The Diary of Lady Murasaki

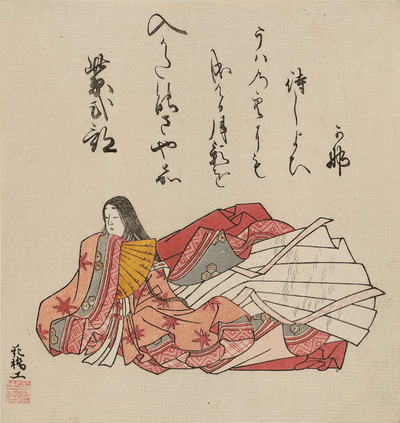

The Diary of Lady Murasaki (紫式部日記 Murasaki Shikibu Nikki) is the title of fragments of a diary written by the 11th century Japanese Heian era lady-in-waiting and writer Murasaki Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genji. Probably written between 1008 and 1010, the largest portion of the diary is about the birth of Empress Shōshi's (Akiko) children.

Murasaki muses about life at the imperial court in shorter vignettes, describing interactions among imperial ladies-in-waiting and the other women court writers, such as Izumi Shikibu, Akazome Emon and Sei Shōnagon. The work was written in kana, then a newly developed writing system for vernacular Japanese. Unlike modern diaries or journals, 10th-century Heian diaries emphasize important events, often ignoring mundane day-to-day life, and fail to follow a strict chronological order. The work includes vignettes, waka poems, and a section written in an epistolary fashion in the form of a long letter.

A Japanese picture scroll, the Murasaki Shikibu Diary Emaki was produced during the Kamakura period in the 13th century.

Diary

The diary consists of three parts: anecdotes in the form of vignettes; the lengthy descriptions of the birth of Empress Shōshi's (Akiko)'s eldest son, Prince Atsuhira; and a section written in an epistolary format as a letter.[2] Murasaki describes court life with an emphasis on events surrounding Shōshi's childbirth.[3]

Set at the imperial court in Kyoto, the work opens with several short vignettes. The first words are: "As autumn advances, the Tsuchimikado mansion looks unutterably beautiful. Every branch on every tree by the lake and each tuft of grass on the banks of the stream takes on its own particular color, which is then intensified by the evening light."[4] In the third vignette she describes an early morning exchange of waka poems with Fujiwara no Michinaga. The vignettes are followed by successively longer passages, detailing Empress Shōshi, her removal from the palace before giving birth, the celebrations surrounding her pregnancy and childbirth, and the rites celebrating the successful delivery of a male heir. The birth descriptions include specific readings of sutras and other Buddhist rituals.[5]

Towards the end of the work, Murasaki reveals her dissatisfaction with court life.[6] She writes about feelings and emotions, the helplessness she feels at court, the sense of inadequacy in regards to her rank compared to higher-ranked Fujiwara clan relatives and courtiers, and the pervasive feelings of loss and loneliness after her husband's death. In doing so, she adds a sense of self to the diary entries.[7]

Murasaki Includes autobiographical snippets before entering imperial service,[2] such as the anecdote about her brother's childhood Chinese lessons:

When my brother Nobunori ... was a boy my father was very anxious to make a good Chinese scholar of him, and often came himself to hear Nobunori read his lessons. On these occasions I was always present, and so quick was I at picking up the language that I was soon able to prompt my brother whenever he got stuck. At this my father used to sigh and say to me: 'If only you were a boy how proud and happy I should be'.[8]

Historical background

Three noteworthy diaries were written by ladies-in-waiting at Emperor Ichijō's imperial court: Murasaki's diary, Sei Shōnagon's The Pillow Book and Izumi Shikibu's diary (Izumi Shikibu Nikki).[9] During the peak of the Heian period in the late 10th to early 11th centuries, Japan underwent a transition away from Chinese influences as a unique national culture emerged, which was particularly evident in women's writing.[10][11] Haruo Shirane explains that during this period waka poetry (as used in the diaries) "became integral to the everyday life of the aristocracy, functioning as a form of elevated dialogue and the primary means of communication between the sexes". As a result, during that period, female aristocratic writers at court set a foundation for "subsequent court literature".[9]

Murasaki Shikibu

Murasaki's diary covers a discrete period, most likely from 1008 to 1010. Only short and fragmentary pieces of the diary survive and its importance lies, in part, in the revelations of the author, about whom not much is known. Most of the known biographical facts about her come from the diary (Murasaki Shikibu nikki) and from her c. 1014 short poetry collection, the Murasaki Shikibu shū (or Poetic Memoirs).[12]

Murasaki was born into a minor branch of the Fujiwara clan; her father was a scholar of Chinese literature who educated his son as well as his daughter in classical Chinese, unusual for the period. She was married and had a daughter; in about c. 1001 her husband, Fujiwara no Nobonori, died during an outbreak of plague. Deeply saddened, she began writing Tale of the Genji shortly thereafter.[13] Around 1006 she entered imperial service to Empress Shōshi, at Michinaga's request and probably based on her reputation as a writer.[14] The diary was almost certainly written after she entered imperial service.[13]

Murasaki's given name is unknown. Women were usually identified by their rank or that of a husband or another close male relative. Shikibu was her father's rank at the Ministry of Ceremonials (Shikibu-shō); her court nickname Murasaki is from a character in the Tale of the Genji.[13]

Fujiwara dynasty

Donald Keene believes the reality of Heian court life Murasaki describes in the diary is the antithesis to what she imagined in her romantic novel, The Tale of Genji, and that the novel's hero, the "shining prince" Genji, contrasts sharply with Michinaga's crassness.[15] Murasaki describes incidents in which he embarrasses his wife, Rinshi, and his daughter with his drunken behavior. Furthermore, he may have indulged in flagrant flirtations with Murasaki, causing embarrassment. Scholars are unsure whether the two were intimate.[16]

.jpg)

The sections of the diary devoted to and describing the birth of Shōshi's son were almost certainly written as tribute to Michinaga,[12] but Murasaki reveals him to be overly controlling.[15] The birth was an event of enormous importance to Michinaga, who nine years earlier brought his daughter to court as concubine to Emperor Ichijō; her quick ascendence to Empress, and status as mother to the heir consolidated Michinaga's power.[3]

Shōshi moved out of the imperial palace when she became pregnant because of the taboo against childbirth in the palace. Prince Atsuhira was born at the Tsuchimikado mansion where Michinaga took the dominated the child's father and attending priests. After the child's birth Michinaga visited the infant twice daily, whereas the Emperor made only a single very short imperial visit, described in great detail.[15][17] Murasaki chronicled each of Michinaga's ceremonial visits, as well as the lavish ceremony held 16 days after the infant's birth. She chronicled the ladies-in-waiting attire in detail: "Saemon no Naishi .... was wearing a plain yellow-green jacket, a train shaded darker at the hem, and a sash and waistbands with raised embroidery in orange and white checked silk".[18]

A serious and studious young woman who expected decorum from her ladies-in-waiting—often difficult at a fractious court—Shōshi decided to learn to read Chinese and asked Murasaki teach her, an unconventional request at a time when Chinese was seen as the "male language", the language of government and religion. Women used Japanese kana for reading and writing. But Shōshi wished to read the then popular ballads of 9th-century Chinese poet Bai Juyi. The Chinese lessons were conducted in secret with Murasaki explaining: "Since the summer before last, very secretly, in odd moments when there happened to be no one about, I have been reading with Her Majesty the two books of "Songs." There has of course been no question of formal lessons; Her Majesty has merely picked up a little here and there, as she felt inclined. All the same, I have thought it best to say nothing about the matter to anybody".[19]

Court life

Murasaki documents the weather and the changing of seasons, and the less pleasant aspects of court life such as inebriated courtiers who frequently seduced the ladies-in-waiting. The diary includes anecdotes about drunken revelries and courtly scandals concerning women who, because of behavior or age, were forced to leave imperial service; she, additionally, documented her own concerns about aging and the overwhelming loneliness she often suffered. Murasaki suggests that the court women with whom she lived were weak-willed, uneducated, and inexperienced with men.[6][16]

Murasaki appears to have been unhappy and lonely at court. She complained about courtiers and princes who were frequently drunk and behaved badly. In one incident court poet Fujiwara no Kintō joined a group of women at a banquet and asked whether Murasaki was in attendance—alluding to the character in The Tale of Genji. Murasaki told him that none of the novel's characters lived at court, which she thought tawdry and unpleasant and unlike the court she created in her novel. She left the dinner, later writing, "Counsellor Takai ... started pulling at Lady Hyōbu's robes and singing dreadful songs, but His Excellency said nothing. I realized that it was bound to be a terribly drunken affair this evening, so ... Lady Saishō and I decided to retire."[20] According to Japanese scholar Donald Keene, male courtiers at the Imperial court were "drunken men who make obscene jokes and paw at women".[21]

Although the women lived in semi-seclusion in curtained areas or screened spaces, privacy was non-existent for them. Men were allowed to intrude on the women's privacy at any time.[22] Murasaki describes an incident when early one morning, as she woke, Michinaga entered sleeping cubicle: "I can see the garden from my room", she wrote. "The air is misty; the dew is still on the leaves. The Lord Prime Minister is walking there .... He peeps in over my screen! His noble appearance embarrasses us and I am ashamed of my morning (not yet painted and powdered face)."[23]

After the Imperial palace burned down in 1005, during Murasaki's tenure at court she lived at one or another of Michinaga's mansions, the Biwa mansion in the Fujiwara quarter of Kyoto, the Tsuchimikado mansion, or Ichijo's mansion, close to the palace grounds. Ladies-in-waiting had to sleep on thin mats rolled out on bare wood floors; interior spaces had few boundaries with a room often created by curtaining off a space. The dwellings were slightly raised and opened to the Japanese garden, affording little privacy. Richard Bowring explains how vulnerable the women were to men watching them: "A man standing outside in the garden looking in .... his eyes would have been roughly level with the skirts of the woman inside."[24]

During winter the houses were cold and drafty with few braziers, requiring the women to dress in layered clothing for warmth.[22] Murasaki writes in detail about the then fashionable kimonos and multi-layered court clothing.[25] The combination of layers became of almost ritual fascination to the women. Court attire for Heian era court women consisted of six or seven garments, with some garments layered as many as five or six times. The lined silk robes, uchigi, involved matching or combining colors of the linings and the garment itself to create a distinctive impression.[22] In one passage she writes about two women whose color combinations were lacking, and of the significance of making a mistake at courtly functions: "That day all the women had done their utmost to dress well, but .... two of them showed a want of taste when it came to the color combinations at their sleeves ... [in] full view of the courtiers and senior nobles."[26] The combinations of colors in a woman's clothing required attention and were important because they marked stylistic aesthetics.[25]

Murasaki became withdrawn and lonely, and was perhaps considered stupid, shy or both.[27] She writes of herself: "Do they really look on me as such a dull thing, I wonder? But I am what I am .... [Shōshi] too has often remarked that she thought I was not the kind of person with whom one could ever relax .... I am perversely stand-offish; if only I can avoid putting off those for whom I have genuine respect."[28] The benefit of being withdrawn seems to have been that she had time to write while living in a crowded court.[27]

Ladies-in-waiting

The diary includes descriptions of other ladies-in-waiting, most notably of Sei Shōnagon who was in service to Shōshi's rival and co-empress, Empress Teishi (Sadako). The two empresses competed to bring educated women to their respective courts and encouraged rivalry among the women writers. Shōnagon probably left court five years before Murasaki's arrival, after Empress Teishi's death in 1006, and two might not have met, yet Murasaki is disparaging of her:

Sei Shōnagon's most marked characteristic is her extraordinary self-satisfaction. But examine the pretentious compositions in Chinese script which she scatters so liberally over the Court, and you will find them to be .... blunders. Her chief pleasure consists in shocking people .... She was once a person of great taste and refinement; but now she can no longer restrain herself from indulging, even under the most inappropriate circumstances....[29]

Murasaki is also critical of the two other women writers at Shōshi's court: the poet Izumi Shikibu and Akazome Emon, who authored a monogatari.[30] Of Izumi's writing and poetry, Murasaki says: "Izumi Shikibu is an amusing letter-writer; but there is something not very satisfactory about her. She has a gift for dashing off informal compositions in a careless running-hand; but in poetry she needs either an interesting subject or some classic model to imitate. Indeed it does not seem to me that in herself she is really a poet at all.[31]

The diary and The Tale of Genji

Murasaki's The Tale of Genji is barely mentioned in the diary. She writes the Emperor had the story read to him, and that colored papers and calligraphers had been selected for transcriptions of the manuscript – done by court women. In one anecdote she tells of Michinaga sneaking into her room to help himself to a copy of the manuscript.[32] There are parallels between the later chapters of Genji and the diary. A scene mentioned in the diary, that of the splendid imperial procession of Ichijo's visit to Michinaga's mansion in 1008,

According to Genji scholar Shirane, the scene in the diary which describes Ichijo's imperial procession to Michinaga's mansion in 1008, "corresponds almost image for image" to an imperial procession in "Chapter 33 (Wisteria Leaves)" of The Tale of Genji.[33] Shirane believes the similarities in the two works suggest that some portions of Genji may have been written during the period Murasaki wrote the diary.[34]

Style and genre

The development in the 9th century of kana, a Japanese writing script and syllabary, opened the way for writing in the vernacular. Chinese continued as the language of government but women, who were usually not taught Chinese, were encouraged to read and write in Japanese. Initially used for writing waka court poetry, by the 10th century works of prose written in kana became more common as women turned to the new script for literary forms such as monogatari and diaries (nikki),[35][36] as imperial ladies-in-waiting began to write diaries.[10] As a result, written Japanese was to a degree developed by women who used the language as a form of self-expression and, as Japanese literature scholar Richard Bowring says, women undertook the process of building "a flexible written style out of a language that has only previously existed in a spoken form". He does, however, explain that the diaries of the period failed make a full transition from a spoken to a written form of the language.[37]

The genre of diary writing popular at the time, known as Nikki Bungaku, is more of an autobiographical memoir than a diary in the modern sense, according to Japanese scholar Helen McCullough. The format typically included poetry in the form of waka,[38] meant to convey information to the readers, as seen in Murasaki's descriptions of court ceremonies.[39] The author of a Heian-era nikki would decide what to include, expand, or exclude. Time was treated in a similar manner; a nikki might present long entries for a single event while other events were omitted. The nikki was considered a form of literature, often not written by the subject, almost always written in third-person, and sometimes included elements of fiction or history.[39] These diaries are a repository of knowledge about the Heian Imperial court, considered highly important in Japanese literature, although many have not survived in a complete state.[15]

Few if any dates are included in the diary and little is written about Murasaki's working habits. Donald Keene says the work should not be compared to a modern "writer's notebook". Instead Murasaki recounts public events combined with self-reflections—an important aspect of the work—bringing a human aspect lacking in official accounts written by historians.[40] According to Keene, the author is revealed as a woman with great perception and self-awareness, yet who is withdrawn with few friends. She is unflinching in her criticism of aristocratic courtiers, seeing beyond superficial facades to their inner core, a quality he says is beneficial for a novelist but less useful in the closed society she inhabited.[41]

Bowring's study of the diary, with comparisons to previous scholarship, leads him to believe it has three distinct styles. The first is a chronicles of events, which would normally have been written in Chinese during this period. The second is a self-reflective analysis, which he says is the best example of self-analytic reflection from the period. Murasaki's mastery of this type of style, at that time quite rare in Japanese, shows the degree to which she aided the development of written Japanese in overcoming the limits of an inflexible language and writing system. The third is the epistolary style, a newly developed trend. Bowring considers this the weakest portion of the work, because she appears unable to break free of the rhythms of spoken language.[42] He explains that spoken language has a specific rhythm and assumes the presence of others, is often ungrammatical, relying on "eye contact, shared experiences and particular relationships [to] provide a background which allows speech to be at times fragmentary and even allusive". Written language must compensate for "the gap between the producer and receiver of the message".[37]

In 1920, Annie Shepley Omori and Kochi Doi published Diaries of Court Ladies of Old Japan; this book combined a translation of Murasaki's diary with that of Izumi Shikibu (The Izumi Shikibu nikki) and of the Sarashina nikki. Their translation had an introduction by Amy Lowell. A more recent English translation was published by Richard Bowring in 1982.[43]

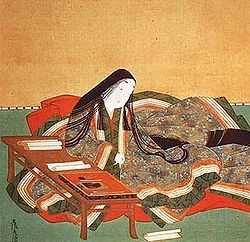

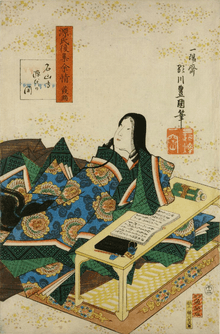

Emakimono handscroll

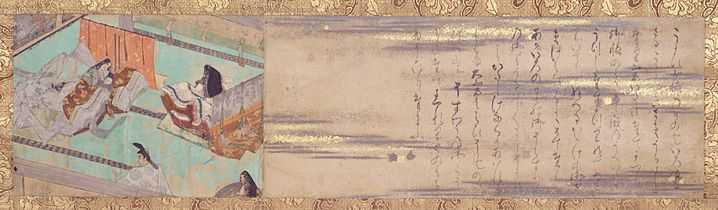

In the 13th century a handscroll of the diary was produced, The Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Emaki. The scroll, meant to be read from left to right, consists of calligraphy illustrated with paintings. Writing in "The House-bound Heart", Japanese scholar Penelope Mason explains that in an emakimono or emaki a narrative reaches its full potential through the combination of the writer's and the painter's art. About 20 percent of the scroll has survived; based on the existing fragments, the images would have closely followed the text of the diary.[44]

_2.jpg)

The illustrations in the emaki follow the late-Heian and early Kamakura period convention of Hikime kagibana (line-eye and hook-nose) in which individual facial expressions are omitted. Also typical of the period is the style of fukimuki yatai (blown off roof) depictions of interiors which seem to be visualized from above looking downward into a space. According to Mason, the interior scenes of human figures are juxtaposed against empty exterior gardens; the characters are "house-bound".[45]

In the diary Murasaki writes of love, hate and loneliness, feelings which make the illustrations, according to Mason, of the "finest extant examples of prose-poetry narrative illustrations from the period".[46] Mason finds the illustration of two young courtiers opening the lattice blinds to enter the women's quarters particularly poignant, because Murasaki tries to hold the lattice shut against their advances. The image shows that the architecture and the men who keep her away from the freedom of the garden to the right.[47]

The scroll was discovered in 1920 in a five segment piece, by Morikawa Kanichirō (森川勘一郎). The Gotoh Museum holds segments one, two and four; the Tokyo National Museum holds the third segment; the fifth remains in a private collection. The portion of the emakimono held at the Gotoh museum have been designated as National Treasures of Japan.[48]

Gallery

-

Detail of the Murasaki Shikibu Diary Ekotoba (紫式部日記絵詞). Handscroll (Emakimono), color on paper. Fujita Art Museum, Osaka, Japan. The scroll has been designated as a National Treasure of Japan.

-

_6.jpg)

Evening of Kankō 5, 11th month, 1st day (December 1, 1008): "Ika-no-iwai" of the Imperial Prince. Drunk, disarranged, and disordered Heian courtiers seen here joking and flirting with ladies-in-waiting. Various facial expressions and attitudes give a lifelike impression.

-

_1.jpg)

Leaf from the diary with calligraphy attributed to Kujō Yoshitsune, held at Gotoh Museum.

-

Fragment of the emaki showing, on the left, an illustration of Shoshi with her newborn son, and on the right the text written in calligraphy.

References

Citations

- ↑ "Detached segment of The Diary of Lady Murasaki, emaki". Emuseum.jp

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Keene (1999), 40–41

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bowring (2005), xv

- ↑ Murasaki Shikibu (Bowring translation, 2005), 3

- ↑ Bowring (2005), xl - xli

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Keene (1999), 44

- ↑ Mason (1980), 30

- ↑ Waley, vii

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Shirane (2008), 113

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Henshall (1999), 24–25

- ↑ Bowring (2005), xii

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Shirane (1987), 215

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Tyler, Royall. "Murasaki Shikibu: Brief Life of a Legendary Novelist: c. 973 – c. 1014". (May, 2002) Harvard Magazine. Retrieved August 21, 2011

- ↑ Shirane (2008), 293

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Keene (1999), 42–44

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Ury (2003), 175–188

- ↑ Bowring (2005), xxiv-xxv

- ↑ qtd in Mulhern (1991), 86

- ↑ Waley (1960), ix-x

- ↑ qtd in Keene (1999), 45

- ↑ Keene (1999), 44–45

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Bowring (2005), xxvii

- ↑ Shikibu, 127

- ↑ Bowring (2005), xxv-xxvii

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Bowring (2005), xxviii

- ↑ Lady Murasaki, 65

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Keene (1999), 46

- ↑ qtd. in Keene (1999), 46

- ↑ Waley (1960), xiii

- ↑ Mulhern (1994), 156

- ↑ Waley (1960), xii

- ↑ Keene (1999), 46–47

- ↑ Shirane (1987), 221

- ↑ Shirane (1987), 36

- ↑ Shirane (2008), 2, 113–114

- ↑ Mason (2004), 109

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Bowring (2005), xviii

- ↑ Waka is always 31 syllables with a measures of 5/7 or 7/5 syllables. In the diary, Murasaki used the so-called short form consisting of a measure of 5/7/5/7/7 syllables. See Bowring, xix

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 McCullough (1990), 15–16

- ↑ Keene (1999), 41–42

- ↑ Keene (1999), 45

- ↑ Bowring (2005), xviii - xix

- ↑ Ury (1983), 175

- ↑ Mason (1980), 24

- ↑ Mason (1980), 22-24

- ↑ Mason (1980), 29

- ↑ Mason (1980), 32-33

- ↑ Gotoh Museum (in Japanese)

Sources

- Bowring, Richard John (ed). "Introduction". in The Diary of Lady Murasaki. (2005). London: Penguin. ISBN 9780140435764

- Frédéric, Louis. Japan Encyclopedia. (2005). Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP. ISBN 0-674-01753-6

- Henshall, Kenneth G. A History of Japan. (1999). New York: St. Martin's. ISBN 0-312-21986-5

- Keene, Donald. Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest times to the Late Sixteenth Century. (1999). New York: Columbia UP. ISBN 0-231-11441-9

- Keene, Donald. Travelers of a Hundred Ages: The Japanese as revealed through 1000 years of diaries. (1999). New York: Columbia UP. ISBN 0-231-11437-0

- Lady Murasaki. The Diary of Lady Murasaki. (2005). London: Penguin. ISBN 9780140435764

- Lowell, Amy. "Introduction". in Diaries of Court Ladies of Old Japan. Translated by Kochi Doi and Annie Sheley Omori. (1920) Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Mason, Penelope. (2004). History of Japanese Art. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-117601-0

- Mason, Penelope. "The House-Bound Heart. The Prose-Poetry Genre of Japanese Narrative Illustration". Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Spring, 1980), pp. 21–43

- McCullough, Helen. Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology. (1990). Stanford CA: Stanford UP. ISBN 0-8047-1960-8

- Mulhern, Chieko Irie. Japanese Women Writers: a Bio-critical Sourcebook. (1994). Westport CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25486-4

- Mulhern, Chieko Irie. Heroic with Grace: Legendary Women of Japan. (1991). Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-87332-527-3

- Reschauer, Edwin. Japan: The Story of a Nation. (1999). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-557074-2

- Shikibu, Murasaki. "Pages from Murasaki Shikbu's Diary". in The Life of Ancient Japan. Singer, Kurt (ed). (2002). Japan Library. ISBN 1-903350-01-8

- Shirane, Haruo. The Bridge of Dreams: A Poetics of "The Tale of Genji". (1987). Stanford CA: Stanford UP. ISBN 0-8047-1719-2

- Shirane, Haruo. Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600. (2008). New York: Columbia UP. ISBN 978-0-231-13697-6

- The Japan Book: A Comprehensive Pocket Guide. (2004). New York: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2847-1

- Ury, Marian. The Real Murasaki. Monumenta Nipponica. (Summer 1983). Vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 175–189.

- Waley, Arthur. "Introduction". in Shikibu, Murasaki, The Tale of Genji: A Novel in Six Parts. translated by Arthur Waley. (1960). New York: Modern Library.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||