The Atomic Cafe

| The Atomic Café | |

|---|---|

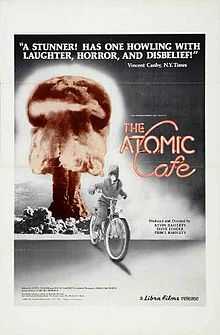

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by |

Jayne Loader Kevin Rafferty Pierce Rafferty |

| Produced by |

Jayne Loader Kevin Rafferty Pierce Rafferty |

| Written by |

Jayne Loader Kevin Rafferty Pierce Rafferty |

| Music by |

Consultant: Charles Wolfe |

| Edited by |

Jayne Loader Kevin Rafferty |

Production company |

The Archives Project |

| Distributed by |

Libra Films Journeyman Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 86 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The Atomic Café is a 1982 American documentary film produced and directed by Jayne Loader, Kevin Rafferty, and Pierce Rafferty.[1]

Synopsis

The film covers the beginnings of the era of nuclear warfare, created from a broad range of archival film from the 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s - including newsreel clips, television news footage, U.S. government-produced films (including military training films), advertisements, television and radio programs. News footage reflected the prevailing understandings of the media and public.

Though the topic of atomic holocaust is a grave matter, the film approaches it with black humor. Much of the humor derives from the modern audience's reaction to the old training films, such as the Duck and Cover film shown in schools. A quote to illustrate what can be perceived as black humor culled from the archives:

- Army information film: When not close enough to be killed, the atomic bomb is one of the most beautiful sights in the world.

Historical context

Atomic Café was released at the height of nostalgia and cynicism in America. By 1982, Americans lost much of their faith in their government following the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, and the seemingly never-ending arms race with the Soviet Union.[2] Atomic Café reflects and reinforces this idea as it exposes how the atomic bomb’s dangers were both downplayed and how the government manipulated films, such as when President Truman calls the atomic bomb a gift from God.

Atomic Café was also released during the Reagan Administration’s forced civil defense revival.[3] Barry Posen and Stephen Van Evera explain this revival in their article “Defense Policy and the Reagan Administration: Departure from Containment” published in International Security. They argue that in 1981–82 the Reagan Administration was moving from an essentially defensive grand strategy of containment to a more offensive strategy. Due to the greater demands of its more offensive strategy “the Reagan Administration ... proposed the biggest military buildup since the Korean War.”[4] Of key relevance to "Atomic Café," the Reagan move toward offense included the adoption of a more aggressive nuclear strategy that required a large U.S. nuclear buildup. Containment only required that U.S. strategic nuclear forces be capable of one mission: inflicting unacceptable damage on the Soviet Union even after absorbing an all-out Soviet surprise attack. To this "assured destruction" mission the Reagan administration added a second "counterforce" mission, which required the capacity to launch a nuclear first strike against Soviet strategic nuclear forces that would leave the Soviets unable to inflict unacceptable damage on the U.S. in retaliation. The U.S. had always invested in counterforce but the Reagan administration put even greater emphasis on it. The counterforce mission was far more demanding than the assured destruction mission, and required a vast expansion of U.S. nuclear forces to fulfill. Civil defense was a component of a counterforce strategy, as it reduced Soviet retaliatory capacity, hence civil defense was a candidate for more spending under Reagan's counterforce nuclear strategy. Posen and Van Evera argue that this counterforce strategy was a warrant for an open-ended U.S. nuclear buildup.

Bob Mielke in his article “Rhetoric and Ideology in the Nuclear Test Documentary” for Film Quarterly discussed the ideal release of "Atomic Café", “This satire feature was released at the height of the nuclear freeze movement (which was in turn responding to the Reagan administration’s surreal handling of the arms race.)”[5]

Production

The film was produced over a five-year period through the collaborative efforts of three directors: Jayne Loader and brothers Kevin and Pierce Rafferty. For this film, the Rafferty brothers and Loader formed the production company "Archives Project Inc." The filmmakers opted not to use narration, and instead they deployed carefully constructed sequences of film clips to make their points. Jayne Loader has referred to The Atomic Cafe as a compilation verite, meaning that it is a compilation film with no "Voice of God" narration and no new footage added by the filmmakers.[6] The soundtrack utilizes atomic-themed songs from the Cold War era to underscore the themes of the film.[7]

The film cost $300,000 to make. The group did receive some financial support from outside sources, including the Film Fund; a Washington, D.C. based non-profit.[8] Grants comprised a nominal amount of the team’s budget, and the film was largely funded by the filmmakers themselves. Jayne Loader stated in an interview, “Had we relied on grants, we would have starved" [9] Pierce Rafferty helped to support the team and the film financially by working as a consultant and researcher on several other documentary films including El Salvador—Another Vietnam, With Babies and Banners, and The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter.[10] The Rafferty brothers had also received an inheritance that they used to support the team during the five years it took to make the film [9] About 75% of the film is made up of government materials that were in the public domain. Though they could use those public domain materials for free, they had to make copies of the film at their own expense. This along with the newsreel and commercial stock footage that comprises the other 25% of the film (along with the music royalties) represents the bulk of the trio’s expenditures.[10]

Release

The film was released on March 17, 1982 in New York City, New York. In August 1982, a tie-in companion book of the same name, written by Kevin Rafferty, was released by Bantam Books, ISBN 0-553-01462-5.[11]

Home media

20th Anniversary Edition of the film was released in DVD format in Region 1 on March 26, 2002 by New Video Group.[11]

In 1995, an adult educational CD-ROM companion to The Atomic Cafe with many of the clips and other materials from the film, plus additional clips from declassified films, audio, photographs, and text files that archive the history, technology, and culture of the Nuclear Age, was released by Public Shelter; a web site based company Jayne Loader and her husband Eric Schwaab began. The Public Shelter CD-ROM release only sold 500 copies and failed to find a publisher.[12]

Reception

Critical response

When the film was released, film critic Roger Ebert discussed the style and methods the filmmakers used, writing, "The makers of The Atomic Cafe sifted through thousands of feet of Army films, newsreels, government propaganda films and old television broadcasts to come up with the material in their film, which is presented without any narration, as a record of some of the ways in which the bomb entered American folklore. There are songs, speeches politicians, and frightening documentary footage of guinea-pig American troops shielding themselves from an atomic blast and then exposing themselves to radiation neither they nor their officers understood."[13]

Critic Vincent Canby praised the film, calling the film "a devastating collage-film that examines official and unofficial United States attitudes toward the atomic age" and a film that "deserves national attention."[7]

More recently, critic Glenn Erickson discussed the editorial message of the film's producers: "The makers of The Atomic Cafe clearly have a message to get across, and to achieve that goal they use the inherent absurdity of their source material in creative ways. But they're careful to make sure they leave them essentially untransformed. When we see Nixon and J. Edgar Hoover posing with a strip of microfilm, we know we're watching a newsreel. The content isn't cheated. Except in wrapup montages, narration from one source isn't used over another. When raw footage is available, candid moments are seen of speechmakers (including President Truman) when they don't know the cameras are rolling. Caught laughing incongruously before a solemn report on an atom threat, Truman comes off not as callous, but human."

The review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reported that 100% of critics gave the film a positive review, based on 14 reviews."[14]

Deirdre Boyle, an Associate Professor and Academic Coordinator of the Graduate Certificate in Documentary Media Studies at The New School and an author of Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited, claimed that "By compiling propaganda or fictions denying 'nuclear-truth', The Atomic Cafe reveals the American public’s lack of resistance to the fear generated by the government propaganda films and the misinformation they generated. Whether Americans of the time lacked the ability to resist or reject this misinformation about the atomic bomb is a debatable truth.”[15]

Accolades

- Wins

- Boston Society of Film Critics: BSFC Award, Best Documentary; 1983.

- Nomination

- British Academy Film Awards: Flaherty Documentary Award, Kevin Rafferty, Jayne Loader and Pierce Rafferty; 1983.

Soundtrack

A vinyl LP record of the film's soundtrack was released in 1982 by Rounder Records. Some of the credits for the record, include: co-produced by Charles Wolfe, The Archives Project (Jayne Loader, Kevin Rafferty and Pierce Rafferty), album cover artwork by Dennis Pohl, cover design by Mel Green, and booklet text by Charles Wolfe.[16]

Track listing

- Side One

- 1. "Atom and Evil" by the Golden Gate Quartet

- 2. Audio Clip: Maj. Thomas Ferebee, "Enola Gay" bombardier, 08/15/45

- 3. "When the Atom Fell" by Karl and Harty

- 4. Audio Clips: President Harry S Truman, 08/09/45; Capt. Kermit Beehan, "The Great Artiste" bombardier, 08/15/45

- 5. "Win the War Blues" by Sonny Boy Williamson II

- 6. Audio Clip: David E. Lilienthal, the first Chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission

- 7. "Atomic Power" by the Buchanan Brothers

- 8. Audio Clip: Winston Churchill, 03/31/49

- 9. "Jesus Hits Like an Atom Bomb" by Lowell Blanchard and The Valley Trio

- 10. Audio Clip: Rep. James E. Van Zandt (Republican), Penn., 05/08/53

- 11. "When They Drop the Atomic Bomb" by Jackie Doll and His Pickled Peppers

- 12. "Atomic Sermon" by Billy Hughes and his Rhythm Buckeroos

- 13. "Old Man Atom" by Sons of the Pioneers

- Side Two

- 1. "Uranium" by The Commodores

- 2. "50 Megatons" by Sonny Russell

- 3. "Atom Bomb Baby" by The Five Stars

- 4. "Satellite Baby" by Skip Stanley

- 5. "Sputniks and Mutniks" by Ray Anderson and the Homefolks

- 6. "Atomic Cocktail" by Slim Gaillard Quartette

- 7. "Atomic Love" by Little Caesar with the Red Callendar Sextette

- 8. "Atomic Telephone" by Spirits of Memphis Quartet

- 9. "Red's Dream" by Louisiana Red

The Internet Movie Data Base (IMDB) lists the following additional songs on the soundtrack of The Atomic Cafe: [17]

- This Cold War With You by Floyd Tillman

- Rosza Conducts Rosza by Miklós Rózsa conducting the Frankenland State Symphony

- I'm No Communist by Carson Robison

- Thirteen Women by Bill Haley and the Comets

- Flying Home by Glenn Miller and the Army Air Force Band

- The Hydrogen Bomb by Al Rogers and His Rocky Mountain Boys

- Hungarian Rhapsody #2 in C Sharp Minor by Arthur Fiedler Conducting the Boston Pops

- Mussorgsky - Pictures at an Exhibition by Charles Mackerras conducting the New Philharmonic Orchestra

See also

- Atomic Age

- Culture during the Cold War

- Duck and cover

- How to Photograph an Atomic Bomb

- List of films about nuclear issues

- Nuclear weapons in popular culture

References

- ↑ The Atomic Cafe at the American Film Institute Catalog.

- ↑ McLane Betsy. "Film Quarterly", film review, Spring 1983. Last accessed: November 27, 2012.

- ↑ Conelrad: All Things Atomic. The Atomic Cafe, Jayne Loader Interview. Last accessed: November 26, 2012.

- ↑ Posen, R. Barry "Defense Policy and the Reagan Administration: Departure from Containment", Journal article. Last accessed: November 27, 2012.

- ↑ Mielke Bob. "Film Quarterly", film review, Spring 2005. Last Accessed: November 27, 2012.

- ↑ Conelrad: All Things Atomic. The Atomic Cafe, Jayne Loader Interview. Last accessed: February 20, 2011.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Canby, Vincent. The New York Times, film review, March 17, 1982. Last accessed: February 20, 2011.

- ↑ Trebbe, Ann L. "Cinema Verties." The Washington Post 6 Nov. 1981, C3 sec.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 The Atomic Cafe, Jayne Loader Interview. Last accessed: November 14, 2011.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Harrington, Richard. "Blast from the Past: 'Atomic Cafe': A Stunning Cold War Collage." The Washington Post 14 May 1982, C1 sec.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Amazon.com

- ↑ Wen, Howard. Dallas Observer, "GROUND ZERO: Atomic Cafe filmmaker Jayne Loader has won raves for her CD-ROM Public Shelter, but calls the 'new medium' a dud," June 27, 1996. Last accessed: February 20, 2011.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. Chicago Sun-Times, film review, January 1, 1982. Last accessed: February 20, 2011.

- ↑ The Atomic Cafe at Rotten Tomatoes. Last accessed: February 20, 2011.

- ↑ Boyle, Deirdre, “The Atomic Cafe”, Cineaste 12.2, 1982, p. 39.

- ↑ Conelrad web site, Atomic Cafe: History Done Right. Last accessed: February 20, 2011.

- ↑ "The Atomic Cafe (1982) Soundtracks". Retrieved 2014-01-09.