The Calculus Affair

| The Calculus Affair (L'Affaire Tournesol) | |

|---|---|

|

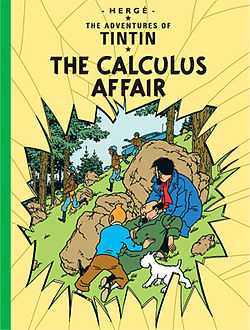

Cover of the English edition | |

| Date | 1956 |

| Series | The Adventures of Tintin |

| Publisher | Casterman |

| Creative team | |

| Creator | Hergé |

| Original publication | |

| Published in | Tintin magazine |

| Date of publication | 22 December 1954 – 22 February 1956 |

| Language | French |

| Translation | |

| Publisher | Methuen |

| Date | 1960 |

| Translator |

|

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | Explorers on the Moon (1954) |

| Followed by | The Red Sea Sharks (1958) |

The Calculus Affair (French: L'Affaire Tournesol) is the eighteenth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised weekly in the newly established Tintin magazine from December 1954 to February 1956. The narrative follows the attempts of young reporter Tintin, his dog Snowy, and friend Captain Haddock to rescue Professor Calculus, a scientist who has developed a machine capable of destroying objects with sound waves, after the latter is the subject to kidnapping attempts from the competing countries of Borduria and Syldavia.

Hergé continued The Adventures of Tintin with The Red Sea Sharks, while the series itself became a defining part of the Franco-Belgian comics tradition. Critically well-received, various commentators have described The Calculus Affair as one of the best Adventures of Tintin. The story was adapted for both the 1957 Belvision animated series, Hergé's Adventures of Tintin, and for the 1991 animated series The Adventures of Tintin by Ellipse and Nelvana.

Synopsis

During a thunderstorm, glass and porcelain items at Marlinspike Hall shatter unexplainably. Insurance salesman Jolyon Wagg arrives at the house, annoying Captain Haddock. Gunshots are heard in the Hall's grounds, and Tintin and Haddock discover a wounded man speaking in a foreign accent who soon disappears. The next morning, Professor Calculus leaves for Geneva to attend a conference in nuclear physics. Tintin and Haddock use the opportunity to investigate Calculus' laboratory, there discovering that his experiments were responsible for the glass-shattering of the previous night. While exploring, they are attacked by a stranger, who then escapes; fearing the Calculus is in danger, Tintin, Haddock, and Snowy head for Geneva. In Geneva, they learn that Calculus has gone to Nyon to meet Professor Topolino, an expert in ultrasonics. Driving there in a taxi, their car is attacked by two men in another car, who force theirs into Lake Geneva. Surviving the attack, Tintin and Haddock continue to Nyon, where they find Topolino bound and gagged in his cellar. As Tintin questions the professor, the house blows up, but they all survive.

Tintin and Haddock meet the detectives Thomson and Thompson, who reveal that the wounded man at Marlinspike was Syldavian. Tintin surmises that Calculus had invented an ultrasonic device capable of being used as a weapon of mass destruction, which both Syldavian and Bordurian intelligence agents are now seeking to obtain. Discovering that Bordurian spies have kidnapped Calculus and are holding him hostage in their Rolle embassy, Tintin and Haddock seek to rescue him, but during the attempt he is captured by Syldavian agents, who are able to escape by plane to their home country. The next morning, Tintin and Haddock learn that Bordurian fighters shot down the Syldavian plane and captured Calculus, who is now being held in Borduria. They travel to Borduria's capital, Szohôd, intent on rescuing him.

In the city, they are escorted to their hotel by agents of the Bordurian secret police, who have been ordered to monitor the duo by police chief Colonel Sponz. Aware that they are being monitored, Tintin and Haddock escape the hotel and hide in the opera house, where Bianca Castafiore is performing. When police come searching for them, they hide in Castafiore's closet; after Sponz comes to visit Castafiore in her dressing room, Tintin is able to steal papers that will secure Calculus' release from Bakhine Prison from his coat pocket. After disguising themselves as officials from the Red Cross, Tintin and Haddock are able to get Calculus released from prison and with him escape from Broduria aboard a tank. Back at Marlinspike Hall, Calculus reveals that he forgot to take his plans for the ultrasonic device with him to Geneva, and that he had left it at home all along; he destroys the plans so that they could not be used to create a weapon.

History

Background

The Calculus Affair was produced at the height of the Cold War and reflected the conflict's tensions.[1] At the time, espionage thrillers were proving popular in France and Belgium.[2] Started in December 1954, The Calculus Affair marked a return to the single volume format which was to persist for the rest of the series.[3] Before working on the book, Hergé would draft his techniques in pencil; after confirming his sketches, he would work over the drawings and text in ink. With the development of his own studio, he selected the best sketch from a number of sketches and traced it onto the page he was creating.[3]

The Calculus Affair introduces three recurring characters into the series. The first is Jolyon Wagg, a Belgian insurance salesman who annoys Haddock when he invited himself to Marlinspike.[4] According to Michael Farr, Wagg, was "the proverbial bore".[5] For the name of Jolyon Wagg (Séraphin Lampion in the original French version), Hergé initially chose Crampon, which was derived from the French expression, "Quel Crampon!" (English: "What a leech!"). Hergé however rejected Crampon as he found it too explicit and harsh-sounding and settled on Lampion.[6] Hergé named Wagg's insurance company Assurances Mondass, although for the English translation it became The Rock Bottom Insurance.[5][7]

The second new character to be introduced to the story was Cutts the butcher; Hergé named the character Sanzot, a pun on sans-os ("without bones") which referenced his profession.[8] Another addition to The Calculus Affair was the Bordurian head of secret police Colonel Sponsz, whose name is derived from the Brussels dialect for a sponge (éponge in French).[9] Hergé used his brother, Paul Remi, as the model for Sponsz, although he was also influenced by the image of the Austrian American filmmaker, Erich von Stroheim.[9] Topolino, the name of the professor Calculus goes to meet regarding his invention in ultrasound, is also the name by which Mickey Mouse is known in Italy.[3]

Influences

A key influence on the plot of The Calculus Affair was an article that Hergé had read in a February 1954 issue of the Belgian weekly La Face à main. In this article, it was reported that there had been a number of incidents along the road from Portsmouth to London in southern England in which motorists had reported their windshield spontaneously shattering; the article's author suggested that it may have been caused by experiments undertaken in a nearby secret facility.[10] To develop this plot further, Hergé consulted Professor Armand Delsemme , an astrophysicist at Liège.[11]

Hergé requested that Jean Dupont, the editor of his Swiss publisher L'Écho illustré, send him documentation on Swiss railways which he could draw from.[12] He also requested that his Swiss friend Charly Fornora send him a bottle of Valais wine which he use as a reference.[12] Hergé subsequently travelled to Switzerland in order to gain accurate sketches of scenes around Geneva from which to draw upon in the story; these included at Geneva Cointrin International Airport, Genève-Cornavin railway station, and the Cornavin Hotel,[lower-alpha 1] as well as the road through Cervens and Topolino's house in Nyon.[15] Despite this realism, a number of minor errors were made.[16] As a result of his detailed observation, Hergé's depiction of Switzerland was free from national clichés.[17]

.svg.png)

Hergé's depiction of Borduria was based on Eastern Bloc countries.[2] Their police force was modeled on the Soviet KGB.[2] Hergé named the political leader of Borduria Plekszy-Gladz, a pun on plexiglas, although the English translators renamed him Kûrvi-Tasch ("curvy tash"), a reference to the fact that the leader's curved moustache, inspired by that of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, was a prominent symbol in Borduria.[18] As evidence for the accuracy of Hergé's depiction of an Eastern Bloc city, reporter Michael Farr highlighted that Borduria's Kûrvi-Tasch Platz closely resembled East Berlin's Platz der Republik, which would only be completed in the 1970s.[13] All of the furniture in the Bordurian police headquarters was drawn from that found in the Studios Hergé premises.[19]

The idea of a sonic weapon was one which had been unsuccessfully pioneered by German scientists under the control of Albert Speer during World War II.[20] The book in Professor Topolino's house, German Research in World War II by Leslie E. Simon, really existed and was published in 1947. Simon was a retired Major General in the U.S. Army. Hergé also preserved the English language in which the book was published in his strips, but altered the cover to remove a prominent swastika.[21] The inclusion of the book is one of the few times that there is any reference to the Second World War in The Adventures of Tintin.[2]

Hergé's decision to name a character Topolino was a reference to Walt Disney, whose character of Mickey Mouse was known as Topolino in Italian.[22] Hergé included a reference to his friend and colleague, the former opera singer Edgar P. Jacobs, into the story, adding a figure known as Jacobini to the billing on the opera performance alongside Castafiore.[23] He also inserted a cameo of himself as a reporter into the final scene of the story.[23]

Publication

The Calculus Affair began serialisation in Tintin magazine's Christmas edition on 22 December 1954, and continued to appear there until 22 February 1956.[24] It would be the first of The Adventures of Tintin to be serialised without interruption since Red Rackham's Treasure.[25] It then began serialisation in the French edition of Tintin in February 1955.[4] It was then published in collected book form as L'Affaire Tournesol by Casterman in 1956.[4] For this volume Hergé had designed a front cover design; initially it simply showed Tintin and Haddock hiding Calculus from Bordurian soldiers, but he subsequently added shattered glass around the edges for dramatic effect.[14]

Critical analysis

Harry Thompson opined that while the story's ending was somewhat unsatisfactory and rushed, it remained "probably the best of all the Tintin books".[17] Biographer Benoît Peeters agreed, describing it as "Hergé's masterwork", "a masterpiece of the classic strip cartoon".[26] Elsewhere, he referred to it as "one of his most brilliant books", describing Wagg as "the last great figure of The Adventures of Tintin".[27] He added that the story had "the atmosphere of a spy novel worthy of John Buchan or Eric Ambler".[28] Similarly, Michael Farr described The Calculus Affair as "one of Hergé's finest creations".[3] Biographer Pierre Assouline stated that the "illustrations and the scenario are vibrant and rich; the story thread holds from beginning to end".[22]

Jean-Marc Lofficier and Randy Lofficier stated that the introduction of Wagg and Cutts represented "yet another turning point in the series", praising the characterisation of Wagg as "bitter and successful social satire".[29] They were critical about the inclusion of Syldavians as an antagonist in the story, stating that their attempts to kidnap Calculus "strains believability" because they had appeared as allies of Calculus and Tintin in both the preceding two-part moon adventure and in the earlier King Ottokar's Sceptre.[2] Ultimately, they felt that "the plot seems somewhat shoe-horned into the familiar universe" and "one feels that Hergé's heart was not really much into the action part of the story", ultimately awarding it three stars out of five.[30]

Literary critic Tom McCarthy believed that The Calculus Affair aptly illustrates how Tintin is no longer political in the manner that he was in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and Tintin in the Congo; instead, he travels to Borduria to rescue Calculus, "not to fight or expose totalitarianism".[31] Moving on to Calculus, he stated that in this story he was "a genius compromised", with his role being a "counter-position to, or flip-side of, the one he represented in the moon books".[32] He noted that when Tintin and Haddock arrive in Borduria, they are "treated as honoured guests but are in fact prisoners of the police state", a reversal of the situation in The Blue Lotus in which Tintin believes himself a prisoner but is in fact a guest.[33] He stated that as with The Crab with the Golden Claws, The Calculus Affair was "one long tobacco-trail" with cigarettes representing clues throughout the story.[34] Turning his attention to the opera house scene in which Tintin and Haddock spy upon Sponz and Castafiore, he compared it to the scene in David Lynch's film Blue Velvet in which Jeffrey Beaumont spies on the sexual activities of Dorothy Vallens and Frank Booth.[35]

Adaptations

In 1957, the animation company Belvision Studios produced a string of colour adaptations based upon Hergé's original comics, adapting eight of the Adventures into a series of daily five-minute episodes. The Calculus Affair was the eighth such story in the second series, being directed by Ray Goossens and written by Greg, himself a well-known cartoonist who in later years would become editor-in-chief of Tintin magazine.[36]

In 1991, a collaboration between the French studio Ellipse and the Canadian animation company Nelvana adapted 21 of the stories into a series of episodes, each 42 minutes long. The Calculus Affair was the sixteenth episode of The Adventures of Tintin to be produced, although it ran half as long as most of the others. Directed by Stéphane Bernasconi, the series has been praised for being "generally faithful", with compositions having been actually directly taken from the panels in the original comic book.[37]

References

Notes

- ↑ The room at the Cornavin Hotel in which Calculus stays (Room 122, fourth floor) did not exist. The hotel management later sent Hergé a letter explaining that it was not possible to stay in the Professor's room.[13] In response to the number of letters received addressed to Professor Calculus, the hotel management later put up a plaque for room 122.[14]

Footnotes

- ↑ Peeters 1989, p. 100; Farr 2001, p. 145; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 68.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 68.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Farr 2001, p. 145.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 67.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Farr 2001, p. 148.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 158; Farr 2007, p. 98.

- ↑ Farr 2007, p. 98.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 158; Farr 2001, p. 67; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Thompson 1991, p. 159; Farr 2001, p. 148.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, pp. 250–251.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 176; Peeters 2012, p. 55.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Goddin 2011, p. 56.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Farr 2001, p. 146.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Assouline 2009, p. 176.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 152; Farr 2001, pp. 145–146; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 69; Peeters 2012, p. 252.

- ↑ Goddin 2011, p. 60.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Thompson 1991, p. 160.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 146; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 68.

- ↑ Goddin 2011, p. 71.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 159; Farr 2001, p. 145.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 145; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 68.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Assouline 2009, p. 175.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Farr 2001, p. 149.

- ↑ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 67; Peeters 2012, p. 250, 253.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 253.

- ↑ Peeters 1989, p. 99.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 251.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 252.

- ↑ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, p. 49.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, p. 71.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, p. 137.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, pp. 106–108.

- ↑ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 90.

Bibliography

- Apostolidès, Jean-Marie (2010) [2006]. The Metamorphoses of Tintin, or Tintin for Adults. Jocelyn Hoy (translator). Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6031-7.

- Assouline, Pierre (2009) [1996]. Hergé, the Man Who Created Tintin. Charles Ruas (translator). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

- Farr, Michael (2001). Tintin: The Complete Companion. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5522-0.

- Farr, Michael (2007). Tintin & Co. London: Egmont. ISBN 978-1-4052-3264-7.

- Goddin, Philippe (2011). The Art of Hergé, Inventor of Tintin: Volume 3: 1950-1983. Michael Farr (translator). San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0867197631.

- Hergé (1960) [1956]. The Calculus Affair. Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner (translators). London: Egmont. ISBN 978-1-4052-0629-7.

- Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Lofficier, Randy (2002). The Pocket Essential Tintin. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-17-6.

- McCarthy, Tom (2006). Tintin and the Secret of Literature. London: Granta. ISBN 978-1-86207-831-4.

- Peeters, Benoît (1989). Tintin and the World of Hergé. London: Methuen Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-416-14882-4.

- Peeters, Benoît (2012) [2002]. Hergé: Son of Tintin. Tina A. Kover (translator). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0454-7.

- Thompson, Harry (1991). Tintin: Hergé and his Creation. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-52393-3.

External links

- The Calculus Affair at the Official Tintin Website

- The Calculus Affair at Tintinologist.org