karel Zeman František Hrubín Jiří Brdečka Milan Vacha |

| Based on |

Facing the Flag by Jules Verne |

| Starring |

Lubor Tokoš Arnošt Navrátil Miloslav Holub |

| Music by | Zdeněk Liška |

| Cinematography |

Jiří Tarantík Bohuslav Pikhart Antonín Horák |

| Edited by | Zdeněk Stehlík |

| Distributed by |

Ceskoslovensky Statni Film Warner Bros. Pictures (U.S release) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 83 minutes |

| Country | Czechoslovakia |

| Language | Czech |

The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (Czech: Vynález zkázy, literally The Deadly Invention or An Invention for Destruction) is a 1958 Czechoslovak adventure film directed by Karel Zeman. Based on several works by Jules Verne, primarily his 1896 novel Facing the Flag, the film evokes the original illustrations for Verne's works by combining live actors with various forms of animation.[1]

Cast

- Lubor Tokoš as Simon Hart

- Arnošt Navrátil as Professor Roch

- Miloslav Holub as Count Artigas

- František Šlégr as Captain Spade

- Václav Kyzlink as Engineer Serke

- Jana Zatloukalová as Jana

- Otto Šimánek as Man in Train (uncredited)

- Václav Trégl (uncredited)

- František Černý (uncredited)

- Hugh Downs as Introductory Host (US version)

Production

Style

The film has long been appreciated for its unique visual style, which faithfully recreates that of the Victorian line engravings (by Édouard Riou, Léon Benett, and others) featured in the original editions of Verne's novels.[1] According to Karel Zeman's daughter Ludmila Zeman: "As a child, I remember I had all the books with those beautiful engravings. I really can't visualize the story any other way. And my father felt, because he adored Verne, he believed it can only be a good telling if he used the same techniques."[2]

Much of this style was created in-camera, thanks to the production design for the film. Zeman's crew made and used hard rubber paint rollers to add engraving-like hatching to scenery and costumes.[2] The effect was not lost on reviewers: Pauline Kael noted that "there are more stripes, more patterns on the clothing, the decor, and on the image itself than a sane person can easily imagine."[1]

To complete the effect, Zeman and his crew composited the film with various forms of animation. A commentator for Experimental Conversations noted that the end result "must stand alongside [The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari] as one of the great visual and stylistic triumphs of the cinematic medium," and added that "the film combines all manner of tricks and effects - double exposures, painted animation, cut-out animation, stop-motion animation, puppets, miniatures, models, stylised matte-paintings, and who knows what else - with its live-action footage to create a seamless blend of startling, crisp, black-and-white material. The process was dubbed 'Mystimation' [for the later US release], a name which seems perfectly apt for something which really does need to be seen to be believed."[3]

Music

The film's score was written by Zdeněk Liška, a highly regarded film composer known for his skill with musical characterizations and humor, as well as for his innovative use of electronic music techniques.[4] In the mid-twentieth century, he was the foremost Czech composer of fantasy film scores.[5] The score is written in an old-fashioned style complementing the quaintness of the visuals. The main theme, reminiscent of a music box, is scored for harpsichord, accompanied by a chamber ensemble of string instruments and woodwinds. The love theme, apparently based on the song "Tit-willow" from the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera The Mikado, is likewise played by woodwinds and a muted harpsichord.[5] Liška's score also includes various shorter cues, such as a short pathos-filled theme for the sinking of the ship Amelie, keyboard strikes matching the attacks on the giant octopus, and a serene finale for string orchestra.[5] The film's score remains one of Liška's most notable works.[4][5]

Release and reception

Vynález zkázy premiered in Czechoslovakia on 22 August 1958,[6] and was featured at Expo 58 in Brussels, where it won the Grand Prix at the International Film Festival.[7] Over the following year, the film also garnered a Silver Sombrero at the First International Film Festival in Guadalajara, a Czechoslovak Film Critics Award, a Crystal Star from the French Academy of Film, and other awards.[8] In France, André Bazin praised the film in Cahiers du cinéma, and Paul Louis Thirard reviewed it warmly in Positif. The director Alain Resnais named it as one of the ten best films of the year.[9] In 2010, a publication of the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimated Vynález zkázy as the most successful film in the history of Czech cinema.[10]

The film was brought to the United States in 1961 by the American entrepreneur Joseph E. Levine, who had it dubbed into English, christened The Fabulous World of Jules Verne, and released by Warner Bros. Pictures as part of a double feature for children paired with Bimbo the Great.[11] In this release, many of the cast and crew were billed with anglicized names; for example, Lubor Tokoš, Arnošt Navrátil, and Miloslav Holub were credited as Louis Tock, Ernest Navara, and Milo Holl, respectively.[12]

Despite the American niche marketing of the film, it quickly won several high-profile admirers: New York Times critic Howard Thompson found it "fresh, funny and highly imaginative," with "a marvelous eyeful of trick effects."[13] Pauline Kael was similarly glowing, calling the film a "wonderful giddy science fantasy" and adding that Zeman "sustains the Victorian tone, with its delight in the magic of science, that makes Verne seem so playfully archaic."[1] Charles Stinson of the Los Angeles Times began a highly positive review for the film by saying: "The Fabulous World of Jules Verne is precisely that. For once the title writers and the press agents have been found failing to exaggerate. They'd better watch it."[14] Thanks to the American release, the film was nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation in 1962.[15]

In 2011, the science fiction writer John C. Wright identified Vynález zkázy as the first steampunk work and Zeman as the inventor of that genre, commenting that if the film "is not the steam-powered Holy Grail of Steampunkishness, it surely ought to be."[16]

The film was screened by the Museum of Modern Art in December 2012 as part of the exhibition An Auteurist History of Film. MoMA's film curator Charles Silver called the film "a bubbling over […] of unprecedented imagination" with "an undeniably poetic fairy-tale quality."[17] It was screened again in New York City in August 2014 by the Film Society of Lincoln Center, as part of the series "Strange Lands: International Sci-Fi." In The Village Voice, Alan Scherstuhl commented that "The handmade dazzlements still dazzle today … Could it be that old special effects, dependent upon camera tricks and theatrical invention, stir something sympathetic in us that glossy pixels do not, inviting us not just to dream along with the fantasy but also the painstaking creation thereof?"[18]

In 2014, the Karel Zeman Museum in Prague announced that they, in collaboration with České bijáky and Czech TV, had begun a complete digital restoration of the film, planned to be premiered at Expo 2015 in Italy.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kael, Pauline (1991). 5001 Nights at the Movies. New York: Holt. p. 179. ISBN 0-8050-1367-9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Proč Karel Zeman film natočil [Why Zeman Made the Film] (featurette). Prague: Karel Zeman Museum. Nov 6, 2012.

- ↑ Barrett, Alex (Winter 2010). "The Fabulous World of Jules Verne". Experimental Conversations (6). Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gardavský, Čeněk (1965), Contemporary Czechoslovak Composers, Prague: Panton, pp. 280–281

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Larson, Randall D. (1985), Musique Fantastique: A Survey of Film Music in the Fantastic Cinema, Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, p. 216

- ↑ "Vynález zkázy (1958)". kinobox.cz.

- ↑ Pišťanek, Peter (2009-09-17). "Karel Zeman Génius animovaného filmu". SME. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Karel Zeman filmography

- ↑ Bourget, Jean-Loup (June 2000), "Le chaînon manquant: Karel Zeman ressuscité", Positif (472): 98–100

- ↑ Hubálková, Petra (23 September 2010). "Czech film production for children". Czech.cz. Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Czech Republic). Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ "A Strange Introduction to Karel Zeman". TCM Movie Morlocks. TCM. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ American Film Institute (1971), The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States: Feature Films, 1961–1970, Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 318

- ↑ Thompson, Howard (29 June 1961). "Screen: 2 From Abroad: 'World of Jules Verne' and 'Bimbo the Great'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ Stinson, Charles (22 September 1961). "'World of Jules Verne' Archaic Yet Prophetic". Los Angeles Times: A10.

- ↑ "1962 Hugo Awards". The Hugo Awards. World Science Fiction Society. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ↑ Wright, John C. (19 February 2011). "Steampunk is a Diabolical Czech Invention". John C. Wright's Journal. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ Silver, Charles (4 December 2012). "Karel Zeman's The Fabulous World of Jules Verne". Inside/Out. MoMA. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ↑ Scherstuhl, Alan (20 August 2014), "The "Strange Land: International Sci-Fi" Series Boasts Handmade Wonders", The Village Voice, retrieved 27 August 2014

- ↑ Velinger, Jan (25 July 2014), "Karel Zeman Museum offers special programmes in summer", Radio Prague, retrieved 27 August 2014

External links

- The Fabulous World of Jules Verne at the Internet Movie Database

- The Fabulous World of Jules Verne at AllMovie

- Thesis on Zdeněk Liška's music for the film (Czech)

- John Landis on The Fabulous World of Jules Verne at Trailers From Hell

| ||||||||||