Thach Weave

The Thach Weave (also known as a Beam Defense Position) is an aerial combat tactic developed by naval aviator John S. Thach of the United States Navy soon after the United States' entry into World War II.

Thach had heard, from a report published in the 22 September 1941 Fleet Air Tactical Unit Intelligence Bulletin, of the Japanese Mitsubishi Zero's extraordinary maneuverability and climb rate. Before even experiencing it for himself, he began to devise tactics meant to give the slower-turning American F4F Wildcat fighters a chance in combat. While based in San Diego, he would spend every evening thinking of different tactics that could overcome the Zero's maneuverability, and would then test them in flight the following day.

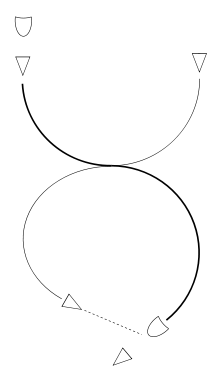

Working at night with matchsticks on the table, he eventually came up with what he called "Beam Defense Position", but which soon became known as the "Thach Weave". It was executed either by two fighter aircraft side-by-side or by two pairs of fighters flying together. When an enemy aircraft chose one fighter as his target (the "bait" fighter; his wingman being the "hook"), the two wingmen turned in towards each other. After crossing paths, and once their separation was great enough, they would then repeat the exercise, again turning in towards each other, bringing the enemy plane into the hook's sights. A correctly executed Thach Weave (assuming the bait was taken and followed) left little chance of escape to even the most maneuverable opponent.

Thach called on Ensign Edward "Butch" O'Hare, who led the second section in Thach's division, to test the idea. Thach took off with three other Wildcats in the role of defenders, Butch O'Hare meanwhile led four Wildcats in the role of attackers. The defending aircraft had their throttles wired (to restrict their performance), while the attacking aircraft had their engine power unrestricted - this simulated an attack by superior fighter aircraft.[1]

Trying a series of mock attacks, Butch found that in every instance Thach's fighters, despite their power handicap, had either ruined his attack or actually maneuvered into position to shoot back. After landing, Butch excitedly congratulated Thach: "Skipper, it really worked. I couldn't make any attack without seeing the nose of one of your airplanes pointed at me."

Thach carried out the first test of the tactic in combat during the Battle of Midway in June 1942, when a squadron of Zeroes attacked his flight of four Wildcats. Thach's wingman, Ensign R. A. M. Dibb, was attacked by a Japanese pilot and turned towards Thach, who dove under his wingman and fired at the incoming enemy aircraft's belly until its engine ignited.

The maneuver soon became standard among US Navy pilots and was adopted by USAAF pilots.

Marines flying Wildcats from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal also adopted the Thach Weave. The tactic initially confounded the Japanese Zero pilots flying out of Rabaul. Saburō Sakai, the famous Japanese ace, relates their reaction to the Thach Weave when they encountered Guadalcanal Wildcats using it:[2]

For the first time Lt. Commander Tadashi Nakajima encountered what was to become a famous double-team maneuver on the part of the enemy. Two Wildcats jumped on the commander's plane. He had no trouble in getting on the tail of an enemy fighter, but never had a chance to fire before the Grumman's team-mate roared at him from the side. Nakajima was raging when he got back to Rabaul; he had been forced to dive and run for safety.

The maneuver proved so effective that American pilots also used it during the Vietnam War, and it remains an applicable tactic as of 2013.[3]

Notes

- ↑ "APPENDIX FOURTEEN: UNITED STATES NAVY FIGHTER TACTICS". The Battle of Midway. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "Naval Aviation News" July-August 1993:

- ↑ Ewing, Steve. "Thach Weave". https://books.google.com.co/books''. Google Books. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

Further reading

- Ewing, Steve (2004), Thach Weave: The Life of Jimmie Thach, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 1-59114-248-2

- Lundstrom, John (1984), The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway (2005 paperback ed.), Naval Institute Press, ISBN 1-59114-471-X. It has an extended discussion of fighter tactics of the time, including an in-depth discussion of the development of the Thach Weave.

- Mason Jr., John T. (1986), The Pacific War Remembered: An Oral History Collection, Naval Institute Press, ISBN 0-87021-522-1. It contains an account by John Thach about the development of the Weave and another about its use in Midway.

External links

| ||||||||||