Stochastic measurement procedure

A measurement is used to determine the actual value of a characteristic that is usually called measurand. A measurement is possible only if the measurand had been quantified prior to measurement by means of a suitable unit so that each value of the measurand is represented by a unique real number. For example, the characteristic "length" of a material object is quantified by the unit "meter", or the characteristic "(time) duration" of a development is quantified by the unit "second". Any measurement assumes a measurement process which is subject to randomness resulting in uncertainty about its indeterminate future outcome. Because of this uncertainty with respect to the future outcome of the measurement process, it is generally impossible to determine the true value of the measurand.

The related problems are addressed in the ISO Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement[1] (GUM) which was first published in 1993. However, since the GUM was published, complaints and critiques about it did not cease.[2] The weaknesses of the GUM were one reason that stochastic measurement procedures[3] were introduced in 2001. They are based on a rigorous introduction of the concepts of randomness and uncertainty

Measurement procedure

The measurand is given by a variable with fixed, i.e., determinate, but unknown value, and it is therefore called deterministic variable. A measurement itself is performed by a measurement device that defines a measurement process. In contrast to the measurand the measurement process is subject to randomness and its future outcome is therefore indeterminate. Consequently, the measurement process is represented by a variable X which is called a random variable.

The task is to conclude the unknown value of the measurand from the observed outcome of the measurement process. It is impossible to determine the true value of the measurand by means of the measurement process because of randomness. It is only possible to specify a set of values that includes the true value. Such a set constitutes the measurement result and it is called "correct" if it contains the true value of the measurand and wrong if not.

A measurement procedure is specified by the measurand given by the deterministic variable D, a measurement device that defines the admitted measurement range denoted  and the measurement process represented by the random variable X, and finally the measurement function

and the measurement process represented by the random variable X, and finally the measurement function  which assigns to each observation

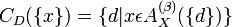

which assigns to each observation  with respect to the random variable X an measurement result

with respect to the random variable X an measurement result  .[4]

.[4]

Reliability of a measurement procedure

The symbol  is called reliability level of the stochastic measurement procedure and specifies a lower bound of the probability of obtaining a correct result when applying the measurement procedure. The larger the required reliability level

is called reliability level of the stochastic measurement procedure and specifies a lower bound of the probability of obtaining a correct result when applying the measurement procedure. The larger the required reliability level  the larger are the sets

the larger are the sets  that constitutes the possible measurement results.

that constitutes the possible measurement results.

How to select the reliability level  depends on the consequence of wrong measurement results. For measurement in safety related areas high values of

depends on the consequence of wrong measurement results. For measurement in safety related areas high values of  up to

up to  may be necessary, but if the consequences of wrong results are less serious, smaller values of

may be necessary, but if the consequences of wrong results are less serious, smaller values of  may be justified.

may be justified.

Accuracy of a measurement procedure

In traditional metrology, "measurement precision" and "measurement accuracy" are distinguished, this somewhat confusing differentiation is not necessary for stochastic measurement procedures, since they distinguish between correct and wrong measurement results and meet a reliability specification given by the reliability level  . The accuracy of a stochastic measurement procedure is defined by the average size of the measurement results, i.e., by the average size of the sets

. The accuracy of a stochastic measurement procedure is defined by the average size of the measurement results, i.e., by the average size of the sets  for all possible observations

for all possible observations  .

.

Measurement procedure and prediction procedure

Any stochastic measurement procedure is based on a stochastic model of the measurement process. This stochastic model is called Bernoulli space and enables the development of reliable and accurate stochastic prediction procedures given by the function  with the domain being the possible values of the measurand $D$ where the reliability level

with the domain being the possible values of the measurand $D$ where the reliability level  is a lower bound for the probability that an obtained prediction will actually occur.[5]

is a lower bound for the probability that an obtained prediction will actually occur.[5]

The measurement function  can be reduced to the prediction function

can be reduced to the prediction function  as given below:

as given below:

From this relation it is seen, that the measurement result  consists of those values d of the measurand D for which the observed outcome

consists of those values d of the measurand D for which the observed outcome  had been predicted.

had been predicted.

The prediction procedure to be derived based on the Bernoulli space  of the measurement process must meet the following three requirements:

of the measurement process must meet the following three requirements:

- The prediction procedure

must meet the reliability requirement given by the reliability level

must meet the reliability requirement given by the reliability level  .

. - The predictions

for

for  must cover all possible observations

must cover all possible observations .

. - The predictions

must be determined in a way that on average the measurement results have a minimum size.

must be determined in a way that on average the measurement results have a minimum size.

See also

References

- ↑ Guide to expression of uncertainty in measurement, .

- ↑ Elart von Collani, A critical note on the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM), Economic Quality Control, Vol. 23, 123−149, 2008.

- ↑ Elart von Collani and Monica Dumitrescu, Complete Neyman measurement procedures, Metrika, Vol. 54, 111−139, 2001.

- ↑ Elart von Collani, The Neyman theory − a scienfific measurement theory, in: V.P. Bulatov, I.G. Friedlaender (eds.): Basic Problems of Precision Theory, Nauka, St. Petersburg, pp. 74−94, 2001 (in Russian).

- ↑ Elart von Collani and Dmitri Stübner, Defining of reliability and precision of measurements, in: V.P. Bulatov (ed.), ``Problems of Mechanical Engineering: Precision, Friction and Depreciation, Nauka, St. Petersburg, 290−317, 2005 (in Russian).

External links

- Stochastikon Ecyclopedia,

- E-Learning Programme Stochastikon Magister,

- Homepage of Stochastikon GmbH,

- Economic Quality Control,

- Journal of Uncertain Systems,