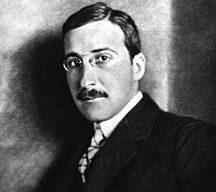

Stefan Zweig

| Stefan Zweig | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

November 28, 1881 Vienna, Austria-Hungary |

| Died |

February 22, 1942 (aged 60) Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, journalist and biographer |

| Known for | The Royal Game, Amok, Letter from an Unknown Woman, Confusion |

| Spouse(s) |

Friderike Maria von Winternitz (born Burger) (1920–1938; divorced) Lotte Altmann (1939–1942; his death) |

| Parent(s) |

Moritz Zweig (1845–1926) Ida Brettauer (1854–1938) |

| Relatives |

Alfred Zweig (1879–1977) (brother) |

| Signature |

|

Stefan Zweig (/zwaɪɡ, swaɪɡ/;[1] German: [tsvaɪk]; November 28, 1881 – February 22, 1942) was an Austrian novelist, playwright, journalist and biographer. At the height of his literary career, in the 1920s and 1930s, he was one of the most popular writers in the world.[2]

Biography

Zweig was born in Vienna, the son of Moritz Zweig (1845–1926), a wealthy Jewish textile manufacturer, and Ida Brettauer (1854–1938), a daughter of a Jewish banking family.[3] He was related to the Czech writer Egon Hostovský, who described him as "a very distant relative";[4] some sources describe them as cousins.

Zweig studied philosophy at the University of Vienna and in 1904 earned a doctoral degree with a thesis on "The Philosophy of Hippolyte Taine". Religion did not play a central role in his education. "My mother and father were Jewish only through accident of birth," Zweig said later in an interview. Yet he did not renounce his Jewish faith and wrote repeatedly on Jews and Jewish themes, as in his story Buchmendel. Zweig had a warm relationship with Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, whom he met when Herzl was still literary editor of the Neue Freie Presse, then Vienna's main newspaper; Herzl accepted for publication some of Zweig's early essays.[5] Zweig believed in internationalism and in Europeanism, as The World of Yesterday, his autobiography, makes clear. According to Amos Elon, Zweig called Herzl's book Der Judenstaat an "obtuse text, [a] piece of nonsense".[6]

At the beginning of World War I, patriotic sentiment was widespread, and extended to many German and Austrian Jews: Zweig, as well as Martin Buber and Hermann Cohen, all showed support.[7] Zweig served in the Archives of the Ministry of War and adopted a pacifist stand like his friend Romain Rolland, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature 1915. Zweig married Friderike Maria von Winternitz (born Burger) in 1920; they divorced in 1938. As Friderike Zweig she published a book on her former husband after his death.[8] She later also published a picture book on Zweig.[9] In 1939, Zweig married his secretary Lotte Altmann. Zweig's secretary in Salzburg from November 1919 to March 1938 was Anna Meingast (13 May 1881, Vienna – 17 November 1953, Salzburg).[10]

In 1934, following Hitler's rise to power in Germany, Zweig left Austria. He lived in England (in London first, then from 1939 in Bath). Because of the swift advance of Hitler's troops westwards, Zweig and his second wife crossed the Atlantic Ocean and travelled to the United States, where they settled in 1940 in New York City, and travelled. On August 22, 1940, they moved again to Petrópolis, a German-colonized mountain town 68 kilometers north of Rio de Janeiro known for historical reasons as Brazil's Imperial city.[11] Feeling more and more depressed by the growth of intolerance, authoritarianism, and Nazism, and feeling hopeless for the future for humanity, Zweig wrote a note about his feelings of desperation. Then, in February 23, 1942, the Zweigs were found dead of a barbiturate overdose in their house in the city of Petrópolis, holding hands.[12][13] He had been despairing at the future of Europe and its culture. "I think it better to conclude in good time and in erect bearing a life in which intellectual labour meant the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on Earth," he wrote.

The Zweigs' house in Brazil was later turned into a cultural centre and is now known as Casa Stefan Zweig.

Work

Zweig was a prominent writer in the 1920s and 1930s, befriending Arthur Schnitzler and Sigmund Freud.[14] He was extremely popular in the United States, South America and Europe, and remains so in continental Europe;[2] however, he was largely ignored by the British public.[15] His fame in America had diminished until the 1990s, when there began an effort on the part of several publishers (notably Pushkin Press, Hesperus Press, and The New York Review of Books) to get Zweig back into print in English.[16] Plunkett Lake Press Ebooks began to publish electronic versions of his non-fiction works. Since that time there has been a marked resurgence and a number of Zweig's books are back in print.[17]

Critical opinion of his oeuvre is strongly divided between those who despise his literary style as poor, lightweight and superficial,[15] and those who praise his humanism, simplicity and effective style.[16][18] Michael Hofmann is scathingly dismissive of Zweig's work, which he dubbed a "vermicular dither", adding that "Zweig just tastes fake. He's the Pepsi of Austrian writing." Even the author's suicide note left Hofmann gripped by "the irritable rise of boredom halfway through it, and the sense that he doesn't mean it, his heart isn't in it (not even in his suicide)".[19]

Zweig is best known for his novellas (notably The Royal Game, Amok, and Letter from an Unknown Woman – which was filmed in 1948 by Max Ophüls), novels (Beware of Pity, Confusion of Feelings, and the posthumously published The Post Office Girl) and biographies (notably Erasmus of Rotterdam, Conqueror of the Seas: The Story of Magellan, and Mary, Queen of Scotland and the Isles and also posthumously published, Balzac). At one time his works were published without his consent in English under the pseudonym "Stephen Branch" (a translation of his real name) when anti-German sentiment was running high. His biography of Queen Marie-Antoinette was later adapted as a Hollywood movie, starring the actress Norma Shearer in the title role.

Zweig's autobiography, The World of Yesterday, was completed in 1942 on the day before he committed suicide. It has been widely discussed as a record of "what it meant to be alive between 1881 and 1942" in central Europe; the book has attracted both critical praise[16] and hostile dismissal.[19]

Zweig enjoyed a close association with Richard Strauss, and provided the libretto for Die schweigsame Frau (The Silent Woman). Strauss famously defied the Nazi regime by refusing to sanction the removal of Zweig's name from the programme [20] for the work's première on June 24, 1935 in Dresden. As a result, Goebbels refused to attend as planned, and the opera was banned after three performances. Zweig later collaborated with Joseph Gregor, to provide Strauss with the libretto for one other opera, Daphne, in 1937. At least[21] one other work by Zweig received a musical setting: the pianist and composer Henry Jolles, who like Zweig had fled to Brazil to escape the Nazis, composed a song, "Último poema de Stefan Zweig",[22] based on "Letztes Gedicht", which Zweig wrote on the occasion of his 60th birthday in November 1941.[23] During his stay in Brazil, Zweig wrote Brasilien, Ein Land der Zukunft (Brazil, Land of the Future) which was an accurate analysis of his newly adopted country; in this book he managed to demonstrate a fair understanding of the Brazilian culture that surrounded him.

Zweig was a passionate collector of manuscripts. There are important Zweig collections at the British Library and at the State University of New York at Fredonia. The British Library's Stefan Zweig Collection was donated to the library by his heirs in May 1986. It specialises in autograph music manuscripts, including works by Bach, Haydn, Wagner, and Mahler. It has been described as "one of the world's greatest collections of autograph manuscripts".[24] One particularly precious item is Mozart's "Verzeichnüß aller meiner Werke"[25] – that is, the composer's own handwritten thematic catalogue of his works.

The 1993–1994 academic year at the College of Europe was named in his honour.

Bibliography

The dates mentioned below are the dates of first publication in German.

Fiction

- Forgotten Dreams, 1900 (Original title: Vergessene Träume)

- Spring in the Prater, 1900 (Original title: Praterfrühling)

- A Loser, 1901 (Original title: Ein Verbummelter)

- In the Snow, 1901 (Original title: Im Schnee)

- Two Lonely Souls, 1901 (Original title: Zwei Einsame)

- The Miracles of Life, 1903 (Original title: Die Wunder des Lebens)

- The Love of Erika Ewald, 1904 (Original title: Die Liebe der Erika Ewald)

- The Star Over the Forest, 1904 (Original title: Der Stern über dem Walde)

- The Fowler Snared, 1906 (Original title: Sommernovellette)

- The Governess, 1907 (Original title: Die Governante)

- Scarlet Fever, 1908 (Original title: Scharlach)

- Twilight, 1910 (Original title: Geschichte eines Unterganges)

- A Story Told In Twilight, 1911 (Original title: Geschichte in der Dämmerung)

- Burning Secret, 1913 (Original title: Brennendes Geheimnis )

- Fear, 1920 (Original title: Angst)

- Compulsion, 1920 (Original title: Der Zwang)

- The Eyes of My Brother, Forever, 1922 (Original title: Die Augen des ewigen Bruders)

- Fantastic Night, 1922 (Original title: Phantastische Nacht)

- Letter from an Unknown Woman, 1922 (Original title: Brief einer Unbekannten)

- Moonbeam Alley, 1922 (Original title: Die Mondscheingasse)

- Amok, 1922 (Original title: Amok) – novella, initially published with several others in Amok. Novellen einer Leidenschaft

- The Invisible Collection, 1925 (Original title: Die unsichtbare Sammlung)

- Downfall of the Heart, 1927 (Original title: Untergang eines Herzens")

- The Invisible Collection see Collected Stories below, (Original title: Die Unsichtbare Sammlung, first published in book form in 'Insel-Almanach auf das Jahr 1927'[26])

- The Refugee, 1927 (Original title: Der Flüchtling. Episode vom Genfer See).

- Confusion of Feelings or Confusion: The Private Papers of Privy Councillor R. Von D, 1927 (Original title: Verwirrung der Gefühle) – novella initially published in the volume Verwirrung der Gefühle: Drei Novellen

- Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman, 1927 (Original title: Vierundzwanzig Stunden aus dem Leben einer Frau) – novella initially published in the volume Verwirrung der Gefühle: Drei Novellen

- Buchmendel, 1929 (Original title: Buchmendel)

- Short stories, 1930 (Original title: Kleine Chronik. Vier Erzählungen) – includes Buchmendel

- Did He Do It?, published between 1935 and 1940 (Original title: War er es?)

- Leporella, 1935 (Original title: Leporella)

- Collected Stories, 1936 (Original title: Gesammelte Erzählungen) – two volumes of short stories:

1. The Chains (Original title: Die Kette)

2. Kaleidoscope (Original title: Kaleidoskop). Includes: Casual Knowledge of a Craft, Leporella, Fear, Burning Secret, Summer Novella, The Governess, Buchmendel, The Refugee, The Invisible Collection, Fantastic Night and Moonbeam Alley - Incident on Lake Geneva, 1936 (Original title: Episode an Genfer See Revised version of "Der Flüchtung. Episode vom Genfer See" published in 1927)

- The Buried Candelabrum, 1936

- Beware of Pity, 1939 (Original title: Ungeduld des Herzens) novel

- The Royal Game or Chess Story or Chess (Original title: Schachnovelle; Buenos Aires, 1942) – novella written in 1938–41,

- Journey into the Past, 1976 (Original title: Widerstand der Wirklichkeit)

- Clarissa, 1981 unfinished novel

- The Debt Paid Late, 1982 (Original title: Die spät bezahlte Schuld)

- The Post Office Girl, 1982 (Original title: Rausch der Verwandlung. Roman aus dem Nachlaß; The Intoxication of Metamorphosis)

Biographies and historical texts

- Béatrice Gonzalés-Vangell, Kaddish et Renaissance, La Shoah dans les romans viennois de Schindel, Menasse et Rabinovici, Septentrion, Valenciennes, 2005, 348 pages.

- Emile Verhaeren, 1910

- Three Masters: Balzac, Dickens, Dostoeffsky, 1920 (Original title: Drei Meister. Balzac – Dickens – Dostojewski. Translated into English by Eden and Cedar Paul and published in 1930 as Three Masters)

- Romain Rolland. The Man and His Works, 1921 (Original title: Romain Rolland. Der Mann und das Werk)

- Nietzsche, 1925 (Originally published in the volume titled: Der Kampf mit dem Dämon. Hölderlin – Kleist – Nietzsche)

- Decisive Moments in History, 1927 (Original title: Sternstunden der Menschheit. Translated into English and published in 1940 as The Tide of Fortune: Twelve Historical Miniatures[27])

- Adepts in Self-Portraiture: Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy, 1928 (Original title: Drei Dichter ihres Lebens. Casanova – Stendhal – Tolstoi)

- Joseph Fouché, 1929 (Original title: Joseph Fouché. Bildnis eines politischen Menschen) Now available as an electronic book

- Mental Healers: Franz Mesmer, Mary Baker Eddy, Sigmund Freud, 1932 (Original title: Die Heilung durch den Geist. Mesmer, Mary Baker-Eddy, Freud) Now available as an electronic book.

- Marie Antoinette: The Portrait of an Average Woman, 1932 (Original title: Marie Antoinette. Bildnis eines mittleren Charakters) ISBN 4-87187-855-4

- Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1934 (Original title: Triumph und Tragik des Erasmus von Rotterdam)

- Maria Stuart ISBN 4-87187-858-9

- The Right to Heresy: Castellio against Calvin, 1936 (Original title: Castellio gegen Calvin oder Ein Gewissen gegen die Gewalt)

- Conqueror of the Seas: The Story of Magellan, 1938 (Original title: Magellan. Der Mann und seine Tat) ISBN 4-87187-856-2

- Amerigo, 1942 (Original title: Amerigo. Geschichte eines historischen Irrtums) – written in 1942, published the day before he died ISBN 4-87187-857-0

- Balzac, 1946 – written, as Richard Friedenthal describes in a postscript, by Zweig in the Brazilian summer capital of Petrópolis, without access to the files, notebooks, lists, tables, editions and monographs that Zweig accumulated for many years and that he took with him to Bath, but that he left behind when he went to America. Friedenthal wrote that Balzac "was to be his magnum opus, and he had been working at it for ten years. It was to be a summing up of his own experience as an author and of what life had taught him." Friedenthal claimed that "The book had been finished", though not every chapter was complete; he used a working copy of the manuscript Zweig left behind him to apply "the finishing touches", and Friedenthal rewrote the final chapters (Balzac, translated by William and Dorothy Rose [New York: Viking, 1946], pp. 399, 402).

Plays

- Tersites, 1907 (Original title: Tersites)

- Das Haus am Meer, 1912

- Jeremiah, 1917 (Original title: Jeremias)

Other

- The World of Yesterday (Original title: Die Welt von Gestern; Stockholm, 1942) – autobiography

- Brazil, Land of the Future (Original title: Brasilien. Ein Land der Zukunft; Bermann-Fischer, Stockholm 1941)

- Journeys (Original title: Auf Reisen; Zurich, 1976); collection of essays

Letters

- Darién J. Davis; Oliver Marshall, eds. (2010). Stefan and Lotte Zweig's South American Letters: New York, Argentina and Brazil, 1940–42. New York: Continuum. ISBN 1441107126.

Adaptations

Artist Jeff Gabel created an English-language adaptation of Vierundzwanzig Stunden aus dem Leben einer Frau in a large-scale comic book format in 2004, titled 24 Hours in the Life of a Woman.

An adaptation by Stephen Wyatt of Beware of Pity was broadcast by BBC Radio 4 in 2011.[28]

The 2013 French film A Promise (Une promesse) is based on Zweig's novella Journey into the Past (Reise in die Vergangenheit).

The 2013 Swiss film Mary Queen of Scots directed by Thomas Imbach is based on Zweig's Maria Stuart.[29]

The end-credits for Wes Anderson's 2014 film The Grand Budapest Hotel say that the film was inspired in part by Zweig's novels. Anderson said that he had "stolen" from Zweig's novels Beware of Pity and The Post-Office Girl in writing the film, and it features actors Tom Wilkinson as The Author, a character based loosely on Zweig, and Jude Law as his younger, idealised self seen in flashbacks. Anderson also said that the film's protagonist, the concierge Gustave H., played by Ralph Fiennes, was based on Zweig. In the film's opening sequence, a teenaged girl visits a shrine for The Author, which includes a bust of him wearing Zweig-like spectacles and celebrated as his country's "National Treasure".[30]

See also

- Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century, a list which includes Confusion of Feelings

References

- ↑ "Zweig". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Stefan Zweig: The Secret Superstar" by Julie Kavanagh, Intelligent Life, (northern) spring 2009

- ↑ Prof.Dr. Klaus Lohrmann "Jüdisches Wien. Kultur-Karte" (2003), Mosse-Berlin Mitte gGmbH (Verlag Jüdische Presse)

- ↑ Egon Hostovský: Vzpomínky, studie a dokumenty o jeho díle a osudu, Sixty-Eight Publishers, 1974

- ↑ Meet the Austrian-Jewish novelist who inspired Wes Anderson's 'The Grand Budapest Hotel'

- ↑ Elon, Amos (2002). The Pity of it All. New York: Metropolitan Books. p. 287.

- ↑ Elon, 320

- ↑ Zweig, Friderike (1948). Stefan Zweig – Wie ich ihn erlebte. Berlin: F.A. Herbig Verlag.

- ↑ Zweig, Friderike (1961). Stefan Zweig : Eine Bildbiographie. München: Kindler.

- ↑ Werner Thuswaldner (December 14, 2000). "Wichtiges zu Stefan Zweig: Das Salzburger Literaturarchiv erhielt eine bedeutende Schenkung von Wilhelm Meingast". Salzburger Nachrichten. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- ↑ Júlia Dias Carneiro (April 30, 2009). "Revivendo o país do futuro de Stefan Zweig". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Stefan Zweig, Wife End Lives In Brazil". The United Press in The New York Times. February 23, 1942. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

Stefan Zweig, Wife End Lives In Brazil; Austrian-Born Author Left a Note Saying He Lacked the Strength to Go on – Author and Wife Die in Compact: Zweig and Wife Commit Suicide

- ↑ "Died". Time. March 2, 1942. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

Died. Stefan Zweig, 60, Austrian-born novelist, biographer, essayist (Amok, Adepts in Self-Portraiture, Marie Antoinette), and his wife, Elizabeth; by poison; in Petropolis, Brazil. Born into a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna, Zweig turned from casual globe-trotting to literature after World War I, wrote prolifically, smoothly, successfully in many forms. His books banned by the Nazis, he fled to Britain in 1938 with the arrival of German troops, became a British subject in 1940, moved to the U.S. the same year, to Brazil the next. He was never outspoken against Naziism, believed artists and writers should be independent of politics. Friends in Brazil said he left a suicide note explaining that he was old, a man without a country, too weary to begin a new life. His last book: Brazil: Land of the Future.

- ↑ Fowles, John (1981). Introduction to "The Royal Game". New York: Obelisk. pp. ix.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Walton, Stuart (March 26, 2010). "Stefan Zweig? Just a pedestrian stylist". The Guardian (London).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Lezard, Nicholas (December 5, 2009). "The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ↑ Rohter, Larry. "Stefan Zweig, Austrian Novelist, Rises Again". New York Times. 28 May 2014

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Stefan Zweig". Author's Calendar. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Hofmann, Michael (2010). "Vermicular Dither". London Review of Books 32 (2): 9–12. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Richard Strauss/Stefan Zweig: BriefWechsel, 1957, translated as A Confidential Matter, 1977

- ↑ "Stefan Zweig". REC Music Foundation. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- ↑ Musica Reanimata of Berlin, Henry Jolles accessed January 25, 2009

- ↑ Biographical sketch of Stefan Zweig at Casa Stefan Zweig accessed September 28, 2008

- ↑ The Zweig Music Collection at the British Library

- ↑ Mozart's "Verzeichnüß aller meiner Werke" at the British Library Online Gallery accessed October 14, 2009

- ↑ "Die unsichtbare sammlung". Open Library. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- ↑ "Stefan Zweig." The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Encyclopedia.com. 21 November 2010.

- ↑ "'Classic Serial: Stefan Zweig – Beware of Pity'". Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ↑ Mary Queen of Scots (2013) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "'I stole from Stefan Zweig': Wes Anderson on the author who inspired his latest movie". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

Further reading

- Elizabeth Allday, Stefan Zweig: A Critical Biography, J. Philip O'Hara, Inc., Chicago, 1972

- Darién J. Davis; Oliver Marshall, eds. (2010). Stefan and Lotte Zweig's South American Letters: New York, Argentina and Brazil, 1940–42. New York: Continuum. ISBN 1441107126.

- Alberto Dines, Morte no Paraíso, a Tragédia de Stefan Zweig, Editora Nova Fronteira 1981, (rev. ed.) Editora Rocco 2004

- Alberto Dines, Tod im Paradies. Die Tragödie des Stefan Zweig, Edition Büchergilde, 2006

- Randolph J. Klawiter, Stefan Zweig. An International Bibliography, Ariadne Press, Riverside, 1991

- Donald A. Prater, European of Yesterday: A Biography of Stefan Zweig, Holes and Meier Publ., (rev. ed.) 2003

- George Prochnik, The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World, Random House, 2014, ISBN 978-1590516126

- Marion Sonnenfeld (editor), The World of Yesterday's Humanist Today. Proceedings of the Stafan Zweig Symposium, texts by Alberto Dines, Randolph J. Klawiter, Leo Spitzer and Harry Zohn, State University of New York Press, 1983

- * Vanwesenbeeck, Birger; Gelber, Mark H. Stefan Zweig and World Literature: Twenty-First-Century Perspectives. Rochester: Camden House. ISBN 9781571139245.

- Friderike Zweig, Stefan Zweig, Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1946 (An account of his life by his first wife)

- Martin Mauthner, German Writers in French Exile, 1933–1940, Vallentine Mitchell, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-85303-540-4

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Stefan Zweig |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stefan Zweig. |

- Zweig Music Collection at the British Library

- Stefan Zweig Collection at the Daniel A. Reed Library, State University of New York at Fredonia, Fredonia, NY

- Stefan Zweig Online Bibliography, a wiki hosted by Daniel A. Reed Library, State University of New York at Fredonia, Fredonia, NY

- StefanZweig.org

- StefanZweig.de

- Stefan Zweig Centre Salzburg

- Works by Stefan Zweig at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Stefan Zweig at Internet Archive

- Works by Stefan Zweig at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Beware of Pity, review by Joan Acocella in The New York Review of Books, July 13, 2006

- "No Exit", article on Zweig at Tablet Magazine

- Zweig's foreword to The World of Yesterday

- Stefan Zweig at perlentaucher.de – das Kulturmagazin (German)

|