Streatham

| Streatham | |

Streatham High Road, looking north from the junction of Streatham High Road and Mitcham Lane |

|

Streatham |

|

| OS grid reference | TQ305715 |

|---|---|

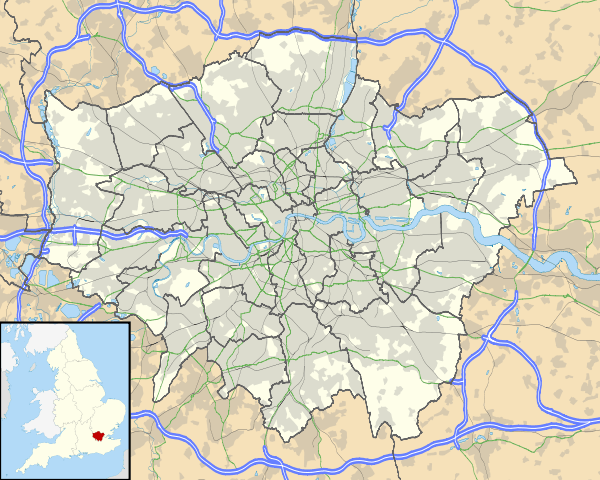

| London borough | Lambeth |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | London |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | SW16 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| EU Parliament | London |

| UK Parliament | Streatham |

| London Assembly | Lambeth and Southwark |

Coordinates: 51°25′40″N 0°07′25″W / 51.4279°N 0.1235°W

Streatham (/ˈstrɛt.əm/) is a district in south London, England, mostly in the London Borough of Lambeth. It is centred 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Charing Cross. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.[1]

History

Streatham means "the hamlet on the street". The street in question, the London to Brighton Way, was the Roman road from the capital Londinium to the south coast near Portslade, today within Brighton and Hove. It is likely that the destination was a Roman port now lost to coastal erosion, which has been tentatively identified with 'Novus Portus' mentioned in Ptolemy's Geographia.[2] The road is as with many confusingly referred to as Stane Street (Stone Street) in some sources and diverges from the main London-Chichester road at Kennington.

After the departure of the Romans, the main road through Streatham remained an important trackway. From the 17th century it was adopted as the main coach road to Croydon and East Grinstead, and then on to Newhaven and Lewes. In 1780 it then became the route of the turnpike road from London to Brighton, and subsequently became the basis for the modern A23. This road (and its traffic) have shaped Streatham's development.

Streatham's first parish church, St Leonard's was founded in Saxon times but an early Tudor tower remains is the only structure pre-1831 which the church has as it was rebuilt.[3] The mediaeval parish covered a wider area by including Balham and Tooting Bec. Streatham Cemetery on Garratt Lane on the borders of Wimbledon is one of the few remaining indications of how far west Streatham once extended.[3]

Streatham appears in Domesday Book of 1086 as Estreham. It was held by Bec-Hellouin Abbey (in Normandy) from Richard de Tonbrige. Its domesday assets were: 2 hides, 1 virgate and 6½ ploughlands of cultivated land and 4 acres (1.6 ha) of meadow and herbage (mixed grass and bracken). Annually it was assessed to render £4 5s 0d to its overlords.[4]

Streatham Village and Streatham Wells

The village remained largely unchanged until the 18th century, when the village's natural springs, known as Streatham Wells, were first celebrated for their health-giving properties. The reputation of the spa, and improved turnpike roads, attracted wealthy City of London merchants and others to build their country residences in Streatham.

In spite of London's expansion around the village, a limited number of developments took place in the village in the second half of the Nineteenth Century, most notably on Wellfield Road and Sunnyhill Road. These roads are today considered an important part of what remains of the historic Streatham Village as they found little or no influence from the growth of metropolitan London.

Wellfield Road, which had previously been known as Leigham Lane, was renamed to reflect its role as the main route from the village centre to one of the well locations. Another mineral well was located on the south side of Streatham Common, in an area that now forms part of The Rookery.[5]

Streatham Park or Streatham Place

In the 1730s, Streatham Park, a Georgian country mansion, was built by the brewer Ralph Thrale on land he bought from the Lord of the Manor - the fourth Duke of Bedford. Streatham Park later passed to Ralph's son Henry Thrale, who with his wife Hester Thrale entertained many of the leading literary and artistic characters of the day, most notably the lexicographer Samuel Johnson. The dining room contained 12 portraits of Henry's guests painted by his friend Joshua Reynolds. These pictures were wittily labelled by Fanny Burney as the Streatham Worthies.[6]

Streatham Park was later leased to Prime Minister Lord Shelburne, and was the venue for early negotiations with France that lead to the Peace Treaty of 1783. Streatham Park was demolished in 1863.

Park Hill

One large house that survives is Park Hill, on the north side of Streatham Common, rebuilt in the early 19th century for the Leaf family. It was latterly the home of Sir Henry Tate, sugar refiner, benefactor of local libraries across south London, including Streatham Library, and founder of the Tate Gallery at Millbank.

Urbanisation

Development accelerated after the opening of Streatham Hill railway station on the West End of London and Crystal Palace Railway in 1856. The other two railway stations followed within fifteen years. Some estates, such as Telford Park to the west of Streatham Hill, were spaciously planned with facilities like tennis clubs.[7] Despite the local connections to the Dukes of Bedford, there is no link to the contemporary Bedford Park in west London. Another generously sized development was Roupell Park, the area near Christchurch Road promoted by the Roupell family. Other streets adopted more conventional suburban layouts. Three more parish churches were built to serve the growing area, including Immanuel and St Andrew's (1854), St Peter's (1870) and St Margaret the Queen's (1889). There is now a mixture of buildings from all architectural eras of the past 200 years.

The inter-war period

After the First World War Streatham developed as a location for entertainment, with Streatham Hill Theatre (now a bingo hall), three cinemas, the Locarno ballroom (latterly Caesar's nightclub, which closed in 2010) and Streatham Ice Rink all adding to its reputation as "the West End of South London". With the advent of electric tram services it also grew as a shopping centre serving a wide area to the south. In the 1930s large numbers of blocks of flats were constructed along High Road. These speculative developments were not initially successful. They were only filled when émigré communities began to arrive in London after leaving countries under the domination of Hitler's Germany. In 1932 the parish church of the Holy Redeemer was built in Streatham Vale to commemorate the work of William Wilberforce.[8]

Retail decline and recovery

In the 1950s Streatham had the longest and busiest shopping street in south London. Streatham became the site of the UK's first supermarket, when Express Dairies Premier Supermarkets opened its first 2,500 square feet (230 m2) store in 1951;[10] Waitrose subsequently opened its first supermarket in Streatham in 1955, but it closed down in 1963.[11]

However, a combination of factors led to a gradual decline through the 1970s and a more rapid decline in the 1980s. These included long term population movements out to Croydon, Kingston and Sutton; the growth of heavy traffic on the A23 (main road from central London to Gatwick Airport and Brighton); and a lack of redevelopment sites in the town centre. This culminated in 1990 when the closure of Pratts, which had grown from a Victorian draper's shop to a department store operated since the 1940s by the John Lewis Partnership, coincided with the opening of a large Sainsbury's supermarket 1 km south of the town centre, replacing an existing, smaller Sainbury's store opposite Streatham Hill railway station.

Several recent additions, such as Argos, Lidl and Peacocks, are located in new retail spaces on the site of Pratt's but, in common with other high streets, retail recovery has been slow, and a substantial proportion of vacant space has been taken by a growing number of restaurants, bars and coffee shops.

In August 2011, Streatham was selected as one of the areas to benefit from Round 1 of the Mayor of London's Outer London Fund, gaining £300,000. Later, Streatham was awarded a further £1.6 million, matched by another £1 million by Lambeth.[12] The money from this fund has and is being spent on improving streets and public spaces in Streatham. This includes the smartening up of shop fronts through painting and cleaning, replacing shutters and signage as well as helping to reveal facilities behind the high street such as The Stables Community Centre.[13] Streatham Library has also undergone a £1.2 million refurbishment. This will provide both members of the local community and businesses with valuable work space, computer and internet facilities. When it reopens in March 2014, the Tudor Hall behind the library will provide a new performance space. The central reservation along the A23 is being removed, which involves some repaving and resurfacing, planting of new trees, and the creation of an enlarged bus and cycle lane.[14] Streatham Skyline is introducing new lighting to highlight some of Streatham's more attractive buildings and monuments with the aim of improving safety and the overall attractiveness of the area.[13] The Streatham Festival has benefited from The Outer London Fund.

Contemporary Streatham

In September 2002, Streatham High Road was voted the "Worst Street in Britain"[15] in a poll organised by the BBC Today programme and CABE. This largely reflected the dominance of through traffic along High Road.

Plans for investment and regeneration had begun before the poll, with local amenity group the Streatham Society leading a successful partnership bid for funding from central government for environmental improvements. Work started in winter 2003-04 with the refurbishment of Streatham Green and repaving and relighting of the High Road between St Leonard's Church and the Odeon Cinema. In 2005 Streatham Green won the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association 'London Spade' award for best public open space scheme in the capital.

The poll was a catalyst for Lambeth London Borough Council and Transport for London's Street Management to co-operate on a joint funding arrangement for further streetscape improvements, which benefited the section of the High Road between St Leonard's and Streatham station, and the stretch north of the Odeon as far as Woodbourne Avenue. However, further spending has currently been halted because of TfL's budgetary shortfall.

Streatham Festival was established in 2002. It has grown to a festival with over 50 events held in an array of locations, from bars to churches and parks to youth centres, attracting over 3,000 people.

After several years of delay and controversy over phasing, construction started in the autumn of 2011 on the Streatham Hub - a major redevelopment next to Streatham railway station. The project is a joint development by Lambeth Council and Tesco.

The Streatham Hub project involves the demolition of Streatham Ice Arena, Streatham Leisure Centre and the former Streatham Bus Garage, and their replacement with a new leisure centre and a Tesco store with 250 flats above it. The leisure centre will be owned by Lambeth and will have an ice rink on the upper floors with a sports hall, gym and swimming pool on the levels below. Streatham Leisure Centre had been closed since November 2009 due to health and safety concerns when part of the pool hall ceiling collapsed.[16] Streatham Ice Arena closed on 18 December 2011, having celebrated eighty years of operation in February 2011.

In November 2013, the new Streatham Ice and Leisure Centre opened to the public.[17] The leisure centre houses a 60 m x 30 m indoor ice rink with 1,000 rink-side seats,[18] a six-lane 25 m swimming pool, 13 m teaching pool, four-court sports hall and a gym with 100 stations.[19]

The jazz venue Hideaway continues Streatham's long entertainment tradition. It features live performances of jazz, funk, swing and soul music as well as stand-up comedy nights. It won the Jazz Venue/Promoter of the Year category in the 2011 Parliamentary Jazz Awards.[20]

Constituency

Gallery

-

Streatham Green and shops on the section of Streatham High Road known locally as "The Dip".

-

Tate Public Library, Streatham High Road

-

The twin spires of English Martyrs Church (RC) on the right and St Leonard's Church (CofE) on the left.

-

Commuters on Streatham railway station.

-

Streatham railway station entrance on Streatham High Road.

Education

- Bishop Thomas Grant School

- Dunraven School

- Streatham & Clapham High School

- Waldorf School of South West London

- Hitherfield Primary School

- Streatham Wells Primary School

Sport

- Streatham Redskins (ice hockey)

- Dulwich Hamlet F.C.

- South London Storm (rugby league)

- Streatham-Croydon RFC

- There is an annual kite fair on Streatham Common

Places of worship

- St Leonard's Church (Church of England) - the historic parish church

- English Martyrs' Church (Roman Catholic)

- Christ Church, Streatham Hill (Church of England)

- Holy Redeemer Church, Streatham Vale (Church of England)

- St Margaret the Queen, Cricklade Avenue, Streatham Hill (Church of England)

- St Peter's Church, Streatham (Church of England)

- St Simon and St Jude, Hillside Road, Streatham Hill (Roman Catholic)

- Streatham Baptist Church, Lewin Road

- Hambro Road Baptist Church

- Streatham Methodist Church, Riggindale Road

- New Covenant Church, Pendennis Road

- Islamic Centre, Estreham Road (Shi’a)

- Streatham Friends Meeting House, Roupell Park Estate (Religious Society of Friends (Quakers))

- Streatham Mosque, Mitcham Lane (Sunni)

- Streatham Hill Mosque, Norfolk House Road (Sunni)

- South London Synagogue, Leigham Court Road (United Synagogue)

- South London Liberal Synagogue, Prentis Road (Liberal Judaism)

Notable residents

Victoria Cross-winning soldier Geoffrey Cather was from Streatham.

The first Mayor of London and former head of the GLC Ken Livingstone spent most of his childhood in Streatham.

The only official English Heritage blue plaque in central Streatham is on the childhood home of composer Arnold Bax in Pendennis Road.

Just within the modern boundaries of Streatham Hill, although historically it was in Norwood, there is also a blue plaque on the house in Lanercost Road where Arthur Mee the writer of Arthur Mee's Children's Encyclopedia lived.

Georges Montefiore-Levi (1832-1906), a Belgian inventor, born in Streatham.

Ken Mackintosh, one of the leading dance band leaders of the 1950s and '60s, lived for many years at 26 South Side, Streatham Common. Drum and bass DJ Grooverider is from Streatham. Mark King (Level 42) lived for several years in the Spinney and Boon Gould (Level 42) lived for several years in Gleneldon Road. Another resident of Gleneldon Road was Gerry Shephard, guitarist with the Glitter Band, who lived at no. 93 until his death in May 2003. Singer Jay Aston lived in Streatham after leaving Bucks Fizz.

Siobhan Dowd, author, lived in Abbotsford Road (1960–1978). Beryl Kingston, popular novelist, lived at Strathbrook Road from 1956–1980 and taught at what was then Rosa Bassett School in Welham Road, and also at Sunnyhill Primary School. Dennis Wheatley, author, was born in Streatham, and lived for a time on Valley Road. Leila Berg, author and journalist, lived for many years at 25 South Side, Streatham Common. Several of her books feature photographs by John Walmsley taken in Streatham, which depict residents of Streatham in their daily lives.

From the world of fashion, Sir Norman Hartnell, dressmaker to the Queen, was born in Streatham. Hartnell was also friends with fellow Streatham resident and well known London socialite Renee Probert-Price (1917-2013). The Dior fashion designer John Galliano spent some of his youth in Streatham, before moving to nearby Dulwich. Naomi Campbell, model, went to Dunraven Comprehensive School and lived in nearby Norbury. TV presenter Sarah Beeny has lived in Streatham for many years,[21] as has David Harewood, the British star of Homeland.[22]

Perhaps because of its good late night transport connections to the West End, and the availability of flats as well as family houses, Streatham and nearby Brixton Hill have attracted entertainers to live in the area since the days of music hall. There is a Streatham Society plaque to the birthplace of comedian Tommy Trinder at 54 Wellfield Road. Others with local connections include actors Roger Moore, Simon Callow, Peter Davison, Nicholas Clay, Neil Pearson, Catherine Russell and June Whitfield, saucy seaside postcard artist Donald McGill and comedians Eddie Izzard, Jeremy Hardy and Paul Merton. Actor Hywel Bennett lived in Streatham and attended Sunnyhill Primary School, and comedian and broadcaster Roy Hudd lived for a time on Hoadly Road.

Aleister Crowley, spent his teenage years during the 1880s in Streatham at a house opposite the present ice rink. Cynthia Payne made headlines in the 1970s and '80s with her brothel in Ambleside Avenue. Afghan warlord Zardad Khan lived in Gleneagle Road before his arrest in 2003.

Arthur Anderson, co-founder of P&O and Liberal Radical MP, lived in Streatham.

Victorian artist and illustrator Holland Tringham lived in Streatham, and reproductions of his work depicting local scenes can be seen at the pub in Streatham High Road that bears his name.

Nearest places

- Balham

- Brixton

- Clapham Park

- Crystal Palace

- Furzedown

- Mitcham

- Norbury

- Pollards Hill

- Thornton Heath

- Tooting

- Upper Norwood

- West Norwood

- Wimbledon

Nearest railway stations

- Norbury railway station

- Streatham Common railway station

- Streatham Hill railway station

- Streatham railway station

References

- ↑ Mayor of London (February 2008). "London Plan (Consolidated with Alterations since 2004)" (PDF). Greater London Authority.

- ↑ NOVVS PORTVS? Romano-British Settlement

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 H.E. Malden (editor) (1912). "Parishes: Streatham". A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 4. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ Surrey Domesday Book

- ↑ http://www.ideal-homes.org.uk/case-studies/streatham/5

- ↑ Streatham Park - description on Thrale.com - Thrale family history site

- ↑ Telford Park Estate history

- ↑ http://www.holyredeemerstreatham.org.uk/about-us/history

- ↑ http://landmark.lambeth.gov.uk/display_page.asp?section=landmark&id=3416

- ↑ Helen Gregory (2001-11-03). "It's a super anniversary: it's 50 years since the first full size self-service supermarket was unveiled in the UK". The Grocer. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ http://www.waitrosememorystore.org.uk/category_id__466.aspx

- ↑ Town Centres to receive cash boost - Streatham Guardian 3 August 2011

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 http://www.london.gov.uk/priorities/regeneration/high-streets/projects/streatham

- ↑ http://streathamnews.blogspot.co.uk/2013/11/work-scheduled-to-begin-tomorrow-to.html

- ↑ "Britons name 'best and worst streets'". BBC. 2002-09-20.

- ↑ Lambeth Council closes Streatham swimming pool - Streatham Guardian 18 November 2009

- ↑ Streatham ice rink and sports centre opens

- ↑ http://www.lambeth.gov.uk/places/streatham-ice-and-leisure-centre

- ↑ http://streathamwellslabour.org.uk/2013/11/streatham-ice-and-leisure-centre-is-now-open/

- ↑ "Winners announced at the Parliamentary Jazz Awards". News and events. PPL. 18 May 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ Cavendish, Lucy (2009-01-11). "Interview: Sarah Beeny, TV property expert". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ↑ Harewood, David (2012-04-29). "Streatham's no s***hole, it's a vibrant place I'm proud to call my home". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 2013-05-02.

Further reading

- Daniel Lysons (1792), "Streatham", Environs of London, 1: County of Surrey, London: T. Cadell

- James Thorne (1876), "Streatham", Handbook to the Environs of London, London: John Murray

External links

- The Streatham Society - local amenity society with active local history group

- Streatham - A 19th Century Dormitory Suburb - history of Suburban Streatham by Graham Gower

- Streatham Art - Artists Studios Open to the Public

- Streatham in the Domesday Book

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Section 4: | Capital Ring Walking Route | Section 5: |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Palace | Streatham | Wimbledon Park |