Symbolics

Symbolics refers to two companies: now-defunct computer manufacturer Symbolics, Inc., and a privately held company that acquired the assets of the former company and continues to sell and maintain the Open Genera Lisp system and the Macsyma computer algebra system.[1]

The symbolics.com domain was originally registered on March 15, 1985, making it the first .com-domain in the world. In August 2009, it was sold to XF.com Investments.[2]

History

Symbolics, Inc.[3] was a computer manufacturer headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and later in Concord, Massachusetts, with manufacturing facilities in Chatsworth, California (a suburban section of Los Angeles). Its first CEO, chairman, and founder was Russell Noftsker.[4] Symbolics designed and manufactured a line of Lisp machines, single-user computers optimized to run the Lisp programming language. Symbolics also made significant advances in software technology, and offered one of the premier software development environments of the 1980s and 1990s, now sold commercially as Open Genera for Tru64 UNIX on the HP Alpha. The Lisp Machine was the first commercially available "workstation" (although that word had not yet been coined).

Symbolics was a spinoff from the MIT AI Lab, one of two companies to be founded by AI Lab staffers and associated hackers for the purpose of manufacturing Lisp machines. The other was Lisp Machines, Inc., although Symbolics attracted most of the hackers, and more funding.

Symbolics' initial product, the LM-2 (introduced in 1981), was a repackaged version of the MIT CADR Lisp machine design. The operating system and software development environment, over 500,000 lines, was written in Lisp from the microcode up, based on MIT's Lisp Machine Lisp.

The software bundle was later renamed ZetaLisp, to distinguish the Symbolics' product from other vendors who had also licensed the MIT software. Symbolics' Zmacs text editor, a variant of Emacs, was implemented in a text-processing package named "ZWEI", an acronym for "Zwei was Eine initially", with "Eine" being an acronym for "Eine Is Not Emacs". Both are recursive acronyms and puns on the German words for "One" ("Eins", "Eine") and "Two" ("Zwei").

The Lisp Machine system software was then copyrighted by MIT, and was licensed to Symbolics. Until 1981, they shared all the source code with MIT and kept it on an MIT server. According to Richard Stallman, Symbolics engaged in a business tactic in which it forced MIT to make all fixes and improvements to the Lisp Machine OS available only to Symbolics, and thereby choke off its competitor LMI, which at that time had insufficient resources to independently maintain or develop the OS and environment.[5]

Symbolics felt that they no longer had sufficient control over their product. At that point, Symbolics began using their own copy of the software, located on their company servers — while Stallman says that Symbolics did that to prevent its Lisp improvements from flowing to Lisp Machines, Inc. From that base, Symbolics made extensive improvements to every part of the software, and continued to deliver almost all the source code to their customers (including MIT). However, the policy prohibited MIT staff from distributing the Symbolics version of the software to others. With the end of open collaboration came the end of the MIT hacker community. As a reaction to this, Stallman initiated the GNU project to make a new community. Eventually, Copyleft and the GNU General Public License would ensure that a hacker's software could remain free software. In this way Symbolics played a key, albeit adversarial, role in instigating the free software movement.

| Model | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LM-2 | 1981 | Workstation based on the MIT CADR architecture |

The 3600 series

In 1983, a year later than planned, Symbolics introduced the 3600 family of Lisp machines. Code-named the "L-machine" internally, the 3600 family was an innovative new design, inspired by the CADR architecture but sharing few of its implementation details. The main processor had a 36 bit word (divided up as 4 or 8 bits of tags, and 32 bits of data or 28 bits of memory address). Memory words were 44 bits, the additional 8 bits being used for error-correcting code (ECC). The instruction set was that of a stack machine. The 3600 architecture provided 4,096 hardware registers, of which half were used as a cache for the top of the control stack; the rest were used by the microcode and time-critical routines of the operating system and Lisp run-time environment. Hardware support was provided for virtual memory, which was common for machines in its class, and for garbage collection, which was unique.

The original 3600 processor was a microprogrammed design like the CADR, and was built on several large circuit boards from standard TTL integrated circuits, both features being common for commercial computers in its class at the time. CPU clock speed varied depending on the particular instruction being executed, but was typically around 5 MHz. Many Lisp primitives could be executed in a single clock cycle. Disk I/O was handled by multitasking at the microcode level. A 68000 processor (known as the "Front-End Processor", or FEP) started the main computer up, and handled the slower peripherals during normal operation. An Ethernet interface was standard equipment, replacing the Chaosnet interface of the LM-2.

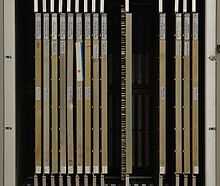

The 3600 was roughly the size of a household refrigerator. This was partly due to the size of the processor — the cards were widely spaced to allow wire-wrap prototype cards to fit without interference — and partly due to the limitations of the disk drive technology in the early 1980s. At the 3600's introduction, the smallest disk that could support the ZetaLisp software was 14 inches (356 mm) across (most 3600s shipped with the 10½-inch Fujitsu Eagle). The 3670 and 3675 were slightly shorter in height, but were essentially the same machine packed a little tighter. The advent of 8 inches (200 mm), and later 5 1⁄4 inches (130 mm), disk drives that could hold hundreds of megabytes led to the introduction of the 3640 and 3645, which were roughly the size of a two-drawer file cabinet.

Later versions of the 3600 architecture were implemented on custom integrated circuits, reducing the 5 cards of the original processor design to 2, at a large manufacturing cost savings but with performance slightly better than the old design. The 3650, first of the "G machines" (as they were known within the company), was housed in a cabinet derived from the 3640s. Denser memory and smaller disk drives enabled the introduction of the 3620, about the size of a modern full-size tower PC. The 3630 was a "fat 3620" with room for more memory and video interface cards. The 3610 was a lower priced variant of the 3620, essentially identical in every way except that it was licensed for application deployment rather than general development.

| Model | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3600 | 1983 | Workstation |

| 3670 | 1984 | Workstation |

| 3640 | 1984 | Workstation |

| 3675 | 1985 | Workstation |

| 3645 | 1985 | Workstation |

The various models of the 3600 family were popular for AI research and commercial applications throughout the 1980s. The AI commercialization boom of the 1980s led directly to Symbolics' success during the decade. Symbolics computers were widely believed to be the best platform available for developing AI software. The LM-2 used a Symbolics-branded version of the complex space-cadet keyboard, while later models used a simplified version (at right), known simply as the Symbolics keyboard.[6] The Symbolics keyboard featured the many modifier keys used in Emacs, notably Control/Meta/Super/Hyper in a block, but did not feature the complex symbol set of the space-cadet keyboard.

Also contributing to the 3600 series' success was a line of bit-mapped graphics color video interfaces, combined with extremely powerful animation software. Symbolics' Graphics Division, headquartered in Westwood, California, a stone's throw from the major Hollywood movie and TV studios, made its S-Render and S-Paint software into industry leaders in the animation business.

Symbolics developed the first workstations capable of processing HDTV quality video, which enjoyed a popular following in Japan. A 3600 — with the standard black-and-white monitor — made a cameo appearance in the movie Real Genius. The company was also referenced in Michael Crichton's novel Jurassic Park.

Symbolics' Graphics Division was sold to Nichimen Trading Company in the early 90s, and the S-Graphics software suite (S-Paint, S-Geometry, S-Dynamics, S-Render) ported to Franz Allegro Common Lisp on SGI and PC computers running Windows NT. Today it is sold as Mirai by Izware LLC, and continues to be used in major motion pictures (most famously in New Line Cinema's The Lord of the Rings), video games, and military simulations.

Symbolic's 3600 series computers were also used as the first front end "controller" computers for the Connection Machine massively parallel computers manufactured by Thinking Machines Inc., another MIT spinoff based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Connection Machine ran a parallel variant of Lisp and, initially, was used primarily by the AI community, so the Symbolics Lisp machine was a particularly good fit as a front-end machine.

For a long time, the operating system didn't have a name, but was finally named "Genera" around 1984. The system included a number of advanced dialects of Lisp. Its heritage was MACLISP on the PDP-10, but it included more data types, and multiple-inheritance object-oriented programming features.

Initially called Lisp Machine Lisp, then ZetaLisp, it finally acquired the name "Symbolics Common Lisp" during the creation of Common Lisp in 1987. Common Lisp is a subset of the dialect available on the Lisp Machine.

Ivory and Open Genera

In the late 1980s (2 years later than planned), the Ivory family of single-chip Lisp Machine processors superseded the G-Machine 3650, 3620, and 3630 systems. The Ivory 390k transistor VLSI implementation designed in Symbolics Common Lisp using NS, a custom Symbolics Hardware Design Language (HDL), addressed a 40-bit word (8 bits tag, 32 bits data/address). Since it only addressed full words and not bytes or half-words, this allowed addressing of 4 Gigawords (GW) or 16 gigabytes (GB) of memory; the increase in address space reflected the growth of programs and data as semiconductor memory and disk space became cheaper. The Ivory processor had 8 bits of ECC attached to each word, so each word fetched from external memory to the chip was actually 48 bits wide. Each Ivory instruction was 18 bits wide and two instructions plus a 2-bit CDR code and 2-bit Data Type were in each instruction word fetched from memory. Fetching two instruction words at a time from memory enhanced the Ivory's performance. Unlike the 3600's microprogrammed architecture, the Ivory instruction set was still microcoded, but was stored in a 1200 x 180-bit ROM inside the Ivory chip. The initial Ivory processors were fabricated by VLSI Technology Inc in San Jose, California, on a 2 µm CMOS process, with later generations fabricated by Hewlett Packard in Corvallis, Oregon, on 1.25 µm and 1 µm CMOS processes. The Ivory had a stack architecture and operated a 4-stage pipeline: Fetch, Decode, Execute and Write Back. Ivory processors were marketed in stand-alone Lisp Machines (the XL400, XL1200, and XL1201), headless Lisp Machines (NXP1000), and on add-in cards for Sun Microsystems (UX400, UX1200) and Apple Macintosh (MacIvory I, II, III) computers. The Lisp Machines with Ivory processors operated at speeds that were between two and six times faster than a 3600 depending on the model and the revision of the Ivory chip.

| Model | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|

| MacIvory I | 1988 | Nubus Board for Apple Macintosh |

| XL400 | 1988 | Workstation, VMEBus |

| MacIvory II | 1989 | Nubus Board for Apple Macintosh |

| UX400 | 1989 | VMEBus Board for SUN |

| XL1200 | 1990 | Workstation, VMEBus |

| UX1200 | 1990 | VMEBus Board for SUN |

| MacIvory III | 1991 | Nubus Board for Apple Macintosh |

| XL1201 | 1992 | Compact Workstation, VMEBus |

| NXP1000 | 1992 | Headless Machine |

The Ivory instruction set was later emulated in software for microprocessors implementing the 64-bit Alpha architecture. The "Virtual Lisp Machine" emulator, combined with the operating system and software development environment from the XL machines, is sold as Open Genera.

Sunstone

Sunstone was a RISC-like processor that was to be released shortly after the Ivory. It was designed by Ron Lebel's group at the Symbolics Westwood office. However, the project was canceled the day it was supposed to tape out.

Endgame

As quickly as the commercial AI boom of the mid-1980s had propelled Symbolics to success, the "AI Winter" of the late 1980s and early 1990s, combined with the slow down of Reagan's "Star Wars" missile defense program, for which DARPA had invested heavily in AI solutions, severely damaged Symbolics. An internal war between Noftsker and the CEO the board had hired in 1986, Brian Sear, over whether to follow Sun's suggested lead and focus on selling their software, or to re-emphasize their superior hardware, and the ensuing lack of focus when both Noftsker and Sear were fired from the company caused sales to plummet. This fact, combined with some ill-advised real estate deals by company management during the boom years (they had entered into large long-term lease obligations in California), drove Symbolics into bankruptcy. Rapid evolution in mass-market microprocessor technology (the "PC revolution"), advances in Lisp compiler technology, and the economics of manufacturing custom microprocessors severely diminished the commercial advantages of purpose-built Lisp machines. By 1995, the Lisp machine era had ended, and with it Symbolics' hopes for success.

Symbolics continued as an enterprise with very limited revenues, supported mainly by service contracts on the remaining MacIvory, UX-1200, UX-1201, and other machines still used by commercial customers. Symbolics also sold Virtual Lisp Machine (VLM) software for DEC, Compaq, and HP Alpha-based workstations (AlphaStation) and servers (AlphaServer), refurbished MacIvory IIs, and Symbolics keyboards.

In July 2005, Symbolics closed its Chatsworth, California, maintenance facility. The reclusive owner of the company, Andrew Topping, died that same year. The current legal status of Symbolics software is uncertain.[7] An assortment of Symbolics hardware was still available for purchase as of August 2007.[8] The US DoD is still paying Symbolics for regular maintenance work.[9]

First .com domain

On March 15, 1985, symbolics.com became the first (and currently, since it is still registered, the oldest) registered .com domain of the Internet.[10] The symbolics.com domain was purchased by XF.com in 2009.

Networking

Genera also featured the most extensive networking interoperability software seen to that point. A local area network system called Chaosnet had been invented for the Lisp Machine (predating the commercial availability of Ethernet). The Symbolics system supported Chaosnet, but also had one of the first TCP/IP implementations. It also supported DECnet and IBM's SNA network protocols. A Dialnet protocol used phone lines and modems. Genera would, using hints from its distributed "namespace" database (somewhat similar to DNS, but more comprehensive, like parts of Xerox's Grapevine), automatically select the best protocol combination to use when connecting to network service. An application program (or a user command) would only specify the name of the host and the desired service. For example, a host name and a request for "Terminal Connection" might yield a connection over TCP/IP using the Telnet protocol (although there were many other possibilities). Likewise, requesting a file operation (such as a Copy File command) might pick NFS, FTP, NFILE (the Symbolics network file access protocol), or one of several others, and it might execute the request over TCP/IP, Chaosnet, or whatever other network was most suitable.

Application Programs

The most popular application program for the Symbolics Lisp Machine was the ICAD computer-aided engineering system. One of the first networked multi-player video games, a version of Spacewar, was developed for the Symbolics Lisp Machine in 1983. Electronic CAD software on the Symbolics Lisp Machine was used to develop the first implementation of the Hewlett-Packard Precision Architecture.

Contributions to computer science

Symbolics' research and development staff (first at MIT, and then later at the company) produced a number of major innovations in software technology:

- Flavors, one of the earliest object-oriented extensions to Lisp, was a message-passing object system patterned after Smalltalk, but with multiple inheritance and a number of other enhancements. The Symbolics operating system made heavy use of Flavors objects. The experience gained with Flavors led to the design of New Flavors, a short-lived successor based on generic functions rather than message passing. Many of the concepts in New Flavors formed the basis of the CLOS (Common Lisp Object System) standard.

- Advances in garbage collection techniques by Henry Baker, David Moon and others, particularly the first commercial use of generational scavenging, allowed Symbolics computers to run large Lisp programs for months at a time.

- Symbolics staffers Dan Weinreb, David Moon, Neal Feinberg, Kent Pitman, Scott McKay, Sonya Keene and others made significant contributions to the emerging Common Lisp language standard from the mid-1980s through the release of the ANSI Common Lisp standard in 1994.

- Symbolics introduced one of the first commercial object-oriented databases, Statice, in 1989. The developers of Statice later went on to found Object Design, Inc. and create ObjectStore.

- Symbolics introduced in 1987 one of the first commercial microprocessors designed to support the execution of Lisp programs: the Symbolics Ivory.[11] Symbolics also used its own CAD system (NS, New Schematic) for the development of the Ivory chip.

- Under contract from AT&T, Symbolics developed Minima, a real-time Lisp run-time environment and operating system for the Ivory processor. This was delivered in a small hardware configuration featuring lots of RAM (no disk) and dual network ports. It was used as the basis for a next-generation carrier class long-distance telephone switch.

- The Graphics Division's Craig Reynolds devised an algorithm that simulated the flocking behavior of birds in flight. "Boids" made their first appearance at SIGGRAPH in the 1987 animated short "Stanley and Stella in: Breaking the Ice", produced by the Graphics Division. Reynolds went on to win the Scientific And Engineering Award from The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1998.

- The Symbolics Document Examiner hypertext system originally used for the Symbolics manuals- it was based on Zmacs following a design by Janet Walker, and proved influential in the evolution of hypertext.

- Symbolics was very active in the design and development of the Common Lisp Interface Manager (CLIM) presentation-based User Interface Management System. CLIM is a descendant of Dynamic Windows, Symbolics' own window system. CLIM was the result of the collaboration of several Lisp companies.

- Symbolics produced the first workstation which could genlock, the first to have real time video I/O, the first to support digital video I/O and the first to do HDTV.[12]

Symbolics Graphics Division

The Symbolics Graphics Division (SGD, founded in 1982, sold to Nichimen Graphics in 1992) developed the S-Graphics software suite (S-Paint, S-Geometry, S-Dynamics, S-Render) for Symbolics Genera.

Movies

This software was also used to create a few computer animated movies and was used for some popular movies.

- 1984, graphics for the little screens about the bridges of the Enterprise and the Klingon ship in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock

- 1985, 3D animations for Real Genius

- 1987, Symbolics, Stanley and Stella in: Breaking the Ice

- 1989, Symbolics, The Little Death

- 1990, Symbolics, Ductile Flow, presented at SIGGRAPH 1990

- 1990, 3D animations for Jetsons: The Movie

- 1991, Symbolics, Virtually Yours

- 1993, 3D animation of the Orca for Free Willy

References

- ↑ Symbolics, Sales by David Schmidt

- ↑ http://www.techcrunch.com/2009/08/27/25-years-later-first-registered-domain-name-changes-hands/

- ↑ Incorporated April 9, 1980, in Delaware by Robert P. Adams, President; Russell Noftsker, Secretary, and Andrew Egendorf, attorney.

- ↑ Noftsker took over as President one year after incorporation.

- ↑ https://www.gnu.org/gnu/rms-lisp.html

- ↑ Xah Lee (2011-10-27). "Space-cadet Keyboard and Lisp Machine Keyboards".

- ↑ http://www.unlambda.com/cadr/cadr_faq.html

- ↑ http://www.lispmachine.net/symbolics.txt

- ↑ "Prime Award Spending Data. Recipient: Symbolics". US Government. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ↑ http://www.jottings.com/100-oldest-dot-com-domains.htm

- ↑ Clark Baker, David Chan, Jim Cherry, Alan Corry, Greg Efland, Bruce Edwards, Mark Matson, Henry Minsky, Eric Nestler, Kalman Reti, David Sarrazin, Charles Sommer, David Tan and Neil Weste (1987). "The Symbolics Ivory Processor: A 40 Bit Tagged Architecture Lisp Microprocessor". Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Design. pp. 512–4.

- ↑ The Computer Graphics Essential Reference

Further reading

- David A. Moon. "Garbage collection in a large LISP system". Proceedings of the 1984 ACM Symposium on LISP and functional programming, August 6–8, 1984, Austin, Texas. pp. 235–246.

- David A. Moon. "Architecture of the Symbolics 3600". Proceedings of the 12th annual international symposium on Computer architecture, June 17–19, 1985, Boston, Massachusetts. pp. 76–83.

- Moon, D. A. (1986). "Object-oriented programming with flavors". In N. Meyrowitz. Conference Proceedings on Object-Oriented Programming Systems, Languages and Applications (Portland, Oregon, United States, September 29–October 2, 1986). OOPLSA '86. New York, NY: ACM. pp. 1–8.

- D. A. Moon (January 1987). "Symbolics Architecture". Computer 20 (1): 43. doi:10.1109/MC.1987.1663356.

- J. H. Walker, D. A. Moon, D. L. Weinreb, M. McMahon (November 1987). "The Symbolics Genera Programming Environment". IEEE Software 4 (6): 36–45. doi:10.1109/MS.1987.232087.

- Bruce Edwards, Greg Efland, Neil Weste. "The Symbolics I-Machine Architecture". IEEE International Conference on Computer Design '87.

- Walker, J. H. (1987). "Document Examiner: delivery interface for hypertext documents". Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Hypertext (Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States). HYPERTEXT '87. New York, NY: ACM. pp. 307–323.

- G. Efland et al. (January 1988). The Symbolic Ivory Processor: A VLSI CPU for the Genera Symbolic Processing Environment. Symbolics Cambridge Center, VLSI System Group.

- Shrobe, H. E. (1988). "Symbolic computing architectures". Exploring Artificial intelligence. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann. pp. 545–617.

- Walker, J. H. (1988). "Supporting document development with concordia". In B.D. Shriver. Proceedings of the Twenty-First Annual Hawaii international Conference on Software Track (Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, United States). Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society. pp. 355–364. doi:10.1109/HICSS.1988.11825.

- McKay, S., York, W., McMahon, M. (1989). "A presentation manager based on application semantics". Proceedings of the 2nd Annual ACM SIGGRAPH Symposium on User interface Software and Technology (Williamsburg, Virginia, United States, November 13–15, 1989). UIST '89. New York, NY: ACM. pp. 141–8.

- McKay, S. (September 1991). "CLIM: the Common Lisp interface manager". Comm. ACM 34 (9): 58–9. doi:10.1145/114669.114675.

External links

- The current symbolics.com website

- The Symbolics Museum

- Archives from the Symbolics Lisp Users Group (SLUG) Mailing List, 1986-1993

- Archives from the Symbolics Lisp Users Group (SLUG) Mailing List, 1990-1999

- Ralf Möller's Symbolics Lisp Machine Museum

- "Genera Concepts" — (Web copy of Symbolic's introduction to Genera)

- A collection of press releases from Symbolics

- "Symbolics announces the first true Single-Chip Lisp CPU" — (Symbolics press release announcing the Ivory chip)

- Lisp machines timeline -(a timeline of Symbolics' and others' Lisp machines)

- "Why Did Symbolics Fail?" -(by Daniel Weinreb)

- Kalman Reti, the Last Symbolics Developer, Speaks of Lisp Machines. — Video of a talk from June 28, 2012