Strategy and tactics of guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which a small group of combatants such as armed civilians or irregulars use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics, and mobility to fight a larger and less-mobile traditional military.

Guerrilla warfare as a continuum

An insurgency, or what Mao Zedong referred to as a war of revolutionary nature, guerrilla warfare can be conceived of as part of a continuum.[1] On the low end are small-scale raids, ambushes and attacks. In ancient times these actions were often associated with smaller tribal policies fighting a larger empire, as in the struggle of Rome against the Spanish tribes for over a century. In the modern era they continue with the operations of insurgent, revolutionary and terrorist groups. The upper end is composed of a fully integrated political-military strategy, comprising both large and small units, engaging in constantly shifting mobile warfare, both on the low-end "guerrilla" scale, and that of large, mobile formations with modern arms.

The latter phase came to fullest expression in the operations of Mao Zedong in China and Vo Nguyen Giap in Vietnam. In between are a large variety of situations - from the wars waged against Israel by Palestinian irregulars in the contemporary era, to Spanish and Portuguese irregulars operating with the conventional units of British General Wellington, during the Peninsular War against Napoleon.[2]

Modern insurgencies and other types of warfare may include guerrilla warfare as part of an integrated process, complete with sophisticated doctrine, organization, specialist skills and propaganda capabilities. Guerrillas can operate as small, scattered bands of raiders, but they can also work side by side with regular forces, or combine for far ranging mobile operations in squad, platoon or battalion sizes, or even form conventional units. Based on their level of sophistication and organization, they can shift between all these modes as the situation demands. Successful guerrilla warfare is flexible, not static.

Strategic models of guerrilla warfare

The 'classic' three-phase Maoist model

In China, the Maoist Theory of People's War divides warfare into three phases. In Phase One, the guerrillas earn population's support by distributing propaganda and attacking the organs of government. In Phase Two, escalating attacks are launched against the government's military forces and vital institutions. In Phase Three, conventional warfare and fighting are used to seize cities, overthrow the government, and assume control of the country. Mao's doctrine anticipated that circumstances may require shifting between phases in either directions and that the phases may not be uniform and evenly paced throughout the countryside. Mao Zedong's seminal work, On Guerrilla Warfare,[4] has been widely distributed and applied most successfully in Vietnam, by military leader and theorist Vo Nguyen Giap, whose "Peoples War, Peoples Army"[5] closely follows the Maoist three-phase approach, but emphasizing flexibility in shifting between guerrilla warfare and a spontaneous "General Uprising" of the population in conjunction with guerrilla forces. Some authors have stressed this interchangeability of phases inherent in this model and guerrilla warfare more generally, especially as applied by the North Vietnamese guerrilla.[6]

The more fragmented contemporary pattern

The classical Maoist model requires a strong, unified guerrilla group and a clear objective. However, some contemporary guerrilla warfare may not follow this template at all, and might encompass vicious ethnic strife, religious fervor, and numerous small, 'freelance' groups operating independently with little overarching structure. These patterns do not fit easily into neat phase-driven categories, or formal three-echelon structures (Main Force regulars, Regional fighters, part-time Guerrillas) as in the People's Wars of Asia.

Some jihadist guerrilla attacks for example, may be driven by a generalized desire to restore a reputed golden age of earlier times, with little attempt to establish a specific alternative political regime in a specific place. Ethnic attacks likewise may remain at the level of bombings, assassinations, or genocidal raids as a matter of avenging some perceived slight or insult, rather than a final shift to conventional warfare as in the Maoist formulation.[7]

Environmental conditions such as increasing urbanization, and the easy access to information and media attention also complicate the contemporary scene. Guerrillas need not conform to the classic rural fighter helped by cross-border sanctuaries in a confined nation or region, (as in Vietnam) but now include vast networks of peoples bound by religion and ethnicity stretched across the globe.[8]

Tactics

Guerrilla warfare is distinguished from the small unit tactics used in screening or reconnaissance operations typical of conventional forces. It is also different from the activities of pirates or robbers. Such criminal groups may use guerrilla-like tactics, but their primary purpose is immediate material gain, and not a political objective.

Guerrilla tactics are based on intelligence, ambush, deception, sabotage, and espionage, undermining an authority through long, low-intensity confrontation. It can be quite successful against an unpopular foreign or local regime, as demonstrated by the Cuban Revolution, Afghanistan War and Vietnam War. A guerrilla army may increase the cost of maintaining an occupation or a colonial presence above what the foreign power may wish to bear. Against a local regime, the guerrilla fighters may make governance impossible with terror strikes and sabotage, and even combination of forces to depose their local enemies in conventional battle. These tactics are useful in demoralizing an enemy, while raising the morale of the guerrillas. In many cases, guerrilla tactics allow a small force to hold off a much larger and better equipped enemy for a long time, as in Russia's Second Chechen War and the Second Seminole War fought in the swamps of Florida (United States of America). Guerrilla tactics and strategy are summarized below and are discussed extensively in standard reference works such as Mao's "On Guerrilla Warfare."[4]

Types of tactical operations

Guerrilla operations typically include a variety of strong surprise attacks on transportation routes, individual groups of police or military, installations and structures, economic enterprises, and targeted civilians. Attacking in small groups, using camouflage and often captured weapons of that enemy, the guerrilla force can constantly keep pressure on its foes and diminish its numbers, while still allowing escape with relatively few casualties. The intention of such attacks is not only military but political, aiming to demoralize target populations or governments, or goading an overreaction that forces the population to take sides for or against the guerrillas. Examples range from the chopping off of limbs in various internal African rebellions, to the suicide bombings in Israel and Sri Lanka, to sophisticated manoeuvres by Viet Cong and NVA forces against military bases and formations.

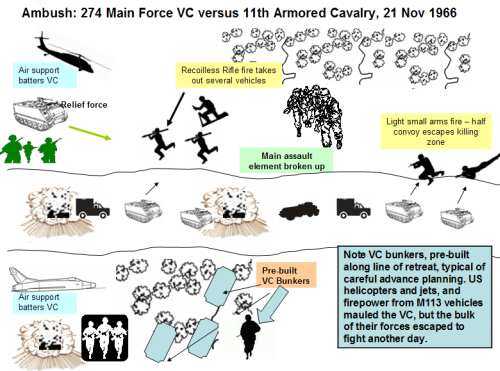

Whatever the particular tactic used, the guerrilla primarily lives to fight another day, and to expand or preserve his forces and political support, not capture or holding specific blocks of territory as a conventional force would. Above is a simplified version of a typical ambush attack by one of the most effective of post-WWII guerrilla forces, the Viet Cong (VC).

Ambushes on key transportation routes are a hallmark of guerrilla operations, causing both economic and political disruption. Careful planning is required for operations, indicated here by VC preparation of the withdrawal route. In this case the Viet Cong assault was broken up by American aircraft and firepower. However, the VC did destroy several vehicles and the bulk of the main VC force escaped. As in most of the Vietnam War, American forces would eventually leave the area, but the insurgents would regroup and return afterwards. This time dimension is also integral to guerrilla tactics.[9]

Organization

Guerrilla warfare resembles rebellion, yet it is a different concept. Guerrilla organization ranges from small, local rebel groups of a few dozen guerrillas, to thousands of fighters, deploying from cells to regiments. In most cases, the leaders have clear political aims for the warfare they wage. Typically, the organization has political and military wings, to allow the political leaders "plausible denial" for military attacks.[10] The most fully elaborated guerrilla warfare structure is by the Chinese and Vietnamese communists during the revolutionary wars of East and Southeast Asia.[11] A simplified example of this more sophisticated organizational type - used by revolutionary forces during the Vietnam War, is shown above.

Surprise and intelligence

For successful operations, surprise must be achieved by the guerrillas. If the operation has been betrayed or compromised it is usually called off immediately. Intelligence is also extremely important, and detailed knowledge of the target's dispositions, weaponry and morale is gathered before any attack. Intelligence can be harvested in several ways. Collaborators and sympathizers will usually provide a steady flow of useful information. If working clandestinely, the guerrilla operative may disguise his membership in the insurgent operation, and use deception to ferret out needed data. Employment or enrollment as a student may be undertaken near the target zone, community organizations may be infiltrated, and even romantic relationships struck up as part of intelligence gathering.[12] Public sources of information are also invaluable to the guerrilla, from the flight schedules of targeted airlines, to public announcements of visiting foreign dignitaries, to Army Field Manuals. Modern computer access via the World Wide Web makes harvesting and collation of such data relatively easy.[13] The use of on the spot reconnaissance is integral to operational planning. Operatives will "case" or analyze a location or potential target in depth- cataloguing routes of entry and exit, building structures, the location of phones and communication lines, presence of security personnel and a myriad of other factors. Finally intelligence is concerned with political factors- such as the occurrence of an election or the impact of the potential operation on civilian and enemy morale.

Relationships with the civil population

"Why does the guerrilla fighter fight? We must come to the inevitable conclusion that the guerrilla fighter is a social reformer, that he takes up arms responding to the angry protest of the people against their oppressors, and that he fights in order to change the social system that keeps all his unarmed brothers in ignominy and misery."

Relationships with civilian populations are influenced by whether the guerrillas operate among a hostile or friendly population. A friendly population is of immense importance to guerrilla fighters, providing shelter, supplies, financing, intelligence and recruits. The "base of the people" is thus the key lifeline of the guerrilla movement. In the early stages of the Vietnam War, American officials "discovered that several thousand supposedly government-controlled 'fortified hamlets' were in fact controlled by Viet Cong guerrillas, who 'often used them for supply and rest havens'."[15] Popular mass support in a confined local area or country however is not always strictly necessary. Guerrillas and revolutionary groups can still operate using the protection of a friendly regime, drawing supplies, weapons, intelligence, local security and diplomatic cover.

An apathetic or hostile population makes life difficult for guerrilleros and strenuous attempts are usually made to gain their support. These may involve not only persuasion, but a calculated policy of intimidation. Guerrilla forces may characterize a variety of operations as a liberation struggle, but this may or may not result in sufficient support from affected civilians. Other factors, including ethnic and religious hatreds, can make a simple national liberation claim untenable. Whatever the exact mix of persuasion or coercion used by guerrillas, relationships with civil populations are one of the most important factors in their success or failure.[16]

Use of terror

In some cases, the use of terrorism can be an aspect of guerrilla warfare. Terrorism is used to focus international attention on the guerrilla cause, kill opposition leaders, extort money from targets, intimidate the general population, create economic losses, and keep followers and potential defectors in line. As well, the use of terrorism can provoke the greater power to launch a disproportionate response, thus alienating a civilian population which might be sympathetic to the terrorist's cause. Such tactics may backfire and cause the civil population to withdraw its support, or to back countervailing forces against the guerrillas.[10]

Such situations occurred in Israel, where suicide bombings encouraged most Israeli opinion to take a harsh stand against Palestinian attackers, including general approval of "targeted killings" to kill enemy cells and leaders.[17] In the Philippines and Malaysia, communist terror strikes helped turn civilian opinion against the insurgents. In Peru and some other countries, civilian opinion at times backed the harsh countermeasures used by governments against revolutionary or insurgent movements.

Withdrawal

Guerrillas must plan carefully for withdrawal once an operation has been completed, or if it is going badly. The withdrawal phase is sometimes regarded as the most important part of a planned action, and to get entangled in a lengthy struggle with superior forces is usually fatal to insurgent, terrorist or revolutionary operatives. Withdrawal is usually accomplished using a variety of different routes and methods and may include quickly scouring the area for loose weapons, evidence cleanup, and disguise as peaceful civilians.[4]

Logistics

Guerrillas typically operate with a smaller logistical footprint compared to conventional formations; nevertheless, their logistical activities can be elaborately organized. A primary consideration is to avoid dependence on fixed bases and depots which are comparatively easy for conventional units to locate and destroy. Mobility and speed are the keys and wherever possible, the guerrilla must live off the land, or draw support from the civil population in which it is embedded. In this sense, "the people" become the guerrilla's supply base.[4] Financing of both terrorist and guerrilla activities ranges from direct individual contributions (voluntary or non-voluntary), and actual operation of business enterprises by insurgent operatives, to bank robberies, kidnappings and complex financial networks based on kin, ethnic and religious affiliation (such as that used by modern Jihadist/Jihad organizations).

Permanent and semi-permanent bases form part of the guerrilla logistical structure, usually located in remote areas or in cross-border sanctuaries sheltered by friendly regimes.[18] These can be quite elaborate, as in the tough VC/NVA fortified base camps and tunnel complexes encountered by US forces during the Vietnam War. Their importance can be seen by the hard fighting sometimes engaged in by communist forces to protect these sites. However, when it became clear that defence was untenable, communist units typically withdrew without sentiment.

Terrain

Guerrilla warfare is often associated with a rural setting, and this is indeed the case with the definitive operations of Mao and Giap, the mujahadeen of Afghanistan, the Ejército Guerrillero de los Pobres (EGP) of Guatemala, the Contras of Nicaragua, and the FMLN of El Salvador. Guerrillas however have successfully operated in urban settings as demonstrated in places like Argentina and Northern Ireland. In those cases, guerrillas rely on a friendly population to provide supplies and intelligence. Rural guerrillas prefer to operate in regions providing plenty of cover and concealment, especially heavily forested and mountainous areas. Urban guerrillas, rather than melting into the mountains and jungles, blend into the population and are also dependent on a support base among the people. Removing and destroying guerrillas out of both types of areas can be difficult.

Foreign support and sanctuaries

Foreign support in the form of soldiers, weapons, sanctuary, or statements of sympathy for the guerrillas is not strictly necessary, but it can greatly increase the chances of an insurgent victory.[12] Foreign diplomatic support may bring the guerrilla cause to international attention, putting pressure on local opponents to make concessions, or garnering sympathetic support and material assistance. Foreign sanctuaries can add heavily to guerrilla chances, furnishing weapons, supplies, materials and training bases. Such shelter can benefit from international law, particularly if the sponsoring government is successful in concealing its support and in claiming "plausible denial" for attacks by operatives based in its territory.

The VC and NVA made extensive use of such international sanctuaries during their conflict, and the complex of trails, way-stations and bases snaking through Laos and Cambodia, the famous Ho Chi Minh Trail, was the logistical lifeline that sustained their forces in the South. Also, the United States funded a revolution in Colombia in order to take the territory they needed to build the Panama Canal. Another case in point is the Mukti Bahini guerrilleros who fought alongside the Indian Army in the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 against Pakistan that resulted in the creation of the state of Bangladesh. In the post-Vietnam era, the Al Qaeda organization also made effective use of remote territories, such as Afghanistan under the Taliban regime, to plan and execute its operations.

Guerrilla initiative and combat intensity

Able to choose the time and place to strike, guerrilla fighters will usually possess the tactical initiative and the element of surprise. Planning for an operation may take weeks, months or even years, with a constant series of cancellations and restarts as the situation changes.[19] Careful rehearsals and "dry runs" are usually conducted to work out problems and details. Many guerrilla strikes are not undertaken unless clear numerical superiority can be achieved in the target area, a pattern typical of VC/NVA and other "Peoples War" operations. Individual suicide bomb attacks offer another pattern, typically involving only the individual bomber and his support team, but these too are spread or metered out based on prevailing capabilities and political winds.

Whatever approach is used, the guerrilla holds the initiative and can prolong his survival though varying the intensity of combat. This means that attacks are spread out over quite a range of time, from weeks to years. During the interim periods, the guerrilla can rebuild, resupply and plan. In the Vietnam War, most communist units (including mobile NVA regulars using guerrilla tactics) spent only a limited number of days a year fighting. While they might be forced into an unwanted battle by an enemy sweep, most of the time was spent in training, intelligence gathering, political and civic infiltration, propaganda indoctrination, construction of fortifications, or stocking supply caches.[11] The large numbers of such groups striking at different times however, gave the war its "around the clock" quality.

Other aspects

Foreign and native regimes

Examples of successful guerrilla warfare against a native regime include the Cuban Revolution and the Chinese Civil War, as well as the Sandinista Revolution which overthrew a military dictatorship in Nicaragua. The many coups and rebellions of Africa often reflect guerrilla warfare, with various groups having clear political objectives and using guerrilla tactics. Examples include the overthrow of regimes in Uganda, Liberia and other places. In Asia, native or local regimes have been overthrown by guerrilla warfare, most notably in Vietnam, China and Cambodia.

Foreign forces intervened in all these countries, but the power struggles were eventually resolved locally.

There are many unsuccessful examples of guerrilla warfare against local or native regimes. These include Portuguese Africa (Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau), Malaysia (then Malaya) during the Malayan Emergency, Bolivia, Argentina, and the Philippines. It was even able to use these tactics effectively against the Indian Peace Keeping Force sent by India in the mid-1980s, which were later withdrawn for varied reasons, primarily political. The Tigers are fighting to create a separate homeland for Sri Lankan Tamils, many of whom complain of marginalisation by successive governments led by the Sinhalese majority since independence from Britain in 1948.

Ethical dimensions

Civilians may be attacked or killed as punishment for alleged collaboration, or as a policy of intimidation and coercion. Such attacks are usually sanctioned by the guerrilla leadership with an eye toward the political objectives to be achieved. Attacks may be aimed to weaken civilian morale so that support for the guerrilla's opponents decreases. Civil wars may also involve deliberate attacks against civilians, with both guerrilla groups and organized armies committing atrocities. Ethnic and religious feuds may involve widespread massacres and genocide as competing factions inflict massive violence on targeted civilian population.

Guerrillas in wars against foreign powers may direct their attacks at civilians, particularly if foreign forces are too strong to be confronted directly on a long term basis. In Vietnam, bombings and terror attacks against civilians were fairly common, and were often effective in demoralizing local opinion that supported the ruling regime and its American backers. While attacking an American base might involve lengthy planning and casualties, smaller scale terror strikes in the civilian sphere were easier to execute. Such attacks also had an effect on the international scale, demoralizing American opinion, and hastening a withdrawal.

In Iraq, most of the deaths since the 2003 US invasion have not been suffered by US troops but by civilians, as warring factions plunged the country into civil war based on ethnic and religious hostilities. (See also: Civil war in Iraq (2006–07)) Arguments vary on whether such turmoil will succeed in turning American opinion against the US troop deployment. However, the use of attacks against civilians to create an atmosphere of chaos (and thus political advantage where the atmosphere causes foreign occupiers to withdraw or offer concessions), is well established in guerrilla and national liberation struggles. Claims and counterclaims of the morality of such attacks, or whether guerrillas should be classified as "terrorists" or "freedom fighters" are beyond the scope of this article. See Terrorism and Genocide for a more in-depth discussion of the moral and ethical implications of targeting civilians.

Laws of war

Guerrilleros are in danger of not being recognized as lawful combatants because they may not wear a uniform, (to mingle with the local population), or their uniform and distinctive emblems may not be recognized as such by their opponents. This occurred in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71; see Franc-Tireurs.

Article 44, sections 3 and 4 of the 1977 First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, "relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts", does recognize combatants who, because of the nature of the conflict, do not wear uniforms as long as they carry their weapons openly during military operations. This gives non-uniformed guerrilleros lawful combatant status against countries that have ratified this convention. However, the same protocol states in Article 37.1.c that "the feigning of civilian, non-combatant status" shall constitute perfidy and is prohibited by the Geneva Conventions. So is the wearing of enemy uniform, as happened in the Boer War.

Counter-guerrilla warfare

Classic guidelines

The guerrilla can be difficult to beat, but certain principles of counter-insurgency warfare are well known since the 1950s and 1960s and have been successfully applied. The widely distributed and influential work of Sir Robert Thompson, counter-insurgency expert of the Malayan Emergency, offers several such guidelines. Thompson's underlying assumption is that of a country minimally committed to the rule of law and better governance. Some governments, however, give such considerations short shrift, and their counter-insurgency operations have involved mass murder, genocide, starvation and the massive spread of terror, torture and execution. The totalitarian regimes of Hitler are classic examples, as are more modern conflicts in places like Afghanistan. In the Soviet war in Afghanistan for example, the Soviets countered the Mujahideen with a policy of wastage and depopulation, driving over one third of the Afghan population into exile (over 5 million people), and carrying out widespread destruction of villages, granaries, crops, herds and irrigation systems, including the deadly and widespread mining of fields and pastures.

Elements of Thompson's moderate approach are adapted here:[20]

- The people are the key base to be secured and defended rather than territory won or enemy bodies counted. Contrary to the focus of conventional warfare, territory gained, or casualty counts are not of overriding importance in counter-guerrilla warfare. The support of the population is the key variable. Since many insurgents rely on the population for recruits, food, shelter, financing, and other materials, the counter-insurgent force must focus its efforts on providing physical and economic security for that population and defending it against insurgent attacks and propaganda.

- There must be a clear political counter-vision that can overshadow, match or neutralize the guerrilla vision. This can range from granting political autonomy, to economic development measures in the affected region. The vision must be an integrated approach, involving political, social and economic and media influence measures. A nationalist narrative for example, might be used in one situation, an ethnic autonomy approach in another. An aggressive media campaign must also be mounted in support of the competing vision or the counter-insurgent regime will appear weak or incompetent.

- Practical action must be taken at the lower levels to match the competitive political vision. It may be tempting for the counter-insurgent side to simply declare guerrillas "terrorists" and pursue a harsh liquidation strategy. Brute force however, may not be successful in the long run. Action does not mean capitulation, but sincere steps such as removing corrupt or arbitrary officials, cleaning up fraud, building more infrastructure, collecting taxes honestly, or addressing other legitimate grievances can do much to undermine the guerrillas' appeal.

- Economy of force. The counter-insurgent regime must not overreact to guerrilla provocations, since this may indeed be what they seek to create a crisis in civilian morale. Indiscriminate use of firepower may only serve to alienate the key focus of counterinsurgency- the base of the people. Police level actions should guide the effort and take place in a clear framework of legality, even if under a State of Emergency. Civil liberties and other customs of peacetime may have to be suspended, but again, the counter-insurgent regime must exercise restraint, and cleave to orderly procedures. In the counter-insurgency context, "boots on the ground" are even more important than technological prowess and massive firepower, although anti-guerrilla forces should take full advantage of modern air, artillery and electronic warfare assets.[21]

- Big unit action may sometimes be necessary. If police action is not sufficient to stop the guerrilla fighters, military sweeps may be necessary. Such "big battalion" operations may be needed to break up significant guerrilla concentrations and split them into small groups where combined civic-police action can control them.

- Aggressive mobility. Mobility and aggressive small unit action is extremely important for the counter-insurgent regime. Heavy formations must be lightened to aggressively locate, pursue and fix insurgent units. Huddling in static strong-points simply concedes the field to the insurgents. They must be kept on the run constantly with aggressive patrols, raids, ambushes, sweeps, cordons, roadblocks, prisoner snatches, etc.

- Ground level embedding and integration. In tandem with mobility is the embedding of hardcore counter-insurgent units or troops with local security forces and civilian elements. The US Marines in Vietnam also saw some success with this method, under its CAP (Combined Action Program) where Marines were teamed as both trainers and "stiffeners" of local elements on the ground. US Special Forces in Vietnam like the Green Berets, also caused significant local problems for their opponents by their leadership and integration with mobile tribal and irregular forces.[22] The CIA's Special Activities Division created successful guerrilla forces from the Hmong tribe during the war in Vietnam in the 1960s,[23] from the Northern Alliance against the Taliban during the war in Afghanistan in 2001,[24] and from the Kurdish Peshmerga against Ansar al-Islam and the forces of Saddam Hussein during the war in Iraq in 2003.[25][26] In Iraq, the 2007 US "surge" strategy saw the embedding of regular and special forces troops among Iraqi army units. These hardcore groups were also incorporated into local neighborhood outposts in a bid to facilitate intelligence gathering, and to strengthen ground level support among the masses.[21]

- Cultural sensitivity. Counter-insurgent forces require familiarity with the local culture, mores and language or they will experience numerous difficulties. Americans experienced this in Vietnam and during the US Iraqi Freedom invasion and occupation, where shortages of Arabic speaking interpreters and translators hindered both civil and military operations.[27]

- Systematic intelligence effort. Every effort must be made to gather and organize useful intelligence. A systematic process must be set up to do so, from casual questioning of civilians to structured interrogations of prisoners. Creative measures must also be used, including the use of double agents, or even bogus "liberation" or sympathizer groups that help reveal insurgent personnel or operations.

- Methodical clear and hold. An "ink spot" clear and hold strategy must be used by the counter-insurgent regime, dividing the conflict area into sectors, and assigning priorities between them. Control must expand outward like an ink spot on paper, systematically neutralizing and eliminating the insurgents in one sector of the grid, before proceeding to the next. It may be necessary to pursue holding or defensive actions elsewhere, while priority areas are cleared and held.

- Careful deployment of mass popular forces and special units. Mass forces include village self-defence groups and citizen militias organized for community defence and can be useful in providing civic mobilization and local security. Specialist units can be used profitably, including commando squads, long range reconnaissance and "hunter-killer" patrols, defectors who can track or persuade their former colleagues like the Kit Carson units in Vietnam, and paramilitary style groups. Strict control must be kept over specialist units to prevent the emergence of violent vigilante style reprisal squads that undermine the government's program.

- The limits of foreign assistance must be clearly defined and carefully used. Such aid should be limited either by time, or as to material and technical, and personnel support, or both. While outside aid or even troops can be helpful, lack of clear limits, in terms of either a realistic plan for victory or exit strategy, may find the foreign helper "taking over" the local war, and being sucked into a lengthy commitment, thus providing the guerrillas with valuable propaganda opportunities as the toll of dead foreigners mounts. Such a scenario occurred with the US in Vietnam, with the American effort creating dependence in South Vietnam, and war-weariness and protests back home. Heavy-handed foreign interference may also fail to operate effectively within the local cultural context, setting up conditions for failure.

- Time. A key factor in guerrilla strategy is a drawn-out, protracted conflict that wears down the will of the opposing counter-insurgent forces. Democracies are especially vulnerable to the factor of time. The counter-insurgent force must allow enough time to get the job done. Impatient demands for victory centered around short-term electoral cycles play into the hands of the guerrillas, though it is equally important to recognize when a cause is lost and the guerrillas have won.

Variants

Some writers on counter-insurgency warfare emphasize the more turbulent nature of today's guerrilla warfare environment, where the clear political goals, parties and structures of such places as Vietnam, Malaysia, or El Salvador are not as prevalent. These writers point to numerous guerrilla conflicts that center around religious, ethnic or even criminal enterprise themes, and that do not lend themselves to the classic "national liberation" template.

The wide availability of the Internet has also cause changes in the tempo and mode of guerrilla operations in such areas as coordination of strikes, leveraging of financing, recruitment, and media manipulation. While the classic guidelines still apply, today's anti-guerrilla forces need to accept a more disruptive, disorderly and ambiguous mode of operation.

- "Insurgents may not be seeking to overthrow the state, may have no coherent strategy or may pursue a faith-based approach difficult to counter with traditional methods. There may be numerous competing insurgencies in one theater, meaning that the counterinsurgent must control the overall environment rather than defeat a specific enemy. The actions of individuals and the propaganda effect of a subjective “single narrative” may far outweigh practical progress, rendering counterinsurgency even more non-linear and unpredictable than before. The counterinsurgent, not the insurgent, may initiate the conflict and represent the forces of revolutionary change. The economic relationship between insurgent and population may be diametrically opposed to classical theory. And insurgent tactics, based on exploiting the propaganda effects of urban bombing, may invalidate some classical tactics and render others, like patrolling, counterproductive under some circumstances. Thus, field evidence suggests, classical theory is necessary but not sufficient for success against contemporary insurgencies..."[28]

Writings

Theories of Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, during the Chinese Civil War, summarized the People's Liberation Army's principles of Revolutionary Warfare in the following points for his troops: The enemy advances, we retreat. The enemy camps, we harass. The enemy tires, we attack. The enemy retreats, we pursue. A common slogan of the time went "Draw back your fist before you strike." This referred to the tactic of baiting the enemy, "drawing back the fist," before "striking" at the critical moment where they are overstretched and vulnerable. Mao made a distinction between Mobile Warfare (yundong zhan) and Guerrilla Warfare (youji zhan), but they were part of an integrated continuum aiming towards a final objective. Mao's seminal work, On Guerrilla Warfare,[29] has been widely distributed and applied, successfully in Vietnam, under military leader and theorist Vo Nguyen Giap. Giap's "Peoples War, Peoples Army"[5] closely follows the Maoist three-stage approach.

Writings of T. E. Lawrence

T. E. Lawrence, best known as "Lawrence of Arabia," introduced a theory of guerrilla warfare tactics in an article he wrote for the Encyclopædia Britannica published in 1938. In that article, he compared guerrilla fighters to a gas. The fighters disperse in the area of operations more or less randomly. They or their cells occupy a very small intrinsic space in that area, just as gas molecules occupy a very small intrinsic space in a container. The fighters may coalesce into groups for tactical purposes, but their general state is dispersed. Such fighters cannot be "rounded up." They cannot be contained. They are extremely difficult to "defeat" because they cannot be brought to battle in significant numbers. The cost in soldiers and material to destroy a significant number of them becomes prohibitive, in all senses, that is physically, economically, and morally. Lawrence describes a non-native occupying force as the enemy (such as the Turks).

Lawrence wrote down some of his theories while ill and unable to fight the Turks in his book The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. There, he reviews von Clausewitz and other theorists of war, and finds their writings inapplicable to his situation. The Arabs could not defeat the Turks in pitched battle since they were individualistic warriors not disciplined soldiers used to fight in large formations.

So instead Lawrence proposed if possible never meeting the enemy, thus giving their soldiers nothing to shoot at, unable to control anything except what ground their rifles could point to. Meanwhile, Lawrence and the Arabs could ride camels into and out of the desert, attacking railroad lines and isolated outposts with impunity, avoiding the heavily garrisoned positions and cities.

Writings of Che Guevara

One of the main guerrilla strategists was the Berber leader Abd el-Krim who fought both Spanish and French armies in the Rif Mountains in North Africa during the beginning of the 20th century. His guerrilla tactics are known to have inspired Ho Chi Minh, Mao Zedong, and Che Guevara.[30] Che Gueverra, an Argentinian revolutionary wrote extensively on Guerrilla Warfare, stressing the revolutionary potential of the guerrillas.

"The guerrilla band is an armed nucleus, the fighting vanguard of the people. It draws its great force from the mass of the people themselves. The guerrilla band is not to be considered inferior to the army against which it fights simply because it is inferior in fire power. Guerrilla warfare is used by the side which is supported by a majority but which possesses a much smaller number of arms for use in defense against oppression."

Writing of Abdul Haris Nasution

The fullest expression of the Indonesian army’s founding doctrines is found in Abdul Haris Nasution’s 1953 Fundamentals of Guerrilla Warfare.[32] The work is a mix of reproduced strategic directives from 1947-8, Nasution’s theories of guerrilla warfare, his reflections on the period just past (post-Japanese occupation) and the likely crises to come, and outlines of his legal frameworks for military justice and “guerrilla government”. The work contains similar principles to those espoused or practiced by other theorists and practitioners from Michael Collins in Ireland, T. E. Lawrence in the Middle East and Mao in China in the early Twentieth Century, to contemporary insurgents in Afghanistan and Iraq. Nasution willingly shows his influences, frequently referring to some guerrilla activities as "Wingate" actions, quoting Lawrence and drawing lessons from the recent and further past to develop and illustrate his well-thought out arguments. Where the work substantially differs from other theorist/practitioners is that General Nasution was one of the few men to have led both a guerrilla and a counter-guerrilla war. This dual perspective on the realities of ‘people’s war’ leaves the work refreshingly free of the dogmatic hyperbole and ideological contortions of similar revolutionary works from the period and manages to be both brutally direct in the methods it espouses and jarringly honest about the terrible price revolutionary guerrilla war exacts on everyone involved or affected, the civilian population most of all.[33]

Texts and treatises

Guerrilla tactics were summarized into the Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla[34] in 1969 by Carlos Marighella. This text was banned in several countries including the United States. This is probably the most comprehensive and informative book on guerrilla strategy ever published, and is available free online. Texts by Che Guevara[35] and Mao Zedong[29] on guerrilla warfare are also available.

World War II American and British writings

John Keats wrote about an American guerrilla leader in World War II: Colonel Wendell Fertig, who in 1942 organized a large guerrilla force which harassed the Japanese occupation forces on the Philippine Island of Mindanao all the way up to the liberation of the Philippines in 1945. His abilities were later utilized by the United States Army, when Fertig helped found the United States Army Special Warfare School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Others included Col. Aaron Bank, Col. Russell Volckmann, and Col. William R. Peers.[36] Volckmann commanded a guerrilla force which operated out of the Cordillera of Northern Luzon in the Philippines from the beginning of World War II to its conclusion. He remained in radio contact with US Forces,[37] prior to the invasion of Lingayen Gulf. Peers, who later became a general, commanded OSS Detachment 101 in Burma and authored a book on its operations following the war. Because the 101 was never larger than a few hundred Americans, it relied on support from various Burmese tribal groups. In particular, the vigorously anti-Japanese Kachin people were vital to the unit’s success.[36][38]

Brigadier C. Aubrey Dixon, OBE, chief small arms ammunition designer for the British during World War II and a member of the tribunal responsible for the trial of Field Marshal von Manstein, wrote Communist Guerrilla Warfare with Otto Heilbrunn.[39]

See also

- Guerrilla warfare

- History of guerrilla warfare

- NLF and PAVN strategy, organization and structure

- NLF and PAVN logistics and equipment

- Viet Cong and PAVN battle tactics

Notes

- ↑ On Guerrilla Warfare, by Mao Zedong, 1937, See the text of Mao's work online at www.marxists.org

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Warfare Conduct Of, Guerrilla Warfare," 1984 ed, p. 584)

- ↑ Vo Nguyen Giap, Big Victory, Great Task, (Pall Mall Press, London (1968)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Mao, op. cit.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Peoples War, Peoples Army, Vo Nguyen Giap

- ↑ Dan Jakopovich, Time Factor in Insurrections, Strategic Analysis, Vol. 32, No. 3, May 2008.

- ↑ Counterinsurgency Redux - David Kilcullen, 2006, , retrieved June 1, 2007

- ↑ FRANK G. HOFFMAN, "Neo-Classical counterinsurgency?", United States Army War College, Parameters Journal: Summer 2007, pp. 71-87.

- ↑ Cash, John A.; Albright, John; Sandstrum, Allan W. (1985) [1970]. "Chapter 2: CONVOY AMBUSH ON HIGHWAY 1, 21 NOVEMBER 1966". Seven Firefights in Vietnam. Vietnam Studies. WASHINGTON, D. C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-4.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Insurgency & Terrorism: Inside Modern Revolutionary Warfare", Bard E. O'Neill

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Inside the VC and the NVA, Michael Lee Lanning and Dan Cragg

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lanning/Cragg, op. cit.

- ↑ Terrorist use of web spreads

- ↑ Guerrilla Warfare, by Ernesto Guevara & Thomas M. Davies, Rowman & Littlefield, 1997, ISBN 0-8420-2678-9, pg 52

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, 14ed, "Guerrilla Warfare" p. 460-464

- ↑ "Defeating Communist Insurgency: The Lessons of Malaya and Vietnam", Robert Thompson

- ↑ Steven R. David (September 2002). "Fatal Choices: Israel's Policy of Targeted Killing" (PDF). THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES; BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY. Retrieved on 2006-08-01.

- ↑ Mao, op. cit., Lanning/Cragg, op. cit.

- ↑ Lanning/Cragg, op. cit

- ↑ Robert Thompson (1966). Defeating Communist Insurgency: The Lessons of Malaya and Vietnam, Chatto & Windus, ISBN 0-7011-1133-X

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Learning from Iraq: Counterinsurgency in American Strategy - Steven Metz. US Army Strategic Studies Institute monograph, December 2006, http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=752, retrieved June 1, 2007

- ↑ Michael Lee Lanning and Daniel Craig, Inside the VC and NVA, and Inside the LRRP's

- ↑ Shooting at the Moon: The Story of America's Clandestine War in Laos, Steerforth Press, 1996 ISBN 978-1-883642-36-5

- ↑ Bush at War, Bob Woodward, Simon & Schuster, 2002

- ↑ Operation Hotel California: The Clandestine War inside Iraq, Mike Tucker, Charles Faddis, 2008, The Lyons Press ISBN 978-1-59921-366-8

- ↑ Plan of Attack, Bob Woodward, Simon and Schuster, 2004 ISBN 978-0-7432-5547-9

- ↑ Learning from Iraq, op. cit.

- ↑ PDF (146 KiB) Counter-insurgency Redux", David Kilcullen

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 On Guerrilla Warfare, by Mao Tse-tung, 1937

- ↑ Castro, Fidel; Ignacio Ramonet; Andrew Hurley. Fidel Castro: My Life : a Spoken Autobiography (2008 ed.). Scribner. p. 680. ISBN 1-4165-5328-2.

- ↑ "Che Guevara: Revolutionary & Icon", by Trisha Ziff, Abrams Image, 2006, pg 73

- ↑ Abdul Haris Nasution,Fundamentals of Guerrilla Warfare, Informations Service of the Indonesian Armed Forces, Jakarta, 1953.

- ↑ http://smallwarsjournal.com/mag/docs-temp/59-mcelhatton.pdf Guerrilla Warfare and the Indonesian Strategic Psyche, Small Wars Journal article by Emmet McElhatton

- ↑ "Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla". Archived from the original on November 25, 2005. Retrieved December 25, 2007.

- ↑ Guerrilla Warfare, Ernesto "Che" Guevara | http://www.freepeoplesmovement.org/fpm/page.php?149

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Peers, William R. and Dean Brelis. Behind the Burma Road: The Story of America’s Most Successful Guerrilla Force. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1963.

- ↑ Russell W. Volckmann (1954), We Remained: Three Years Behind the Enemy Lines in the Philippines page 157. Online text here

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency. Behind Japanese Lines in Burma: The Stuff of Intelligence Legend (2001). Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ↑ Dixon, Brigadier C. Aubrey and Heilbrunn, Otto, Communist Guerrilla Warfare (Frederick A. Praeger, New York: 1954)