Tangent half-angle formula

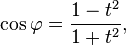

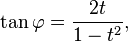

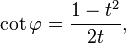

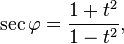

In trigonometry, the tangent half-angle formulas relate the tangent of one half of an angle to trigonometric functions of the entire angle. They are as follows:

There are also a number of different forms:

Proofs

Algebraic proofs

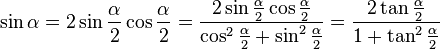

Use double-angle formulae and sin2α + cos2α = 1,

then

Q.E.D.

Geometric proofs

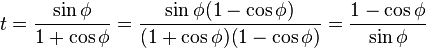

In the unit circle, t = tan(φ/2). According to similar triangles,  . It follows that

. It follows that  .

.

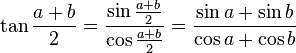

It is clear from the rhombus figure, right, that  .

.

The tangent half-angle substitution in integral calculus

In various applications of trigonometry, it is useful to rewrite the trigonometric functions (such as sine and cosine) in terms of rational functions of a new variable t. These identities are known collectively as the tangent half-angle formulae because of the definition of t. These identities can be useful in calculus for converting rational functions in sine and cosine to functions of t in order to find their antiderivatives.

Technically, the existence of the tangent half-angle formulae stems from the fact that the circle is an algebraic curve of genus 0. One then expects that the circular functions should be reducible to rational functions.

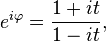

Geometrically, the construction goes like this: for any point (cos φ, sin φ) on the unit circle, draw the line passing through it and the point (−1,0). This point crosses the y-axis at some point y = t. One can show using simple geometry that t = tan(φ/2). The equation for the drawn line is y = (1 + x)t. The equation for the intersection of the line and circle is then a quadratic equation involving t. The two solutions to this equation are (−1, 0) and (cos φ, sin φ). This allows us to write the latter as rational functions of t (solutions are given below).

Note also that the parameter t represents the stereographic projection of the point (cos φ, sin φ) onto the y-axis with the center of projection at (−1,0). Thus, the tangent half-angle formulae give conversions between the stereographic coordinate t on the unit circle and the standard angular coordinate φ.

Then we have

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

and

|

|

By eliminating phi between the directly above and the initial definition of t, one arrives at the following useful relationship for the arctangent in terms of the natural logarithm

In calculus, the Weierstrass substitution is used to find antiderivatives of rational functions of sin(φ) and cos(φ). After setting

This implies that

and therefore

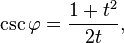

Hyperbolic identities

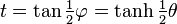

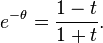

One can play an entirely analogous game with the hyperbolic functions. A point on (the right branch of) a hyperbola is given by (cosh θ, sinh θ). Projecting this onto y-axis from the center (−1, 0) gives the following:

with the identities

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

and

|

|

The use of this substitution for finding antiderivatives was introduced by Karl Weierstrass.

Finding θ in terms of t leads to following relationship between the hyperbolic arctangent and the natural logarithm:

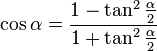

The Gudermannian function

Comparing the hyperbolic identities to the circular ones, one notices that they involve the same functions of t, just permuted. If we identify the parameter t in both cases we arrive at a relationship between the circular functions and the hyperbolic ones. That is, if

then

The function gd(θ) is called the Gudermannian function. The Gudermannian function gives a direct relationship between the circular functions and the hyperbolic ones that does not involve complex numbers. The above descriptions of the tangent half-angle formulae (projection the unit circle and standard hyperbola onto the y-axis) give a geometric interpretation of this function.

See also

External links

- Tangent Of Halved Angle at Planetmath

![\begin{align}

\tan\left(\frac{\eta}{2} \pm \frac{\theta}{2}\right) & = \frac{\sin\eta \pm \sin\theta}{\cos\eta + \cos\theta} = -\frac{\cos\eta - \cos\theta}{\sin\eta \mp \sin\theta}, \\[10pt]

\tan\left(\pm\frac{\theta}{2}\right) & = \frac{\pm\sin\theta}{1 + \cos\theta} = \frac{\pm\tan\theta}{\sec\theta + 1} = \frac{\pm 1}{\csc\theta + \cot\theta}, ~~~~(\eta = 0) \\[10pt]

\tan\left(\pm\frac{\theta}{2}\right) & = \frac{1-\cos\theta}{\pm\sin\theta} = \frac{\sec\theta-1}{\pm\tan\theta} = \pm(\csc\theta-\cot\theta), ~~~~(\eta=0) \\[10pt]

\tan\left(\frac{\pi}{4} \pm \frac{\theta}{2} \right) & = \frac{1 \pm \sin\theta}{\cos\theta} = \sec\theta \pm \tan\theta = \frac{\csc\theta \pm 1}{\cot\theta}, ~~~~(\eta=\frac{\pi}{2}) \\[10pt]

\tan\left(\frac{\pi}{4} \pm \frac{\theta}{2} \right) & = \frac{\cos\theta}{1 \mp \sin\theta} = \frac{1}{\sec\theta \mp \tan\theta} = \frac{\cot\theta}{\csc\theta \mp 1}, ~~~~(\eta=\frac{\pi}{2}) \\[10pt]

\frac{1 - \tan(\theta/2)}{1 + \tan(\theta/2)} & = \sqrt{\frac{1 - \sin\theta}{1 + \sin\theta}}.

\end{align}](../I/m/1dd3d00e13cde023e79df51d0845bc35.png)