Supervolcano

A supervolcano is any volcano capable of producing a volcanic eruption with an ejecta volume greater than 1,000 km3 (240 cu mi). This is thousands of times larger than normal volcanic eruptions.[1] Supervolcanoes can occur when magma in the mantle rises into the crust from a hotspot but is unable to break through the crust, and pressure builds in a large and growing magma pool until the crust is unable to contain the pressure (this is the case for the Yellowstone Caldera). They can also form at convergent plate boundaries (for example, Toba).

Although there are only a handful of Quaternary supervolcanoes, supervolcanic eruptions typically cover huge areas with lava and volcanic ash and cause a long-lasting change to weather (such as the triggering of a small ice age) sufficient to threaten species with extinction.

Terminology

The origin of the term "supervolcano" is linked to an early 20th-century scientific debate about the geological history and features of the Three Sisters volcanic region of Oregon, United States. In 1925, Edwin T. Hodge suggested that a very large volcano, which he named Mount Multnomah, had existed in that region. He believed that several peaks in the Three Sisters area are the remnants left after Mount Multnomah had been largely destroyed by violent volcanic explosions, similar to Mount Mazama.[2] In 1948, the possible existence of Mount Multnomah was ignored by volcanologist Howel Williams in his book The Ancient Volcanoes of Oregon. The book was reviewed in 1949 by another volcano scientist, F. M. Byers Jr.[3] In the review, Byers refers to Mount Multnomah as a supervolcano.[4] Although Hodge's suggestion that Mount Multnomah is a supervolcano was rejected long ago, the term "supervolcano" was popularised by the BBC popular science television program Horizon in 2000 to refer to eruptions that produce extremely large amounts of ejecta.[5][6]

Volcanologists and geologists do not refer to "supervolcanoes" in their scientific work, since this is a blanket term that can be applied to a number of different geological conditions. Since 2000, however, the term has been used by professionals when presenting to the public. The term megacaldera is sometimes used for caldera supervolcanoes, such as the Blake River Megacaldera Complex in the Abitibi greenstone belt of Ontario and Quebec, Canada. Eruptions that rate VEI 8 are termed "super eruptions".[7]

Though there is no well-defined minimum explosive size for a "supervolcano", there are at least two types of volcanic eruption that have been identified as supervolcanoes: large igneous provinces and massive eruptions.

Large igneous provinces

Large igneous provinces (LIP) such as Iceland, the Siberian Traps, Deccan Traps, and the Ontong Java Plateau are extensive regions of basalts on a continental scale resulting from flood basalt eruptions. When created, these regions often occupy several thousand square kilometres and have volumes on the order of millions of cubic kilometers. In most cases, the lavas are normally laid down over several million years. They release large amounts of gases. The Réunion hotspot produced the Deccan Traps about 66 million years ago, coincident with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. The scientific consensus is that a meteor impact was the cause of the extinction event, but the volcanic activity may have caused environmental stresses on extant species up to the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary. Additionally, the largest flood basalt event (the Siberian Traps) occurred around 250 million years ago and was coincident with the largest mass extinction in history, the Permian–Triassic extinction event, although it is also unknown whether it was completely responsible for the extinction event.

Such outpourings are not explosive though fire fountains may occur. Many volcanologists consider that Iceland may be a LIP that is currently being formed. The last major outpouring occurred in 1783–84 from the Laki fissure which is approximately 40 km (25 mi) long. An estimated 14 km3 (3.4 cu mi) of basaltic lava was poured out during the eruption.

The Ontong Java Plateau now has an area of about 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi), and the province was at least 50% larger before the Manihiki and Hikurangi Plateaus broke away.

Massive explosive eruptions

Volcanic eruptions are classified using the Volcanic Explosivity Index, or VEI.

VEI – 8 eruptions are colossal events that throw out at least 1,000 km3 (240 cu mi) Dense Rock Equivalent (DRE) of ejecta.

VEI – 7 events eject at least 100 cubic kilometres (24 cu mi) DRE.

VEI – 7 or 8 eruptions are so powerful that they often form circular calderas rather than cones because the downward withdrawal of magma causes the overlying mass to collapse and fill the void magma chamber beneath.

One of the classic calderas is at Glen Coe in the Grampian Mountains of Scotland. First described by Clough et al. (1909)[8] its geology and volcanic succession have recently been re-analysed in the light of new discoveries.[9] There is an accompanying 1:25000 solid geology map.

By way of comparison, the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption was a VEI-5 with 1.2 km3 of ejecta.

Both Mount Pinatubo in 1991 and Krakatoa in 1883 were VEI-6 with 10 and 25 km3 (2.4 and 6.0 cu mi) DRE, respectively. The death toll recorded by the Dutch authorities in 1883 was 36,417, although some sources put the estimate at more than 120,000 deaths.

Known supereruptions

VEI 9

The Eruptions at the Paraná and Etendeka traps during the Cretaceous period when taken together are well over 15,000 km³, and may have been a single event that was the largest explosion during the Phanerozoic Eon.

VEI 8

| Name | Zone | Location | Notes | Years ago (approx.) | Ejecta volume (approx.) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Garita Caldera | US, Colorado | Source of the Fish Canyon Tuff, may have been a VEI 9. | 27,800,000 | 5,000 km³ | ||

| Lake Toba | Lake Toba | Indonesia / Sumatra | The disputed[10] Toba catastrophe theory (if true, could have eradicated 60% of human population) | 74,000 | 2,800 km³ | [10][11][12][13][14] |

| Huckleberry Ridge eruption | Yellowstone Hotspot | US, Idaho / Wyoming | Huckleberry Ridge Tuff | 2,100,000 | 2,500 km³ | [15] |

| Atana Ignimbrite | Pacana Caldera | Chile, Northern | 4,000,000 | 2,500 km³ | [16] | |

| Whakamaru | Taupo Volcanic Zone, | New Zealand, North Island | Whakamaru Ignimbrite/Mount Curl Tephra | 254,000 | 2,000 km³ | [17] |

| Heise Volcanic Field | Yellowstone Hotspot | US, Idaho | Kilgore Tuff | 4,500,000 | 1,800 km³. | [18] |

| Heise Volcanic Field | Yellowstone Hotspot | US, Idaho | Blacktail Tuff | 6,000,000 | 1,500 km³. | [18] |

| Lake Taupo | Taupo Volcanic Zone | New Zealand, North Island | Oruanui eruption | 26,500 | 1,170 km³ | |

| Cerro Galan | Argentina, Catamarca Province | 2,500,000 | 1,050 km³ | |||

| Lava Creek eruption | Yellowstone Hotspot | US, Wyoming | Lava Creek Tuff | 640,000 | 1,000 km³ | [15] |

VEI 7

VEI-7 volcanic events, less colossal but still supermassive, have occurred in the geological past. The only ones in historic times are Tambora, in 1815, Lake Taupo, Hatepe, around AD 180,[19] and possibly Baekdu Mountain, AD 969 ± 20 years[20] and the Minoan eruption of Santorini.

| Name | Zone | Location | Event / notes | Years Ago (Approx.) | Ejecta Volume (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Tambora | Sumbawa Island, West Nusa Tenggara | Indonesia | This eruption took place in 1815. The following year, 1816, became known as the Year Without a Summer. | 199 | 160 km³ |

| Lake Taupo | Taupo Volcanic Zone | New Zealand, North Island | Hatepe eruption AD 181 | 1,800 | 120 km³ [19] |

| Kikai Caldera | Japan, Ryukyu Islands | Kikai Caldera 4,300 BC |

6,300 | 150 km³ | |

| Macauley Island | Kermadec Islands | New Zealand | Macauley Island 8,300 to 6,300 years ago | 6,300 | 100 km³ [21][22] |

| Kurile Lake | Kamchatka Peninsula | Russia | Kurile Lake 6,440 BC |

10,500 | 140–170 km³ .[23] |

| Aira Caldera | Japan, Kyūshū | Aira Caldera | 22,000 | 110 km³ | |

| Rotoiti Ignimbrite | Taupo Volcanic Zone | New Zealand, North Island | Rotoiti Ignimbrite | 50,000 | 240 km³ [24] |

| Campi Flegrei | Italy, Naples | 39,280 | 500 km³ | ||

| Mount Aso | Japan, Kyūshū | Four large explosive eruptions between 300,000 to 80,000 years ago. | 300,000 | 600 km³ | |

| Reporoa Caldera | Taupo Volcanic Zone | New Zealand, North Island | 230,000 | 100 km³ [25] | |

| Mamaku Ignimbrite | Taupo Volcanic Zone | New Zealand, North Island | Rotorua Caldera | 240,000 | 280 km³ [26] |

| Matahina Ignimbrite | Taupo Volcanic Zone | New Zealand, North Island | Haroharo Caldera | 280,000 | 120 km³ [27] |

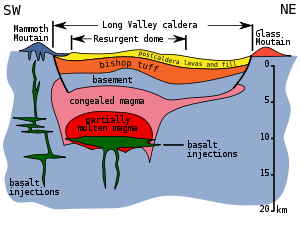

| Long Valley Caldera | Bishop Tuff | USA, California | 760,000 | 600 km³ | |

| Valles Caldera | USA, New Mexico | Two eruptions at 1.15 and 1.47 million years ago | 1,150,000 [28] |

600 km³ [28] | |

| Mangakino | Taupo Volcanic Zone | New Zealand, North Island | Three eruptions from 0.97 to 1.23 million years ago | 970,000 | 300 km³ [29] |

| Henry's Fork Caldera | Yellowstone Hotspot Mesa Falls Tuff |

USA, Idaho | Yellowstone Hotspot | 1,300,000 | 280 km³ [15] |

| Karymshina | Kamchatka | Russia | 1,780,000 [30] |

>1000 km³ .[31] | |

| Pastos Grandes Ignimbrite | Pastos Grandes Caldera | Bolivia | 2,900,000 | 820 km³ [32] | |

| Heise volcanic field | Yellowstone Hotspot Walcott Tuff |

USA, Idaho | Yellowstone Hotspot | 6,400,000 | 750 km³ [18] |

| Bruneau-Jarbidge | Yellowstone Hotspot | USA, Idaho | Yellowstone Hotspot Responsible for the Ashfall Fossil Beds 1,600 km to the east[33] |

12,000,000 | 250 km³ |

| Bennett Lake Volcanic Complex | Skukum Group | Canada, British Columbia/Yukon | 50,000,000 | 850 km³ [34] |

Ongoing studies

- A hypothetical Campanian ignimbrite super-eruption around 40,000 years ago has been suggested as having contributed to the demise of the Neanderthal, based on evidence from Mezmaiskaya cave in the Caucasus Mountains of southern Russia.[35]

- A Diamond anvil cell simulation at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and computer modeling at the University of Bristol showed that it was possible for a supervolcano eruption to occur simply through the slow addition of liquid magma without any external trigger such as an earthquake that might provide warning of the event.[36][37]

Media portrayal

- In 2004, Naked Science TV show aired supervolcano on National Geographic Channel.

- In 2005, a two-part television docudrama called Supervolcano aired on BBC One, the Discovery Channel, and other television networks worldwide.

- Nova featured an episode "Mystery of the Megavolcano" in September 2006 examining such eruptions in the last 100,000 years.[38]

- In 2006, the Sci Fi Channel aired the documentary Countdown to Doomsday which featured a segment called "Supervolcano". The same year, ABC News aired the documentary Last Days on Earth, which featured a segment called "Supervolcano".

- Also in 2006, the Syfy Channel series Stargate Atlantis episode entitled "Inferno" featured a supervolcano as the major plot device. Dr. Rodney McKay, one of the main characters, uses Yellowstone National Park to describe what a supervolcano is.

- In the episode "Humanity" of the television drama Young Justice, the team must relieve the pressure of the Yellowstone Caldera supervolcano caused by Red Volcano before an eruption with the potential for mass extinction takes place.

- In 2009, the apocalypse-themed film 2012 featured the super-eruption of the massive Yellowstone Caldera, a result of the Earth's core heating up. This made most of the United States uninhabitable.

- In 2010, the SyFy series Warehouse 13 featured an episode entitled Reset in which a supervolcano, specifically the Yellowstone Caldera, plays an important role.

- In December 2011, author Harry Turtledove published Supervolcano: Eruption, the first of a planned four-novel series about events leading up to and following a fictional eruption of the Yellowstone Caldera. The second book in the series, Supervolcano: All Fall Down, was published in December 2012. The third book Supervolcano: Things Fall Apart, was published in December 2013.

- At the end of Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter's novel Long War the Yellowstone Caldera erupts. The aftermath will be featured in the next volume, Long Mars.

See also

- Risks to civilization, humans, and planet Earth

- Toba catastrophe theory

- Timetable of major worldwide volcanic eruptions

- Volcanic winter

References

- ↑ Questions About Super Volcanoes. Volcanoes.usgs.gov (2009-05-08). Retrieved on 2011-11-18.

- ↑ Harris, Stephen (1988) Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes, Missoula, Mountain Press.

- ↑ Byers, Jr., F. M. (1949) Reviews: The Ancient Volcanoes of Oregon by Howel Williams, The Journal of Geology, volume 57, number 3, May 1949, page 324. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ↑ supervolcano, n. Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, online version June 2012. Retrieved on 2012-08-17.

- ↑ Supervolcanoes. Bbc.co.uk (2000-02-03). Retrieved on 2011-11-18.

- ↑ USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory. Vulcan.wr.usgs.gov. Retrieved on 2011-11-18.

- ↑ de Silva, Shanaka (2008). "Arc magmatism, calderas, and supervolcanos". Geology 36 (8): 671–672. doi:10.1130/focus082008.1.

- ↑ Clough, C. T; Maufe, H. B. & Bailey, E. B (1909). "The cauldron subsidence of Glen Coe, and the Associated Igneous Phenomena". Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc. 65: 611–678. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1909.065.01-04.35.

- ↑ Kokelaar, B. P and Moore, I. D; 2006. Glencoe caldera volcano, Scotland. British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham. ISBN 0-85272-525-6.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Petraglia, M.; Korisettar, R.; Boivin, N.; Clarkson, C.; Ditchfield, P.; Jones, S.; Koshy, J.; Lahr, M. M. et al. (2007). "Middle Paleolithic Assemblages from the Indian Subcontinent Before and After the Toba Super-Eruption". Science 317 (5834): 114–6. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..114P. doi:10.1126/science.1141564. PMID 17615356.

- ↑ Knight, M.D., Walker, G.P.L., Ellwood, B.B., and Diehl, J.F. (1986). "Stratigraphy, paleomagnetism, and magnetic fabric of the Toba Tuffs: Constraints on their sources and eruptive styles". Journal of Geophysical Research 91: 10355–10382. Bibcode:1986JGR....9110355K. doi:10.1029/JB091iB10p10355.

- ↑ Ninkovich, D., Sparks, R.S.J., and Ledbetter, M.T. (1978). "The exceptional magnitude and intensity of the Toba eruption, Sumatra: An example of using deep-sea tephra layers as a geological tool". Bulletin Volcanologique 41 (3): 286–298. Bibcode:1978BVol...41..286N. doi:10.1007/BF02597228.

- ↑ Rose, W.I., and Chesner, C.A. (1987). "Dispersal of ash in the great Toba eruption, 75 ka" (PDF). Geology 15 (10): 913–917. Bibcode:1987Geo....15..913R. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1987)15<913:DOAITG>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.; Lee Siebert, Tom Simkin, Paul Kimberly Volcanoes of the World. University of California Press, 2011 ISBN 0-520-26877-6

- ↑ Williams, M.A.J., and Royce, K. (1982). "Quaternary geology of the middle son valley, North Central India: Implications for prehistoric archaeology". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 38 (3–4): 139. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(82)90001-3.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Global Volcanism Program | Volcanoes of the World | Large Holocene Eruptions. Volcano.si.edu. Retrieved on 2011-11-18.

- ↑ Lindsay, J. M.; de Silva, S.; Trumbull, R.; Emmermann, R.; Wemmer, K. (2001). "La Pacana caldera, N. Chile: a re-evaluation of the stratigraphy and volcanology of one of the world's largest resurgent calderas". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 106 (1–2): 145–173. Bibcode:2001JVGR..106..145L. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(00)00270-5.

- ↑ Froggatt, P. C.; Nelson, C. S.; Carter, L.; Griggs, G.; Black, K. P. (13 February 1986). "An exceptionally large late Quaternary eruption from New Zealand". Nature 319 (6054): 578–582. Bibcode:1986Natur.319..578F. doi:10.1038/319578a0.

The minimum total volume of tephra is 1,200 km³ but probably nearer 2,000 km³, ...

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Lisa A. Morgan and William C. McIntosh (2005). "Timing and development of the Heise volcanic field, Snake River Plain, Idaho, western USA". GSA Bulletin 117 (3–4): 288–306. Bibcode:2005GSAB..117..288M. doi:10.1130/B25519.1.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Wilson, C. J. N.; Ambraseys, N. N.; Bradley, J.; Walker, G. P. L. (1980). "A new date for the Taupo eruption, New Zealand". Nature 288 (5788): 252–253. Bibcode:1980Natur.288..252W. doi:10.1038/288252a0.

- ↑ Horn, Susanne; Schmincke, Hans-Ulrich (2000). "Volatile emission during the eruption of Baitoushan Volcano (China/North Korea) ca. 969 CE". Bulletin of Volcanology 61 (8): 537–555. doi:10.1007/s004450050004.

The 969±20 CE Plinian eruption of Baitoushan Volcano (China/North Korea) produced a total tephra volume of 96±19 km³ [magma volume (DRE): 24±5 km³].

- ↑ Latter, J. H.; Lloyd, E. F.; Smith, I. E. M.; Nathan, S. 1992. Volcanic hazards in the Kermadec Islands and at submarine volcanoes between southern Tonga and New Zealand, Volcanic hazards information series 4. Wellington, New Zealand. Ministry of Civil Defence. 44 p.

- ↑ "Macauley Island". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑

- ↑ Froggatt, P. C. and Lowe, D. J. (1990). "A review of late Quaternary silicic and some other tephra formations from New Zealand: their stratigraphy, nomenclature, distribution, volume, and age". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 33: 89–109. doi:10.1080/00288306.1990.10427576.

- ↑ I. A. Nairn; C. P. Wood and R. A. Bailey (December 1994). "The Reporoa Caldera, Taupo Volcanic Zone: source of the Kaingaroa Ignimbrites". Bulletin of Volcanology 56 (6): 529–537. Bibcode:1994BVol...56..529N. doi:10.1007/BF00302833. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ Karl D. Spinks, J.W. Cole, & G.S. Leonard 2004. Caldera Volcanism in the Taupo Volcanic Zone. In: Manville, V.R. | ed. Geological Society of New Zealand/New Zealand Geophysical Society/26th New Zealand Geothermal Workshop, 6–9 December 2004, Taupo: field trip guides. Geological Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 117B.

- ↑ Bailey, R. A. and Carr, R. G. (1994). "Physical geology and eruptive history of the Matahina Ignimbrite, Taupo Volcanic Zone, North Island, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 37 (3): 319–344. doi:10.1080/00288306.1994.9514624.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Izett, Glen A. (1981). "Volcanic Ash Beds: Recorders of Upper Cenozoic Silicic Pyroclastic Volcanism in the Western United States". Journal of Geophysical Research 86 (B11): 10200–10222. Bibcode:1981JGR....8610200I. doi:10.1029/JB086iB11p10200.

- ↑ Briggs, R.M.; Gifford, M.G.; Moyle, A.R.; Taylor, S.R.; Normaff, M.D.; Houghton, B.F.; Wilson, C.J.N. (1993). "Geochemical zoning and eruptive mixing in ignimbrites from Mangakino volcano, Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 56 (3): 175–203. Bibcode:1993JVGR...56..175B. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(93)90016-K.

- ↑ Shipley, Niccole; Bindeman, Ilya; Leonov, Vladimir (18–21 October 2009). "Petrologic and Isotopic Investigation of Rhyolites from Karymshina Caldera, the Largest "Super"caldera in Kamchatka, Russia". Portland GSA Annual Meeting.

- ↑

- ↑ Ort, M. H.; de Silva, S.; Jiminez, N.; Salisbury, M.; Jicha, B. R. and Singer, B. S. Two new supereruptions in the Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex of the Central Andes. Portland GSA Annual Meeting, 18–21 October 2009

- ↑ Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park. "The Ashfall Story". Retrieved 8 August 2006.

- ↑ Lambert, Maurice B. (1978). Volcanoes. North Vancouver, British Columbia: Energy, Mines and Resources Canada. ISBN 0-88894-227-3.

- ↑ Golovanova, Liubov Vitaliena; Doronichev, Vladimir Borisovich; Cleghorn, Naomi Elansia; Koulkova, Marianna Alekseevna; Sapelko, Tatiana Valentinovna; Shackley, M. Steven (2010). "Significance of Ecological Factors in the Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transition". Current Anthropology 51 (5): 655. doi:10.1086/656185.

- ↑ Morgan, James (5 January 2014). "Supervolcano eruption mystery solved". www.bbc.co.uk. The BBC. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ Sample, Ian (6 January 2014). "Geologists identify trigger for apocalyptic 'super eruptions'". www.theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ Mystery of the Megavolcano. Pbs.org. Retrieved on 2011-11-18.

Further reading

- Mason, Ben G.; Pyle, David M.; Oppenheimer, Clive (2004). "The size and frequency of the largest explosive eruptions on Earth". Bulletin of Volcanology 66 (8): 735–748. Bibcode:2004BVol...66..735M. doi:10.1007/s00445-004-0355-9.

- Oppenheimer, C. (2011). Eruptions that shook the world. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64112-8.

- Timmreck, C.; Graf, H.-F. (2006). "The initial dispersal and radiative forcing of a Northern Hemisphere mid-latitude super volcano: a model study". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 6: 35–49. doi:10.5194/acp-6-35-2006.

External links

- Overview and Transcript of the original BBC program

- Yellowstone Supervolcano and Map of Supervolcanoes Around The World

- USGS Fact Sheet – Steam Explosions, Earthquakes, and Volcanic Eruptions – What's in Yellowstone's Future?

- Scientific American's The Secrets of Supervolcanoes

- Supervolcano eruption mystery solved, BBC Science, 6 January 2014

| |||||||||||||||||||||