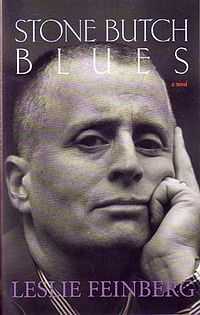

Stone Butch Blues

|

Front cover of 2004 Alyson Books paperback edition | |

| Author | Leslie Feinberg |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Firebrand Books |

Publication date | March 1993 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover and paperback) |

| ISBN | 1-56341-030-3 |

| OCLC | 27336208 |

| 813/.54 20 | |

| LC Class | PS3556.E427 S7 1993 |

Stone Butch Blues is a novel written by transgender activist Leslie Feinberg. The novel won the 1994 Stonewall Book Award. It tells the story of a butch named Jess Goldberg, and the trials and tribulations she faces growing up in the United States before the Stonewall riots. Published in 1993, the novel became an underground hit before surfacing into mainstream literature. It is generally regarded as a groundbreaking work on the subject of gender, and it is one of the best-known pieces of LGBT literature. The novel is a prominent portrait of butch and femme–culture in the late 1960s, as well as a coming-of-age story of the character Jess: a Jewish, working-class butch who runs from home as a teenager and becomes a part of gay subculture.[1]

Plot summary

Jess Goldberg, a stone butch lesbian, writes a letter to her long-lost lover, Theresa. Times have changed since Jess made her first forays into gay bars in the early 1960s—only no one used the word "gay" back then. Back then, the bars were frequented by butches, femmes (lesbians acting in traditionally feminine ways) and drag queens (gay men dressed up as women). Now, in the late 1980s, the violence is rarer, but the enemies come from their own ranks—lesbians teemed in modern feminism, who see tired sexual stereotypes in the idea of butches and femmes.

The bars are home to gays, but unfortunately they are not fortresses. Police raids are common, sudden, and crushing. Like other fraternities of masculine men, police officers take special delight in terrorizing gays. Jess also remembers the care from Theresa after such brutality.

Jess Goldberg grows up in Buffalo, New York, as a Jewish girl at a time when open anti-Semitism is pervasive. Jess is plagued by gender identity issues. One day, when her parents are out of the house, Jess tries on her father's suit and tie. Her parents come in before she expects them home, and they see Jess in male clothing. Jess is committed to the mental ward. Jess learns one important lesson: she cannot trust anyone, not even—especially—her own parents. The world is not just unhappy with her; it will destroy her if she is not vigilant.

Jess is hired part-time in a print shop. Here, she can wear jeans and a T-shirt without facing the microscopic judgment she gets at high school. But, for the first time, Jess hears someone call her a "butch." A coworker, Gloria, talks of her brother, who dresses like a woman and goes to a bar called Tifka's in Niagara Falls where people like him gather—men and women wearing each other's clothing.

It takes Jess a year to gather up the courage to go to Tifka's and she finds it to be a bar like any other, but she spots a woman who looks a bit like a man. In the back room, Jess finds what she has been hoping for—masculine women, dressed in men's suits, dancing with other women wearing high heels. When Butch Al comes into the bar. Jess freezes; here is a real butch, the butch Jess wants to grow up to be.

Jess goes to Tifka's every weekend of the summer and spends most of her time with Butch Al and Jacqueline, her femme. Butch Al becomes a mentor to Jess, teaching Jess what she needs to know to survive as a butch. One night Jess is caught in a police raid at Tifka's. The police pick out arrestees for individual beatings and rapes. Jess does what she can to comfort her friends. When Jacqueline posts bail, Al doesn't talk. Jess asks Jacqueline if she (Jess) is strong enough yet. Jacqueline replies that no one—not even Al—is strong enough. Jacqueline wishes that the femmes could do more to protect butches' hearts.

After that raid, Butch Al and Jacqueline disappear from Tifka's. Summer ends, and it's time for Jess to go back to school. When Jess goes back to Niagara Falls during the Christmas break, she learns of the deaths of Yvette and Mona—Yvette is murdered; Mona commits suicide. Jacqueline has become a junkie. No one has seen Butch Al.

After her experiences at Tifka's, life as a "normal" high school girl, living at home with her parents, becomes less and less tolerable to Jess. She spends most of her time after school at her friend Barbara's home. Jess meets Barbara in the girls' room for a smoke when Mrs. Antionette, one of the teachers, busts the girls' room. Jess escapes through the door and runs to the football field, where she is trapped and gang raped by the football players who also verbally assault her with anti-Semitic and anti-lesbian taunts.

Jess decides to quit high school, packs her suits and ties in two pillowcases and writes a farewell letter to her parents. On her first night on her own, Jess tries to sleep in the bus station, but the cops harass her so she goes to a bar called Abba's which is like Tifka's but the bartender won't serve Jess without ID. Jess finds a place to stay, thanks to a butch named Toni and her girlfriend Betty. Jess is grateful for this vital assistance, but wishes she were staying with Butch Al and Jacqueline. Jess has been absorbed into working-class, gay life in Buffalo. She is now a regular at Abba's, where the butches, femmes, and drag queens recognize her on sight. She has a job and that important butch accessory—a powerful Norton motorcycle.

One night while leaving a club, Ed and Jess are accosted and frisked by two police officers. The cops lift up Ed's shirt and pull her binder down, exposing her breasts. Jess is outraged at this violation and she and Ed go after the cops with gusto and end up bloodied in the alley. They have two matching gashes over their right eyebrows, which makes them the hit at the bar when they're able to come back. But this is the first severe beating Jess has received from the police, and it makes her realize just how vulnerable she really is.

A short time later the cops make quick, brutal arrests at a drag variety show. At the police station, the cops pull Jess out of the holding cell first. They taunt her and yank at her clothing. Jess is severely beaten when she refuses to perform fellatio on an officer. Jess Is then dragged to a befouled toilet where her head is shoved in. Jess throws up and is then cuffed to a desk and raped in both orifices.

While Jess works at a bar, Toni bursts in, drunk. She thinks that Jess is having an affair with Betty. Jess refuses to fight Toni; she is grateful for being allowed to stay in her home. But Toni abruptly withdraws Jess's welcome. All Jess can do is pack her pillowcases and look for a new home. Angie, one of the pros who is a regular at the bar, offers Jess a place to stay for the night. Angie suggests that Jess get a job at a factory—not in order to grow up, but to stay young. Hanging out at the bars too much will age a person fast.

Angie sees that something awful has happened to Jess. Angie embraces Jess, and Jess feels her emotions come out without words. This is only the start of something larger. Tonight, Jess loses her butch virginity. Angie says it is okay for a butch to ask for what she needs from her femme, that a butch doesn't always have to be stone. Jess understands, but this is another one of those lessons that is harder to practice than it is to preach.

Jess learns the tricks and traumas of factory work. Friendship among coworkers is wary but when camaraderie is present, it's the best part of the day. Workers come in early in order to have communal coffee and rolls before the whistle blows. They talk to each other as much as they can outside the foreman's notice, to prove that the factory only rented their hands and not their minds.

One day Jess joins in a morning song with some of the other women. Jess is terminated before lunch and wonders if this has anything to do with her singing. Management doesn't like a unified workforce. Jess walks home, thinking that all she has to look forward to is lame holiday specials on television. But Muriel, Yvonne, and the other women of the factory come by with food, gifts, and an invitation to a party. The end of the job doesn't always mean the end of the group.

Jess usually works in the trimming and folding division at a bindery, where paper is cut and collated for booklets. One day, the foreman Jack takes her off that task in order to learn how to use the folding machine. Duffy, the chief shop steward, pulls Jess aside and tells her the real reason she's being considered for this Grade Five job is that Jack is collaborating with Jim Boney in order to keep the job from Leroy, a black worker, who is the only man in the bindery still stuck at Grade Four—and it's not because of his qualifications.

Jess feels hurt; she knows she deserves this job, too. Duffy convinces her to let Leroy have this one, and he will find another Grade Five job for her when it's available. Union solidarity is more important than ever now. The union's contract with the bindery will expire in a couple months, and worker dissension just puts management in a stronger position. Duffy also promises to get the butches into the union meetings; at the union hall, they are not allowed to go upstairs to attend the meetings, because "that's the way it is."

One day Jess is injured on the die cutter machine and after being treated at the hospital, Duffy tells her that she has not lost her finger. Jess gets a prescription for painkillers and Duffy takes her home.

When Jess talks to Duffy next, he says that Jack set her up to be injured. He had the safety device removed and provided inaccurate instructions. Once again, someone has used his power to control her life. Duffy also says he was enraged at the way the doctors talked to Jess—as if she were a freak with no humanity. Jess is amazed that a straight man would stand up for her.

Jess learns that Jan and Edna are no longer together, and that it's Jan's fault. Jan just could not let Edna touch her like a lover. If she could see Edna again, Jan would beg to have her back, but she doesn't know how she can break down the stone inside her. Jess knows how that feels. She fears that her own lovers would leave for the same reason. Suddenly, a figure comes into the bar—a large, flat-chested, leather-jacketed woman with riding gloves and helmet. This is Rocco, a butch legend in Buffalo. Edna and Rocco used to be lovers before Edna met Jan. Jess wishes Edna would look at her the way Edna looks at Rocco. Jan said that Rocco is taking hormones, had her breasts removed and is passing as a man in public.

When the strike at the bindery is on, it's time for the union to stand up and try to keep the scabs out. They shout insults at the strikebreakers. The cops are there to make sure the scabs get into the bindery. When a scab senselessly strikes Frankie with a blackjack, Jan hits him over the head with her picket sign. The cops grab her, as well as three of the workers who jump to her aid. They take them all to the police van. Jess panics; she knows what will happen to Jan at the police station. The strikers surround the police van and rock it back and forth forcing the police to release Jan and the three men.

The strike at the bindery is successful. Duffy asks Jess to bring all the butches from the plant to vote at the ratification meeting. But Grant has interesting news: The steel plant must hire fifty women. How could the butches pass up this opportunity? Steel is a solid job, and its union is powerful. Duffy thinks it's a huge mistake for the women to leave. The steel plant has to hire the women, he says, but they don't have to keep them for the ninety days it takes to get into the union.

The butches wait on a long cold night to be among the first fifty to get in the steel plant. On the first day of work, the foreman gives the women shovels and points to some railroad tracks. Their job is to shovel the snow off miles of tracks. Jess and Jan quit immediately. In the morning, a shamefaced Jess stands outside the bindery and waits for Duffy to arrive. She tells him he was right about the steel plant.

Jess feels guilty about dating Edna and being friends with Jan at the same time, even though she didn't steal Edna away from Jan. Eventually, she tells Edna that it doesn't feel right between them, not because Edna is older, as Edna had feared, but because Jess feels she must mature before she is ready to be Edna's lover, and she doesn't want to hurt Jan in any way. Edna says she sees the same loyalty and honor in Jess that she saw in Jan and Rocco. They part with a kiss.

Ed invites Jess to have breakfast with her and Darlene at a diner popular with butches, drag queens, and pros. Among the crowd, Jess sees a beautiful pro, Milli, who flirts with Jess who offers Milli a brown leather jacket, and they take a ride together, which translates as butch-femme courtship. Milli is a tough stone pro, a thrilling match for Jess's own strength.

Milli stops working the streets, while Jess takes a job at a pipe factory. When Jess loses that job, Milli talks about taking a job dancing at a nightclub. Jess is furious and Milli's responds that nobody tells her how to run her life. Jess counters that Milli is just waiting for her to say one wrong thing about her being a pro so Milli will have an excuse to leave. Milli says that stone pros and butches fit together like puzzle pieces; the world has hurt them the same, and butches are tender in bed in ways that most men are not.

When Milli comes home on a Sunday morning with a swollen face and split lip, Jess is distraught. Milli says that when Jess said she would protect her from danger, it's what anyone in love would say or want to hear. But in the real world, butches and pros can't protect each other no matter what they promise. After a brutal fight, Jess feels she must go to Milli and apologize, even if it means entering the Pink Pussy Kat club. Jess is amazed that Milli dances nude in a cage. But she also knows that coming here was the mistake that will tear her and Milli apart for good. When Milli comes home, she is furious with Jess and packs her bags, but not because Jess came into the club. They were a good couple, but sooner or later they would destroy what was good about them.

One day Jess finds Ed at her home dressed for a fine occasion. Ed informs Jess that Butch Ro, the elder's elder in the butch community, has passed away and her funeral is today. All of the old butches are wearing dresses for the occasion to comply with Ro's last wishes. But Ed is not going to and Jess can't because she doesn't even own a dress.

Later at a local diner, Ed and Jess get the cold shoulder from the older butches, who had changed back into their regular clothing. Ro's femme Alice stops at Ed and Jess's table. Despite her own grief, she patiently explains that the old butches thought that Ed and Jess should have been willing to wear dresses, if only to show respect to Ro. It will be a long time before either of them will be welcome around the old butches.

Jess and Jan find new jobs at a cannery where Jess spots a striking woman. Jess discovers that her name is Theresa and she starts each day eager for a glimpse of her. Theresa is fired for kicking the superintendent in the shins for trying to grab her breasts. Jess is proud that Theresa defended herself but despondent that she is no longer in the factory.

One day Theresa shows up at Abba's. Jess is overjoyed but plays it cool. Jess and Theresa soon move in together and Jess learns how to be a responsible partner—not only paying bills and cleaning, but saying "I'm sorry" and allowing Theresa to tend to her wounded parts. When they have been together almost two years, Jess buys Theresa a gold ring with a diamond and two rubies.

After being arrested in a bar, Jess is severely beaten and drifts in and out of consciousness waiting for Theresa to come pick her up. At home, Theresa gives Jess a bubble bath and clean clothes as usual. What is worse than the physical pain is remembering the horror on Theresa's face. It is easier for Jess to hold in her own pain than to witness Theresa's.

Theresa becomes more involved with campus politics. She says she is learning so much about being a woman. Jess says she hasn't given women's issues a thought because she's a butch. Theresa says that all women could learn from feminism, namely, how to treat each other better.

Jess has been out of work for quite some time, and her unemployment insurance is about to run out. Then Theresa loses her job at the university. Money is short and so are their tempers. When Jess goes to the temp agency, the men blame her and women like her for stealing their jobs.

At the bar, Grant tells about a butch, Ginni, who's on the sex-change program and is now Jimmy. Ed says that she has started taking male hormones. When Jess comes home and tells Theresa what the butches talked about—and that she is considering taking male hormones—Theresa doesn't know what to say. Finally, Theresa blows up; she loves Jess because she's a woman, too. If Jess takes hormones, the woman Theresa loves will go away. Jess says she doesn't know what else to do.

Theresa gives her the real reason she's afraid of Jess taking hormones—she has come too far in accepting her own desires, in being happy to walk down the street arm-in-arm with Jess, to have Jess turn into an ersatz man. Jess pleads that she needs Theresa. But they're in an impossible situation; Jess can't survive unless she changes, and Theresa can't live with Jess after she does. Theresa asks Jess to leave.

The next morning, Jess sees Gloria, her friend from her first job. Gloria has two young children now, Kim and Scotty. Gloria offers Jess a place to stay until she can find a new apartment. The children look upon her with curiosity. At a pizza shop, Jess is harassed by some jocks and she is forced to abandon her Norton and start running. When she returns to the parking lot, the Norton is totally destroyed. Jess has to take the bus to Gloria's. Gloria allows her to make a call to Ed and Ed says that Darlene has left her and taken the car, as a gift from Ed.

Jess and Grant go together to the doctor who prescribes hormones. To "celebrate" this life-changing decision, the two go out for drinks. Grant asks a question that Jess had never thought of: Will any woman want to go out with them after the hormone treatment? Grant says her life is a mess, but she has nowhere else to turn. Cryptically, she says that she's not a real butch—what that means, Jess doesn't know. She wonders if Grant is taking the hormones to prove otherwise.

When she is at home alone, Jess stares hard at the syringes. She is afraid to push the needles underneath her flesh. She is afraid that Grant is right; she remembers the tender warmth of Theresa's arms. Then Jess grows angry. This is her decision, and hers alone. Jess injects the hormone. It isn't as scary as she thought it would be. Maybe this is the first step that will let her just live for once and not have to fight for the right to exist every day.

Jess looks in the mirror one spring morning and sees stubble sprouting on her face. Her body is losing feminine curves and gaining muscle. This is the body she wanted to have before puberty—except for her breasts. Now she can afford breast-reduction surgery. Jess braves a visit to a barbershop out of her normal neighborhood. When the barber calls her "sir," she knows she has passed.

Jess sees Gloria shopping with Kim and Scotty. Gloria pulls Kim and Scotty closer to her, as if Jess were a monster. She calls Jess "sick" and gets away from her as fast as she can, despite the children wanting to see Jess again.

Jess buys a new Harley Sportster and drives up near the Peace Bridge to Canada. She looks at her driver's license with the sex labeled "Female". How in the world can she use this license and risk showing it to an officer? How in the world can she have it renewed with "Male"? How can she open a checking account without accurate ID?

Jess grows a beard that she can effectively hide herself behind in public. She goes in for her breast-reduction surgery. The doctor she has made an appointment with isn't there, and the staff is unhelpful at best and hostile at worst; they do not approve of this doctor's arrangements with "you people". After the surgery, Jess doesn't want to be in this place another minute. She goes home with a handful of Darvon, thanks to one sympathetic nurse.

Jess is riding on a bus filled with temp laborers. One of the men on board, Ben, is a regular, just like Jess. Ben invites Jess for a drink after work and Jess agrees. Ben starts opens up about his personal life—caring for a daughter with Down Syndrome, being arrested for stealing a car in his youth, ending up in jail at the mercy of brutal guards.

Jess is grateful for the gift of Ben's intimacy. She wishes she could open up to him the same way. Years of societal abuse have made the walls surrounding her heart too tall to climb, from inside or out. How can she tell Ben her one great secret—she's not a man? All Jess can say about herself is "There's nothing to tell" (page 185).

Jess notices Annie, a waitress at the coffee shop near her work, and asks Annie for a date. For the first time, she has public approval for her courtship. Of course, the public sees a man with a woman and so does Annie. Their first date takes place at Annie's home because the babysitter of Annie's young daughter, Kathy, is sick. When Kathy is in bed, Annie says that she can't quite figure Jess out, and "a man you can't figure out is a dangerous man" (page 189). Jess says she's not dangerous, just complicated. All she wants is some comfort. So does Annie. In the morning, Annie invites Jess to attend her sister's wedding. Jess agrees, picking Annie up on her Harley. At the reception, all goes well, until Annie notices a man she's familiar with and calls him a "fag." According to Annie, "queers" molest children. Jess says that a straight man would be more likely to molest Kathy. Fueled by champagne, Annie says that her ex-husband molested Kathy, so she's not letting any "funny men" near her daughter. Jess knows that she and Annie can go no further.

Jess is at work again and fits in with the men so much that she can go into the men's bathroom and locker room without comment. Instead of hanging a pin-up of a woman in her locker, Jess has a magazine ad for the Norton she used to ride.

Bolt says to Jess that a new worker knows Jess—Frankie, who was with Jess at the bindery. Jess panics until Bolt says that Frankie called her a "good union man." This factory is non-union, but the employees want that to change, and soon. The wages are low compared to union factories; overtime is not paid, and conditions are hazardous, both from the ill-maintained machines and the toxic fumes. When Jess meets up with Frankie again, all is well until Frankie reveals that her new girlfriend is Johnny, another butch who worked at the bindery. Jess can't believe it. How can two butches be romantically involved?

After a worker named George is severely injured on a forklift with faulty brakes, which Bolt had warned management about, it's time for a union organizing meeting. Jess is surprised to see Duffy at the meeting; he is the one who will organize the computer plant workers. The meeting goes promisingly, until Duffy points out Jess and says, "She's proved she's for the union 100 percent" (page 206). That kills her job at this factory.

One day, Jess sees Edna, Butch Jan's lover, working as a cashier. It has been about twelve years since Jess saw Edna. Then, Jess thought she was too young to be a decent lover to Edna. They meet outside the supermarket when Edna's shift is over and Jess and Edna ride together to the zoo. Jess is so happy to share her motorcycle with a femme again. At the zoo, Edna tells Jess that she is not seeing anyone now. They kiss and make a date for next Friday night.

On their date, Edna asks Jess how it feels to pass as a man. Jess says it's nice to have people look at her as a real person instead of a freak. But passing has also made her invisible; it has robbed her of her history. Edna understands, because she was Rocco's former lover. Edna says that the femmes don't see butches as a homogeneous group. Edna calls Jess and Rocco "granite" butches—the ones who are hardest on the outside are also the ones with the most fragile hearts. Edna gives Jess Rocco's leather motorcycle jacket—"armor" for protection. But Rocco's jacket can't protect Jess from falling in love with Edna again. Edna loves Jess, too, but she cannot consummate the relationship, and she has no words to tell Jess why. Jess thinks this is a rejection of her, but Edna says no. The problem is inside her, says Edna, and not even a butch's strength can fix it.

Jess sees Theresa and her new lover at Kmart. Jess is furious with this butch she does not know. She needs Theresa's love more than any rival could. But going back to Theresa means exactly that—going back. Jess sees that she and Theresa were not on equal terms: she had been the center of Theresa's life, but Theresa had been her whole life. She had needed Theresa so much—but she couldn't give Theresa what she wanted most, a rope to climb the fortress to her heart.

Change happens slowly after Jess stops taking hormones. Jess's face is smooth again like a woman's. She has rounded hips like a woman's. But she also has the flat chest and the deep voice of a man; the voice is something that doesn't come back as it was. She can no longer pass as one gender or the other; she has entered the world of difference for good. Other people don't know what to think.

Jess no longer has a good reason to remain in Buffalo. Her friends have either died or have left her life under bad circumstances. She can find work easily in Manhattan. She will also have anonymity—no one will know who she had been before; the face and body she presents now is all New York City will see. But when no one knows you, no one will pick you up if you fall. It takes the theft of her Harley to convince Jess that she has had it with Buffalo. She hops on an Amtrak train and takes it all the way to New York City.

Jess arrives in New York City with $600 in her pocket, and that will have to get her an apartment, which, she soon realizes, is an overwhelming task. Needing shelter for the night, Jess goes to an all-night movie theater on 42nd Street. The next morning, Jess goes to an apartment rental agency, which finds her an apartment for $250 a month, plus a security deposit and a finder's fee. The apartment turns out to be a single room—no stove, refrigerator, running water or a door that locks. When she hears footsteps pause outside her door, she knows she can't spend the night in her own apartment.

In order to earn enough to get out of her lockless room, Jess holds two jobs at a time. She washes her shirts at Grand Central Station just like the homeless. Jess moves into a new apartment, this one with a kitchen and locking doors. In time, she paints the walls and sands the floors, and puts yellow calico curtains on the windows, just like the kind Betty had. On the mantle, she adds a china kitten that was a gift from Milli, as well as the ring that Theresa had given her. She finds a couch, a chair, a bed, and a rug. She puts down roots in this apartment.

Jess puts her fledgling typesetting skills to work. New York teems with typesetting shops, and the shift that pays best is the night shift. Jess's skills grow along with her salary. In the summer, the shops cut back on their workforce, but Jess still gets a substantial unemployment check. She has money in her pocket and an attractive place to live, but she is lonelier than ever.

As Jess comes home from working out at her gym late at night, she sees water in the street and the spinning red lights of fire engines. An apartment building has become a tower of flames—her apartment building. Everything inside—the ring Theresa gave her, Milli's silly china kitten, the book by DuBois that Ed had signed, Jess's wallet, last paycheck, and the only photo of Theresa she has left—is gone.

Back on the street, worrying over the hard work needed to start all over again, Jess sits on a bench in Washington Square Park. She sees a man juggling torches and wonders what it would be like to have a skill with no practical value, something you did just because of the joy it brought. A man standing next to Jess comments on the performance without words. He is deaf. Jess keeps an eye on him as he juggles imaginary bowling balls, his gestures creating the form of the balls. Jess laughs out loud and cries as well. Her emotions are thawing at last.

Jess finds a one-bedroom apartment although she doesn't have the heart to clean it or put real furniture in it. A month after she moves in, Jess finally sees her neighbor, a woman with bright red hair, a severely bruised face and an Adam's apple. The neighbor, Ruth, is prickly at first. When Jess tries to help her carry her groceries, Ruth retorts with, "Where I come from, men don't reward women for pretending to be helpless." (page 248)

Inside Ruth's neat, painting-filled apartment—watercolors of dainty flowers—Ruth tells Jess that she was born in Vine Valley, grape country, about two miles from Buffalo. Knowing Ruth is nearby brings Jess back to life. Once again, she seeks out small good things, such as fresh fruit and jelly and music, this time a Miles Davis concert tape for Ruth. In turn, Ruth gives Jess home cooking and salad tossed with nasturtium flowers. Each of them has found a kindred spirit—a mirror image, reversed yet the same.

In the real world, it is dangerous for Jess and Ruth to be seen in public together, because two of their kind are "double the trouble" according to Ruth. Jess asks why change for them is not coming quickly enough. Ruth reminds her that not too long ago, black people risked their lives for simple rights, such as sitting at a lunch counter. It is not too late for people of their kind, too.

It is winter, and Jess stands on the subway platform when three teenage boys, high on drugs and looking for a fight, enter the subway station. Jess turns the keys in her hand into a spiked weapon. She has had enough of powerlessness. If these boys attack her, she is going to do her damnedest to take them down with her. She manages to strike two of the boys before one of them hits her, breaking her jaw. Jess gets on the train, horrifying the other riders with her blood-saturated face and stops at St. Vincent's Hospital, inventing an identity as a man with insurance so she will be treated right away. A doctor sews Jess's broken jaw shut with wire, rendering her unable to speak. A nurse says that Jess should stay overnight for observation, and also that she needs to file a crime report as required by law. Jess fears that the police will not only discover that she is uninsured, but that she is a gender outlaw. Jess escapes the emergency room and takes a cab home.

Ruth is horrified and cries when she sees Jess's condition. This is why she had been reluctant to bring Jess into her life because she can ignore her own bruises, but not those of someone she cares about.

Jess remains at Ruth's apartment for days, slipping in and out of consciousness. Ruth comes in and says she has made a terrible mistake. She called Jess's employers to inform that Jess is incapacitated, but used the personal pronoun "she"—just as Duffy did in the 1970s. But it doesn't matter now. Jess asks for a pen and paper and writes this message to Ruth: Thank you for your love. When Jess is able to work again, it is a month and a half until Christmas, and the print shops around town hum with activity. By day, she works out in the gym, expressing her silent rage. For most of her life, fear has kept her mouth shut as surely as the metal wires are doing now.

Jess has earned enough money before the holidays to buy Ruth a special gift—a new sewing machine. She cuts the wires in her jaw by herself. On Christmas Eve, Jess goes to Ruth's and Ruth's drag friends, Tanya and Esperanza, are there, too. Tanya flirts with Jess. Ruth is quite pleased with Jess's gift and has two of her own for Jess—a book about gay American history, which discusses transgender history as well, and a painting of Jess looking up at the stars.

One day, when Jess returns home, Ruth reveals a surprise—she has painted the ceiling of Jess's bedroom the color of the night sky, with bright stars and the silhouettes of trees. The edges of the ceiling-painting are lighter. Jess wonders if this sky is supposed to be dawn or dusk. Ruth says, "It's neither. It's both" (page 269)—words that can also describe Ruth and Jess themselves.

Asking questions about the distant past gets Jess thinking about her own. She wants to find out what happened to Butch Al. She wants to see Kim and Scotty again, as she had promised. She wants to apologize to Frankie for being upset that she had a butch lover. "I always wanted all of us who were different to be the same," she admits (page 271). She wants to write a letter to Theresa that will express her feelings at last.

Jess calls Frankie to apologize. Frankie is going to be in Manhattan, so they plan to meet outside a lesbian bar in Sheridan Square, outside, because Jess isn't sure that she would be accepted in such an establishment now. When Jess and Frankie reunite, Jess asks what is going on with their old gang in Buffalo. Frankie says she sees Grant a lot, and Butch Jan has opened a flower shop. No sign of Theresa, but Frankie says that Duffy feels horrible about inadvertently sabotaging Jess's job at the computer parts factory. Jess asks Frankie for Duffy's phone number.

Jess says that Frankie taking a butch lover shocked her because butch-femme love was a beautiful thing that mainstream society did not honor. Frankie says that Grant taught her that she didn't have to prove her "butchness." It took a long time for her to accept her attraction to butches—just as some gays take years to accept their orientation in general.

Jess plans to take a trip to Buffalo to get in touch with her past. She wants to take Ruth with her because Ruth's home is nearby but Ruth is reluctant to go home again. She has as many bad memories of her family as she does good, and she worries about how her family will react to Jess. Jess convinces Ruth to travel with her by saying, "Neither of us wrestle that hard with things we're not ready to take on" (page 278).

In Buffalo, Jess goes first to the apartment building where she and Theresa used to live. Theresa isn't there anymore. Jess calls up Gloria, hoping to keep her promise to Kim and Scotty. But once Jess says her name, Gloria warns her to stay away from her children. Her next stop is the flower shop that Butch Jan owns. She is startled to find Edna working behind the counter. She feels a pang of jealousy; it's obvious that Edna and Jan are lovers again. Jan is in the greenhouse, a little grayer. She recognizes Jess at once and gives her a warm greeting. Jess asks Jan if she knew what happened to Butch Al. Jan replies that Edna knows an old friend of Al's. She also invites Jess for drinks with what is left of the old gang.

Jess sees Edna and Jan, as well as Frankie and Grant. Jess asks Edna where Butch Al is now. Edna says that "some things are better left alone" (page 284). Jess is tired of other people taking away her power. She can't find Theresa, and Gloria is keeping her from Kim and Scotty. She will not leave without seeing Butch Al. Edna says that Al is in the asylum.

Posing as Al's nephew, Jess appears at the medieval-looking asylum. Al is seated in front of a window, white-haired and catatonic. When she uses the name "Butch Al", Al grabs her arm. "Don't bring me back," she warns. Jess sees that Butch Al has gone underground to protect herself from the world, only in a far more drastic way than Jess did. Jess tries not to upset Al too much, but does what she came here to do—to tell Butch Al how much she appreciates and loves her. When the visit is over, both are in tears. When Jess returns to the flower shop, she meets an upset Jan.

Jess finds her voice at a gay pride rally where she says that as a "he-she," she wonders if she is welcome as part of the gay movement. "Couldn't the we be bigger?" she asks (page 296). If gays and the transgenders raised their voices, it would only make a bigger impact. After she speaks, people of all types, gay men, drag queens, butches come to praise her words.

Duffy is now a union organizer. Jess had not seen him since he inadvertently revealed her true sex and cost her a job. He asks Jess if she would like to be a union organizer, too. It's difficult for Jess to see herself as a leader, but if she can speak out in public the way she did today, anything is possible.

Jess wakes up and sits on the fire escape. Everything she has experienced since receiving the ring made her the person she is today, and for the first time, she has no wish to change the past. In the distance, someone releases pigeons from a rooftop. They beat their wings and lift themselves into the sky.

Characters

Jess Goldberg

The protagonist and narrator of Stone Butch Blues. The novel is her autobiography from birth to early middle age.

From a childhood of shame and ridicule for simply being herself—a girl with too many masculine characteristics for society's taste—to an adolescence and young adulthood marred with beatings and rapes, Jess is a walking contradiction, a tough and taciturn butch on the outside, frozen with helplessness and terror on the inside. Jess is no coward, but the implicit and explicit messages of hate she receives nearly every day hardens the stone around her heart because of the human reflex to protect oneself. Unfortunately, this impulse is difficult to turn off, even with lovers.

When Jess makes the most important decision in her adult life—taking male hormones in order to pass as a man, it separates her from the Buffalo gay community and from her one great love, Theresa. Jess grieves both of these losses, but she thinks that the hormones are the only way to salvage her life, the only way to stop the everyday battering. As a "man," people will stop wondering about her sex. She'll finally be treated as a human.

Once she begins to pass as a man, Jess is happy to be able to enter the all-male domains of the barbershop and the men's room; finally, she doesn't have to endure dirty looks for going into the women's room. But passing has its price. Jess not only loses her old community but cannot make new friends because now she has to hide the secret of her biological womanhood.

Jess learns that she is in truth neither all-woman nor all-man; she is transgender. The world, even now (Stone Butch Blues ends at the end of the 1980s) doesn't always know how to treat transgender people, but Jess is through with hiding and lying. She has found her voice, and no matter what lies ahead, she's not letting it go.

Jess's parents (unnamed) and younger sister Rachel

Jess's mother and father had hoped for a life above the ordinary. When they marry and have their first child, their lack of imagination makes them drift into the roles they dread most—factory worker and housewife. They are scared and furious with Jess's gender "deviance" and react with bewilderment, rejection, punishment, and banishing her to ineffectual psychiatric treatment. Rachel is the "normal" daughter, who dreams of growing up to be a teen queen in a poodle skirt. When Jess runs away from home shortly before her sixteenth birthday, her parents don't come after her, and neither they nor Rachel appear again in the narrative.

Mrs. Noble

Jess's high school English teacher. She sees the poetry in Jess long before Jess herself does. She is saddened when Jess announces she's going to drop out of high school. She knows that Jess is smart enough to go to college, but to Jess that is a financial impossibility.

Gloria

Jess's friend at her first job. She has a brother who dresses in women's clothing. When she says there's a bar that her brother goes to in Niagara Falls, Jess wants to know the name of that bar. By telling Jess about Tifka's and later Abba's, Gloria introduces Jess to a community of butches and femmes, which sustains Jess throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. Years later, when Jess moves out of Theresa's apartment, she temporarily stays with Gloria and her two kids, Kim and Scotty. Jess falls in love with the kids, but when she starts changing due to the hormones, Gloria wants Jess to stay away from her family. Ironically, Gloria felt sympathy for her brother, and said "it's not his fault he's that way" (Chapter 2, page 26)—an enlightened attitude for the time.

Butch Al

The first real butch Jess gets to know. Al is the alpha butch at Tifka's, and everyone knows (except Jess when she first comes in) that no one asks Butch's Al's femme, Jacqueline, to dance. Butch Al becomes Jess's first mentor, and her main lesson is to "toughen up." That is a necessary lesson for a butch in a world where a fist or a nightstick might come crashing down on your head at any moment. Al also teaches Jess the use of the dildo, though Jess has never seen one before and knows almost nothing about sex—either gay or straight. When Al and Jess are caught up in a police raid, Jess is shocked at Al's appearance after the police drag her back into the cell. Al is disheveled, bloodied, silent. All Jess can do for her is give her an embrace. Soon afterwards, Al disappears from Tifka's. Near the end of the book, Jess reunites with Butch Al in an asylum in Buffalo. Jess can now tell Butch Al how much she appreciates her. Butch Al can barely move due to a stroke, but she still hears. And remembers, even if just a little bit.

Jacqueline

Butch Al's femme, a "pro" (prostitute). She is also a role model for Jess in that she is the perfect description of a femme—long nails, high heels, and a sweet demeanor. Butch Al teaches Jess about the dildo, but Jacqueline says it's not how you use it that counts, it's the thought behind it. A butch must be careful with the feelings of a femme. But femmes are the strength behind butches, too; no one is strong enough to handle the streets alone. After Al disappears, Jacqueline ends up as a heroin addict, proving her lesson.

Bobby

The leader of a gang of football players who gang-rape Jess on the football field. This is Jess's first experience of sex, and it is more like "making hate" than making love (Chapter 3, page 41). The rape is one of the factors that leads to Jess dropping out of high school; soon, most of the kids know about it, and it is certain to happen again.

Karla

Jess's friend at high school. When Jess sits down at Karla's table at lunchtime, everyone in the cafeteria freezes. Why? Karla is black, and the cafeteria is strictly segregated—that's the way most students want it, and that's the way the principal, Mr. Donatto, wants it, too. Jess is suspended for one week simply for sitting on the black side. Of course, Karla gets suspended for two weeks. This injustice, along with the rape, makes Jess decide that she can no longer stay in this school another minute.

Ed (Edwin)

A strong, proud black butch. Ed takes politics personally—it's impossible not to when centuries of racism and injustice finally raise the fist of Black Power. Ed is a target of discrimination on three fronts—as a black, female, and lesbian. Ed gives Jess The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. DuBois, which describes the dual citizenship of black Americans—a parallel to Jess's dual "citizenship" as male and female. Ed is one of the butches who takes hormones, and it has a devastating effect on her life. Her longtime lover, Darlene, leaves, and Ed feels even more distant from society as she straddles the line between male and female. Tragically, Ed ends up shooting herself. As with Butch Al, life can take down the strongest of butches.

Butch Jan

Another of Jess' butch friends in the Abba's crowd. Like Jess, Jan is a good-hearted woman, who has built up stone walls around that good heart. Jess looks up to Jan as an elder, but their relationship is complicated because of Jan's femme, Edna. Jess develops a powerful attraction to Edna after Edna and Jan break up. But Jess is afraid to go too far with Edna because she doesn't want to hurt Jan. Near the end of the book, when she goes back to Buffalo, Jess reunites with Jan at her flower shop. Jan is angry with Jess for having an affair with Edna more than a decade before. Jess is angry with Jan for being with Edna now. But it's all just water under the bridge now. Jess and Jan end up agreeing that love—and friendship—are rare gifts in a cruel world, no matter where you find them.

Edna

Butch Jan's femme. Edna's departure from Jan breaks Jan's heart. When Jan says that Edna can seduce any stone butch love, it awakens Jess's sexual interest in Edna. At first, Jess can't get together with Edna—she feels she's too young, and she's concerned about how Jan will feel. Years later, after Jess starts taking hormones and drifts away from her old crowd, she meets Edna at a supermarket. Both of them are lonely, and they fall into each other's arms. Edna can't fully give herself to Jess. She's in an emotional "deep freeze," just like many butches and femmes are. Jess wants to beg her to stay, but knows it won't work. Years later, Jess comes to Buffalo to see about old friends. She finds Edna at Jan's flower shop—they are lovers again. Jess can't believe it—was it really her that Edna had rejected? But Jess realizes that life is too short to let jealousy interfere with the greater good of reconnecting with the Buffalo community.

Angie

Jess loses her butch virginity to this femme. When Jess sees the dildo in Angie's hands, she's so grateful to hear these words from Angie: "I'll show you how." (Chapter 6, page 71). Contrary to Jess's expectations, it's her inexperience that excites Angie the most. Angie is another "pro," who has seen the back side of life, and she advises Jess to get a job and not spend too much time in the bars because that is the path to aging before your time.

Grant

Another of the butches with whom Jess works and hangs out. Even though Grant is outside mainstream society like the other butches, she is hardly progressive; after her brother is killed in Vietnam, she says the U.S. should just drop an A-bomb on it. She has a dust-up with Ed over Dr. Martin Luther King. Her bravado is fueled by alcohol; when she is drunk, she might say anything, including that she's not a "real" butch; perhaps, as Frankie hints, because she fantasizes about being with butches herself.

Frankie

One of the younger butches in Buffalo. Frankie stuns Jess when she says that she's involved with another butch, Johnny. Jess can't believe it—two butches together are as inconceivable to her as a same-sex couple would be to many heterosexuals. Jess asks Frankie, "What makes you think you're still a butch?" (Chapter 18, page 207). Years later, Jess knows she was wrong and apologizes to Frankie. Jess and Frankie agree that femmes have their own language for their feelings, and sometimes, only a butch can know butch feelings.

Peaches, Justine, Georgetta, Tanya and Esperanza

Men who dress as women—if they are gay, they are called drag queens—appear throughout the narrative. Drag queens go to the same bars where butches go. Even though they are the polar opposite of butches, the two groups stand up for each other. The queens can teach baby butches a thing or two about femme psychology. Non-cross-dressing gay men do not play a significant role in this narrative.

Duffy

The chief shop steward at the bindery in Buffalo, the first and only place (so far) in which Jess is a member of a union. Duffy is a man of consummate fairness. He believes that everyone has a right to work with dignity and safety, regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation. Jess learns how to be a good "union man" with the example of Duffy's loyalty. Duffy also learns from Jess that justice can't wait. If he had tried to get the butches into the bindery union meetings, maybe they wouldn't have left to get jobs at the steel plant.

Those who are against the union and/or dislike Duffy's attitude toward minorities spread rumors that he's a Communist—a major liability in the Cold War 1960s. Is it true? At the end of the book, Duffy says that it depends on how you define "Communist"—a word, like "racist" or "liberal," that is defined by the limits of one's anger.

Rocco

A giant, leather-clad butch who comes into Abba's like an apparition out of time. Rocco takes male hormones and can pass as a man and is the first person Jess meets who has taken this step. Their meeting is brief, but Jess carries Rocco's example with her for years to come. Rocco is Edna's former lover, and Edna says Jess and Rocco have much in common—weariness, loneliness, and a secret vulnerability. It's the tough ones who hurt the most. Edna bequeaths Jess Rocco's leather jacket, which was her "armor."

Milli

A "pro" femme, the first lover with whom Jess lives. Milli is sexy, yet tough; Jess knows it when Milli gets behind Jess for a ride on the Norton shortly after they meet. Jess feels super-protective towards Milli, especially after she is beaten by an off-duty cop. But when Jess objects to Milli dancing in a nightclub, Milli makes it clear that no one tells her what to do or where to work. Milli says that she has more solidarity with the other dancers in the clubs than with the regulars at Abba's. There's a difference between a woman who turns tricks to pay the rent and a stone pro who's into the life. This relationship cannot last, because, as Milli says, she and Jess can't protect each other, and they would end up breaking everything, including and especially each other.

Theresa

The one great love of Jess's life. Theresa has everything that Jess wants and needs—beauty, femininity, and a gentle healing touch when Jess comes home battered. For the first time, Jess enjoys true domesticity at the apartment she and Theresa share. When Theresa gets a job at the local university, it introduces her and Jess and the Abba's crowd to the new feminist movement, which has no place for butches and femmes. It pains Jess that she can't fully express herself, even with Theresa. But it's Jess's decision to take male hormones that tears them apart. Theresa has worked too hard to develop self-respect as a lesbian to pass as heterosexual by being with a woman who's passing as a man. Losing Theresa is the most grievous wound in Jess's life. It takes years before she can write a letter to Theresa, the letter which begins the book.

Kim and Scotty

Gloria's two young children. Scotty is too young to notice Jess's gender, but Kim has many questions—like how can two "girls" be married, and why did the man at the zoo call Jess "sir"? Jess teaches the children that people should be free to be who they are and love who they love. The purity of these children's love is the one bright spot in Jess's life. But when Gloria sees that Jess has taken hormones, she tells Jess to stay away from the children—on two occasions, years apart. Jess made a promise to Kim and Scotty to see them again—whether or not she will see them again is one of the novel's unanswered questions.

Ben

A guy who rides with Jess on a temp worker bus. He has a history with a few dark paths, including time in prison. Ironically, Jess cannot open up with this man who is opening as few men do because of her greatest secret: She's not the man that Ben thinks she is. Her experience with Ben shows how taking the hormones has further alienated her from people, even people who don't know her from before.

Annie

A waitress and single mother who becomes smitten with Jess. Like Ben, Annie thinks that Jess is a man. Jess knows that this is a dangerous relationship for her, but she is so starved for touch that she takes the risk. A darkened bedroom and a dildo help Annie to believe that she has made love with a cisgender man. Jess knows this is only an interlude, a fact underlined when Annie rants about "faggots" at her sister's wedding. Jess isn't angry with Annie; she just doesn't want to be just another one of the betrayers in Annie's life.

Ruth

Jess's next-door neighbor in the third apartment Jess has in New York City. Like Jess, she lives between two genders. She is tall and big-boned, yet she has bright crimson hair and is gifted in traditional feminine arts such as cooking and sewing. When Jess meets her and offers to help with her grocery bags, Ruth insists she is not weak. She keeps distant from Jess while Jess wants to be her friend more than anything. They finally connect over a harvest moon—Jess learns that Ruth is from upstate New York, like she is.

Ruth introduces Jess to the small joys in life, such as colorful nasturtiums over salad and elderberry pie. And the big joys—such as learning from a gay history book that trans individuals have a long and honorable history. Ruth shows Jess that it is possible to live between genders and accept who you are without waiting for validation from family or society. She's the friend we all wish we had.

Themes

Being Different

Jess and her lesbian/transgender friends are different from what the greater society says they should be. The butch women do not wear dresses or skirts and do not hold back their physical strength in order to sooth men's egos. The femmes choose butches as their mates instead of legal marriage to men. The drag queens reject pants, short hair, and the dull blues and grays of traditional male dress.

Because these people choose to express the difference on the outside that they experience on the inside, society's reaction is swift and severe. At best, butches, femmes and drag queens get looks of disgust. At worst, they are raped and beaten to the point of death.

When you are battered on the outside, it cannot help changing you inside. With every attack, the stone around Jess's soul becomes harder. Even among her dearest friends and the love of her life, Theresa, she keeps her secret self hidden behind that stone—it's the only place where it is safe. As a result, she cannot completely feel the love that others give her.

Jess thinks that taking male hormones and having breast reduction surgery, which allows her to pass as a man will make her life easier. She is wrong. Her changed appearance alienates her from her old friends and makes it impossible to connect to new ones, for how can she tell people who know her as "Jesse" her birth sex? Hardest of all, Theresa cannot be with the hormonally-altered Jess because if Jess passes for male, it would force Theresa to pass as straight, forcing them both into a world of secrecy and isolation.

It is only when she meets Ruth that Jess sees a successful transgender life—"successful" meaning self-acceptance, for which there is no magic formula except itself. Ruth sees that no one has to be "night" or "day" and that in-between contains a world of possibilities.

At novel's end, Jess knows it is her difference and everything that came with it, good and bad that has made her the strong individual she is today.

Work

When Jess gets her first job at age fifteen, setting type by hand in a print shop, she enters a world where, for the first time, she can wear jeans and a T-shirt and not feel white-hot judgment around her. It is the beginning of her relationship to work, which frees her in important ways.

In the mid-1960s, it was easy for someone with just a high school diploma, or even a high school dropout like Jess, to find a job in industry that provided at least enough income for food and modest shelter. All you needed was a pair of hands and a high tolerance for repetition.

In Jess's circle of friends, work is more than a means to earn money (though that is its primary role). Work gives them the independence to live apart from feminine stereotypes. They do the jobs that men usually do—packing, machinery, shoveling, etc. Some of their male co-workers will jeer and sometimes try to sabotage them, but this is just another test of their strength.

The prize for blue-collar workers was to work union. The union protected workers from unfair dismissal and fought for above-decent wages. A butch who worked in a union factory could be the breadwinner for herself and her femme. It is no wonder that union workers hold fast to their hard-won rights and woe to the "scabs" (replacement workers) who dare to cross the picket line at strikes. An even bigger dream is to work in the steel or auto industries. When her butch friend, Grant, informs Jess that the steel plant is hiring fifty women, Jess seizes that opportunity, even though the cost is her steady job at the bindery. As she says to Duffy, the chief shop steward at the bindery, "You can ride a Honda and work at a bindery or you can ride a Harley and work at the steel plant" (Chapter 9, page 100).

Outside of a union, Jess often finds herself working two or more jobs at a time, sometimes on the night shift. It's a brutal schedule, but for her, it's necessary for survival. The slow decline of America's manufacturing sector begins in the 1970s. Those who made their living with their hands had to grab every opportunity they could with both hands, or they would end up on the streets.

A glancing look at Jess's resume would reveal a long list of jobs that are unglamorous and disrespected by general culture. To walk her employment road today would mean subsistence wages (with more than a little luck), little chance of pensions or benefits, and far less chance of union membership. But think of this: how welcome would a transgender person be in a white-collar office? Or in the military? Or on the floor of a retail store?

Gender

Stone Butch Blues is a story of the flexibility of gender, as opposed to sex. We are born as one of the two sexes, male or female (except for the very few who are intersex, both with both male and female genitalia). Gender, however—whether we express masculinity or femininity or alternate between the two—is not necessarily linked to biological sex.

Jess Goldberg was born a female. She has a masculine look, though, so much so that many question her sex from childhood on. Acting like a traditional female—wearing dresses, acting sweet and helpless—is a violation of her nature. When Jess wears a sports coat and tie, she is most herself. In the working-class lesbian terrain of 1960s Buffalo, she falls firmly in the category of butch. As a butch, Jess pursues femmes (feminine-acting lesbians) as sexual partners.

In the late 1960s, the new feminism looked back on defined gender roles and called them oppressive, in both the straight and the gay worlds. College-educated lesbians thought that butches were no better than leering, arrogant male chauvinists and femmes were their brainwashed playthings, and they didn't hesitate to say so. As happens all too often, the new paradigm sweeps away the old rules and then writes a new list of rules that is just as stifling.

Stone Butch Blues is not a critique on masculinity and femininity per se—as long as they arise from an individual's true self. When gender is imposed from the outside, whether it's from parents who want their daughter to be "normal" or feminists who want everyone to present an "equal," gender-neutral identity, it's a form of personal oppression. The best society is where people can express their gender(s) without shame or ridicule. We haven't gotten there yet.

Publication history

The novel was published by FireBrand Press in 1993. It was picked up by Alyson Books in 2003. In early 2013, Feinberg announced on hir Tumblr page that the book would be permanently out of print, but made to order copies would be available by request on hir website. Additionally, free PDFs of the text would be available in May 2013.

References

- ↑ Moses, Cat (1999). "Queering Class: Leslie Feinberg's Stone Butch Blues". Studies in the Novel 31.