The Conchologist's First Book

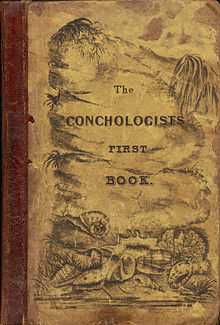

Cover for the first edition | |

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Scientific textbook |

| Publisher | Haswell, Barrington, and Haswell |

Publication date | 1839 |

| Media type | |

The Conchologist's First Book (sometimes subtitled with Or, A System of Testaceous Malacology) is an illustrated textbook on conchology issued in 1839, 1840, and 1845. The book was originally printed under Edgar Allan Poe's name. Poe never claimed, however, that he was the author.[1][2] Poe's condensed version was based on the textbook by Thomas Wyatt, an English author and lecturer.[3] Wyatt wrote the original, longer textbook, Manual of Conchology, upon which Poe based his shorter, condensed version. Poe was the editor or compiler of the work.

Background

Poe originally wrote just the preface and introduction but, for $50, Poe lent his name on the title page of the book, published in Philadelphia by Haswell, Barrington, and Haswell.[3] Poe also edited, arranged, compiled, and made translations. Poe was one of the most important editors in the U.S. at the time. This odd arrangement was to avoid copyright problems with the original edition of Wyatt's book, Manual of Conchology, previously published by Harper & Brothers. Wyatt's book contained multiple illustrations of shells and carried the cover price of $8, a price too high for both beginners and advanced students of conchology. Wyatt intended a cheaper, concise edition to be used in schools with a price of $1.50. Harper's, however, did not want to produce a second edition that would compete with sales of the first.[4] Wyatt had said, "Poe needed money very sorely at the time," and so Poe allowed the use of his name to popularize the book.[5]

Poe made some significant changes to Wyatt's original text. Poe edited, compiled, translated, and organized the textbook into an inexpensive and condensed version intended for use in classrooms. Poe wrote the preface, the introduction, translated the French text by Georges Cuvier into English, worked on the accounts of the animals, constructed a new classification or taxonomy scheme, and organized the book. So Poe made translations of the scientific descriptions by the French naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier, although he was uncredited on the title page.

The new edition sold out within two months and was used in schools as had been hoped, though Poe received no royalties for its sales.[4] It was the only volume by Poe to go into a second edition in the United States during his lifetime.[6] The edition, nonetheless, caused some criticism in later years not only of copyright problems but of plagiarism.[7] In 1844, Poe tried to publish more of his work with Harper's (which had also printed his novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket) but was informed by a friend, "They have complaints against you... grounded on certain movements of yours."[8]

Poe himself explained the book:

I wrote it in conjunction with Professor Thomas Wyatt, and Professor McMultrie... my name being put to the work, as best known and most likely to aid its circulation. I wrote the Preface and Introduction, and translated from Cuvier, the accounts of the animals, etc. All School-books are necessarily made in a similar way."[1]

Poe denied the charge of plagiarism and wrote that he would sue over the allegation: "This charge is infamous, and I shall prosecute for it, as soon as I settle my accounts with the 'Mirror.'"[9] Moreover, Poe had knowledge and a background in conchology based on his acquaintance and association with Dr. Edmund Ravenel, a "eminent conchologist", who had resided on Sullivan's Island during Poe's army service.[10]

Wyatt's book, in turn, took much material from British naturalist Thomas Brown without attribution. Brown's book, The Conchologist's Textbook, had been published in Glasgow, Scotland in 1837.[11] Brown himself based his text on the previous work of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Linnaeus. Brown noted on his title page that his book was "embracing the arrangements of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Linnaeus". In other words, Brown himself could be accused of "plagiarizing" his textbook from Lamarck and Linnaeus.

In his personal copy of the 1839 first edition, Poe made annotations and corrections. He penciled in as the last sentence to the preface an acknowledgment to Thomas Brown: "Also to Mr. T. Brown upon whose excelent [sic] book he has very largely drawn". The second edition of the book, however, did not incorporate Poe's acknowledgment of Brown.

Significance and response

There was much controversy over this book, but Poe never claimed or implied that he wrote or was the author, emphasizing that he edited and arranged a student textbook.[12] Poe was, in fact, the editor, compiler, organizer, and translator, of the book. Poe used his skills as an editor and his knowledge of French to help simplify the book into an inexpensive, condensed format. In the preface, for example, Poe went to great lengths to explain the term conchology. In "Poe's Greatest Hit", American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould showed how Poe made significant contributions to the text by simplifying, organizing, and condensing the text, Manual of Conchology, and, more importantly, by translating Cuvier's passages into English (Gould, Stephen Jay, "Poe's Greatest Hit". Natural History, CII, No. 7, July 1993, pp. 10–19.; also contained in Gould's book Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History. New York: Harmony Books, 1995, Chapter 14.).[13][14] Poe contributed in popularizing and simplifying a subject that otherwise was too esoteric. In this respect, Poe made significant contributions in popularizing science in the United States.[15]

Gould noted that Poe, who was fluent in French, analyzed and translated French naturalist Georges Cuvier's scientific classification scheme. Poe changed the organization of Wyatt's original book. Wyatt had arranged the animals by the shapes of their shells. Poe, however, regarded that mode of classification as too simplistic and superficial. Poe created a much broader classification system by analyzing the derivation of the term conchology, the scientific study of mollusk shells: "The Greek conchylion from which it is derived, he says, embraces both the animal and [its] shell." In fact, Poe constructed a superior system of classification, according to Gould. So while Poe biographers disparage Poe as being "boring, pedantic, and hair-splitting", Poe actually made meaningful and important contributions to the book, and to biological taxonomy, in creating a new and more complex system of classification for mollusks. In other words, according to Gould, Poe did not just put his name on the book, but made significant and meaningful contributions and changes to the text, which was intended as an abridged textbook or primer, not as an original work.[16]

On the title page of the first edition in 1839, it states that the book consists of "A System of Testaceous Malacology Arranged expressly for the use of Schools ... By Edgar A. Poe." This is an accurate description of Poe's role in the production of the book. Poe "arranged" the material, edited, organized, and assembled the material. Moreover, Poe wrote: "The title-page acknowledges that the animals are given 'according to Cuvier'."[2] A second edition appeared in 1840 with Poe's name on the title page. An 1845 edition, however, appeared without Poe's name on it. The controversy and confusion is largely a semantic one. If Poe is credited as the editor, compiler, organizer, translator, and "arranger" of the material, then there is no controversy. The controversy was used largely to slander and libel Poe and to destroy his reputation and credibility during his lifetime. When all the facts and circumstances are analyzed and examined, however, as Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould did, Poe's role in the production of the book can be more accurately determined and assessed.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. p. 275-7. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Thomas, Dwight. “Poe in Philadelphia, 1838-1844: A Documentary Record” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1978), 950.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York City: Checkmark Books, 2001. p. 200 ISBN 0-8160-4161-X

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York City: Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 106 ISBN 0-8154-1038-7

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York City: Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 138 ISBN 0-06-092331-8

- ↑ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. p. 277. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York City: Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 334-5 ISBN 0-06-092331-8

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York City: Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 107 ISBN 0-8154-1038-7

- ↑ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1998. p.277.

- ↑ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. p. 277.

- ↑ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York City: Checkmark Books, 2001. p. 200-1 ISBN 0-8160-4161-X

- ↑ Thomas, Dwight. “Poe in Philadelphia, 1838-1844: A Documentary Record” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1978), 950. Poe wrote: "All School-books are necessarily made in a similar way."

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay. "Poe's Greatest Hit". Natural History, CII, No. 7, July 1993, pp. 10-19.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay. Dinosaur in a Haystack. NY: Harmony Books, 1995. ISBN 0-517-70393-9

- ↑ Lienhard, John H. "No. 1090: Poe's Conchology." Engines of Our Ingenuity. UH.edu

- ↑ Lienhard, John H. "No. 1090: Poe's Conchology."

External links

- Introduction to The Conchologist's First Book at the E. A. Poe Society

- Online version of the 1839 first edition.

- Online version of the 1840 second edition