Subadditivity

In mathematics, subadditivity is a property of a function that states, roughly, that evaluating the function for the sum of two elements of the domain always returns something less than or equal to the sum of the function's values at each element. There are numerous examples of subadditive functions in various areas of mathematics, particularly norms and square roots. Additive maps are special cases of subadditive functions.

Definitions

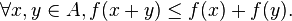

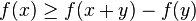

A subadditive function is a function  , having a domain A and an ordered codomain B that are both closed under addition, with the following property:

, having a domain A and an ordered codomain B that are both closed under addition, with the following property:

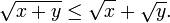

An example is the square root function, having the non-negative real numbers as domain and codomain,

since  we have:

we have:

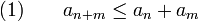

A sequence  , is called subadditive if it satisfies the inequality

, is called subadditive if it satisfies the inequality

for all m and n.

Properties

A useful result pertaining to subadditive sequences is the following lemma due to Michael Fekete.[1]

- Fekete's Subadditive Lemma: For every subadditive sequence

, the limit

, the limit  exists and is equal to

exists and is equal to  . (The limit may be

. (The limit may be  .)

.)

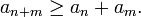

The analogue of Fekete's lemma holds for superadditive functions as well, that is:

(The limit then may be positive infinity: consider the sequence

(The limit then may be positive infinity: consider the sequence  .)

.)

There are extensions of Fekete's lemma that do not require the inequality (1) to hold for all m and n. There are also results that allow one to deduce the rate of convergence to the limit whose existence is stated in Fekete's lemma if some kind of both superadditivity and subadditivity is present.[2][3]

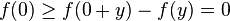

If f is a subadditive function, and if 0 is in its domain, then f(0) ≥ 0. To see this, take the inequality at the top.  . Hence

. Hence

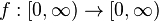

A concave function  with

with  is also subadditive.

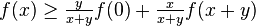

To see this, one first observes that

is also subadditive.

To see this, one first observes that  .

Then looking at the sum of this bound for

.

Then looking at the sum of this bound for  and

and  , will finally verify that f is subadditive.[4]

, will finally verify that f is subadditive.[4]

The negative of a subadditive function is superadditive.

Economics

Subadditivity is an essential property of some particular cost functions. It is, generally, a necessary and sufficient condition for the verification of a natural monopoly. It implies that production from only one firm is socially less expensive (in terms of average costs) than production of a fraction of the original quantity by an equal number of firms.

Economies of scale are represented by subadditive average cost functions.

Except in the case of complementary goods, the price of goods (as a function of quantity) must be subadditive. Otherwise, if the sum of the cost of two items is cheaper than the cost of the bundle of two of them together, then nobody would ever buy the bundle, effectively causing the price of the bundle to "become" the sum of the prices of the two separate items. Thus proving that it is not a sufficient condition for a natural monopoly; since the unit of exchange may not be the actual cost of an item. This situation is familiar to everyone in the political arena where some minority asserts that the loss of some particular freedom at some particular level of government means that many governments are better; whereas the majority assert that there is some other correct unit of cost.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Fekete, M. (1923). "Über die Verteilung der Wurzeln bei gewissen algebraischen Gleichungen mit ganzzahligen Koeffizienten". Mathematische Zeitschrift 17 (1): 228–249. doi:10.1007/BF01504345.

- ↑ Michael J. Steele. "Probability theory and combinatorial optimization". SIAM, Philadelphia (1997). ISBN 0-89871-380-3.

- ↑ Michael J. Steele (2011). CBMS Lectures on Probability Theory and Combinatorial Optimization. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Schechter, Eric (1997). Handbook of Analysis and its Foundations. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-622760-8., p.314,12.25

References

- György Pólya and Gábor Szegő. "Problems and theorems in analysis, volume 1". Springer-Verlag, New York (1976). ISBN 0-387-05672-6.

External links

This article incorporates material from subadditivity on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.