Strengthening mechanisms of materials

Methods have been devised to modify the yield strength, ductility, and toughness of both crystalline and amorphous materials. These strengthening mechanisms give engineers the ability to tailor the mechanical properties of materials to suit a variety of different applications. For example, the favorable properties of steel result from interstitial incorporation of carbon into the iron lattice. Brass, a binary alloy of copper and zinc, has superior mechanical properties compared to its constituent metals due to solution strengthening. Work hardening (such as beating a red-hot piece of metal on anvil) has also been used for centuries by blacksmiths to introduce dislocations into materials, increasing their yield strengths.

What strengthening is

Plastic deformation occurs when large numbers of dislocations move and multiply so as to result in macroscopic deformation. In other words, it is the movement of dislocations in the material which allows for deformation. If we want to enhance a material's mechanical properties (i.e. increase the yield and tensile strength), we simply need to introduce a mechanism which prohibits the mobility of these dislocations. Whatever the mechanism may be, (work hardening, grain size reduction, etc.) they all hinder dislocation motion and render the material stronger than previously.[1][2][3][4]

The stress required to cause dislocation motion is orders of magnitude lower than the theoretical stress required to shift an entire plane of atoms, so this mode of stress relief is energetically favorable. Hence, the hardness and strength (both yield and tensile) critically depend on the ease with which dislocations move. Pinning points, or locations in the crystal that oppose the motion of dislocations,[5] can be introduced into the lattice to reduce dislocation mobility, thereby increasing mechanical strength. Dislocations may be pinned due to stress field interactions with other dislocations and solute particles, creating physical barriers from second phase precipitates forming along grain boundaries. There are four main strengthening mechanisms for metals, each is a method to prevent dislocation motion and propagation, or make it energetically unfavorable for the dislocation to move. For a material that has been strengthened, by some processing method, the amount of force required to start irreversible (plastic) deformation is greater than it was for the original material.

In amorphous materials such as polymers, amorphous ceramics (glass), and amorphous metals, the lack of long range order leads to yielding via mechanisms such as brittle fracture, crazing, and shear band formation. In these systems, strengthening mechanisms do not involve dislocations, but rather consist of modifications to the chemical structure and processing of the constituent material.

The strength of materials cannot infinitely increase. Each of the mechanisms explained below involves some trade-off by which other material properties are compromised in the process of strengthening.

Strengthening mechanisms in metals

Work hardening

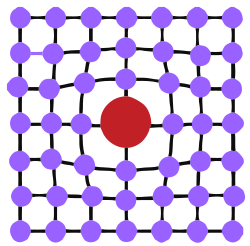

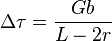

The primary species responsible for work hardening are dislocations. Dislocations interact with each other by generating stress fields in the material. The interaction between the stress fields of dislocations can impede dislocation motion by repulsive or attractive interactions. Additionally, if two dislocations cross, dislocation line entanglement occurs, causing the formation of a jog which opposes dislocation motion. These entanglements and jogs act as pinning points, which oppose dislocation motion. As both of these processes are more likely to occur when more dislocations are present, there is a correlation between dislocation density and yield strength,

where  is the shear modulus,

is the shear modulus,  is the Burgers vector, and

is the Burgers vector, and  is the dislocation density.

is the dislocation density.

Increasing the dislocation density increases the yield strength which results in a higher shear stress required to move the dislocations. This process is easily observed while working a material (in metals cold working of process). Theoretically, the strength of a material with no dislocations will be extremely high (τ=G/2) because plastic deformation would require the breaking of many bonds simultaneously. However, at moderate dislocation density values of around 107-109 dislocations/m2, the material will exhibit a significantly lower mechanical strength. Analogously, it is easier to move a rubber rug across a surface by propagating a small ripple through it than by dragging the whole rug. At dislocation densities of 1014 dislocations/m2 or higher, the strength of the material becomes high once again. Also, the dislocation density cannot be infinitely high, because then the material would lose its crystalline structure.

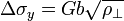

Solid solution strengthening and alloying

For this strengthening mechanism, solute atoms of one element are added to another, resulting in either substitutional or interstitial point defects in the crystal (see Figure 1). The solute atoms cause lattice distortions that impede dislocation motion, increasing the yield stress of the material. Solute atoms have stress fields around them which can interact with those of dislocations. The presence of solute atoms impart compressive or tensile stresses to the lattice, depending on solute size, which interfere with nearby dislocations, causing the solute atoms to act as potential barriers \

The shear stress required to move dislocations in a material is:

where  is the solute concentration and

is the solute concentration and  is the strain on the material caused by the solute.

is the strain on the material caused by the solute.

Increasing the concentration of the solute atoms will increase the yield strength of a material, but there is a limit to the amount of solute that can be added, and one should look at the phase diagram for the material and the alloy to make sure that a second phase is not created.

In general, the solid solution strengthening depends on the concentration of the solute atoms, shear modulus of the solute atoms, size of solute atoms, valency of solute atoms (for ionic materials), and the symmetry of the solute stress field. The magnitude of strengthening is higher for non-symmetric stress fields because these solutes can interact with both edge and screw dislocations, whereas symmetric stress fields, which cause only volume change and not shape change, can only interact with edge dislocations.

Precipitation hardening

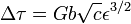

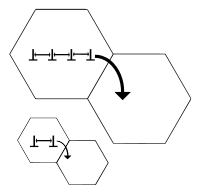

In most binary systems, alloying above a concentration given by the phase diagram will cause the formation of a second phase. A second phase can also be created by mechanical or thermal treatments. The particles that compose the second phase precipitates act as pinning points in a similar manner to solutes, though the particles are not necessarily single atoms.

The dislocations in a material can interact with the precipitate atoms in one of two ways (see Figure 2). If the precipitate atoms are small, the dislocations would cut through them. As a result, new surfaces (b in Figure 2) of the particle would get exposed to the matrix and the particle-matrix interfacial energy would increase. For larger precipitate particles, looping or bowing of the dislocations would occur and result in dislocations getting longer. Hence, at a critical radius of about 5 nm, dislocations will preferably cut across the obstacle, while for a radius of 30 nm, the dislocations will readily bow or loop to overcome the obstacle.

The mathematical descriptions are as follows:

For particle bowing-

For particle cutting-

Grain boundary strengthening

In a polycrystalline metal, grain size has a tremendous influence on the mechanical properties. Because grains usually have varying crystallographic orientations, grain boundaries arise. While undergoing deformation, slip motion will take place. Grain boundaries act as an impediment to dislocation motion for the following two reasons:

1. Dislocation must change its direction of motion due to the differing orientation of grains.[4] 2. Discontinuity of slip planes from grain one to grain two.[4]

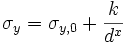

The stress required to move a dislocation from one grain to another in order to plastically deform a material depends on the grain size. The average number of dislocations per grain decreases with average grain size (see Figure 3). A lower number of dislocations per grain results in a lower dislocation 'pressure' building up at grain boundaries. This makes it more difficult for dislocations to move into adjacent grains. This relationship is the Hall-Petch relationship and can be mathematically described as follows:

,

,

where  is a constant,

is a constant,  is the average grain diameter and

is the average grain diameter and  is the original yield stress.

is the original yield stress.

The fact that the yield strength increases with decreasing grain size is accompanied by the caveat that the grain size cannot be decreased infinitely. As the grain size decreases, more free volume is generated resulting in lattice mismatch. Below approximately 10 nm, the grain boundaries will tend to slide instead; a phenomenon known as grain-boundary sliding. If the grain size gets too small, it becomes more difficult to fit the dislocations in the grain and the stress required to move them is less. It was not possible to produce materials with grain sizes below 10 nm until recently, so the discovery that strength decreases below a critical grain size is still finding new applications.

Transformation hardening

This method of hardening is used for steels.

High-strength steels generally fall into three basic categories, classified by the strengthening mechanism employed. 1- solid-solution-strengthened steels (rephos steels) 2- grain-refined steels or high strength low alloy steels (HSLA) 3- transformation-hardened steels

Transformation-hardened steels are the third type of high-strength steels.These steels use predominately higher levels of C and Mn along with heat treatment to increase strength. The finished product will have a duplex microstructure of ferrite with varying levels of degenerate martensite. This allows for varying levels of strength. There are three basic types of transformation-hardened steels. These are dual-phase (DP), transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP),and martensitic steels.

The annealing process for dual -phase steels consists of first holding the steel in the a + gamma temperature region for a set period of time. During that time C and Mn diffuse into the austenite leaving a ferrite of greater purity. The steel is then quenched so that the austenite is transformed into martensite, and the ferrite remains on cooling. The steel is then subjected to a temper cycle to allow some level of martensite decomposition. By controlling the amount of martensite in the steel, as well as the degree of temper, the strength level can be controlled. Depending on processing and chemistry, the strength level can range from 350 to 960 MPa.

TRIP steels also use C and Mn, along with heat treatment, in order to retain small amounts of austenite and bainite in a ferrite matrix. Thermal processing for TRIP steels again involves annealing the steel in the a + g region for a period of time sufficient to allow C and Mn to diffuse into austenite. The steel is then quenched to a point above the martensite start temperature and held there. This allows the formation of bainite, an austenite decomposition product. While at this temperature, more C is allowed to enrich the retained austenite. This, in turn, lowers the martensite start temperature to below room temperature. Upon final quenching a metastable austenite is retained in the predominately ferrite matrix along with small amounts of bainite (and other forms of decomposed austenite). This combination of microstructures has the added benefits of higher strengths and resistance to necking during forming. This offers great improvements in formability over other high-strength steels. Essentially, as the TRIP steel is being formed, it becomes much stronger. Tensile strengths of TRIP steels are in the range of 600-960 MPa.

Martensitic steels are also high in C and Mn. These are fully quenched to martensite during processing. The martensite structure is then tempered back to the appropriate strength level, adding toughness to the steel. Tensile strengths for these steels range as high as 1500 MPa.

Strengthening mechanisms in amorphous materials

Polymer

Polymers fracture via breaking of inter- and intra molecular bonds; hence, the chemical structure of these materials plays a huge role in increasing strength. For polymers consisting of chains which easily slide past each other, chemical and physical cross linking can be used to increase rigidity and yield strength. In thermoset polymers (thermosetting plastic), disulfide bridges and other covalent cross links give rise to a hard structure which can withstand very high temperatures. These cross-links are particularly helpful in improving tensile strength of materials which contain lots of free volume prone to crazing, typically glassy brittle polymers.[6] In thermoplastic elastomer, phase separation of dissimilar monomer components leads to association of hard domains within a sea of soft phase, yielding a physical structure with increased strength and rigidity. If yielding occurs by chains sliding past each other (shear bands), the strength can also be increased by introducing kinks into the polymer chains via unsaturated carbon-carbon bonds.[6]

Increasing the bulkiness of the monomer unit via incorporation of aryl rings is another strengthening mechanism. The anisotropy of the molecular structure means that these mechanisms are heavily dependent on the direction of applied stress. While aryl rings drastically increase rigidity along the direction of the chain, these materials may still be brittle in perpendicular directions. Macroscopic structure can be adjusted to compensate for this anisotropy. For example, the high strength of Kevlar arises from a stacked multilayer macrostructure where aromatic polymer layers are rotated with respect to their neighbors. When loaded oblique to the chain direction, ductile polymers with flexible linkages, such as oriented polyethylene, are highly prone to shear band formation, so macroscopic structures which place the load parallel to the draw direction would increase strength.[6]

Mixing polymers is another method of increasing strength, particularly with materials that show crazing preceding brittle fracture such as atactic polystyrene (APS). For example, by forming a 50/50 mixture of APS with polyphenylene oxide (PPO), this embrittling tendency can be almost completely suppressed, substantially increasing the fracture strength.[6]

Glass

Many silicate glasses are strong in compression but weak in tension. By introducing compression stress into the structure, the tensile strength of the material can be increased. This is typically done via two mechanisms: thermal treatment (tempering) or chemical bath (via ion exchange).

In tempered glasses, air jets are used to rapidly cool the top and bottom surfaces of a softened (hot) slab of glass. Since the surface cools quicker, there is more free volume at the surface than in the bulk melt. The core of the slab then pulls the surface inward, resulting in an internal compressive stress at the surface. This substantially increases the tensile strength of the material as tensile stresses exterted on the glass must now resolve the compressive stresses before yielding.

Alternately, in chemical treatment, a glass slab treated containing network formers and modifiers is submerged into a molten salt bath containing ions larger than those present in the modifier. Due to a concentration gradient of the ions, mass transport must take place. As the larger cation diffuses from the molten salt into the surface, it replaces the smaller ion from the modifier. The larger ion squeezing into surface introduces compressive stress in the glass's surface. A common example is treatment of sodium oxide modified silicate glass in molten potassium chloride.

Applications and current research

Strengthening of materials is useful in many applications. A primary application of strengthened materials is for construction. In order to have stronger buildings and bridges, one must have a strong frame that can support high tensile or compressive load and resist plastic deformation. The steel frame used to make the building should be as strong as possible so that it does not bend under the entire weight of the building. Polymeric roofing materials would also need to be strong so that the roof does not cave in when there is build-up of snow on the rooftop.

Research is also currently being done to increase the strength of metallic materials through the addition of polymer materials such as bonded carbon fiber reinforced polymer to (CFRP).

Molecular dynamics simulations

The use of computation simulations to model work hardening in materials allows for the direct observation of critical elements that rule the process of strengthening materials. The basic reasoning derives from the fact that, when examining plasticity and the movement of dislocations in materials, a focus on the atomistic level is many times not accounted for and the focus rests on the contiuum description of materials. Since the practice of tracking these atomistic effects in experiments and theorizing about them in textbooks cannot provide a full understanding of these interactions, many turn to molecular dynamics simulations to develop this understanding.[7]

The simulations work by utilizing the known atomic interactions between any two atoms and the relationship F = ma, so that the dislocations moving through the material are ruled by simple mechanical actions and reactions of the atoms. The interatomic potential usually utilized to estimate these interactions is the Lennard – Jones 12:6 potential. Lennard – Jones is widely accepted because its experimental shortcomings are well-known.[7][8] These interactions are simply scaled up to millions or billions of atoms in some cases to simulate materials more accurately.

Molecular dynamic simulations display the interactions based upon the governing equations provided above for the strengthening mechanisms. They provide an effective way to see these mechanisms in action outside the painstaking realm of direct observation during experiments.

See also

- Tempering (metallurgy)

- Strength of materials

- Work hardening

- Solid solution strengthening

- Precipitation strengthening

- Grain boundary strengthening

References

- ↑ Davidge, R.W., Mechanical Behavior of Ceramics, Cambridge Solid State Science Series, (1979)

- ↑ Lawn, B.R., Fracture of Brittle Solids, Cambridge Solid State Science Series, 2nd Edn. (1993)

- ↑ Green, D., An Introduction to the Mechanical Properties of Ceramics, Cambridge Solid State Science Series, Eds. Clarke, D.R., Suresh, S., Ward, I.M. (1998)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Callister, William Jr, Materials Science and Engineering, An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons, NY, NY 1985

- ↑ D. Kuhlmann-Wilsdorf, "Theory of Plastic Deformation," Materials Science and Engineering A, vol 113, pp 1-42, July 1989

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Meyers, Chawla. Mechanical Behavior of Materials. Cambridge University Press. pg 420-425. 1999

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Buehler, Markus J. the dynamical complexity of work - hardening: a large-scale molecular dynamics simulation. Acta Mech Sinica. pg 103-111. 2005

- ↑ Abraham, F. "Simulating materials failure by using up to one billion atoms and the world's fastest computer: Work-hardening." Proc Natl Acad Sci. pg 5783–5787. 2002