The Boat Race 1849 (December)

| 10th Boat Race | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 15 December 1849 | ||

| Winner | Oxford | ||

| Margin of victory | Cambridge disqualified | ||

| Winning time | No time | ||

| Overall record (Cambridge–Oxford) | 7–3 | ||

| Umpire |

Mr Fellowes (Leander Club) | ||

| |||

The 10th Boat Race took place on the River Thames on 15 December 1849. Typically held annually, the event is a side-by-side rowing race between crews from the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. The race was won by Oxford who triumphed over Cambridge after they were disqualified. It is the only time the Boat Race has been held twice in a calendar year, and as of 2015 remains the only time the event has been decided as a result of a disqualification.

Background

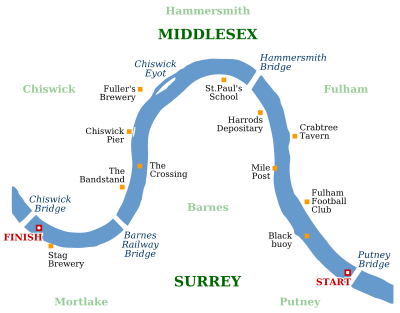

The causes of our defeat were partial want of condition, a bad boat (built by Hall), and bad steering. We led from the moment of starting to Chiswick Eyot; but here our coxswain took us over the back-water on the Surrey side, and without any apparent diminution in our efforts, the boat seemed to stop almost dead, the Cantabs came up in the midsream and tide, and passed like a shot. The race was then at an end.

The Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing competition between the University of Oxford (sometimes referred to as the "Dark Blues")[2] and the University of Cambridge (sometimes referred to as the "Light Blues").[2] The race was first held in 1829, and since 1845 has taken place on the 4.2-mile (6.8 km) Championship Course on the River Thames in southwest London.[3][4]

Cambridge had beaten Oxford "easily" in the race earlier that year. It was as a result of the manner of the defeat, and with doubts over the construction of the Oxford boat that they issued a challenge to Cambridge University Boat Club in October to race again in December.[5][6] The invitation to race was "immediately accepted."[7] Cambridge held the overall lead, with seven victories to Oxford's two.[8]

Crews

Oxford's crew contained four rowers who had featured in the previous race in March, with Chitty, Steward, Sykes and Rich returning for the Dark Blues. Cambridge welcomed back five rowers and the cox, George Booth. The difference in weight between the crews was marginal, Oxford's rowers weighing an average of just under 11 st 6 lb (72.4 kg) were 0.125 pounds (0.06 kg) per man heavier than Cambridge.[9]

| Seat | Cambridge |

Oxford | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | College | Weight | Name | College | Weight | |||

| Bow | A. T. Baldry | 1st Trinity | 10 st 10 lb | J. J. Hornby | Brasenose | 11 st 8 lb | ||

| 2 | H. P. Pellew | 3rd Trinity | 11 st 0 lb | W. Houghton | Brasenose | 11 st 2 lb | ||

| 3 | A. R. De Rutzen | 3rd Trinity | 11 st 8 lb | James Wodehouse | Exeter | 11 st 7lb | ||

| 4 | J. C. Holden (P) | 3rd Trinity | 11 st 11 lb | J. W. Chitty | Balliol | 11 st 9 lb | ||

| 5 | W. L. G. Bagshawe | 3rd Trinity | 12 st 0 lb | J. Aitken | Exeter | 12 st 1 lb | ||

| 6 | H. J. Miller | 3rd Trinity | 12 st 0 lb | C. H. Steward | Oriel | 12 st 2 lb | ||

| 7 | W. C. Hodgson | 1st Trinity | 11 st 3 lb | J. J. Sykes | Worcester | 10 st 2 lb | ||

| Stroke | J. C. Wray | 2nd Trinity | 11 st 0 lb | W. G. Rich (P) | Christ Church | 11 st 2 lb | ||

| Cox | George Booth | 1st Trinity | 10 st 12 lb | Richard Wm. Cotton | Christ Church | 9 st 0 lb | ||

| Source:[9] (P) – boat club president[10] | ||||||||

Race

Oxford won the toss and elected to start from the Middlesex station, leaving Cambridge with Surrey.[11] Weather conditions were poor: rain and a strong wind provided a "pitiless pelting" to spectators and the crews alike.[12] Although pre-race betting indicated no clear favourite, the high winds were thought to provide Cambridge with a slight advantage "as their style of rowing was deemed to be more suitable to stormy weather" and so the Light Blues went into the race as marginal favourites.[12]

Both crews were on the river before 3pm in boats constructed by Searle and Sons, described as "masterpieces of art", complete with splashboards to reduce the amount of water taken on board.[11] Cambridge made the better start and were clear by the Searles boathouse. They increased the lead by a further half-a-length and held it for another 0.5 miles (0.8 km), at which point Oxford produced a "marked improvement in speed" and began to reduce the deficit.[11] As Cambridge had already moved in front of Oxford, they steered back towards the Surrey shore in preparation for shooting Hammersmith Bridge. In doing so, a collision ensued, causing Oxford to come to halt.[13] Although Cambridge made a three-to-four length headstart, Oxford's subsequent pace combined with Cambridge's wayward steering reduced the gap and by the end of the race, the boats were nearly level.[13]

Immediately upon the conclusion, the race umpire, Thomas Howard Fellows of Leander Club declared the result in favour of Oxford, disqualifying Cambridge for the foul.[14] Cambridge, although believing the foul was against them, did not object to the decision. The Cambridge University Boat Club secretary Charles Bagot wrote: "It is much to be regretted that a foul should have taken place, as, besides rendering the race an imperfect test of the merits of the respective crews, it very much disturbed the harmony and good feeling which should exist between members of the rival Universities in such contests."[15] As of 2015, it remains the only time that the Boat Race has been decided by a disqualification.[5][8]

References

Notes

- ↑ MacMichael, p.154

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Dark Blues aim to punch above their weight". The Observer. 6 April 2003. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Oliver (25 March 2014). "University Boat Race 2014: spectators' guide". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ↑ "The Course". The Boat Race Company Limited. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Early races". The Boat Race Company Limited. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ↑ MacMichael, p.155

- ↑ MacMichael, p. 158

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Boat Race – Results". The Boat Race Company Limited. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 MacMichael p. 160

- ↑ Burnell pp. 50–51

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 MacMichael, p. 162

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 MacMichael, p. 161

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 MacMichael, p. 163

- ↑ MacMichael, p. 164

- ↑ MacMichael, p. 165

Bibliography

- Burnell, Richard (1979). One Hundred and Fifty Years of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race. Precision Press. ISBN 978-0-9500638-7-4.

- MacMichael, William Fisher (1870). The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Races: From A.D. 1829 to 1869. Deighton.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||