Stress relaxation

In materials science, stress relaxation is the observed decrease in stress in response to the same amount of strain generated in the structure. This is primarily due to keeping the structure in a strained condition for some finite interval of time and hence causing some amount of plastic strain. This should not be confused with creep, which is a constant state of stress with an increasing amount of strain.

Since relaxation relieves the state of stress, it has the effect of also relieving the equipment reactions. Thus, relaxation has the same effect as cold springing, except it occurs over a longer period of time. The amount of relaxation which takes place is a function of time, temperature and stress level, thus the actual effect it has on the system is not precisely known, but can be bounded.

Stress relaxation describes how polymers relieve stress under constant strain. Because they are viscoelastic, polymers behave in a nonlinear, non-Hookean fashion.[1] This nonlinearity is described by both stress relaxation and a phenomenon known as creep, which describes how polymers strain under constant stress.

Viscoelastic materials have the properties of both viscous and elastic materials and can be modeled by combining elements that represent these characteristics. One viscoelastic model, called the Maxwell model predicts behavior akin to a spring (elastic element) being in series with a dashpot (viscous element), while the Voigt model places these elements in parallel. Although the Maxwell model is good at predicting stress relaxation, it is fairly poor at predicting creep. On the other hand, the Voigt model is good at predicting creep but rather poor at predicting stress relaxation (see Viscoelasticity).

The following image shows the response of a Standard Linear Solid material to a constant stress,  , over time from

, over time from  to a later time

to a later time  . For times greater than

. For times greater than  the load is removed. The curvature of the model represent the effects of both creep and stress relaxation.

the load is removed. The curvature of the model represent the effects of both creep and stress relaxation.

Stress relaxation calculations can differ for different materials:

To generalize, Obukhov uses power dependencies:[2]

where  is the maximum stress at the time the loading was removed (t*), and n is a material parameter.

is the maximum stress at the time the loading was removed (t*), and n is a material parameter.

Vegener et al. use a power series to describe stress relaxation in polyamides:[2]

![\sigma(t)= \sum_{mn}^{} { A_{mn} [\ln(1+t)]^m (\epsilon'_0)^n}](../I/m/9c5f25c1033e48ca7cc7b8f97464bfdd.png)

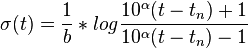

To model stress relaxation in glass materials Dowvalter uses the following:[2]

where

where  is a material constant and b and

is a material constant and b and  depend on processing conditions.

depend on processing conditions.

The following non-material parameters all affect stress relaxation in polymers :[2]

- Magnitude of initial loading

- Speed of loading

- Temperature (isothermal vs non-isothermal conditions)

- Loading medium

- Friction and wear

- Long-term storage

See also

- Creep

- Viscoelasticity

- Standard Linear Solid Model

- Maxwell material

- Kelvin–Voigt material

![\sigma(t)= \frac { \sigma_0 }{ 1-[1-(t/t*)(1^{1-n})]}](../I/m/7e150056e16906023f6ce0218bc27e05.png)