Sum of normally distributed random variables

In probability theory, calculation of the sum of normally distributed random variables is an instance of the arithmetic of random variables, which can be quite complex based on the probability distributions of the random variables involved and their relationships.

Independent random variables

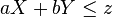

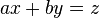

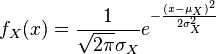

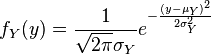

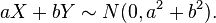

If X and Y are independent random variables that are normally distributed, then their sum is also normally distributed. i.e., if

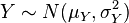

,

,

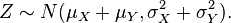

then

This means that the sum of two independent normally distributed random variables is normal, with its mean being the sum of the two means, and its variance being the sum of the two variances (i.e., the square of the standard deviation is the sum of the squares of the standard deviations).

Note that the result that the sum is normally distributed requires the assumption of independence, not just uncorrelatedness; two separately (not jointly) normally distributed random variables can be uncorrelated without being independent, in which case their sum can be non-normally distributed (see Normally distributed and uncorrelated does not imply independent#A symmetric example). The result about the mean holds in all cases, while the result for the variance requires uncorrelatedness, but not independence.

Proofs

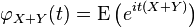

Proof using characteristic functions

of the sum of two independent random variables X and Y is just the product of the two separate characteristic functions:

of X and Y.

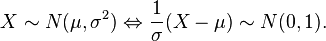

The characteristic function of the normal distribution with expected value μ and variance σ2 is

So

This is the characteristic function of the normal distribution with expected value  and variance

and variance

Finally, recall that no two distinct distributions can both have the same characteristic function, so the distribution of X+Y must be just this normal distribution.

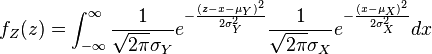

Proof using convolutions

For independent random variables X and Y, the distribution fZ of Z = X+Y equals the convolution of fX and fY:

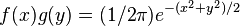

Given that fX and fY are normal densities,

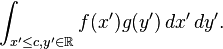

Substituting into the convolution:

The expression in the integral is a normal density distribution on x, and so the integral evaluates to 1. The desired result follows:

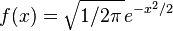

Geometric proof

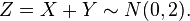

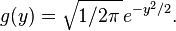

First consider the normalized case when X, Y ~ N(0, 1), so that their PDFs are

and

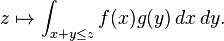

Let Z = X+Y. Then the CDF for Z will be

This integral is over the half-plane which lies under the line x+y = z.

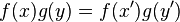

The key observation is that the function

is radially symmetric. So we rotate the coordinate plane about the origin, choosing new coordinates  such that the line x+y = z is described by the equation

such that the line x+y = z is described by the equation  where

where  is determined geometrically. Because of the radial symmetry, we have

is determined geometrically. Because of the radial symmetry, we have  , and the CDF for Z is

, and the CDF for Z is

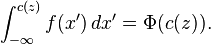

This is easy to integrate; we find that the CDF for Z is

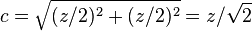

To determine the value  , note that we rotated the plane so that the line x+y = z now runs vertically with x-intercept equal to c. So c is just the distance from the origin to the line x+y = z along the perpendicular bisector, which meets the line at its nearest point to the origin, in this case

, note that we rotated the plane so that the line x+y = z now runs vertically with x-intercept equal to c. So c is just the distance from the origin to the line x+y = z along the perpendicular bisector, which meets the line at its nearest point to the origin, in this case  . So the distance is

. So the distance is  , and the CDF for Z is

, and the CDF for Z is  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

Now, if a, b are any real constants (not both zero!) then the probability that  is found by the same integral as above, but with the bounding line

is found by the same integral as above, but with the bounding line  . The same rotation method works, and in this more general case we find that the closest point on the line to the origin is located a (signed) distance

. The same rotation method works, and in this more general case we find that the closest point on the line to the origin is located a (signed) distance

away, so that

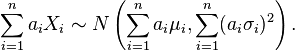

The same argument in higher dimensions shows that if

then

Now we are essentially done, because

So in general, if

then

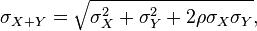

Correlated random variables

In the event that the variables X and Y are jointly normally distributed random variables, then X + Y is still normally distributed (see Multivariate normal distribution) and the mean is the sum of the means. However, the variances are not additive due to the correlation. Indeed,

where ρ is the correlation. In particular, whenever ρ < 0, then the variance is less than the sum of the variances of X and Y.

Extensions of this result can be made for more than two random variables, using the covariance matrix.

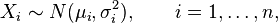

Proof

In this case, one needs to consider

As above, one makes the substitution

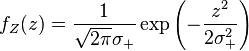

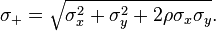

This integral is more complicated to simplify analytically, but can be done easily using a symbolic mathematics program. The probability distribution fZ(z) is given in this case by

where

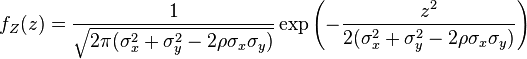

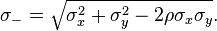

If one considers instead Z = X − Y, then one obtains

which also can be rewritten with

The standard deviations of each distribution are obvious by comparison with the standard normal distribution.

See also

- Algebra of random variables

- Stable distribution

- Standard error (statistics)

- Ratio distribution

- Product distribution

- Slash distribution

- List of convolutions of probability distributions

- Not to be confused with: Mixture distribution

![= \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sqrt{\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2}} \exp \left[ - { (z-(\mu_X+\mu_Y))^2 \over 2(\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2) } \right] \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\frac{\sigma_X\sigma_Y}{\sqrt{\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2}}} \exp \left[ - \frac{\left(x-\frac{\sigma_X^2(z-\mu_Y)+\sigma_Y^2\mu_X}{\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2}\right)^2}{2\left(\frac{\sigma_X\sigma_Y}{\sqrt{\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2}}\right)^2} \right] dx](../I/m/27d22c05c194a833d63be0b3ccf4ad2f.png)

![= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi(\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2)}} \exp \left[ - { (z-(\mu_X+\mu_Y))^2 \over 2(\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2) } \right] \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\frac{\sigma_X\sigma_Y}{\sqrt{\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2}}} \exp \left[ - \frac{\left(x-\frac{\sigma_X^2(z-\mu_Y)+\sigma_Y^2\mu_X}{\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2}\right)^2}{2\left(\frac{\sigma_X\sigma_Y}{\sqrt{\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2}}\right)^2} \right] dx](../I/m/99541e42ff3fe3cbc72f798c46d5f20d.png)

![f_Z(z) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi(\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2)}} \exp \left[ - { (z-(\mu_X+\mu_Y))^2 \over 2(\sigma_X^2+\sigma_Y^2) } \right]](../I/m/aacf5f4703fa1428151a965291a5b5c8.png)

![\frac{1}{2 \pi \sigma_x \sigma_y \sqrt{1-\rho^2}} \iint_{x\,y} \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2(1-\rho^2)} \left(\frac{x^2}{\sigma_x^2} + \frac{y^2}{\sigma_y^2} - \frac{2 \rho x y}{\sigma_x\sigma_y}\right)\right] \delta(z - (x+y))\, \operatorname{d}x\,\operatorname{d}y.](../I/m/0438b3015d31d53c1a833f80d700bc6c.png)