Supply-chain operations reference

Supply-chain operations reference-model (SCOR) is a process reference model for supply chain management. This reference model enables users to address, improve, and communicate supply chain management practices within and between all interested parties in the extended enterprise.[1]

The supply-chain operations reference-model is developed in 1996[2][3] by the management consulting firm PRTM, now part of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC) and AMR Research, now part of Gartner, and endorsed by the Supply-Chain Council (SCC), now part of APICS, as the cross-industry de facto standard strategy, performance management, and process improvement diagnostic tool for supply chain management.

The supply-Chain Operations Reference is a management tool, spanning from the supplier's supplier to the customer's customer. The model has been developed by the members of the Council on a volunteer basis to describe the business activities associated with all phases of satisfying a customer's demand.

Supply-chain operations reference-model pillars

The model is based on 3 major "pillars":

- Process modeling and re-engineering

- Performance measurements

- Best practices

The process modeling pillar

By describing supply chains using process modeling building blocks, the model can be used to describe supply chains that are very simple or very complex using a common set of definitions. As a result, disparate industries can be linked to describe the depth and breadth of virtually any supply chain.

SCOR is based on six distinct management processes: Plan, Source, Make, Deliver, Return, and Enable.[4][5]

- Plan – Processes that balance aggregate demand and supply to develop a course of action which best meets sourcing, production, and delivery requirements.

- Source – Processes that procure goods and services to meet planned or actual demand.

- Make – Processes that transform product to a finished state to meet planned or actual demand.

- Deliver – Processes that provide finished goods and services to meet planned or actual demand, typically including order management, transportation management, and distribution management.

- Return – Processes associated with returning or receiving returned products for any reason. These processes extend into post-delivery customer support.

- Enable - New process since Version 11 (Dec 2012).

With all reference models, there is a specific scope that the model addresses. SCOR is no different and the model focuses on the following:

- All customer interactions, from order entry through paid invoice.

- All product (physical material and service) transactions, from your supplier’s supplier to your customer’s customer, including equipment, supplies, spare parts, bulk product, software, etc.

- All market interactions, from the understanding of aggregate demand to the fulfillment of each order.

SCOR does not attempt to describe every business process or activity. Relationships between these processes can be made to the SCOR and some have been noted within the model. Other key assumptions addressed by SCOR include: training, quality, information technology, and administration (not supply chain management). These areas are not explicitly addressed in the model but rather assumed to be a fundamental supporting process throughout the model.

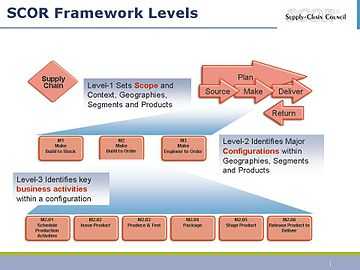

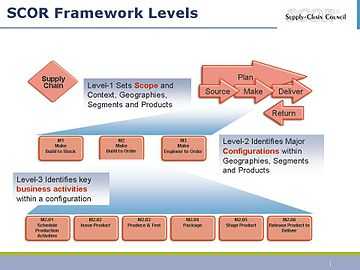

SCOR provides three-levels of process detail.[6] Each level of detail assists a company in defining scope (Level 1), configuration or type of supply chain (Level 2), process element details, including performance attributes (Level 3). Below level 3, companies decompose process elements and start implementing specific supply chain management practices. It is at this stage that companies define practices to achieve a competitive advantage, and adapt to changing business conditions.

SCOR is a process reference model designed for effective communication among supply chain partners. As an industry standard it also facilitates inter and intra supply chain collaboration, horizontal process integration, by explaining the relationships between processes (i.e., Plan-Source, Plan-Make, etc.). It also can be used as a data input to completing an analysis of configuration alternatives (e.g., Level 2) such as: Make-to-Stock or Make-To-Order. SCOR is used to describe, measure, and evaluate supply chains in support of strategic planning and continuous improvement.

In the example provided by the picture the Level 1 relates to the Make process. This means that the focus of the analysis will be concentrated on those processes that relate to the added-value activities that the model categorizes as Make processes.

Level 2 includes 3 sub-processes that are “children” of the Make “parent”. These children have a special tag – a letter (M) and a number (1, 2, or 3). This is the syntax of the SCOR model. The letter represents the initial of the process. The numbers identify the “scenario”, or “configuration”.

M1 equals a “Make build to stock” scenario. Products or services are produced against a forecast. M2 equals a “Make build to order” configuration. Products or services are produced against a real customer order in a just-in-time fashion. M3 stands for “Make engineer to order” configuration. In this case a blueprint of the final product is needed before any make activity can be performed.

Level 3 processes, also referred to as the business activities within a configuration, represent the best practice detailed processes that belong to each of the Level 2 “parents”.

The example shows the breakdown of the Level 2 process “Make build to order” into its Level 3 components identified from M2.01 to M2.06. Once again this is the SCOR syntax: letter-number-dot-serial number.

The model suggests that to perform a “Make build to order” process, there are 6 more detailed tasks that are usually performed. The model is not prescriptive, in the sense that it is not mandatory that all 6 processes are to be executed. It only represents what usually happens in the majority of organizations that compose the membership base of the Supply Chain Council.

The Level 3 processes reach a level of detail that cannot exceed the boundaries determined by the industry- agnostic and industry-standard nature of the SCOR model. Therefore all the set of activities and processes that build – for instance – the M2.03 “Produce & test” process will be company-specific, and therefore fall outside the model’s scope.

The Performance Measurements Pillar

The SCOR model contains more than 150 key indicators that measure the performance of supply chain operations.[7] These performance metrics derive from the experience and contribution of the Council members. As with the process modeling system, SCOR metrics are organized in a hierarchical structure.

- Level 1 metrics are at the most aggregated level, and are typically used by top decision makers to measure the performance of the company's overall supply chain.

- Level 2 Metrics are primary, high level measures that may cross multiple SCOR processes.

- Level 3 Metrics do not necessarily relate to a SCOR Level 1 process (PLAN, SOURCE, MAKE, DELIVER, RETURN).

The metrics are used in conjunction with performance attributes. The Performance Attributes are characteristics of the supply chain that permit it to be analyzed and evaluated against other supply chains with competing strategies. Just as you would describe a physical object like a piece of lumber using standard characteristics (e.g., height, width, depth), a supply chain requires standard characteristics to be described. Without these characteristics it is extremely difficult to compare an organization that chooses to be the low-cost provider against an organization that chooses to compete on reliability and performance.

One of the key aspect that needs to be considered is that the performance measurement and thus bench-marking is done at supply chain level and not at the organizational level. Supply chains are identified with an organization based on customers and products. An organization which is offering multiple products will have multiple supply chains. In fact the supply chain to deliver the material and then returns of the material from customer will also be different.

Then the supply chain which needs to be improved is identified, this could be based on multiple parameters highest profitable, loss making. Once the supply chain is identified then only the performance measurement and bench-marking are done. Please note SCOR might not have the bench-marking data for all kind of supply chain so one needs to check with them i.e. SCOR currently doesn't have data for "catering supply chain" in Airline industry. The point here is that SCOR is for improving supply chains in an organization and the premise is that if a single supply chain is improved it has ripple effect on the complete organization.

Associated with the Performance Attributes are the Level 1 Metrics. These Level 1 Metrics are the calculations by which an implementing organization can measure how successful they are in achieving their desired positioning within the competitive market space.

The metrics in the Model are hierarchical, just as the process elements are hierarchical. Level 1 Metrics are created from lower level calculations. (Level 1 Metrics are primary, high level measures that may cross multiple SCOR processes. Level 1 Metrics do not necessarily relate to a SCOR Level 1 process (PLAN, SOURCE, MAKE, DELIVER, RETURN). Lower level calculations (Level 2 metrics) are generally associated with a narrower subset of processes. For example, Delivery Performance is calculated as the total number of products delivered on time and in full based on a commit date.

The best-practices pillar

Once the performance of the supply chain operations has been measured and performance gaps identified, it becomes important to identify what activities should be performed to close those gaps. Over 430 executable practices derived from the experience of SCC members are available.[8]

The SCOR model defines a best practice as a current, structured, proven and repeatable method for making a positive impact on desired operational results.[9]

- Current – Must not be emerging (bleeding edge) and must not be antiquated

- Structured – Has clearly stated Goal, Scope, Process, and Procedure

- Proven – Success has been demonstrated in a working environment.

- Repeatable – The practice has been proven in multiple environments.

Method- Used in a very broad sense to indicate: business process, practice, organizational strategy, enabling technology, business relationship, business model, as well as information or knowledge management.

- Positive impact on desired operational results

The practice shows operational improvement related to the stated goal and could be linked to Key Metric(s). The impact should show either as gain (increase in speed, revenues, quality) or reduction (resource utilizations, costs, loss, returns, etc.).

An example of how to use SCOR

SCOR improves on this by offering a "standard" solution. The first step is to recover the Level 1 and Level 2 process descriptions.

The example is of a simple supply chain.

The picture alone cannot adequately describe what production strategy the manufacturing company has decided to adopt. It is no easier to figure out how the material is supplied from the two suppliers. For example, is the material delivered against a forecast or is it pulled based on real consumption?

Even in its apparent simplicity this picture does not represent a standard. Without a more extensive description the picture does not help interpret what is actually happening in this supply chain. Descriptive text could be added to the images to help explain the whole process. In order to keep the example simple and direct, it focuses only on the central processes: Source, Make, and Deliver. This reflects the general practice of members who focus first of all on these three process scopes. Only in a second step do they apply Plan and Return to map all their supply chain processes.

The description of the manufacturing company reads “Manufacturing company That Produces against a 15-day forecast”. The key word here is “forecast”. What is the SCOR scenario that resembles a production based on forecast? The answer is, M1 (Make build to stock).

How does the company supply materials from the Far East? The box reads “Supplies raw materials in bulks from the Far East against a monthly forecast”. “Forecast” is again the keyword. How a process of supply based on a forecast be represented? The process is “Source”. The picture from the SCOR manual shows that the process S1 “Source Stocked Product” exactly corresponds to the needs of this example.

With the French supplier, the company “Pulls components from France based on production volumes”. The key word here is “pulls”, as it describes a "just-in-time" strategy adopted with this supplier. What is the syntax used by SCOR to represent a pull-mode supply? The Source process descriptions in SCOR 8.0 offers a description that resonates well with the needs of the example: S2 “Source Make-to-Order Product”.

Lastly, the distribution strategy chosen by the manufacturing company is “Ship weekly finished goods to a Distribution Warehouse based in Central Europe”. The description suggests that a weekly shipment is closer to a forecast-based rather than a just-in-time policy. A shipment is a delivery process, so we must look under the “Deliver” tree. By browsing the Level 2 processes in the model we must look for a process configuration that corresponds to the forecast-based policy. We find that in D1 “Deliver Stocked Product”.

The SCOR paradigm demands that whenever a unit of the chain supplies, there must be some other unit that delivers. Similarly, any delivery process requires a correspondent supply process at the other end of the link. So the mapping of the processes of the supply chain is completed, and can be depicted as in the following illustration.

We see now that we don’t need any more the descriptions in the boxes. By just reading the SCOR syntax we immediately capture the salient processes that occur in this chain.

The syntax of the model allows “to speak the same language”. As a matter of fact, if we were to use the “orthodox” representation of a SCOR mapping, we would build a “thread diagram” like the one in the below picture. This is perfectly correspondent to the initial geographical picture, but it contains much more embedded information (we can call it a meta-model) in a more structured and elegant way. The arrows themselves represent the direction of the material flow.

References

- ↑ Poluha, Rolf G. Application of the SCOR model in supply chain management. Cambria Press, 2007.

- ↑ Douglas M. Lambert. Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance. 2008, p. 305.

- ↑ Peter Bolstorff, Robert G. Rosenbaum (2012). Supply Chain Excellence: A Handbook for Dramatic Improvement Using the SCOR. p. 9

- ↑ L. Puigjaner, A. Espuña (2005). European Symposium on Computer-Aided Process Engineering-15. p. 1234.

- ↑ James B. Ayers (2006). Handbook of Supply Chain Management, Second Edition. p. 263

- ↑ W. Benton (2013) Supply Chain Focused Manufacturing Planning and Control. p. 291

- ↑ Roland Zimmermann (2006), Agent-based Supply Network Event Management. p. 58.

- ↑ Luis M. Camarinha-Matos, Iraklis Paraskakis, Hamideh Afsarmanesh (2009). Leveraging Knowledge for Innovation in Collaborative Networks. p. 112

- ↑ Wojciech Syrzysko (2006). Supply Chain Controlling: Integration von APS und SCOR Modell. p.33

Further reading

- Peter Bolstorff, Robert Rosenbaum (2003). Supply Chain Excellence: A Handbook for Dramatic Improvement Using the SCOR Model. AMACOM Div American Mgmt Assn. ISBN 0-8144-0730-7.

- Rolf G. Poluha: Application of the SCOR Model in Supply Chain Management. Youngstown, New York 2007, ISBN 1-934043-23-0.

- D. Simchi-Levi, P. Kaminski, E. Simchi-Levi (2008). Designing and Managing the Supply Chain: Concepts, Strategies and Case Studies. McGraw-Hill International. ISBN 978-0-07-127097-7.

- Shreekant W Shiralkar, Amol Palekar (2012). Supply Chain Analytics With SAP NetWeaver Business Warehouse. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-1-25-900608-1.

- Sherman, Richard J. “Collaborative Planning, Forecasting & Replenishment (CPFR): Realizing the Promise of Efficient Consumer Response through Collaborative Technology,” Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, vol. 6, no. 4 (Fall 1998)