Supyire language

| Supyire | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Mali, Ivory Coast |

| Region | Sikasso Region |

Native speakers | 460,000 (1996–2007)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

Either: spp – Supyire seb – Shempire (Syenpire, duplicate code) |

| Glottolog |

supy1237[2] |

|

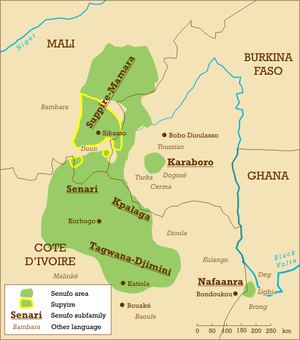

Map showing where Supyire is spoken. | |

Supyire, or Suppire, is a Senufo language spoken in the Sikasso Region region of southeastern Mali and in adjoining regions of Ivory Coast, where it is known as Shempire (Syenpire). In their native language, the noun sùpyìré means both "the people" and "the language spoken by the people".

Background

The early existence of Supyire is unclear. During the time period in which the language developed, it has been hypothesized that there was little conflict in the region which resulted in a significant amount of separation between the ancestors of the Supyire and other cultures of the area. If individuals speaking a single language migrated to the region of present-day Mali and then broke off into small groups that had little connection, it would be expected that the languages would develop different characteristics over time. Recently, close contact with other tribes has resulted in a dictionary full of loan words that have been assimilated into everyday language. Education has had an impact on any cultural language in this area. Although few are literate, many children attend primary school where a mixture of languages can be presented. There is ongoing controversy over the use of “mother tongues” in schools. Current law states that primary schools educate in the mother tongue whereas secondary schools emphasize the use of a common language.

The language group of Senufo can be divided into northern, central, and southern branches, with Supyire being classified as the southernmost northern Senufo language. The Senufo language group, with approximately 2. 2 million speakers, extends from the southwest corner of Mali and covers a significant portion of the northern Ivory Coast. There are also isolated pockets of this language group in Burkina Faso and Ghana. As a group, the Senufo people are considered to be one of the oldest ethnic groups of the Ivory Coast, having settled there in the early 17th century. It is hypothesized that the Senufo descended from the Kenedugu people, who ruled over Mali and Burkina Faso during the 17th century. It was this culture that established the village of Sikasso, which now stands as the cultural center for the Supyire people. Sikasso was the last city to fall into French control during their invasion of Mali in 1888. Mali existed under French Colonial rule as the nation of French Sudan. In 1958, French Sudan claimed autonomy and was renamed the Sudanese Republic. In 1960 the Sudanese Republic became the independent country of Mali.

As a group of people, the Supyire survive by cultivating the landscape. Individuals make a living off of the land, primarily by cultivating yams, millet, and sorghum, a tradition that has perpetuated through their ancestral history. With the integration of agricultural processes from neighboring cultures, bananas and manioc have also been successfully cultivated. Care of livestock, including chickens, sheep, goats, and guinea fowl, provides a significant source of nutrition. In this culture, wealth is correlated to the number and quality of livestock as opposed to money. Both hunting and fishing are also important, although to a much smaller degree. Although the Supyire have risen above the level of hunter-gatherer, their traditional mode of organization has not risen above the village level. In Supyire culture it is rare that any single person holds excessive power and there are only two traditional classes- the laborers and the farmers.

As a culture, the Supyire, and most Senufo groups, are most known for their artwork. Artisans in these communities are regarded to the highest degree. Most artwork consists of sculptures used to bring deities to life. Animal figures such as zebras, crocodiles, and giraffes are very common. Storytelling also plays a significant role in this culture and one of the first written documents of the Supyire was a story entitled “Warthog’s Laughter Teeth”. The Senufo practice of female circumcision has made this culture recognizable on a worldwide level. The practice of female circumcision, done for cultural or religious reasons, is meant to mark a right of passage as girls become women. In these cultures, men are also expected to go through various rights of passage. The predominant religion of the region is Muslim, although most “bushmen” tend to instead place their faith in human-like gods. Worshipping of deceased ancestors is also common.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ɲ | ||

| Plosive / Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | ʔ |

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | g | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | |||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||

Supyire has a voicing distinction and contains a glottal stop, a common characteristic in African languages. However, it does not have labial–velar consonants.

Voiceless stops have particular limitations and are only used in three environments: word initial, such as tàcwɔ̀ (“fiancée”); medially in a stressed syllable, as in nupéé; or following a nasal, such as in kàntugo (“behind”). Moreover, almost every word-initial /ɡ/ is found in loanwords from either French or Bambara.

Although both voiceless and voiced fricatives are found, voiceless fricatives such as /f/ and /s/ are much more common than the voiced fricatives /v/, /z/, and /ʒ/.

There is no labial approximant.

In speech, /w/ does not come after a short stressed syllable.[4]

Although Supyire contains nasal consonants, there is considerable debate over their phonemic status. According to a well-formulated hypothesis, the predecessor of Supyire had no nasal consonants but nasalized vowels did exist. Some linguists thus categorize nasal consonants as simple variants of the approximants that occur before nasal vowels.

Supyire is reported to have the rare uvular flap as an allophone of /ɡ/ in unstressed syllables.[5] This parallels /d/ surfacing as [ɾ] in the same environment.[5]

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ĩ | u ũ | |

| Close-mid | e | o | |

| Open-mid | ɛ ɛ̃ | ɔ ɔ̃ | |

| Open | a ã |

Supyire has 12 vowels in total, with seven oral vowels and five nasal vowels. Two oral vowels, /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ are not as well-established as the other five because the difference between /ɛ/ and /a/ is neutralized and, when speaking quickly, it is very difficult to distinguish between /ɑ/, a variant of /ɔ/, and /a/. It does appear that some speakers preferentially choose one pronunciation over the other, although some do use both pronunciations and some use a variant somewhere in the middle.

Vowel harmony is also important in the Supyire language. This is done by harmonizing unstressed vowels with the initial stressed vowel if they both belong to the same root or have the same suffix.

Syllables

Supyire has a noticeable syllable structure that includes no closed syllables. In Supyire, syllables are most often either CV or CVV although the pronouns u and uru both begin with a vowel syllable. Supyire words also tend to have only one stressed syllable in every root. Stress is most often placed on the initial syllable of a root although many roots exist with no stress on the first syllable. Affixes and other grammatical sounds, such as those that indicate pronouns, do not have stress.

Tone

Supyire is tonal (common in African languages).

The language has four basic tones: high, low, strong mid, and weak mid. While the high and low tones are unremarkable, the two mid tones are only differentiated by differences in their behavior when referencing tone rules, and not by their pitch. These unusual mid tones are found in all northern Senufo languages but not in central Senufo languages, which only have three tones.

Most vowels in the Supyire language contain a single tone although vowels may have two, or in extremely rare cases three, tones. Further, nasals that come before stops can only have one tone. Basic noun gender suffixes, imperfective verb suffixes, the causative verb suffix –g followed by a vowel, and the intransitive verb prefix N- are considered toneless.

It was noted that boys who spent their days herding cows communicated with each other strictly through whistled language, which only elaborated vowel length and pitch. These small pieces of information were enough to have conversations of considerable detail.

Morphology

Class System

The noun class system of Supyire is similar to that of other languages in the Niger–Congo family. This system includes eight noun classes that are grouped into five noun genders. While there is noun class agreement between pronouns and their head nouns, there is no verb agreement. However, there is agreement between quantifiers (such as determiners and independent adjectives) and the head noun.

The gender system of Supyire does differ slightly from the gender systems of other similar languages. Bantu, also a subgroup of Niger–Congo languages, places different forms of the same word into varying gender classes. For example, the Swahili word for friend is rafiki and it is a class 9 noun. However, the plural form marafiki belongs to noun class 6 (Wikipedia). This confusion over noun class distinction does not occur in any Senufo language, Supyire included.

In Supyire, gender 1 is categorized as the “human” gender. It is interesting to note that instead of classifying loan words by their definition, those who speak Supyire tend to classify loan words by their suffixes and thus most loan words, regardless of meaning, are placed into gender 1. More than half of the dictionary of gender one nouns is loan words. Nouns found in this category range from general human terms such as ceewe (“woman”) and pyà (“child”) to terms that describe relationships such as nafentu (“wife’s father”). Also found in this category are terms that describe people such as ̀ŋaŋa (“twin”) or cevoo (“friend”). Gender 1 also contains class terms and occupational terms such as ciiwe (“leather-worker”), tunntun (“blacksmith”) and sòròlashí (“soldier”). Supernatural entities are also categorized into the human gender. The word for god, kile, is categorized as a gender 1 noun. This gender also contains some “higher” animals and mass nouns such as dust and sand.

Gender 2 is typically described as the category that contains nouns that are “big things” while gender 3 contains nouns of “small things”. Thus, gender 2 includes, for example, trees and tree parts such as cige (“tree”), logo (“shea tree”), and weŋe (“leaf”). Also included in gender 2 are large, immovable objects such as baga (“house, building”), caanga (“market”) and kacige (“bridge”) and most large animals. Gender 2 contains nouns that describe desires such as katege (“hunger”) and byaga (“thirst”). Gender 3 contains small animals such as lùpààn (“mosquito”). Gender 4 is known as the “collectives” category and contains mass nouns and abstract nouns. Some examples of mass nouns are pworo (“adobe”) and kyara (“meat”). Abstracts are used to convey emotional states and include words such as sícyere (“insanity”) and wyere (“cold”). The final category of noun gender 5 contains nouns for liquids. For example, this is the gender of sìnmε (“beer”) and jirimε (“milk”).

In Supyire, gender is marked by suffixes. Basic gender suffixes in Supyire most often have the form –CV, seen in six of the eight classes. Suffixes in this instance are toneless. The first three gender systems include both singular and plural forms while gender 4 and 5 do not. For example, singular gender 1 nouns employ the use of the suffix –wV, singular gender 2 nouns use –gV normally, singular gender 3 nouns employ the use of –lV, gender 4 nouns use the basic suffix –rV, and gender 5 uses –mV as a suffix. Plural gender 1 nouns do not adhere so strictly to the rules and can vary in consonant usage. However, all end in –ii or –íí.

Verb Morphology

Although Niger–Congo languages tend to have complicated verb morphology systems, Supyire does not follow this trend. There are only four types of affixes seen in the Supyire language- verb prefixes, imperfective aspect suffixes, the causative suffix, and the plural or intensive suffix. The language of Supyire also uses verb compounding, although the system is very basic. Supyire is both a prefixing and suffixing language. There are two verb prefixes used in Supyire- an intransitive prefix and a future prefix. The perfect and recent past do not have prefixes. The intransitive prefix is marked only by a toneless nasal. It is interesting to note that the intransitive prefix exists only with verbs that begin with voiceless the prefix depends on the location of the direct object in a sentence (see below, examples C and D). This is exemplified by the following:

a. Voiceless stop—prefix appears

Pi màha m-pa náhá. They HAB IP-come here. “They come here.”

b. Fricative—no prefix Pi màha shya aní

c. Mìì ná m̀pà ta. I PAST sheep get “I got a sheep.”

d. Mpà mìì ná ń-tá. sheep I PAST IP-get. “It was a sheep that I got.”

Alternatively, the future prefix is used with verbs that apply a future time reference. In conjunction with certain verb prefixes, the auxiliaries sí and cáá are also used. It also differs from the first prefix in that it uses a distinct tone and it appears on all verbs, not just those beginning with voiceless stops. Just as with the intransitive prefix, the future prefix uses a nasal attached to a verb that is not preceded by a direct object. As an example:

a.Mìì sí m̀-pà. I FUT FP-come. “I will come.”

Adjectives

Supyire does not include many adjectives, since most adjectives can be represented by the use of stative verbs instead. However, a small group of adjectives do exist. Adjectives are created in two ways in Supyire: either by compounding or by using derived adjectives. The following are examples of adjectival roots and root compounding:

a. Root: -fu- ("hot")

b. kafee-fu-go (“hot wind”)

Syntax

Sentence Structure

Although almost all Niger–Congo languages have a sentence structure that follows the subject–verb–object pattern, Supyire and other Senufo languages do not follow in this way. Instead, these languages are verb-final and most often are subject–object–verb. The following examples provide evidence for this sentence structure:

a. Kà u ú ŋ́́-káré sà a ci-ré pààn-nì. “He went to chop the trees”

DS G1S NARR IP-go go PROG tree-DEF.G4 chop-IMPV

b. Lùpà-àn sì ǹ-tὲὲn ù nà. “A mosquito sat on him”

A mosquito-G3S NARR IP-sit G1S on

Number System

The number system of the Supyire people is unique, and quite confusing. Values exist for numbers 1-5, 10, 20, 80, and 400. Strangely, all of these numerals are members of gender 1 except “four hundred”, which is in gender 3. The numbers 6-9 are formed using a combination of basic math and the prefix baa–. The word for “six” is baa-nì, translated to mean “five and one”, although the root of “one” has been shortened. After ten, a distinct prefix is associated with the teens, twenties, thirties, and so on (see Table 4). The word for 80, ŋ`kùù, is formally and etymologically identical to the word for 'chicken'. This identity is inexplicable to speakers; Carlson (1994) supposes it to relate to a historical price of a chicken.

Because of obvious confusion with this number system and close contact with neighboring Bambara people, the Supyire have been slowly disregarding this system. Like other languages in this region, numerals that refer to money (in this instance, the franc) are counted in groups of five.

See also

Sources

- Carlson, R. (1991). Of postpositions and word order in Senufo languages. Approaches to

Grammaticalization, 2, 201-223.

- Carlson, R. (1994). A Grammar of Supyire. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

- Comrie, B., Matthews, S., & Polinsky, M. (2003). Chapter 4: Africa and the Middle East. In The Atlas of Languages (pp. 72–89). London: Piers Spence.

- Garber-Kompaore, A. (1987). A Tonal Analysis of Senufo: Sucite dialect . Dissertation Abstracts, 1.

Retrieved December 1, 2008, from University of Illinois Web site:[7]

- Nurse, D., & Heine, B. (2000). African Languages. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Pike, K. (1964). Tone Languages: A Technique . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Trudell, B. (2007, September). Local community perspectives and language education in sub-Saharan African communities. International Journal of Educational Development, 27(5), 552-563.

References

- ↑ Supyire at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Shempire (Syenpire, duplicate code) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Supyire Senoufo". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Carlson 1994, p. 8.

- ↑ Carlson, 1994, p. 17.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Carlson 1994, p. 10.

- ↑ Carlson, 1994, p. 28.

- ↑ Tonal Analysis of Senufo: Sucite Dialect

External links

- Genitive focus in Supyire PDF (324 KB)

- Interroɡative pronouns in Supyire PDF (121 KB)

- Resources in Supyiré from SIL Mali