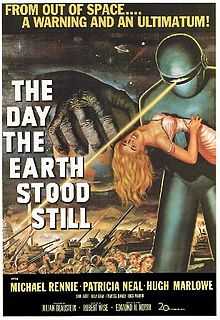

The Day the Earth Stood Still

| The Day the Earth Stood Still | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Robert Wise |

| Produced by | Julian Blaustein |

| Screenplay by | Edmund H. North |

| Based on |

Farewell to the Master by Harry Bates |

| Starring |

Michael Rennie Patricia Neal Hugh Marlowe Sam Jaffe |

| Music by | Bernard Herrmann |

| Cinematography | Leo Tover |

| Edited by | William H. Reynolds |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $995,000[1] |

| Box office | $1,850,000 (US theatrical rentals)[2] |

The Day the Earth Stood Still (aka Farewell to the Master and Journey to the World) is a 1951 American black-and-white science fiction film from 20th Century Fox, produced by Julian Blaustein, directed by Robert Wise, and starring Michael Rennie, Patricia Neal, Hugh Marlowe and Sam Jaffe. The Day the Earth Stood Still was written by Edmund H. North, based on the 1940 science fiction short story "Farewell to the Master" by Harry Bates.[3] The notable score was composed by Bernard Herrmann.[4]

In The Day the Earth Stood Still, humanoid alien visitor named Klaatu comes to Earth, accompanied by a powerful eight-foot tall robot, Gort, to deliver an important message that will affect the entire human race.[5]

Plot

When a flying saucer lands in Washington, D.C., the U.S. Army quickly encircles the spaceship. A humanoid (Michael Rennie) emerges, announcing that he has come in peace. When he advances, however, he unexpectedly opens a small cylindrical device and is shot by a nervous soldier. A tall robot emerges from the saucer and disintegrates all of the soldiers' weapons using an energy ray. The alien orders Gort, the robot, to stop, then explains that the now-broken device was simply a gift for the President, which would have enabled him "to study life on the other planets".

The wounded alien is taken to Walter Reed Hospital, where he reveals his name: Klaatu. He uses a salve to quickly heal his wound. Meanwhile, the military attempts to enter the spaceship, but finds it impenetrable; Gort stands outside the ship, silent and unmoving.

Klaatu tells the President's secretary, Mr. Harley (Frank Conroy), that he has come with a message that must be revealed to all the world's leaders simultaneously. Harley tells him that such a meeting in the current political climate is impossible. Klaatu suggests that he be allowed to go among humans to better understand their "unreasoning suspicions and attitudes." Harley rejects the proposal and leaves Klaatu under guard.

Klaatu escapes and lodges at a boarding house as "Mr. Carpenter" (the name on the dry cleaner's tag on the suit he "borrowed"). Among the residents are young widow Helen Benson (Patricia Neal) and her son Bobby (Billy Gray). The next morning, Klaatu listens to his fellow boarders' speculations about the alien's purpose.

While Helen and her boyfriend Tom Stephens (Hugh Marlowe) go out, Klaatu babysits Bobby. The boy takes Klaatu on a tour of the city, including a visit to his father's grave in Arlington National Cemetery; Klaatu learns that most of those buried there were killed in wars. The two view the heavily guarded saucer and visit the Lincoln Memorial. Klaatu asks Bobby who the greatest person living is; Bobby suggests Professor Barnhardt (Sam Jaffe), who lives in the city. Bobby takes Klaatu to Barnhardt's home, but the professor is absent. Klaatu adds a mathematical equation to a problem on Barnhardt's blackboard and leaves his contact information with the suspicious housekeeper.

Later, government agents escort Klaatu to see Barnhardt. Klaatu warns the professor that the people of the other planets have become concerned for their safety after humans developed atomic power. Klaatu declares that, if his message goes unheeded, "Earth will be eliminated." Barnhardt agrees to gather scientists at Klaatu's saucer, suggesting that Klaatu give a demonstration of his power. Klaatu returns to his spaceship the next evening, unaware that Bobby has followed him. Bobby sees Gort knock out two guards and "Mr. Carpenter" enter the spaceship.

Bobby tells Helen and Tom what he saw, but they do not believe him until Tom takes a diamond found in Klaatu's room to a jeweller, who informs him it is "unlike any other on Earth." Klaatu finds Helen at her workplace. They take an empty service elevator which stops precisely at noon. Klaatu reveals his true identity and asks for her help. He has neutralized all electricity everywhere except where human safety would be compromised, such as hospitals and aircraft in flight.

After the blackout ends, the manhunt for Klaatu intensifies. When Tom informs the military of his suspicions, Helen breaks up with him. Helen and Klaatu take a taxi to Barnhardt's home. En route, he tells her that should anything happen to him, she must go to Gort and say these words: "Klaatu barada nikto". After being spotted, Klaatu makes a break for it, but is gunned-down. Helen then heads to the saucer. Gort awakens, disintegrates the two army night guards, and advances on her. When Helen utters the three words, the robot carries her into the spaceship, then retrieves Klaatu's body. Gort revives Klaatu, but he explains to Helen that this is only temporary, that the power of life and death is "reserved for the Almighty Spirit".

Klaatu and Helen emerge from the saucer after Barnhardt's scientists have assembled. Klaatu declares that the people of Earth have a choice. They can join the other planets in peace, but should they threaten to extend their violence into space, "this Earth of yours will be reduced to a burned-out cinder. [...] We will be waiting for your answer". Klaatu and Gort then depart in their spaceship.

Cast

- Michael Rennie as Klaatu

- Patricia Neal as Helen Benson

- Billy Gray as Bobby Benson

- Hugh Marlowe as Tom Stephens

- Sam Jaffe as Professor Jacob Barnhardt

- Frances Bavier as Mrs. Barley

- Lock Martin as Gort

- Frank Conroy as Mr. Harley

- Tyler McVey as Brady (uncredited)

Cast notes

Well-known broadcast journalists of their time, H. V. Kaltenborn, Elmer Davis, Drew Pearson, and Gabriel Heatter, appeared and/or were heard as themselves in cameo roles.

Spencer Tracy and Claude Rains were originally considered for the part of Klaatu.[6][7]

Metaphors

In a 1995 interview, producer Julian Blaustein explained that Joseph Breen, the film censor installed by the Motion Picture Association of America at the Twentieth Century Fox studios, balked at the portrayal of Klaatu's resurrection and limitless power.[6] At the behest of the MPAA, a line was inserted into the film; when Helen asks Klaatu whether Gort has unlimited power over life and death, Klaatu explains that he has only been revived temporarily and "that power is reserved to the Almighty Spirit."[6][8] Of the elements that he added to Klaatu's character, screenwriter Edmund North said, "It was my private little joke. I never discussed this angle with Blaustein or Wise because I didn't want it expressed. I had originally hoped that the Christ comparison would be subliminal."[9]

That the question even came up in an interview is proof enough that such comparisons did not remain subliminal, but they are subtle enough that it is not immediately obvious to all viewers which elements were intended to compare Klaatu to Christ.[10] He was sent to Earth to provide humans with another chance. When Klaatu escapes from the hospital, he steals the clothing of a "Maj. Carpenter," carpentry being the profession Jesus learned from his father Joseph. He presents himself as John Carpenter, the same initials as Jesus Christ. His message is misunderstood, and he is killed. At the end of the film, Klaatu rises from the dead and ascends into the night sky. Other parallels include his apprehension by authorities at night, his befriending of children, his having wisdom and knowledge far beyond any human being, and people being given a sign of his power.[11]

Production

Development

Producer Julian Blaustein set out to make a film under the working titles of Farewell to the Master and Journey to the World that illustrated the fear and suspicion that characterized the early Cold War and Atomic Age. He reviewed more than 200 science fiction short stories and novels in search of a storyline that could be used, since this film genre was well suited for a metaphorical discussion of such grave issues. Studio head Darryl F. Zanuck gave the go-ahead for this project, and Blaustein hired Edmund North to write the screenplay based on elements from Harry Bates's 1940 short story "Farewell to the Master". The revised final screenplay was completed on February 21, 1951. Science fiction writer Raymond F. Jones worked as an uncredited adviser.[12]

Pre-production

The set was designed by Thomas Little and Claude Carpenter. They collaborated with the noted architect Frank Lloyd Wright for the design of the spacecraft. Paul Laffoley has suggested that the futuristic interior was inspired by Wright's Johnson Wax Headquarters, completed in 1936. Laffoley quotes Wright and his attempt in designing the exterior: "... to imitate an experimental substance that I have heard about which acts like living tissue. If cut, the rift would appear to heal like a wound, leaving a continuous surface with no scar."[13]

Filming

Principal outdoor photography for The Day the Earth Stood Still was shot on the 20th Century Fox sound stages and on its studio back lot (now located in Century City, California), with a second unit shooting background plates and other scenes in Washington D.C. and at Fort George G. Meade in Maryland. The shooting schedule was from April 3 to May 23, 1951. The primary actors never traveled to Washington for the making of the film. Robert Wise indicated in the DVD commentary that the War Department refused participation in the movie based on a reading of the script. The military equipment shown came from the Virginia Army National Guard, although one of the tanks bears the "Brave Rifles" insignia of the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, then stationed at Ft. Meade.[14]

The robot Gort, who serves Klaatu, was played by Lock Martin, who worked as an usher at Grauman's Chinese Theater and stood seven feet tall. Not used to being in such a confining, heat-inducing costume, he worked carefully when wearing the two demanding, metallic-looking, stitched-up-the-front or -back, prop suits needed for creating the illusion on screen of a seamless Gort. Wise decided that Martin's on-screen shooting time would be limited to half hour intervals, so Martin, with his generally weak constitution, would face no more than minor discomfort. These segments, in turn, were then edited together into film's final print.[15]

In a commentary track on DVD, interviewed by fellow director Nicholas Meyer, the director Robert Wise stated that he wanted the film to appear as realistic and believable as possible, in order to drive home the motion picture's core message against armed conflict in the real world. Also mentioned in the DVD's documentary interview was the original title for the movie, "The Day the World Stops." Blaustein said his aim with the film was to promote a "strong United Nations."[16]

Herrmann's score

The music score was composed by Bernard Herrmann in August 1951, and was his first score after he moved from New York to Hollywood. Herrmann chose unusual instrumentation for the film: violin, cello, and bass (all three electric), two theremin electronic instruments (played by Dr. Samuel Hoffman and Paul Shure), two Hammond organs, a large studio electric organ, three vibraphones, two glockenspiels, marimba, tam-tam, 2 bass drums, 3 sets of timpani, two pianos, celesta, two harps, 1 horn, three trumpets, three trombones, and four tubas.[17] Herrmann's notable advances in film scoring included Unison organs, tubas, piano, and bass drum, staggered tritone movement, and glissando in theremins, as well as exploitation of the dissonance between D and E-flat and experimentation with unusual overdubbing and tape-reversal techniques.

Music and soundtrack

| The Day the Earth Stood Still | |

|---|---|

| |

| Film score by Bernard Herrmann | |

| Released | 1993 |

| Recorded | August, 1951 |

| Genre | Soundtracks, Film score |

| Length | 35:33 |

| Label | 20th Century Fox |

| Producer | Nick Redman |

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

20th Century Fox later reused the Bernard Herrmann title theme in the original pilot episode of Irwin Allen's 1965 TV series Lost in Space; the music was also used extensively in Allen's Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea series episode, “The Indestructible Man.” Danny Elfman noted The Day the Earth Stood Still 's score inspired his interest in film composing, and made him a fan of Herrmann.[18]

| Track listing | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length | ||||||||

| 1. | "Twentieth Century Fox Fanfare" | 0:12 | ||||||||

| 2. | "Prelude / Outer Space/Radar" | 3:45 | ||||||||

| 3. | "Danger" | 0:24 | ||||||||

| 4. | "Klaatu" | 2:15 | ||||||||

| 5. | "Gort / The Visor / The Telescope" | 2:23 | ||||||||

| 6. | "Escape" | 0:55 | ||||||||

| 7. | "Solar Diamonds" | 1:04 | ||||||||

| 8. | "Arlington" | 1:08 | ||||||||

| 9. | "Lincoln Memorial" | 1:27 | ||||||||

| 10. | "Nocturne / The Flashlight / The Robot / Space Control" | 5:58 | ||||||||

| 11. | "The Elevator / Magnetic Pull / The Study / The Conference / The Jewelry Store" | 4:32 | ||||||||

| 12. | "Panic" | 0:42 | ||||||||

| 13. | "The Glowing / Alone / Gort's Rage / Nikto / The Captive / Terror" | 5:11 | ||||||||

| 14. | "The Prison" | 1:42 | ||||||||

| 15. | "Rebirth" | 1:38 | ||||||||

| 16. | "Departure" | 0:52 | ||||||||

| 17. | "Farewell" | 0:32 | ||||||||

| 18. | "Finale" | 0:30 | ||||||||

Reception

Critical response

The Day the Earth Stood Still was well received by critics and is widely regarded as one of the best films of 1951.[19][20][21][22]

The Day the Earth Stood Still was moderately successful when released, accruing US$1,850,000 in distributors' domestic (U.S. and Canada) rentals, making it the year's 52nd biggest earner.[23] [Note 1] Variety praised the film's documentary style, and the Los Angeles Times praised its seriousness, though it also found "certain subversive elements."[16] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called it "tepid entertainment."[24]

The Day the Earth Stood Still earned more plaudits overseas: the Hollywood Foreign Press Association gave the filmmakers a special Golden Globe Award for "promoting international understanding." Bernard Herrmann's score also received a nomination at the Golden Globes.[25] The French magazine Cahiers du cinéma was also impressed, with Pierre Kast calling it "almost literally stunning" and praising its "moral relativism."[16]

The Day the Earth Stood Still is ranked seventh in Arthur C. Clarke's list of the best science-fiction films of all time, just above Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, which Clarke himself co-wrote.

The Day the Earth Stood Still holds a 94% "Certified Fresh" rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes.[26]

Legacy

In 1995 The Day the Earth Stood Still was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[27][28]

The Day the Earth Stood Still also received recognition from the American Film Institute. In 2001, it was ranked number 82 on 100 Years...100 Thrills, a list of America's most heart-pounding films.[29] It placed number 67 on a similar list 100 Years...100 Cheers, a list of America's most inspiring films.[30] In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its "10 Top 10" — the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres — after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. The Day the Earth Stood Still was acknowledged as the fifth best film in the science fiction genre.[31] The film was also on the ballot for AFI's other lists including 100 Years...100 Movies,[32] the tenth anniversary list,[33] 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains for Klaatu in the heroes category,[34] 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes for the famous line "Gort! Klaatu barada nikto!",[35] and AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores.[36] In 2004, the film was selected by The New York Times as one of The Best 1000 Movies Ever Made.[37]

Lou Cannon and Colin Powell believed the film inspired Ronald Reagan to discuss uniting against an alien invasion when meeting Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985. Two years later, Reagan told the United Nations, "I occasionally think how quickly our differences worldwide would vanish if we were facing an alien threat from outside this world".[16]

Klaatu barada nikto

Since the release of the film, the phrase "Klaatu barada nikto" has appeared repeatedly in fiction and in popular culture. The Robot Hall of Fame described it as "one of the most famous commands in science fiction",[38] while Frederick S. Clarke of Cinefantastique called it "the most famous phrase ever spoken by an extraterrestrial".[39]

Edmund H. North, who wrote The Day the Earth Stood Still, also created the alien language used in the film, including the iconic phrase "Klaatu barada nikto". The official spelling for the phrase comes directly from the script (as shown in the image to the left) and provides insight as to its proper pronunciation.

No translation was given in the film. Philosophy professor Aeon J. Skoble speculates the famous phrase is a "safe-word" that is part of a fail-safe feature used during the diplomatic missions such as the one Klaatu and Gort make to Earth. With the use of the safe-word, Gort's deadly force can be deactivated in the event the robot is mistakenly triggered into a defensive posture. Skoble observes that the theme has evolved into a "staple of science fiction that the machines charged with protecting us from ourselves will misuse or abuse their power".[40] In this interpretation the phrase apparently tells Gort that Klaatu considers escalation unnecessary.

Fantastic Films magazine explored the meaning of "Klaatu barada nikto" in a 1978 article titled The Language of Klaatu. The article, written by Tauna Le Marbe, who is listed as their "Alien Linguistics Editor", attempts to translate all the alien words Klaatu used throughout the film.[41] In the article the literal translation for Klaatu barada nikto was "Stop Barbarism (I have) death, bind" and the free translation was "I die, repair me, do not retaliate."[41]

The documentary Decoding "Klaatu Barada Nikto": Science Fiction as Metaphor examined the phrase "Klaatu barada nikto" with some of the people involved with The Day the Earth Stood Still. Robert Wise, director of the film, related a story he had with Edmund North saying North told him, "Well, it's just something I kind of cooked up. I thought it sounded good".[42] Billy Gray, who played Bobby Benson in the film, said that he thought that the message was coming from Klaatu and that, "barada nikto must mean ... save Earth".[43] Florence Blaustein, widow of the producer Julian Blaustein, said North had to pass a street called Baroda every day going to work and said, "I think that's how that was born."[44] Film historian Steven Jay Rubin recalled an interview he had with North when he asked the question, "What is the direct translation of Klaatu barada nikto, and Edmund North said to me 'There's hope for earth, if the scientists can be reached.'"[45]

Mozilla Firefox features an Easter egg that involves the phrase; when typing in "about:robots" into the address bar, the words "Gort! Klaatu barada nikto!" appears in the tab display. Other robot-related references on the page include nods to Isaac Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics, the tears in rain soliloquy from the film Blade Runner, two lines from The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, a quote from the character Bender from Futurama, and a tagline from Battlestar Galactica.[46] Klaatu, Barada, and Nikto are the names of three minor characters among the personnel on Jabba The Hutt's sail barge (featured in Return of the Jedi). Sam Raimi used the three words in The Army of Darkness, in a scene where a wise man tells Ash, played by Bruce Campbell, to say "Klaatu barada nikto", so he could take the book safely.

Professor Barnhardt's blackboard problem

The blackboard problem seen in the professor's office is a real set of equations describing the three-body problem fundamental to space travel.[Note 2] Hence this dialog:

Professor Barnhardt: "Have you tested this theory?"

Klaatu: [subtle change in expression] "Um.. I find it works well enough to get me from one planet to another."

Adaptations

The film was dramatized as a radio play on January 4, 1954 for the Lux Radio Theater; Michael Rennie reprised his lead role as Klaatu with actress Jean Peters as Helen Benson. This production was later re-broadcast on the Hollywood Radio Theater, the re-titled Lux Radio Theater, which aired on the Armed Forces Radio Service.[48]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Rentals" refers to the distributor/studio's share of the box office gross, which, according to Gebert, is roughly half of the money generated by ticket sales.[23]

- ↑ Actor Sam Jaffe, who played Professor Barnhardt, had an engineering degree and taught mathematics before turning to acting.[47]

Citations

- ↑ Solomon 1989, p. 246.

- ↑ "The Top Box Office Hits of 1951." Variety, January 2, 1952.

- ↑ Bates, Harry. "Farewell to the Master (full text)." Astounding Stories, October 1940.

- ↑ Gianos 1998 p. 23.

- ↑ Bradbury, Ray. "The Day the Earth Stood Still II: The Evening of the Second Day." scifiscripts.com, March 3, 1981.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Making the Earth Stand Still LaserDisc (Fox Video; 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment): Julian Blaustein, Robert Wise, Patricia Neal, Billy Gray." IMDb, 1995. Retrieved: 1 February 2015.

- ↑ "Cult Movies Showcase 'The Day the Earth Stood Still'." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ Shermer 2001, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Matthews 2007, p. 54.

- ↑ Holloway and Beck 2005, p. 135.

- ↑ Haspel, Paul. "Future Shock on the National Mall." Journal of Popular Film & Television, Vol. 34, Issue 2, Summer 2006, pp. 62–71. ISSN 01956051.

- ↑ "DVD: 'The Day the Earth Stood Still' Shooting Script." Still Galleries, [Fox Video 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment]. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ Laffoley, Paul. "Disco Volante (the Flying Saucer)." laffoleyarchive.com, 1998. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Original Print information: 'The Day the Earth Stood Still'." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ Warren 1982, p. 621.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Hoberman, J. "The Cold War sci-fi parable that fell to earth." The New York Times, September 31, 2008.

- ↑ Wrobel, Bill. "Score analysis." filmscorerundowns.net. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Oscar Roundtable: The composers." The Hollywood Reporter, December 15, 2008.

- ↑ "The Greatest Films of 1951." AMC Filmsite.org. Retrieved: May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "The Best Movies of 1951 by rank." Films101.com, May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "The Best Films of 1951: A Definitive List." Amazon.com, May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Most Popular Feature Films Released in 1951." IMDb.com, May 23, 2010.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Gebert 1996, p. 156.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley. "The Screen in review: Emissary from planet visits Mayfair Theatre in 'Day the Earth Stood Still'." The New York Times, September 19, 1951.

- ↑ "'The Day the Earth Stood Still'; Award Wins and Nominations." IMDb.com. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "'The Day the Earth Stood Still' Movie Reviews, Pictures." Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Films Selected to The National Film Registry, Library of Congress 1989-2009." loc.gov. Retrieved: June 19, 2010.

- ↑ "'The Day the Earth Stood Still': Award Wins and Nominations." IMDb.com. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills." AFI.com. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers." AFI.com. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10." AFI.com Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies: Official Ballot." AFI.com. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary): Official Ballot." AFI. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains: The 400 Nominated Characters." AFI.com. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes: Official Ballot." AFI.com. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores: Official Ballot." AFI.com. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

- ↑ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made." The New York Times, April 29, 2003.

- ↑ "2006 Inductees: Gort." The Robot Hall of Fame (Carnegie Mellon University), 2006. The Day the Earth Stood Still

- ↑ Clarke, Frederick S. Cinefantastique, 1970, p. 2.

- ↑ Skoble 2007, p. 91.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Le Marbe, Tauna. "The Language of Klaatu." Fantastic Films, Issue 1, April 1978.

- ↑ "DVD: Decoding "Klaatu Barada Nikto": Science Fiction as Metaphor|time = 0:14:05." Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, December 2, 2008.

- ↑ "DVD: Decoding "Klaatu Barada Nikto": Science Fiction as Metaphor|time = 0:14:20." Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, December 2, 2008.

- ↑ "DVD: Decoding "Klaatu Barada Nikto": Science Fiction as Metaphor| time = 0:14:47." Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, December 2, 2008.

- ↑ "DVD: Decoding "Klaatu Barada Nikto": Science Fiction as Metaphor|time = 0:14:55." Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, December 2, 2008.

- ↑ "About:robots - Firefox 3 Secret!" Firefox Facts, April 8, 2008.

- ↑ Flint, Peter B. "Sam Jaffe, a character actor on stage and film, dies at 93." The New York Times, March 25, 1984.

- ↑ "Notes: 'The Day the Earth Stood Still'." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: February 1, 2015.

Bibliography

- Gebert, Michael. The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards (listing of 'Box Office (Domestic Rentals)' for 1951, taken from Variety magazine). New York: St. Martin's Paperbacks, 1996. ISBN 0-668-05308-9.

- Gianos, Phillip L. Politics and Politicians in American Film. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998. ISBN 0-275-96071-4.

- Holloway, David and John Beck. American Visual Cultures. London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005. ISBN 0-8264-6485-8.

- Matthews, Melvin E.. Hostile Aliens, Hollywood and Today's News: 1950s Science Fiction Films and 9/11. New York: Algora Publishing, 2007. ISBN 0-87586-497-X.

- Shermer, Michael. The Borderlands of Science: Where Sense Meets Nonsense. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-19-514326-4.

- Skoble, Aeon J. "Technology and Ethics in The Day the Earth Stood Still." in Sanders, Steven M. The Philosophy of Science Fiction Film. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2007. ISBN 0-8131-2472-7.

- Solomon, Aubrey. Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching The Skies Vol I: 1950 - 1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1982. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951 film). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Day the Earth Stood Still |

- The Day the Earth Stood Still at the Internet Movie Database

- The Day the Earth Stood Still at the TCM Movie Database

- The Day the Earth Stood Still at AllMovie

- The Day the Earth Stood Still at Box Office Mojo

- The Day the Earth Stood Still at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Day the Earth Stood Still at the Internet Movie Script Database

- The Day the Earth Stood Still on Lux Radio Theater: January 4, 1954

| ||||||||||

| ||||||