Supraspinatus muscle

| Supraspinatus muscle | |

|---|---|

Position of the supraspinatus muscle (red) seen from the back. | |

|

Posterior view of muscles connecting the upper extremity to the vertebral column. Supraspinatus muscle is labeled in red at right, while it is covered by other muscles at left. | |

| Details | |

| Latin | musculus supraspinatus |

| supraspinous fossa of scapula | |

| superior facet of greater tubercle of humerus | |

| suprascapular artery | |

| suprascapular nerve | |

| Actions | abduction of arm and stabilizes humerus see part on controversy of action. |

| Identifiers | |

| Gray's | p.440 |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | m_22/12551039 |

| TA | A04.6.02.006 |

| FMA | 9629 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The supraspinatus (plural supraspinati, from Latin supraspinatus) is a relatively small muscle of the upper back that runs from the supraspinatous fossa superior of the scapula (shoulder blade) to the greater tubercle of the humerus. It is one of the four rotator cuff muscles and also abducts the arm at the shoulder. The spine of the scapula separates the supraspinatus muscle from the infraspinatus muscle, which originates below the spine.

Structure

The supraspinatus muscle arises from the supraspinous fossa, a shallow depression in the body of the scapula above its spine. The supraspinatus muscle tendon passes laterally beneath the cover of the acromion. Research in 1996 showed that the postero-lateral origin was more lateral than classically described.[1][2]

The supraspinatus tendon is inserted into the superior facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus. The distal attachments of the three rotator cuff muscles that insert into the greater tubercle of the humerus can be abbreviated as SIT when viewed from superior to inferior (for supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor), or SITS when the subscapularis muscle, which attaches to the lesser tubercle of the humerus, is included.[3]

Innervation

The supraspinatus muscle is supplied by the suprascapular nerve (C5 and C6), which arises from the superior trunk of the brachial plexus and passes laterally through the posterior triangle of the neck and through the scapular notch on the superior border of the scapula. After supplying fibers to the supraspinatus to the capsule of the shoulder joint.

This nerve can be damaged along its course in fractures of the overlying clavicle, which can reduce the person’s ability to initiate the abduction.

Repair

One study has indicated that arthroscopic surgery for full-thickness supraspinatus tears is effective for improving shoulder functionality.[4]

Function

Contraction of the supraspinatus muscle leads to abduction of the arm at the shoulder joint. It is the main agonist muscle for this movement during the first 10-15 degrees of its arc. Beyond 30 degrees the deltoid muscle becomes increasingly more effective at abducting the arm and becomes the main propagator of this action.

The supraspinatus muscle is one of the musculotendinous support structures called the rotator cuff that surround and enclose the shoulder. It helps to resist the inferior gravitational forces placed across the shoulder joint due to the downward pull from the weight of the upper limb.

The supraspinatus also helps to stabilize the shoulder joint by keeping the head of the humerus firmly pressed medially against the glenoid fossa of the scapula.

Without a functioning supraspinatus, the physician must start abducting the patient's arm and eventually the patient will be able to finish abduction if the deltoid is functional, which is common because the supraspinatus is innervated by the suprascapular nerve from the superior/upper trunk of the brachial plexus. The deltoid is innervated more distally by the axillary nerve, which arises from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus.

Controversy about action

In a 1963 experimental human study on the function of the supraspinatus muscle by Van Linge and Mulder at the State University in Leiden, data were provided arguing that the supraspinatus does not cause the first 30 degrees of abduction, as widely accepted before this report, but is, rather, a synergistic muscle that assists the deltoid (but does not abduct alone).[5] In the study, the supraspinati of subjects were anaesthetised; the deltoid muscle remained able to complete a full range of abduction. (However, the deltoid was unable to sustain an isometric contraction for more than one minute.) This study suggested that the "true" action of the supraspinatus is to hold the capsule in position to allow greater functional strength and stamina of the deltoid muscle.

In support of this study, one should also consider the basic mechanics of the forces involved in abduction of the shoulder. The supraspinatus is a smaller and weaker muscle compared to deltoid on three counts: deltoid has three large components (anterior, middle, and posterior fiber groups); the middle fibers have a multipennate arrangement believed to pack more muscle power into a relatively compact space;[6] and it attaches to the deltoid tuberosity half way down the humerus, adding to the mechanical advantage to abduct the arm. Thus the bulk, arrangement and insertion of the deltoid fibres are designed for the power needed to overcome the load of the weight of the arm plus any load in the hand. By contrast, supraspinatus is a much smaller muscle with convergent fibers leading to a tendon that attaches on the highest facet on the greater tubersosity of the humerus, thereby affording it minimal traction on the arm. The arm is a very long lever with the added weight of muscles and other soft tissues. In 1994, Sharkey and coworkers reported that the whole of the rotator cuff group contributes to abduction of the arm, reducing the work of deltoid by 41%.[7] They strongly suggested that the rotator cuff acts synergistically in concert with deltoid to stabilize the head of the humerus, while the deltoid provides the turning moment at the gleno-humeral joint to abduct the arm. They note that if the deltoid is palpated when abduction is initiated, active contraction of the muscle can be detected—suggesting co-contraction of deltoid with the rotator cuff, rather than after initiation by any of the rotator cuff muscles.

Additional images

-

Position of the supraspinatus muscle (shown in red). Animation.

-

Muscles around the left shoulder, seen from behind.

3. Latissimus dorsi muscle

5. Teres major muscle

6. Teres minor muscle

7. Supraspinatus muscle

8. Infraspinatus muscle

13. long head of Triceps brachii muscle. -

.gif)

Action of right supraspinatus muscle, anterior view. Three bones shown are acromion (top) and coracoid process (center) of scapula, and humerus (left).

-

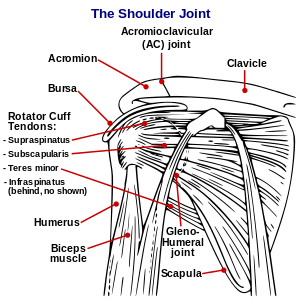

Diagram of the human shoulder joint

-

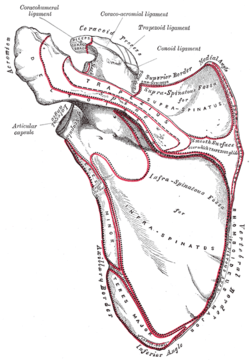

Left scapula. Dorsal surface.

-

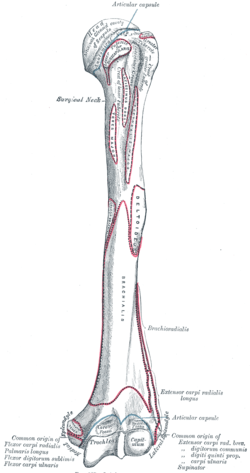

Left humerus. Anterior view.

-

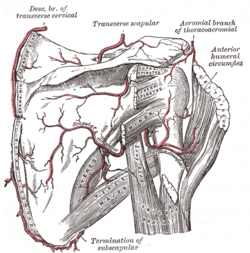

The scapular and circumflex arteries.

-

The right brachial plexus with its short branches, viewed from in front.

-

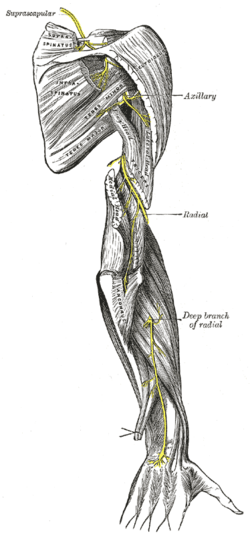

Suprascapular and axillary nerves of right side, seen from behind.

-

The suprascapular, axillary, and radial nerves.

References

- ↑ H. Thomazeau, J.M. Duval, P. Darnault & T. Dréano, 1996, Anatomical relationships and scapular attachments of the supraspinatus muscle, Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 18(3), 221-225, see accessed 21 November 2014.

- ↑ D.F. Gazielly, P. Gleyze & T. Thomas, 1996, "The Cuff," Elsevier, ISBN 2906077844, see , accessed 21 November 2014.

- ↑ MedicalMnemonics.com: 35

- ↑ Bennett, William F. "Arthroscopic Supraspinatus Repair". Bennett Orthopedics & Sportsmedicine. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ B. van Linge and J.D. Mulder, 1963, "Function of the Supraspinatus Muscle and its Relation to the Supraspinatus syndrome: An Experimental Study in Man," J. Bone Joint Surg. 45B(4), 750–754, see , accessed 21 November 2014.

- ↑ Gray's Anatomy 37th Edition 1987

- ↑ N.A. Sharkey1, R.A. Marder & P.B. Hanson, 1994, The entire rotator cuff contributes to elevation of the arm, J. Orthopaedic Res. 12(5), 699–708, DOI: 10.1002/jor.1100120513, see , accessed 21 November 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Supraspinatus muscles. |

- ‹The template EMedicineDictionary is being considered for deletion.› supraspinatus+muscle at eMedicine Dictionary

- GoogleBody - Supraspinatus muscle

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||