Steel strike of 1919

| Date | September 21, 1919 – January 8, 1920 |

|---|---|

| Outcome | Strike collapsed |

The steel strike of 1919 was an attempt by the weakened Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers (the AA) to organize the United States steel industry in the wake of World War I. The strike began on September 21, 1919,[1][2] and collapsed on January 8, 1920.

The AA had formed in 1876. It was a union of skilled iron and steel workers which was deeply committed to craft unionism. However, technological advances had slashed the number of skilled workers in both industries.

Background

In 1892, the AA had lost a bitter strike at the Carnegie Steel Company's steel mill in Homestead, Pennsylvania. The Homestead Strike, which culminated with a day-long gun battle on July 6 that left 12 dead and dozens wounded, led to a wave of de-unionization. From a high of more than 24,000 members in 1892, union membership had sunk to less than 8,000 by 1900.

The union attempted to organize workers in the tin industry, but a sudden wave of industry consolidations left the union facing the gigantic U.S. Steel corporation. In the U.S. Steel Recognition Strike of 1901, the union struck the fledgling company and won nearly all its demands. But the union's executive board wanted more and rejected the pact. U.S. Steel was able to muster its resources and break the strike.

By the end of World War I, the AA was a shell of its former self.

Roots of the crisis

The American Federation of Labor (AFL) began organizing unskilled iron and steel workers into federal unions in 1901. Local groups of wire drawers, house men, tube workers, blast furnace men and others had all formed unions. The Federal Association of Wire Drawers was chartered in 1896, the Tin Plate Workers' Protective Association in 1899, the International Association of Blast Furnace Workers in 1901, and the International Association of Tube Workers in 1902. Most internationals disbanded after a short time, but many local federal unions became deeply entrenched in the workplace.[3]

Insistence on retaining its craft union identity kept it from establishing a stronger presence in the metals industries. The union was in crisis, however. The steel industry was growing quickly, and the skilled jobs in which AA members worked were disappearing. The union had to act in order to save itself. At the November 1909 AFL convention, AA president P.J. McArdle introduced a resolution, which quickly passed, calling for an organizing drive at U.S. Steel. By December, organizers were flooding plants throughout the Northeast and Midwest. But workers remained skittish after the failed 1901 strike, and the drive never got off the ground.[4]

The AFL then attempted to organize workers on the AA's behalf. The AFL's strategy was twofold. First, the federation would wait for a strong upturn in economic conditions. When workers felt less dependence on their employer and showed signs of restiveness, the organization would initiate an organizing effort. Second, the federation would create staff-driven unions run from national AFL headquarters. Samuel Gompers and other AFL leaders had a nativist view of the unskilled immigrants working in steel plants. Distrusting immigrant workers to manage their own affairs, the AFL intended to run unions for them.

These assumptions doomed the organizing drive. The AFL did not account for the hardening anti-union attitudes of U.S. Steel executives and plant managers, and the federation had no real plan to counterbalance the vast financial resources the company would pour into anti-union espionage, strikebreaking and union avoidance measures. When the AFL did organize a local union, the federation's patronizing attitudes and management style alienated workers and left the local union powerless.[5]

During World War I, the AA saw some limited growth. Inflation pushed restive employees to demand wage increases which the AFL and the AA were quick to claim credit for. But membership growth remained weak and scattered rather than substantive and strategic. To encourage more organizing, the AFL formed a National Committee for Organizing the Iron and Steel Workers. More than 15 AFL unions participated in the committee, while 24 claimed jurisdiction over portions of the steel industry. John Fitzpatrick and William Z. Foster of the Chicago Federation of Labor were the committee's leaders.

But the organizing drive was hampered by the refusal of many of the participating unions to provide resources and support, and by the committee's lack of a mechanism to enforce jurisdictional agreements and requisition funds. Although the National Committee had some initial success in establishing local steelworker councils, these councils never received formal recognition from the AFL or the AA.[6]

Strike

Shortly after Armistice Day, AFL organizers in and around Pittsburgh began to be harassed by the steel companies: permits for meetings were denied, meeting halls could not be rented (when they were, the local Board of Health closed the hall), Pinkerton agents stopped organizers at the train station and forced them to leave town, and literature was seized. The AFL sought assistance from its political allies, but the harassment continued. The anti-union pressure spread to the Midwest and West. As the post-war recession affected the economy, plant managers targeted union supporters and those with large families for dismissal in order to ensure that union efforts were stifled.[7]

The AFL pushed back. On April 1, 1919, thousands of miners in Pennsylvania went on strike to demand that local officials allow union meetings. Terrified town mayors soon issued the required permits. The mass meetings whipped up pro-union sentiment. Steelworkers felt betrayed by the broken promises of employers and the government to keep prices low, raise wages and improve working conditions.

The AFL held a national steelworkers' conference in Pittsburgh on May 25, 1919, to build momentum for an organizing drive but refused to let the workers strike. Disillusioned employees began to abandon the labor movement. The National Committee debated the strike issue through June and July. Worried committee members, seeing their chance for solid membership gains slipping away, agreed to a strike referendum in the mills in August. The response was 98% in favor of a general steelworker strike to begin on September 22, 1919.

As the strike deadline approached, the National Committee attempted to negotiate with U.S. Steel chairman Elbert Gary. The committee also asked for President Woodrow Wilson's help. Telegrams and letters were sent back and forth, but Gary refused to meet, and Wilson—on his ill-fated tour to drum up support for the League of Nations—was unable to influence the company.[8]

The steelworkers were forced to carry out their strike threat. The September strike shut down half the steel industry, including almost all mills in Pueblo, Colorado; Chicago, Illinois, Wheeling, West Virginia; Johnstown, Pennsylvania; Cleveland, Ohio; Lackawanna, New York; and Youngstown, Ohio. The steel companies had seriously misjudged the strength of worker discontent.[9]

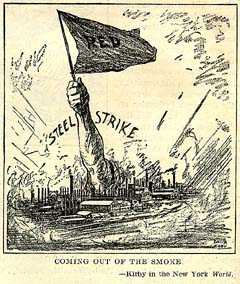

New York World

October 11, 1919

But the owners quickly turned public opinion against the AFL. The post-war Red Scare had swept the country in the wake of the Russian revolution of October 1917. The steel companies took eager advantage of the change in the political climate. As the strike began, they published information exposing National Committee co-chairman William Z. Foster's past as a Wobblie and syndicalist, and claimed this was evidence that the steelworker strike was being masterminded by communists and revolutionaries. The steel companies played on nativist fears by noting that a large number of steelworkers were immigrants. Public opinion quickly turned against the striking workers. Only Wilson's stroke on September 26, 1919, prevented government intervention, since Wilson's advisors were loath to take action with the president incapacitated.

The federal government's inaction permitted state and local authorities and the steel companies room to maneuver. Mass meetings were prohibited in most strike-stricken areas. Veterans and tradesmen were pressed into service as deputies. The Pennsylvania state police clubbed picketers, dragged strikers from their homes and jailed thousands on flimsy charges. In Delaware, company guards were deputized and threw 100 strikers in jail on fake weapons charges. In Monessen, Pennsylvania, hundreds of men were jailed then were promised release if they agreed to disavow the union and return to work. After strikebreakers and police clashed with unionists in Gary, Indiana, the U.S. Army took over the city on October 6, 1919, and martial law was declared. National guardsmen, leaving Gary after federal troops had taken over, turned their anger on strikers in nearby Indiana Harbor, Indiana.[10]

Steel companies also turned toward strikebreaking and rumor-mongering to demoralize the picketers. Between 30,000 and 40,000 unskilled African-American and Mexican American workers were brought to work in the mills. Company officials played on the racism of many white steelworkers by pointing out how well-fed and happy the black workers seemed now that they had 'white' jobs. Company spies also spread rumors that the strike had collapsed elsewhere, and they pointed to the operating steel mills as proof that the strike had been defeated.[11]

The AFL sabotaged the strike in several ways. When the AA demanded that the AFL contribute to strike relief, Gompers sarcastically asked how much money the AA intended to contribute. Few unions on either the National Committee or in the AFL contributed relief funds.

As October and November wore on, many AA members crossed the picket lines to return to work. AA affiliates collapsed because of the member infighting this caused. Unions on the National Committee, squabbling over jurisdiction in the steel mills, publicly accused one another of failing to support the strike.[12]

The Great Steel Strike of 1919 collapsed on January 8, 1920. The Chicago mills gave in at the end of October. By the end of November, workers were back at their jobs in Gary, Johnstown, Youngstown and Wheeling. The AA, ravaged by the strike and watching its locals collapse, argued with the National Committee for a unilateral return to work. But the National Committee voted to keep the strike going against the union's wishes.

The strike dragged on in isolated areas like Pueblo and Lackawanna, but the job action decimated the AA. AA president Michael F. Tighe demanded that the National Committee disband; his motion failed. Tighe withdrew from the National Committee. Absent the union with primary jurisdiction over the steel industry, the National Committee ceased operating.[13]

The steel strike of 1919 had been a complete rout for the American labor movement.

Impact

Almost no union organizing in the steel industry occurred in the next 15 years. Advances in technology, such as the development of the widestrip continuous sheet mill, made most of the skilled jobs in steelmaking obsolete.

When the AA considered calling a national strike in 1929 to demand that the new technology be rejected, nearly every AA affiliate returned its charter to the international rather than obey the strike order.

By 1930, the AA had only 8,600 members. Its leadership, burned by failed strikes in 1892, 1901 and 1919, turned accommodationist and submissive.[14]

The AA, which had only a minor role to play in the steel strike of 1919, remained moribund until the advent of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee in 1936.

Notes

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Brody, 1969, p. 130-132.

- ↑ Brody, 1969, p. 132-133.

- ↑ Brody, 1969, p. 140-45.

- ↑ Brody, 1969, p. 199-225; Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 219-20.

- ↑ Rayback, p. 285-286; Brody, 1969, p. 231-33.

- ↑ Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 220; Rayback, p. 286-87; Brody, 1969, p. 233-36.

- ↑ Brody, 1969, p. 233-44.

- ↑ Rayback, p. 287; Brody, 1969, p. 244-253; Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 220; .

- ↑ Rayback, p. 287; Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 220-21; Brody, 1969, p. 254-55.

- ↑ Brody, 1969, p. 255-58.

- ↑ Brody, 1969, p. 258–62.

- ↑ Brody, 1969, p. 277-78; Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 258.

References

| Library resources about Steel strike of 1919 |

- Brody, David. Steelworkers in America: The Nonunion Era. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1969. ISBN 0-252-06713-4

- Dubofsky, Melvyn and Dulles, Foster Rhea. Labor in America: A History. 6th ed. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, Inc., 1999. ISBN 0-88295-979-4

- Robert K. Murray. "Communism and the Great Steel Strike of 1919" The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 38, No. 3. (Dec., 1951), pp. 445–466. JSTOR

- Rayback, Joseph G. A History of American Labor. Rev. and exp. ed. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1966. ISBN 0-02-925850-2