Tamil language

| Tamil | |

|---|---|

| தமிழ் tamiḻ | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [t̪ɐmɨɻ] |

| Native to | India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, Réunion, Mauritius, Burma (moribund)[1] |

| Ethnicity | Tamil people |

Native speakers |

70 million (2007)[2] 8 million L2 speakers (no date)[3] |

|

Dravidian

| |

|

Tamil alphabet (Brahmic) Arwi Script (Abjad) Tamil Braille (Bharati) Vatteluttu (historical) | |

| Signed Tamil | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

ta |

| ISO 639-2 |

tam |

| ISO 639-3 |

Variously: tam – Modern Tamil oty – Old Tamil ptq – Pattapu Bhasha |

Linguist list |

oty Old Tamil |

| Glottolog |

tami1289 (Modern Tamil)[8]oldt1248 (Old Tamil)[9] |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Dravidian culture and history |

|---|

|

|

History

|

|

Culture

|

|

Language

|

|

Religion

|

|

Regions

|

|

People

|

| Portal:Dravidian civilizations |

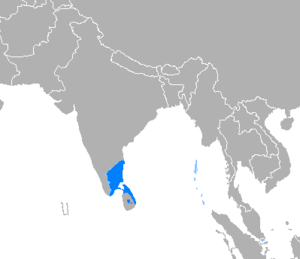

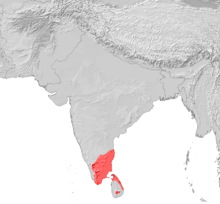

Tamil /ˈtæmɪl/ (தமிழ், tamiḻ, [t̪ɐmɨɻ] ?) also spelt Tamizh is a Dravidian language spoken predominantly by Tamil people of Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka. It has official status in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Puducherry and Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Tamil is also an official and national language of Sri Lanka[10] and one of the official languages of Singapore.[11] It is legalised as one of the languages of medium of education in Malaysia along with English, Malay and Mandarin.[12][13] It is also chiefly spoken in the states of Kerala, Puducherry and Andaman and Nicobar Islands as a secondary language and by minorities in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. It is one of the 22 scheduled languages of India and was the first Indian language to be declared a classical language by the Government of India in 2004. Tamil is also spoken by significant minorities in Malaysia, England, Mauritius, Canada,[14] South Africa,[15] Fiji,[16] Germany,[17] Philippines, United States, Netherlands, Indonesia,[18] Réunion and France as well as emigrant communities around the world.

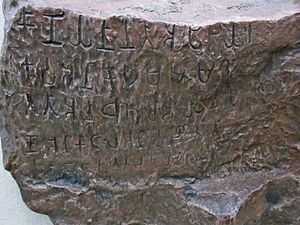

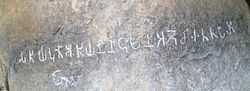

Tamil is one of the longest surviving classical languages in the world.[19][20] 2,200-year-old Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions have been found on Samanamalai It has been described as "the only language of contemporary India which is recognizably continuous with a classical past."[21] The variety and quality of classical Tamil literature has led to it being described as "one of the great classical traditions and literatures of the world".[22] Tamil literature has existed for over 2000 years.[23] The earliest period of Tamil literature, Sangam literature, is dated from ca. 300 BC – AD 300.[24][25] It has the oldest extant literature amongst other Dravidian languages.[19] The earliest epigraphic records found on rock edicts and hero stones date from around the 3rd century BC.[26][27] More than 55% of the epigraphical inscriptions (about 55,000) found by the Archaeological Survey of India are in the Tamil language.[28] Tamil language inscriptions written in Brahmi script have been discovered in Sri Lanka, and on trade goods in Thailand and Egypt.[29][30] The two earliest manuscripts from India,[31][32] acknowledged and registered by UNESCO Memory of the World register in 1997 and 2005, were in Tamil.[33]

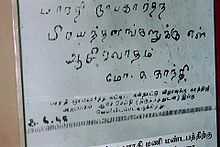

In 1578, Portuguese Christian Missionaries published a Tamil prayer book in old Tamil script named 'Thambiraan Vanakkam', thus making Tamil the first Indian language to be printed and published.[34] Tamil Lexicon, published by the University of Madras, is the first among the dictionaries published in any Indian language.[35] Tamil is used as a sacred language of Ayyavazhi and in Tamil Hindu traditions of Shaivism and Vaishnavism. According to a 2001 survey, there were 1,863 newspapers published in Tamil, of which 353 were dailies.[36]

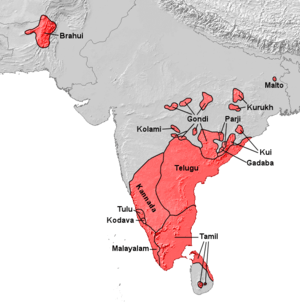

Classification

Tamil belongs to the southern branch of the Dravidian languages, a family of around 26 languages native to the Indian subcontinent.[37] It is also classified as being part of a Tamil language family, which alongside Tamil proper, also includes the languages of about 35 ethno-linguistic groups[38] such as the Irula and Yerukula languages (see SIL Ethnologue).

The closest major relative of Tamil is Malayalam; the two began diverging around the 9th century CE.[39] Although many of the differences between Tamil and Malayalam demonstrate a pre-historic split of the western dialect,[40] the process of separation into a distinct language, Malayalam, was not completed until sometime in the 13th or 14th century.[41]

Origin of Tamil in Hinduism

According to Hindu legend, Tamil, or in personification form Tamil Tāy (Mother Tamil), was created by Shiva. Shiva's Son, Lord Murugan, known as Lord Kartikeya in other Indian languages, and the sage Agastya brought it to people.[42]

History

Obv: Bust of king. Prakrit legend in the Brahmi script: "Siri Satakanisa Rano ... Vasithiputasa": "King Vasishtiputra Sri Satakarni"

Rev: Ujjain/Sātavāhana symbol left. Crescented six-arch chaitya hill right. River below. Early Tamil legend in the Tamil Brahmi script: "Arah(s)anaku Vah(s)itti makanaku Tiru H(S)atakani ko" – which means "The ruler, Vasitti's son, Highness Satakani" – -ko being the royal name suffix.[43][44][45][46]

According to linguists like Bhadriraju Krishnamurti, Tamil, as a Dravidian language, descends from Proto-Dravidian, a Proto-language. Linguistic reconstruction suggests that Proto-Dravidian was spoken around the third millennium BC, possibly in the region around the lower Godavari river basin in peninsular India. The material evidence suggests that the speakers of Proto-Dravidian were of the culture associated with the Neolithic complexes of South India.[47] The next phase in the reconstructed proto-history of Tamil is Proto-South Dravidian. The linguistic evidence suggests that Proto-South Dravidian was spoken around the middle of the second millennium BC, and that proto-Tamil emerged around the 3rd century BC. The earliest epigraphic attestations of Tamil are generally taken to have been written shortly thereafter.[48] Among Indian languages, Tamil has the most ancient non-Sanskritised Indian literature.[49] Scholars categorise the attested history of the language into three periods, Old Tamil (300 BC – AD 700), Middle Tamil (700–1600) and Modern Tamil (1600–present).[50] During a recent excavation at Quseir-al-Qadim, Egyptian pottery dating back to first century BC were discovered with ancient Tamil Brahmi inscriptions.[29]

Indians today might like to stereotype Gujaratis as the nation's most mercantile community, but at one point around 2,000 years ago, Tamil was the lingua franca of traders across the South East Asian seas.

“You get a sense of the role of early and medieval merchant guilds in the Deccan and Tamil Nadu and Kerala,” Guy said in a conversation with Scroll.in. “You know how common they are in India, but then you find their inscriptions in places like Sumatra and Thailand. It is astonishing how they got around. They were busy boys, travelling far and wide.” research started with a highly acclaimed exhibition curated last year at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. “Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, 5th to 8th Century” had 160 sculptures, gathered for the first time in such numbers, from museums and collections across India, Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam.[51]

Gold obsession

Around the first millennium, Tamil traders dominated the seas, inscriptions suggest, though they would later give way to Bengalis and Gujaratis from India and Arabic would eventually become the language of the region's merchants.Gold was more or less what Tamil merchants wanted at that time. Inscriptions suggest that the traders of South India were hoarders of precious metals, even as they paid their debts with textiles such as painted cotton kalamkaris and iron.“India retains the biggest private stores of gold in the world, and mostly in female hands,”. “It is true now and it always has been true.”India was notorious for demanding to settle its foreign debts in precious metals and owed everyone for their trade. Even the Romans were upset at having to buy muslins with precious metals.Making sure they always had the better deal, in South East Asia, Indian traders imported spices such as cloves and nutmeg in return for kalamkaris, painted cottons.[51]

Etymology

The earliest extant Tamil literary works and their commentaries celebrates the Pandiyan Kings for the organization of long-termed Tamil Sangams, which researched, developed and made amendments in Tamil language. Even though the name of the language which was developed by these Tamil Sangams is mentioned as Tamil, the exact period when the name "Tamil" came to be applied to the language is unclear, as is the precise etymology of the name. The earliest attested use of the name is found in Tholkappiyam, which is dated as early as 1st century BC.[52] Southworth suggests that the name comes from tam-miḻ > tam-iḻ 'self-speak', or 'one's own speech'.[53](see Southworth's derivation of Sanskrit term for "others" or Mleccha) Kamil Zvelebil suggests an etymology of tam-iḻ, with tam meaning "self" or "one's self", and "-iḻ" having the connotation of "unfolding sound". Alternatively, he suggests a derivation of tamiḻ < tam-iḻ < *tav-iḻ < *tak-iḻ, meaning in origin "the proper process (of speaking)".[54]

The Tamil Lexicon of University of Madras defines the word 'Tamil' as 'sweetness'.[55] S.V Subramanian suggests the meaning 'sweet sound' from 'tam'- sweet and 'il'- 'sound'.[56]

Old Tamil

The earliest records in Old Tamil are short inscriptions from between the 5th and 2nd century BCE in caves and on pottery. These inscriptions are written in a variant of the Brahmi script called Tamil Brahmi.[57] The earliest long text in Old Tamil is the Tolkāppiyam, an early work on Tamil grammar and poetics, whose oldest layers could be as old as the 1st century BC.[50] A large number of literary works in Old Tamil have also survived. These include a corpus of 2,381 poems collectively known as Sangam literature. These poems are usually dated to between the 1st and 5th centuries AD,[50][58] which makes them the oldest extant body of secular literature in India.[59] Other literary works in Old Tamil include Thirukural, Silappatikaram and Maṇimēkalai, and a number of ethical and didactic texts, written between the 5th and 8th centuries.[50]

Old Tamil preserved many features of Proto-Dravidian, including the inventory of consonants,[60] the syllable structure,[61] and various grammatical features.[62] Amongst these was the absence of a distinct present tense – like Proto-Dravidian, Old Tamil only had two tenses, the past and the "non-past". Old Tamil verbs also had a distinct negative conjugation (e.g. kāṇēṉ (காணேன்) "I do not see", kāṇōm (காணோம் "we do not see")[63] Nouns could take pronominal suffixes like verbs to express ideas: e.g. peṇṭirēm (பெண்டிரேம்) "we are women" formed from peṇṭir (பெண்டிர்) "women" and the first person plural marker -ēm (ஏம்).[64]

Despite the significant amount of grammatical and syntactical change between Old, Middle and Modern Tamil, Tamil demonstrates grammatical continuity across these stages: many characteristics of the later stages of the language have their roots in features of Old Tamil.[50]

Middle Tamil

The evolution of Old Tamil into Middle Tamil, which is generally taken to have been completed by the 8th century,[50] was characterised by a number of phonological and grammatical changes. In phonological terms, the most important shifts were the virtual disappearance of the aytam (ஃ), an old phoneme,[65] the coalescence of the alveolar and dental nasals,[66] and the transformation of the alveolar plosive into a rhotic.[67] In grammar, the most important change was the emergence of the present tense. The present tense evolved out of the verb kil (கில்), meaning "to be possible" or "to befall". In Old Tamil, this verb was used as an aspect marker to indicate that an action was micro-durative, non-sustained or non-lasting, usually in combination with a time marker such as ṉ (ன்). In Middle Tamil, this usage evolved into a present tense marker – kiṉṟa (கின்ற) – which combined the old aspect and time markers.[68]

From the period of the Pallava dynasty onwards, a number of Sanskrit loan-words entered Tamil, particularly in relation to political, religious and philosophical concepts.[69] Sanskrit also influenced Tamil grammar, in the increased use of cases and in declined nouns becoming adjuncts of verbs,[70] and phonology. The forms of writing in Tamil have developed through years.[71] The Tamil script also changed in the period of Middle Tamil. Tamil Brahmi and Vaṭṭeḻuttu, into which it evolved, were the main scripts used in Old Tamil inscriptions. From the 8th century onwards, however, the Pallavas began using a new script, derived from the Pallava Grantha script which was used to write Sanskrit, which eventually replaced Vaṭṭeḻuttu.[72]

Middle Tamil is attested in a large number of inscriptions, and in a significant body of secular and religious literature.[73] These include the religious poems and songs of the Bhakthi poets, such as the Tēvāram verses on Shaivism and Nālāyira Tivya Pirapantam on Vaishnavism,[74] and adaptations of religious legends such as the 12th century Tamil Ramayana composed by Kamban and the story of 63 shaivite devotees known as Periyapurāṇam.[75] Iraiyaṉār Akapporuḷ, an early treatise on love poetics, and Naṉṉūl, a 12th-century grammar that became the standard grammar of literary Tamil, are also from the Middle Tamil period.[76] There is a famous saying

| “ | " திருவாசகத்துக்கு உருகார் ஒரு வாசகத்திற்கும் உருகார்" | ” |

translating to "He whose heart is not melted by Thiruvasagam cannot be melted by any vasagam(saying)".[77] The Thiruvasagam is composed by Manikkavasagar

Modern Tamil

The Nannul remains the standard normative grammar for modern literary Tamil, which therefore continues to be based on Middle Tamil of the 13th century rather than on Modern Tamil.[78] Colloquial spoken Tamil, in contrast, shows a number of changes. The negative conjugation of verbs, for example, has fallen out of use in Modern Tamil[79] – negation is, instead, expressed either morphologically or syntactically.[80] Modern spoken Tamil also shows a number of sound changes, in particular, a tendency to lower high vowels in initial and medial positions,[81] and the disappearance of vowels between plosives and between a plosive and rhotic.[82]

Contact with European languages also affected both written and spoken Tamil. Changes in written Tamil include the use of European-style punctuation and the use of consonant clusters that were not permitted in Middle Tamil. The syntax of written Tamil has also changed, with the introduction of new aspectual auxiliaries and more complex sentence structures, and with the emergence of a more rigid word order that resembles the syntactic argument structure of English.[83] Simultaneously, a strong strain of linguistic purism emerged in the early 20th century, culminating in the Pure Tamil Movement which called for removal of all Sanskritic and other foreign elements from Tamil.[84] It received some support from Dravidian parties.[85] This led to the replacement of a significant number of Sanskrit loanwords by Tamil equivalents, though many others remain.[86]

Geographic distribution

Tamil is the first language of the majority of the people residing in Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, in India and Northern Province, Eastern Province, in Sri Lanka. The language is also spoken among small minority groups in other states of India which include Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Maharashtra and in certain regions of Sri Lanka such as Colombo and the hill country. Tamil or dialects of it were used widely in the state of Kerala as the major language of administration, literature and common usage until the 12th century AD. Tamil was also used widely in inscriptions found in southern Andhra Pradesh districts of Chittoor and Nellore until the 12th century AD.[87] Tamil was also used for inscriptions from the 10th through 14th centuries in southern Karnataka districts such as Kolar, Mysore, Mandya and Bangalore.[88]

There are currently sizeable Tamil-speaking populations descended from colonial-era migrants in Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Mauritius, South Africa, Indonesia,[89] Thailand,[90] Burma, and Vietnam. A large community of Tamil speakers exists in Karachi, Pakistan, which includes Tamil-speaking Hindus[91][92] as well as Christians and Muslims – including some Tamil-speaking Muslim refugees from Sri Lanka.[93] Many in Réunion, Guyana, Fiji, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago have Tamil origins,[94] but only a small number speak the language. In Reunion where the Tamil language was forbidden to be learnt and used in public space by France it is now being relearnt by students and adults.[95] It is also used by groups of migrants from Sri Lanka and India, Canada (especially Toronto), United States (especially New Jersey and New York City), Australia, many Middle Eastern countries, and some Western European countries.

Legal status

Tamil is the official language of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and one of the 22 languages under schedule 8 of the constitution of India. It is also one of the official languages of the union territory of Puducherry and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[96][97] Tamil is also one of the official languages of Singapore. Tamil is one of the official and national language of Sri Lanka, along with Sinhala.[98] It was once given nominal official status in the state of Haryana, purportedly as a rebuff to Punjab, though there was no attested Tamil-speaking population in the state, and was later replaced by Punjabi, in 2010.[99] In Malaysia, 543 primary education government schools are available fully in Tamil medium.[100] The establishments of Tamil medium schools have been currently in process in Myanmar to provide education completely in Tamil language by the Tamils who settled there 200 years ago.[1] Tamil language is taught in Canada and South Africa for the local Tamil minority populations. In Ontario, Canada, the month of January has been declared "Tamil Heritage Month" per legislation.

In addition, with the creation in October 2004 of a legal status for classical languages by the Government of India and following a political campaign supported by several Tamil associations,[101][102] Tamil became the first legally recognised Classical language of India. The recognition was announced by the then President of India, Abdul Kalam, in a joint sitting of both houses of the Indian Parliament on 6 June 2004.[103][104][105]

Dialects

Region-specific variations

The socio-linguistic situation of Tamil is characterised by diglossia: there are two separate registers varying by social status, a high register and a low one.[106][107] Tamil dialects are primarily differentiated from each other by the fact that they have undergone different phonological changes and sound shifts in evolving from Old Tamil. For example, the word for "here"—iṅku in Centamil (the classic variety)—has evolved into iṅkū in the Kongu dialect of Coimbatore, inga in the dialect of Thanjavur, and iṅkai in some dialects of Sri Lanka. Old Tamil's iṅkaṇ (where kaṇ means place) is the source of iṅkane in the dialect of Tirunelveli, Old Tamil iṅkaṭṭu is the source of iṅkuṭṭu in the dialect of Madurai, and iṅkaṭe in various northern dialects. Even now, in the Coimbatore area, it is common to hear "akkaṭṭa" meaning "that place". Although Tamil dialects do not differ significantly in their vocabulary, there are a few exceptions. The dialects spoken in Sri Lanka retain many words and grammatical forms that are not in everyday use in India,[50][108] and use many other words slightly differently.[109] The various Tamil dialects include Central Tamil dialect, Kongu Tamil, Madras Bashai, Madurai Tamil, Nellai Tamil, kumari Tamil in India and Batticaloa Tamil dialect, Jaffna Tamil dialect, Negombo Tamil dialect in Sri Lanka. Sankethi dialect in Karnataka has been heavily influenced by Kannada.

Loanword variations

The dialect of the district of Palakkad in Kerala has a large number of Malayalam loanwords, has been influenced by Malayalam's syntax and also has a distinctive Malayalam accent. Similarly, Tamil spoken in Kanyakumari District has more unique words and phonetic style than Tamil spoken at other parts of Tamil Nadu. The words and phonetics are so different that a person from Kanyakumari district is easily identifiable by their spoken Tamil. Hebbar and Mandyam dialects, spoken by groups of Tamil Vaishnavites who migrated to Karnataka in the 11th century, retain many features of the Vaishnava paribasai, a special form of Tamil developed in the 9th and 10th centuries that reflect Vaishnavite religious and spiritual values.[110] Several castes have their own sociolects which most members of that caste traditionally used regardless of where they come from. It is often possible to identify a person's caste by their speech.[111] Tamil in Sri Lanka incorporates loan words from Portuguese, Dutch, and English.

Spoken and literary variants

In addition to its various dialects, Tamil exhibits different forms: a classical literary style modelled on the ancient language (sankattamiḻ), a modern literary and formal style (centamiḻ), and a modern colloquial form (koṭuntamiḻ). These styles shade into each other, forming a stylistic continuum. For example, it is possible to write centamiḻ with a vocabulary drawn from caṅkattamiḻ, or to use forms associated with one of the other variants while speaking koṭuntamiḻ.[112]

In modern times, centamiḻ is generally used in formal writing and speech. For instance, it is the language of textbooks, of much of Tamil literature and of public speaking and debate. In recent times, however, koṭuntamiḻ has been making inroads into areas that have traditionally been considered the province of centamiḻ. Most contemporary cinema, theatre and popular entertainment on television and radio, for example, is in koṭuntamiḻ, and many politicians use it to bring themselves closer to their audience. The increasing use of koṭuntamiḻ in modern times has led to the emergence of unofficial ‘standard' spoken dialects. In India, the ‘standard' koṭuntamiḻ, rather than on any one dialect,[113] but has been significantly influenced by the dialects of Thanjavur and Madurai. In Sri Lanka, the standard is based on the dialect of Jaffna.

Writing system

After Tamil Brahmi fell out of use, Tamil was written using a script called the vaṭṭeḻuttu amongst others such as Grantha and Pallava script. The current Tamil script consists of 12 vowels, 18 consonants and one special character, the āytam. The vowels and consonants combine to form 216 compound characters, giving a total of 247 characters (12 + 18 + 1 + (12 x 18)). All consonants have an inherent vowel a, as with other Indic scripts. This inherent vowel is removed by adding a tittle called a puḷḷi, to the consonantal sign. For example, ன is ṉa (with the inherent a) and ன் is ṉ (without a vowel). Many Indic scripts have a similar sign, generically called virama, but the Tamil script is somewhat different in that it nearly always uses a visible puḷḷi to indicate a dead consonant (a consonant without a vowel). In other Indic scripts, it is generally preferred to use a ligature or a half form to write a syllable or a cluster containing a dead consonant, although writing it with a visible virama is also possible. The Tamil script does not differentiate voiced and unvoiced plosives. Instead, plosives are articulated with voice depending on their position in a word, in accordance with the rules of Tamil phonology.

In addition to the standard characters, six characters taken from the Grantha script, which was used in the Tamil region to write Sanskrit, are sometimes used to represent sounds not native to Tamil, that is, words adopted from Sanskrit, Prakrit and other languages. The traditional system prescribed by classical grammars for writing loan-words, which involves respelling them in accordance with Tamil phonology, remains, but is not always consistently applied.[114]

Phonology

Tamil phonology is characterised by the presence of retroflex consonants and multiple rhotics. Tamil does not distinguish phonologically between voiced and unvoiced consonants; phonetically, voice is assigned depending on a consonant's position in a word.[115] Tamil phonology permits few consonant clusters, which can never be word initial. Native grammarians classify Tamil phonemes into vowels, consonants, and a "secondary character", the āytam.

Vowels

Tamil has five pure vowel sounds /ɐ/, /e/, /i/, /o/ and /u/. Each vowel has a long and short version. There are two diphthongs, /aːɪ/ and /aːʊ/, and three "shortened" vowels.

Long vowels are about twice as long as short vowels. The diphthongs are usually pronounced about 1.5 times as long as short vowels. Most grammatical texts place them with long vowels.

| Short | Long | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | Front | Central | Back | |

| Close | i | u | iː | uː | ||

| இ | உ | ஈ | ஊ | |||

| Mid | e | o | eː | oː | ||

| எ | ஒ | ஏ | ஓ | |||

| Open | ɐ | (aːɪ) | äː | (aːʊ) | ||

| அ | ஐ | ஆ | ஒள | |||

Consonants

Tamil consonants are presented as hard, soft and medial in some grammars which roughly corresponds to plosives, approximants and nasals. Unlike most Indian languages, Tamil does not distinguish aspirated and unaspirated consonants. In addition, the voicing of plosives is governed by strict rules in centamiḻ. Plosives are unvoiced if they occur word-initially or doubled. Elsewhere they are voiced, with a few becoming fricatives intervocalically. Nasals and approximants are always voiced.[116]

Tamil is characterised by its use of more than one type of coronal consonants: like many of the other languages of India, it contains a series of retroflex consonants. Notably, the Tamil retroflex series includes the retroflex approximant /ɻ/ (ழ) (example Tamil; often transcribed 'zh'), which is absent in the Indo-Aryan languages. Among the other Dravidian languages, the retroflex approximant also occurs in Malayalam (for example in 'Kozhikode'), disappeared from spoken Kannada around 1000 AD (although the character is still written, and exists in Unicode), and was never present in Telugu. In many dialects of colloquial Tamil, this consonant is seen as disappearing and shifting to the alveolar lateral approximant /l/.[117] Dental and alveolar consonants also historically contrasted with each other, a typically Dravidian trait not found in the neighbouring Indo-Aryan languages. While this distinction can still be seen in the written language, it has been largely lost in colloquial spoken Tamil, and even in literary usage the letters ந (dental) and ன (alveolar) may be seen as allophonic.[118] Likewise, the historical alveolar stop has transformed into a trill consonant in many modern dialects.

A chart of the Tamil consonant phonemes in the International Phonetic Alphabet follows:[108]

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p (b) | t̪ (d̪) | t (d) | ʈ (ɖ) | t͡ɕ (d͡ʑ) | k (ɡ) |

| ப | த | ற | ட | ச | க | |

| Nasals | m | n̪ | n | ɳ | ȵ | ŋ |

| ம | ந | ன | ண | ஞ | ங | |

| Tap | ɽ | |||||

| ர | ||||||

| Central approximants | v | ɻ | j | |||

| வ | ழ | ய | ||||

| Lateral approximants | l̪ | ɭ | ||||

| ல | ள |

Sounds in brackets are voiced allophones. They are written the same as the voiceless allophones, as voicing is determined by context. The sounds /f/ and /ʂ/ are peripheral to the phonology of Tamil, being found only in loanwords and frequently replaced by native sounds. There are well-defined rules for elision in Tamil categorised into classes based on the phoneme which undergoes elision.

Āytam

Classical Tamil also had a phoneme called the Āytam, written as ‘ஃ'. Tamil grammarians of the time classified it as a dependent phoneme (or restricted phoneme[119]) (cārpeḻuttu), but it is very rare in modern Tamil. The rules of pronunciation given in the Tolkāppiyam, a text on the grammar of Classical Tamil, suggest that the āytam could have glottalised the sounds it was combined with. It has also been suggested that the āytam was used to represent the voiced implosive (or closing part or the first half) of geminated voiced plosives inside a word.[120] The Āytam, in modern Tamil, is also used to convert p to f when writing English words using the Tamil script.

Numerals and symbols

Apart from the usual numerals, Tamil also has numerals for 10, 100 and 1000. Symbols for day, month, year, debit, credit, as above, rupee, and numeral are present as well.Tamil also uses several historical fractional signs.

| zero | one | two | three | four | five | six | seven | eight | nine | ten | hundred | thousand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ௦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ | ௰ | ௱ | ௲ |

| day | month | year | debit | credit | as above | rupee | numeral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ௳ | ௴ | ௵ | ௶ | ௷ | ௸ | ௹ | ௺ |

Grammar

Tamil employs agglutinative grammar, where suffixes are used to mark noun class, number, and case, verb tense and other grammatical categories. Tamil's standard metalinguistic terminology and scholarly vocabulary is itself Tamil, as opposed to the Sanskrit that is standard for most Aryan languages.[121][122]

Much of Tamil grammar is extensively described in the oldest known grammar book for Tamil, the Tolkāppiyam. Modern Tamil writing is largely based on the 13th century grammar Naṉṉūl which restated and clarified the rules of the Tolkāppiyam, with some modifications. Traditional Tamil grammar consists of five parts, namely eḻuttu, sol, poruḷ, yāppu, aṇi. Of these, the last two are mostly applied in poetry.[123]

Tamil words consist of a lexical root to which one or more affixes are attached. Most Tamil affixes are suffixes. Tamil suffixes can be derivational suffixes, which either change the part of speech of the word or its meaning, or inflectional suffixes, which mark categories such as person, number, mood, tense, etc. There is no absolute limit on the length and extent of agglutination, which can lead to long words with a large number of suffixes.

Morphology

Tamil nouns (and pronouns) are classified into two super-classes (tiṇai)—the "rational" (uyartiṇai), and the "irrational" (akṟiṇai)—which include a total of five classes (pāl, which literally means ‘gender'). Humans and deities are classified as "rational", and all other nouns (animals, objects, abstract nouns) are classified as irrational. The "rational" nouns and pronouns belong to one of three classes (pāl)—masculine singular, feminine singular, and rational plural. The "irrational" nouns and pronouns belong to one of two classes: irrational singular and irrational plural. The pāl is often indicated through suffixes. The plural form for rational nouns may be used as an honorific, gender-neutral, singular form.[124]

Suffixes are used to perform the functions of cases or postpositions. Traditional grammarians tried to group the various suffixes into eight cases corresponding to the cases used in Sanskrit. These were the nominative, accusative, dative, sociative, genitive, instrumental, locative, and ablative. Modern grammarians argue that this classification is artificial,[125] and that Tamil usage is best understood if each suffix or combination of suffixes is seen as marking a separate case.[113] Tamil nouns can take one of four prefixes, i, a, u, and e which are functionally equivalent to the demonstratives in English.

Tamil verbs are also inflected through the use of suffixes. A typical Tamil verb form will have a number of suffixes, which show person, number, mood, tense, and voice.

- Person and number are indicated by suffixing the oblique case of the relevant pronoun. The suffixes to indicate tenses and voice are formed from grammatical particles, which are added to the stem.

- Tamil has two voices. The first indicates that the subject of the sentence undergoes or is the object of the action named by the verb stem, and the second indicates that the subject of the sentence directs the action referred to by the verb stem.

- Tamil has three simple tenses—past, present, and future—indicated by the suffixes, as well as a series of perfects indicated by compound suffixes. Mood is implicit in Tamil, and is normally reflected by the same morphemes which mark tense categories. Tamil verbs also mark evidentiality, through the addition of the hearsay clitic ām.[126]

Traditional grammars of Tamil do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, including both of them under the category uriccol, although modern grammarians tend to distinguish between them on morphological and syntactical grounds.[127] Tamil has a large number of ideophones that act as adverbs indicating the way the object in a given state "says" or "sounds".[128]

Tamil does not have articles. Definiteness and indefiniteness are either indicated by special grammatical devices, such as using the number "one" as an indefinite article, or by the context.[129] In the first person plural, Tamil makes a distinction between inclusive pronouns நாம் nām (we), நமது namatu (our) that include the addressee and exclusive pronouns நாங்கள் nāṅkaḷ (we), எமது ematu (our) that do not.[129]

Syntax

Tamil is a consistently head-final language. The verb comes at the end of the clause, with a typical word order of subject–object–verb (SOV).[130][131] However, word order in Tamil is also flexible, so that surface permutations of the SOV order are possible with different pragmatic effects. Tamil has postpositions rather than prepositions. Demonstratives and modifiers precede the noun within the noun phrase. Subordinate clauses precede the verb of the matrix clause.

Tamil is a null-subject language. Not all Tamil sentences have subjects, verbs, and objects. It is possible to construct grammatically valid and meaningful sentences which lack one or more of the three. For example, a sentence may only have a verb—such as muṭintuviṭṭatu ("completed")—or only a subject and object, without a verb such as atu eṉ vīṭu ("That [is] my house"). Tamil does not have a copula (a linking verb equivalent to the word is). The word is included in the translations only to convey the meaning more easily.

Vocabulary

The vocabulary of Tamil is mainly Dravidian. A strong sense of linguistic purism is found in Modern Tamil,[132] which opposes the use of foreign loanwords.[133] Nonetheless, a number of words used in classical and modern Tamil are loanwords from the languages of neighbouring groups, or with whom the Tamils had trading links, including Munda (for example, tavaḷai "frog" from Munda tabeg), Malay (e.g. cavvarici "sago" from Malay sāgu), Chinese (for example, campān "skiff" from Chinese san-pan) and Greek (for example, ora from Greek ὥρα). In more modern times, Tamil has imported words from Urdu and Marathi, reflecting groups that have influenced the Tamil area at various points of time, and from neighbouring languages such as Telugu, Kannada, and Sinhala. During the modern period, words have also been adapted from European languages, such as Portuguese, French, and English.[134]

The strongest impact of purism in Tamil has been on words taken from Sanskrit. During its history, Tamil, along with other Dravidian languages like Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam etc., was influenced by Sanskrit in terms of vocabulary, grammar and literary styles,[135][136][137][138] reflecting the increased trend of Sanskritisation in the Tamil country.[139] Tamil vocabulary never became quite as heavily Sanskritised as that of the other Dravidian languages, and unlike in those languages, it was and remains possible to express complex ideas (including in science, art, religion and law) without the use of Sanskrit loan words.[140][141][142] In addition, Sanskritisation was actively resisted by a number of authors of the late medieval period,[143] culminating in the 20th century in a movement called taṉit tamiḻ iyakkam (meaning "pure Tamil movement"), led by Parithimaar Kalaignar and Maraimalai Adigal, which sought to remove the accumulated influence of Sanskrit on Tamil.[144] As a result of this, Tamil in formal documents, literature and public speeches has seen a marked decline in the use Sanskrit loan words in the past few decades,[145] under some estimates having fallen from 40–50% to about 20%.[86] As a result, the Prakrit and Sanskrit loan words used in modern Tamil are, unlike in some other Dravidian languages, restricted mainly to some spiritual terminology and abstract nouns.[146]

In the 20th century, institutions and learned bodies have, with government support, generated technical dictionaries for Tamil containing neologisms and words derived from Tamil roots to replace loan words from English and other languages.[84]

Influence

Words of Tamil origin occur in other languages. A notable example of a word in worldwide use with Dravidian (not specifically Tamil) etymology is orange, via Sanskrit nāraṅga from a Dravidian predecessor of Tamil nartankāy "fragrant fruit". Anaconda is word of Tamil origin anai-kondra meaning elephant killer[147] Examples in English include cheroot (churuṭṭu meaning "rolled up"),[148] mango (from mangai),[148] mulligatawny (from miḷaku taṉṉir, "pepper water"), pariah (from paraiyan), curry (from kari),[149] and catamaran (from kaṭṭu maram, "bundled logs").[148]

See also

- Kural Peedam Award

- List of countries where Tamil is an official language

- List of languages by first written accounts

- Siddha Medicine

- Tamil diaspora

- Tamil Keyboard

- Tamil population by cities

- Tamil population by nation

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Natarajan, Swaminathan (6 March 2014) Myanmar's Tamils seek to protect their identity. BBC

- ↑ Nationalencyklopedin "Världens 100 största språk 2007" The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007

- ↑ Tamil language at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- ↑ "Official languages of Tamil Nadu", Tamil Nadu Government, retrieved 1 May 2007

- ↑ Official languages, UNESCO, retrieved 10 May 2007

- ↑ "Official languages of Srilanka", State department, US, retrieved 1 May 2007

- ↑ "Official languages and national language", Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Government of Singapore), retrieved 22 April 2008

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Modern Tamil". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Old Tamil". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Department of Official Languages. Government of Srilanka

- ↑ Republic of Singapore Independence Act, s.7. Republic of Singapore

- ↑ Tamil Schools. Indianmalaysian.com. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ Ghazali, Kamila (2010). UN Chronicle – National Identity and Minority Languages. United Nations.

- ↑ "Toronto's Tamil-Canadian community gears up to host new refugees", The Star, 14 August 2010

- ↑ Subramaniyan, S. (December 1998) Tamil Language and Murukan Worship in South Africa. First International Conference Seminar on Skanda-Murukan

- ↑ "Ethnologue report for language code tam", Ethnologue: Languages of the World, retrieved 31 July 2007

- ↑ Baumann, Martin. Immigrant Hinduism in Germany: Tamils from Sri Lanka and Their Temples. The Pluralism Project, Harvard University

- ↑ Tamil Indonesians. tamilnation.co

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Stein, B. (1977). "Circulation and the Historical Geography of Tamil Country". The Journal of Asian Studies 37: 7. doi:10.2307/2053325. JSTOR 2053325.

- ↑ Steever 1998, pp. 6–9

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamil (1973), The Smile of Murugan, BRILL, pp. 11–12, ISBN 978-90-04-03591-1

- ↑ Hart, George L. Statement on the Status of Tamil as a Classical Language, University of California Berkeley Department of South Asian Studies – Tamil

- ↑ Zvelebil 1992, p. 12: "...the most acceptable periodisation which has so far been suggested for the development of Tamil writing seems to me to be that of A Chidambaranatha Chettiar (1907–1967): 1. Sangam Literature – 200BC to AD 200; 2. Post Sangam literature – AD 200 – AD 600; 3. Early Medieval literature – AD 600 to AD 1200; 4. Later Medieval literature – AD 1200 to AD 1800; 5. Pre-Modern literature – AD 1800 to 1900"

- ↑ Definitive Editions of Ancient Tamil Works. Classical Tamil, Government of India

- ↑ Abraham, S. A. (2003). "Chera, Chola, Pandya: Using Archaeological Evidence to Identify the Tamil Kingdoms of Early Historic South India". Asian Perspectives 42 (2): 207. doi:10.1353/asi.2003.0031.

- ↑ Maloney, C. (1970). "The Beginnings of Civilization in South India". The Journal of Asian Studies 29 (3): 603. doi:10.2307/2943246. JSTOR 2943246. at p. 610

- ↑ Subramaniam, T.S (29 August 2011), "Palani excavation triggers fresh debate", The Hindu (Chennai, India)

- ↑ "Students get glimpse of heritage", The Hindu (Chennai, India), 22 November 2005

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Tamil Brahmi script in Egypt". The Hindu. 21 November 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Mahadevan, Iravatham (24 June 2010). "An epigraphic perspective on the antiquity of Tamil". The Hindu (Chennai, India).

- ↑ The I.A.S. Tamil Medical Manuscript Collection, UNESCO, retrieved 13 September 2012

- ↑ Saiva Manuscript in Pondicherry, UNESCO, retrieved 13 September 2012

- ↑ Memory of the World Register: India, UNESCO, retrieved 13 September 2012

- ↑ Karthik Madhavan. "Tamil saw its first book in 1578". The Hindu.

- ↑ Kolappan, B. (22 June 2014). "Delay, howlers in Tamil Lexicon embarrass scholars". The Hindu (Chennai). Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ India 2001: A Reference Annual 2001. Compiled and edited by Research, Reference and Training Division, Publications Division, New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, p. 19

- ↑ Perumal, A. K. (2005) Manorama Yearbook (Tamil), pp. 302–318.

- ↑ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. 2010. p. 297.

- ↑ Menon, A. G. (2009). "Some observations on the sub-group Tamil-Malayalam: Differential realizations of the cluster * ṉt". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 53: 87. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00021285.

- ↑ Andronov 1970, p. 21

- ↑ Sumathi Ramaswamy, Passions of the Tongue: Language Devotion in Tamil India, 1891–1970, p. 87, 1997

- ↑ Nagaswamy, N (1995), Roman Karur, Brahad Prakashan, OCLC 191007985

- ↑ Mahadevan 2003, pp. 199–205

- ↑ Panneerselvam, R (1969), "Further light on the bilingual coin of the Sātavāhanas", Indo-Iranian Journal 4 (11): 281–288, doi:10.1163/000000069790078428

- ↑ Yandel, Keith (2000), Religion and Public Culture: Encounters and Identities in Modern South India, Routledge Curzon, p. 235, ISBN 0-7007-1101-5

- ↑ Southworth 2005, pp. 249–250

- ↑ Southworth 2005, pp. 250–251

- ↑ Sivathamby, K (1974). "Early South Indian Society and Economy: The Tinai Concept". Social Scientist 3 (5): 20–37. JSTOR 3516448.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 50.6 Lehmann 1998, pp. 75–76

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "Scroll.in – News. Politics. Culture.". scroll.in.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1992, p. x

- ↑ Southworth 1998, pp. 129–132

- ↑ Zvelebil 1992, p. ix–xvi

- ↑ Tamil lexicon, Madras: University of Madras, 1924–36, retrieved 26 February 2012. (Online edition at the University of Chicago)

- ↑ Subramanian, S.V (1980), Heritage of Tamils; Language and Grammar, International Institute of Tamil Studies, pp. 7–12

- ↑ Mahadevan 2003, pp. 90–95

- ↑ The dating of Sangam literature and the identification of its language with Old Tamil have recently been questioned by Herman Tieken who argues that the works are better understood as 9th century Pāṇṭiyan dynasty compositions, deliberately written in an archaising style to make them seem older than they were (Tieken 2001). Tieken's dating has, however, been criticised by reviewers of his work. See e.g.

- Hart, G.; Tieken, H. (2004). "Kāvya in South India: Old Tamil Caṅkam Poetry". Journal of the American Oriental Society 124: 180. doi:10.2307/4132191. JSTOR 4132191.

- Ferro-Luzzi, G. E.; Tieken, H. (2001). "Kavya in South India: Old Tamil Cankam Poetry". Asian Folklore Studies 60 (2): 373. doi:10.2307/1179075. JSTOR 1179075.

- Monius, A. E.; Dubianskii, A. M.; Tieken, H. (2002). "Ritual and Mythological Sources of the Early Tamil Poetry". The Journal of Asian Studies 61 (4): 1404. doi:10.2307/3096501. JSTOR 3096501.

- Wilden, E. V. A. (2003). "Towards an Internal Chronology of Old Tamil Cankam Literature or How to Trace the Laws of a Poetic Universe". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens 1 (16): 105. doi:10.1553/wzksXLVIs105.

- ↑ Tharu & Lalita 1991, p. 70

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, p. 53

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, p. 92

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 182–193

- ↑ Steever 1998, p. 24

- ↑ Lehmann 1998, p. 80

- ↑ Kuiper 1958, p. 194

- ↑ Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 132–133

- ↑ Kuiper 1958, pp. 213–215

- ↑ Rajam, V. S. (1985). "The Duration of an Action-Real or Aspectual? The Evolution of the Present Tense in Tamil". Journal of the American Oriental Society 105 (2): 277. doi:10.2307/601707. JSTOR 601707. at pp. 284–285

- ↑ Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 173–174

- ↑ Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 153–154

- ↑ Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 145–146

- ↑ Mahadevan 2003, pp. 208–213

- ↑ Meenakshisundaran 1965, p. 119

- ↑ Varadarajan 1988

- ↑ Varadarajan 1988, pp. 155–157

- ↑ Zvelebil 1992, p. 227

- ↑ Macdonell 1994, p. 219

- ↑ Shapiro & Schiffman 1983, p. 2

- ↑ Annamalai & Steever 1998, p. 100

- ↑ Steever 2005, pp. 107–8

- ↑ Meenakshisundaran 1965, p. 125

- ↑ Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 122–123

- ↑ Kandiah, T. (1978). "Standard Language and Socio-Historical Parameters: Standard Lankan Tamil". International Journal of the Sociology of Language 1978 (16). doi:10.1515/ijsl.1978.16.59. at pp. 65–69

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Ramaswamy 1997

- ↑ Ramaswamy 1997: "Dravidianism, too, lent its support to the contestatory classicist project, motivated principally by the political imperative of countering (Sanskritic) Indian nationalism... It was not until the DMK came to power in 1967 that such demands were fulfilled, and the pure Tamil cause received a boost, although purification efforts are not particularly high on the agenda of either the Dravidian movement or the Dravidianist idiom of tamiḻppaṟṟu."

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Krishnamurti 2003, p. 480

- ↑ Talbot 2001, pp. 27–37

- ↑ Murthy et al. 1990, pp. 85–106

- ↑ Ramstedt 2004, p. 243

- ↑ 2008 Kesavapany, p. 60

- ↑ Shahbazi, Ammar (20 March 2012), "Strangers to Their Roots and Those Around Them", The News (Pakistan)

- ↑ Sunny, Sanjesh (21 September 2010) Tamil Hindus in Karachi. Pakistan Hindu Post

- ↑ Raman, B. (15 July 2002) Osama's shadow on Sri Lanka?. The Hindu Business Line

- ↑ McMahon, Suzanne, Overview of the South Asian Diaspora, University of California, Berkeley, retrieved 23 April 2008

- ↑ Ghasarian, Christian, Indentured immigration and social accommodation in La Réunion, University of California, Berkeley, retrieved 8 January 2010

- ↑ Ramamoorthy, L (February 2004), Multilingualism and Second Language Acquisition and Learning in Pondicherry, Language in India, retrieved 16 August 2007

- ↑ Sunwani, Vijay K (February 2007), Amazing Andamans and North-East India: A Panoramic View of States, Societies and Cultures (PDF), Language in India, retrieved 16 August 2007

- ↑ http://www.languagesdept.gov.lk/, retrieved 13 September 2012

- ↑ Bharadwaj, Ajay (7 March 2010) Punjabi edges out Tamil in Haryana. DNA India

- ↑ Language Shift in the Tamil Communities of Malaysia and Singapore: the Paradox of Egalitarian Language Policy, Ccat.sas.upenn.edu, retrieved 13 September 2012

- ↑ Dutta, Sujan (28 September 2004), "Classic case of politics of language", The Telegraph (Kolkata, India), retrieved 20 April 2007,

Members of the committee felt that the pressure was being brought on it because of the compulsions of the Congress and the UPA government to appease its ally, M. Karunanidhi's DMK.

- ↑ Vasan, S. S. (October 2004) Recognising a classic. The Hindu

- ↑ Thirumalai, MS (November 2004), "Tradition, Modernity and Impact of Globalization – Whither Will Tamil Go?", Language in India 4, retrieved 17 November 2007

- ↑ India sets up classical languages. BBC. 17 August 2004.

- ↑ "Sanskrit to be declared classical language". The Hindu. 28 October 2005.

- ↑ Arokianathan, S. Writing and Diglossic: A Case Study of Tamil Radio Plays. ciil-ebooks.net

- ↑ Steever, S. B.; Britto, F. (1988). "Diglossia: A Study of the Theory, with Application to Tamil". Language 64: 152. doi:10.2307/414796. JSTOR 414796.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Annamalai & Steever 1998, pp. 100–28

- ↑ Zvelebil, K. (1966). "Some features of Ceylon Tamil". Indo-Iranian Journal 9 (2): 113. doi:10.1163/000000066790086440.

- ↑ Thiru. Mu (1978). Kovintācāriyar, Vāḻaiyaṭi vāḻai Lifco, Madras, pp. 26–39.

- ↑ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2013) "Tamil dialects" in Tamil language. Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ↑ Schiffman, Harold (1997). "Diglossia as a Sociolinguistic Situation", in Florian Coulmas (ed.), The Handbook of Sociolinguistics. London: Basil Blackwell, Ltd. pp. 205 ff.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 Schiffman, Harold (1998), "Standardization or restandardization: The case for 'Standard' Spoken Tamil", Language in Society 27 (3): 359–385, doi:10.1017/S0047404598003030.

- ↑ Fowler, Murray (1954). "The Segmental Phonemes of Sanskritized Tamil". Language (Linguistic Society of America) 30 (3): 360–367. doi:10.2307/410134. JSTOR 410134. at p. 360.

- ↑ Schiffman, Harold F.; Arokianathan, S. (1986), "Diglossic variation in Tamil film and fiction", in Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju; Masica, Colin P., South Asian languages: structure, convergence, and diglossia, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, p. 371, ISBN 81-208-0033-8

- ↑ See e.g. the pronunciation guidelines in G.U. Pope (1868). A Tamil hand-book, or, Full introduction to the common dialect of that language. (3rd ed.). Madras, Higginbotham & Co.

- ↑ Rajam, V. S. (1992), A Reference Grammar of Classical Tamil Poetry: 150 B.C.-Pre-Fifth/Sixth Century A.D, American Philosophical Society, ISBN 978-0-87169-199-6, retrieved 1 June 2007

- ↑ Schiffman, Harold F. (1995), "Phonetics of Spoken Tamil", A Grammar of Spoken Tamil: 12–13, retrieved 28 August 2009

- ↑ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003), The Dravidian Languages, Cambridge Language Surveys, Cambridge University Press, p. 154, ISBN 0-521-77111-0

- ↑ Kuiper, F. B. J. (1958). "Two problems of old Tamil phonology I. The old Tamil āytam (with an appendix by K. Zvelebil)". Indo-Iranian Journal 2 (3): 191. doi:10.1007/BF00162818.

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamil (1973), The Smile of Murugan, BRILL, p. 4, ISBN 978-90-04-03591-1

- ↑ Ramanujam, A. K.; Dharwadker, V. (eds.) (2000) The collected essays of A.K. Ramanujam, Oxford University Press, p. 111. ISBN 0195639375

- ↑ "Five fold grammar of Tamil", University of Pennsylvania

- ↑ Caldwell, Robert (1875), Classes of nouns in Tamil, Trübner, retrieved 1 June 2007

- ↑ Zvelebil, K. V. (April–June 1972). "Dravidian Case-Suffixes: Attempt at a Reconstruction". Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 92 (2): 272–276. doi:10.2307/600654. JSTOR 600654.

The entire problem of the concept of 'case' in Dravidian will be ignored in this paper. In fact, we might posit a great number of 'cases' for perhaps any Dravidian language once we departed from the familiar types of paradigms forced upon us by traditional, indigenous and European grammars, especially of the literary languages. It is, for instance, sheer convention based on Tamil grammatical tradition (influenced no doubt by Sanskrit) that, as a rule, the number of cases in Tamil is given as eight.

- ↑ Steever, Sanford B. (2002), "Direct and indirect discourse in Tamil", in Güldemann, Tom; von Roncador, Manfred, Reported Discourse: A Meeting Ground for Different Linguistic Domains, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 105, ISBN 90-272-2958-9

- ↑ Lehmann, Thomas (1989), A Grammar of Modern Tamil, Pondicherry: Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture, pp. 9–11

- ↑ Swiderski, Richard M. (1996), The metamorphosis of English: versions of other languages, New York: Bergin & Garvey, p. 61, ISBN 0-89789-468-5

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 Annamalai & Steever 1998, p. 109

- ↑ Tamil is a head-final language, retrieved 1 June 2007

- ↑ WALS – Tamil, Wals.info, retrieved 13 September 2012

- ↑ Ramaswamy, S. (2009). "En/gendering Language: The Poetics of Tamil Identity". Comparative Studies in Society and History 35 (4): 683. doi:10.1017/S0010417500018673.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, p. 480.

- ↑ Meenakshisundaran 1965, pp. 169–193

- ↑ "Literature in all Dravidian languages owes a great deal to Sanskrit, the magic wand whose touch raised each of the languages from a level of patois to that of a literary idiom" (Sastri 1955, p. 309); Trautmann, Thomas R. (2006). Languages and nations: the Dravidian proof in colonial Madras. Berkeley: University of California Press. "The author endeavours to demonstrate that the entire Sangam poetic corpus follows the "Kavya" form of Sanskrit poetry" – Tieken 2001, p. 18.

- ↑ Vaidyanathan, S. (1967). "Indo-Aryan Loan Words in the Cīvakacintāmaṇi". Journal of the American Oriental Society 87 (4): 430. doi:10.2307/597587. JSTOR 597587.

- ↑ Caldwell 1974, pp. 87–88

- ↑ Takahashi, Takanobu. (1995). Tamil love poetry and poetics. Brill's Indological Library, v. 9. Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp. 16, 18. ISBN 9004100423.

- ↑ Pollock, Sheldon (1996). "The Sanskrit Cosmopolis 300–1300: Transculturation, vernacularisation and the question of ideology" in Jan E. M. Houben (ed.), The ideology and status of Sanskrit: Contributions to the history of the Sanskrit language. E. J. Brill, Leiden. pp. 209–217. ISBN 9004106138.

- ↑ Trautmann, Thomas R. (1999), "Hullabaloo About Telugu", South Asian Research 19 (1): 53–70, doi:10.1177/026272809901900104 at p. 64

- ↑ Caldwell 1974, p. 50

- ↑ Ellis, F. W. (1820), "Note to the introduction" in Campbell, A.D., A grammar of the Teloogoo language. Madras: College Press, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ See Ramaswamy's analysis of one such text, the Tamiḻ viṭututu, in Ramaswamy, S. (1998). "Language of the People in the World of Gods: Ideologies of Tamil before the Nation". The Journal of Asian Studies 57: 66. doi:10.2307/2659024. JSTOR 2659024.

- ↑ Varadarajan, M. A History of Tamil Literature, transl. from Tamil by E. Sa. Viswanathan, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, 1988. p. 12: "Since then the movement has been popularly known as the tanittamil iyakkam or the Pure Tamil movement among the Tamil scholars."

- ↑ Ramaswamy, Sumathy (1997), "Laboring for language", Passions of the Tongue: Language Devotion in Tamil India, 1891–1970, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-585-10600-2,

Nevertheless, even impressionistically speaking, the marked decline in the use of foreign words, especially of Sanskritic origin, in Tamil literary, scholarly, and even bureaucratic circles over the past half century is quite striking.

- ↑ Meenakshisundaram, T. P. (1982) A History of Tamil Language, Sarvodaya Ilakkiya Pannai. (translated) pp. 241–2

- ↑ Wall, Frank (1921) Ophidia taprobanica; or, The snakes of Ceylon. H.R. Cottle, govt. printer in Colombo.

- ↑ 148.0 148.1 148.2 "Oxford English Dictionary Online", Oxford English Dictionary, retrieved 14 April 2007

- ↑ "curry, n.2", The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 14 August 2009

References

- Andronov, M.S. (1970), Dravidian Languages, Nauka Publishing House

- Annamalai, E.; Steever, S.B. (1998), "Modern Tamil", in Steever, Sanford, The Dravidian Languages, London: Routledge, pp. 100–128, ISBN 0-415-10023-2

- Caldwell, Robert (1974), A comparative grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages, New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corp.

- Hart, George L. (1975), The poems of ancient Tamil : their milieu and their Sanskrit counterparts, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-02672-1

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003), The Dravidian Languages, Cambridge Language Surveys, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-77111-0

- Kesavapany, K.; Mani, A; Ramasamy, Palanisamy (2008), Rising India and Indian Communities in East Asia, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 981-230-799-0

- Lehmann, Thomas (1998), "Old Tamil", in Steever, Sanford, The Dravidian Languages, London: Routledge, pp. 75–99, ISBN 0-415-10023-2

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003), Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D, Harvard Oriental Series vol. 62, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-01227-5

- Meenakshisundaran, T.P. (1965), A History of Tamil Language, Poona: Deccan College

- Murthy, Srinivasa; Rao, Surendra; Veluthat, Kesavan; Bari, S.A. (1990), Essays on Indian History and culture: Felicitation volume in Honour of Professor B. Sheik Ali, New Delhi: Mittal, ISBN 81-7099-211-7

- Ramstedt, Martin (2004), Hinduism in modern Indonesia, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-7007-1533-9

- Rajam, VS (1992), A Reference Grammar of Classical Tamil Poetry, Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, ISBN 0-87169-199-X

- Ramaswamy, Sumathy (1997), "Laboring for language", Passions of the Tongue: Language Devotion in Tamil India, 1891–1970, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-585-10600-2

- Shapiro, Michael C.; Schiffman, Harold F. (1983), Language and society in South Asia, Dordrecht: Foris, ISBN 90-70176-55-6

- Schiffman, Harold F. (1999), A Reference Grammar of Spoken Tamil, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-64074-1

- Southworth, Franklin C. (1998), "On the Origin of the word tamiz", International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 27 (1): 129–132

- Southworth, Franklin C. (2005), Linguistic archaeology of South Asia, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-33323-7

- Steever, Sanford (1998), "Introduction", in Steever, Sanford, The Dravidian Languages, London: Routledge, pp. 1–39, ISBN 0-415-10023-2

- Steever, Sanford (2005), The Tamil auxiliary verb system, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-34672-X

- Tharu, Susie; Lalita, K., eds. (1991), Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the present – Vol. 1: 600 B.C. to the early twentieth century, Feminist Press, ISBN 1-55861-027-8

- Talbot, Cynthia (2001), Precolonial India in practice: Society, Region and Identity in Medieval Andhra, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513661-6

- Tieken, Herman (2001), Kavya in South India: Old Tamil Cankam Poetry, Gonda Indological Studies, Volume X, Groningen: Egbert Forsten Publishing, ISBN 90-6980-134-5

- Varadarajan, Mu. (1988), A History of Tamil Literature, New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi (Translated from Tamil by E.Sa. Viswanathan)

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1992), Companion studies to the history of Tamil literature, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-09365-6

Further reading

- Fabricius, Johann Philip (1933 and 1972), Tamil and English Dictionary. based on J.P. Fabricius Malabar-English Dictionary, 3rd and 4th Edition Revised and Enlarged by David Bexell. Evangelical Lutheran Mission Publishing House, Tranquebar; called Tranquebar Dictionary.

- Freeman, Rich (February 1998), "Rubies and Coral: The Lapidary Crafting of Language in Kerala", The Journal of Asian Studies (Association for Asian Studies) 57 (1): 38–65, doi:10.2307/2659023, JSTOR 2659023

External links

| Tamil edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| For a list of words relating to Tamil language, see the Tamil language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Tamil at Wikibooks

Tamil at Wikibooks Tamil travel guide from Wikivoyage

Tamil travel guide from Wikivoyage-

Media related to Tamil language at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tamil language at Wikimedia Commons

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||