Streaming algorithm

In computer science, streaming algorithms are algorithms for processing data streams in which the input is presented as a sequence of items and can be examined in only a few passes (typically just one). These algorithms have limited memory available to them (much less than the input size) and also limited processing time per item.

These constraints may mean that an algorithm produces an approximate answer based on a summary or "sketch" of the data stream in memory.

History

Though streaming algorithms had already been studied by Munro and Paterson[1] as well as Flajolet and Martin,[2] the field of streaming algorithms was first formalized and popularized in a paper by Noga Alon, Yossi Matias, and Mario Szegedy.[3] For this paper, the authors later won the Gödel Prize in 2005 "for their foundational contribution to streaming algorithms." There has since been a large body of work centered around data streaming algorithms that spans a diverse spectrum of computer science fields such as theory, databases, networking, and natural language processing.

Semi-streaming algorithms were introduced in 2005 as an extension of streaming algorithms that allows for a constant or logarithmic number of passes over the dataset .

Models

In the data stream model, some or all of the input data that are to be operated on are not available for random access from disk or memory, but rather arrive as one or more continuous data streams.

Streams can be denoted as an ordered sequence of points (or "updates") that must be accessed in order and can be read only once or a small number of times.

Much of the streaming literature is concerned with computing statistics on

frequency distributions that are too large to be stored. For this class of

problems, there is a vector  (initialized to the zero vector

(initialized to the zero vector  ) that has updates

presented to it in a stream. The goal of these algorithms is to compute

functions of

) that has updates

presented to it in a stream. The goal of these algorithms is to compute

functions of  using considerably less space than it

would take to represent

using considerably less space than it

would take to represent  precisely. There are two

common models for updating such streams, called the "cash register" and

"turnstile" models.[4]

precisely. There are two

common models for updating such streams, called the "cash register" and

"turnstile" models.[4]

In the cash register model each update is of the form  , so that

, so that  is incremented by some positive

integer

is incremented by some positive

integer  . A notable special case is when

. A notable special case is when  (only unit insertions are permitted).

(only unit insertions are permitted).

In the turnstile model each update is of the form  , so that

, so that  is incremented by some (possibly negative) integer

is incremented by some (possibly negative) integer  . In the "strict turnstile" model, no

. In the "strict turnstile" model, no

at any time may be less than zero.

at any time may be less than zero.

Several papers also consider the "sliding window" model. In this model, the function of interest is computing over a fixed-size window in the stream. As the stream progresses, items from the end of the window are removed from consideration while new items from the stream take their place.

Besides the above frequency-based problems, some other types of problems have also been studied. Many graph problems are solved in the setting where the adjacency matrix or the adjacency list of the graph is streamed in some unknown order. There are also some problems that are very dependent on the order of the stream (i.e., asymmetric functions), such as counting the number of inversions in a stream and finding the longest increasing subsequence.

Evaluation

The performance of an algorithm that operates on data streams is measured by three basic factors:

- The number of passes the algorithm must make over the stream.

- The available memory.

- The running time of the algorithm.

These algorithms have many similarities with online algorithms since they both require decisions to be made before all data are available, but they are not identical. Data stream algorithms only have limited memory available but they may be able to defer action until a group of points arrive, while online algorithms are required to take action as soon as each point arrives.

If the algorithm is an approximation algorithm then the accuracy of the answer is another key factor. The accuracy is often stated as an  approximation meaning that the algorithm achieves an error of less than

approximation meaning that the algorithm achieves an error of less than  with probability

with probability  .

.

Applications

Streaming algorithms have several applications in networking such as monitoring network links for elephant flows, counting the number of distinct flows, estimating the distribution of flow sizes, and so on.[5] They also have applications in databases, such as estimating the size of a join .

Some streaming problems

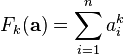

Frequency moments

The  th frequency moment of a set of frequencies

th frequency moment of a set of frequencies

is defined as

is defined as  .

.

The first moment  is simply the sum of the frequencies

(i.e., the total count). The second moment

is simply the sum of the frequencies

(i.e., the total count). The second moment  is useful for

computing statistical properties of the data, such as the Gini coefficient

of variation.

is useful for

computing statistical properties of the data, such as the Gini coefficient

of variation.  is defined as the frequency of the

most frequent item(s).

is defined as the frequency of the

most frequent item(s).

The seminal paper of Alon, Matias, and Szegedy dealt with the problem of estimating the frequency moments.

Heavy hitters

Find the most frequent (popular) elements in a data stream. Some notable algorithms are:

- Karp-Papadimitriou-Shenker algorithm

- Count-Min sketch

- Sticky sampling

- Lossy counting

- Sample and Hold

- Multi-stage Bloom filters

- Count-sketch

- Sketch-guided sampling

Event detection

Detecting events in data streams is often done using an heavy hitters algorithm as listed above: the most frequent items and their frequency are determined using one of these algorithms, then the largest increase over the previous time point is reported as trend. This approach can be refined by using exponentially weighted moving averages and variance for normalization.[6]

Counting distinct elements

Counting the number of distinct elements in a stream (sometimes called the

moment) is another problem that has been well studied.

The first algorithm for it was proposed by Flajolet and Martin. In 2010, D. Kane, J. Nelson and D. Woodruff found an asymptotically optimal algorithm for this problem.[7] It uses O(ε^2 + log d) space, with O(1) worst-case update and reporting times, as well as universal hash functions and a r-wise independent hash family where r = Ω(log(1/ε)/ log log(1/ε)) ..

moment) is another problem that has been well studied.

The first algorithm for it was proposed by Flajolet and Martin. In 2010, D. Kane, J. Nelson and D. Woodruff found an asymptotically optimal algorithm for this problem.[7] It uses O(ε^2 + log d) space, with O(1) worst-case update and reporting times, as well as universal hash functions and a r-wise independent hash family where r = Ω(log(1/ε)/ log log(1/ε)) ..

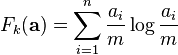

Entropy

The (empirical) entropy of a set of frequencies  is

defined as

is

defined as  , where

, where  .

.

Estimation of this quantity in a stream has been done by:

- McGregor et al.

- Do Ba et al.

- Lall et al.

- Chakrabarti et al.

Online learning

Learn a model (e.g. a classifier) by a single pass over a training set.

Lower bounds

Lower bounds have been computed for many of the data streaming problems that have been studied. By far, the most common technique for computing these lower bounds has been using communication complexity.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Munro & Paterson (1980)

- ↑ Flajolet & Martin (1985)

- ↑ Alon, Matias & Szegedy (1996)

- ↑ Gilbert et al. (2001)

- ↑ Xu (2007)

- ↑ Schubert, E.; Weiler, M.; Kriegel, H. P. (2014). SigniTrend: scalable detection of emerging topics in textual streams by hashed significance thresholds. Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining - KDD '14. pp. 871–880. doi:10.1145/2623330.2623740. ISBN 9781450329569.

- ↑ Kane, Nelson & Woodruff (2010)

References

- Alon, Noga; Matias, Yossi; Szegedy, Mario (1999), "The space complexity of approximating the frequency moments", Journal of Computer and System Sciences 58 (1): 137–147, doi:10.1006/jcss.1997.1545, ISSN 0022-0000. First published as Alon, Noga; Matias, Yossi; Szegedy, Mario (1996), "The space complexity of approximating the frequency moments", Proceedings of the 28th ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC 1996), pp. 20–29, doi:10.1145/237814.237823, ISBN 0-89791-785-5.

- Babcock, Brian; Babu, Shivnath; Datar, Mayur; Motwani, Rajeev; Widom, Jennifer (2002), "Models and issues in data stream systems", Proceedings of the 21st ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGART Symposium on Principles of Database Systems (PODS 2002), pp. 1–16, doi:10.1145/543613.543615.

- Gilbert, A. C.; Kotidis, Y.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Strauss, M. J. (2001), "Surfing Wavelets on Streams: One-Pass Summaries for Approximate Aggregate Queries", Proceedings of the International Conference on Very Large Data Bases: 79–88.

- Kane, Daniel M.; Nelson, Jelani; Woodruff, David P. (2010), An optimal algorithm for the distinct elements problem, PODS '10, New York, NY, USA: ACM, pp. 41–52, doi:10.1145/1807085.1807094, ISBN 978-1-4503-0033-9

.

- Karp, R. M.; Papadimitriou, C. H.; Shenker, S. (2003), "A simple algorithm for finding frequent elements in streams and bags", ACM Transactions on Database Systems 28 (1): 51–55, doi:10.1145/762471.762473.

- Lall, Ashwin; Sekar, Vyas; Ogihara, Mitsunori; Xu, Jun; Zhang, Hui (2006), "Data streaming algorithms for estimating entropy of network traffic", Proceedings of the Joint International Conference on Measurement and Modeling of Computer Systems (ACM SIGMETRICS 2006), doi:10.1145/1140277.1140295.

- Xu, Jun (Jim) (2007), A Tutorial on Network Data Streaming.

External links

- Princeton Lecture Notes

- Streaming Algorithms for Geometric Problems, by Piotr Indyk, MIT

- Dagstuhl Workshop on Sublinear Algorithms

- IIT Kanpur Workshop on Data Streaming

- List of open problems in streaming (compiled by Andrew McGregor) from discussion at the IITK Workshop on Algorithms for Data Streams, 2006.

- StreamIt - programming language and compilation infrastructure by MIT CSAIL

- IBM Spade - Stream Processing Application Declarative Engine

- IBM InfoSphere Streams

- Tutorials and surveys

- Data Stream Algorithms and Applications by S. Muthu Muthukrishnan

- Stanford STREAM project survey

- Network Applications of Bloom filters, by Broder and Mitzenmacher

- Xu's SIGMETRICS 2007 tutorial

- Lecture notes from Data Streams course at Barbados in 2009, by Andrew McGregor and S. Muthu Muthukrishnan

- Courses