State of Palestine

| State of Palestine[i] دولة فلسطين Dawlat Filasṭīn |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: "فدائي" "Fida'i"[1][2] "My Redemption" |

||||||

.svg.png) |

||||||

| ||||||

| Largest city | Jerusalem (claimed) Gaza City (de facto)a | |||||

| Official languages | Arabic | |||||

| Government | De jure parliamentary republic operating de facto as a semi-presidential republic[5] | |||||

| - | President | Mahmoud Abbasb | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Rami Hamdallah | ||||

| - | Speaker of Parliament | Salim Zanoun | ||||

| Legislature | National Council | |||||

| Formation | ||||||

| - | Declaration of Independence | 15 November 1988 | ||||

| - | UNGA observer state resolution | 29 November 2012 | ||||

| - | Transformed from PA | 3 January 2013 | ||||

| - | Sovereignty dispute with Israel | Ongoingc[iii][6][7] | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 6,220 km2

2,400 sq mi |

||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2014 estimate | 4,550,368[10] (123rd) | ||||

| - | Density | 731/km2 1,895/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2008a estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $11.95 billiona (–) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $2,900a (–) | ||||

| Gini (2009) | 35.5[11] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2013) | medium · 107th |

|||||

| Currency |

|

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC+2) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | (UTC+3) | ||||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +970 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | PS | |||||

| Internet TLD | .ps | |||||

| a. | Population and economy statistics and rankings are based data of the PCBS. | |||||

| b. | Also the leader of the state's government.[iv] | |||||

| c. | The territories claimed are under Israeli occupation. | |||||

The State of Palestine[i] (Arabic: دولة فلسطين Dawlat Filasṭīn) is a de jure sovereign state in the Middle East.[14][15] Its independence was declared on 15 November 1988 by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in Algiers as a government-in-exile. The State of Palestine claims the West Bank and Gaza Strip,[16] and has designated Jerusalem as its capital,[ii][3][4] with partial control of those areas assumed in 1994 as the Palestinian Authority. Most of the areas claimed by the State of Palestine have been occupied by Israel since 1967 in the aftermath of the Six-Day War.[7] The State of Palestine applied for United Nations (UN) membership in 2011[16] but in 2012 was granted a non-member observer state status.[14][15]

The October 1974 Arab League summit designated the PLO as the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people" and reaffirmed "their right to establish an independent state of urgency."[17] In November 1974, the PLO was recognized as competent on all matters concerning the question of Palestine by the UN General Assembly granting them observer status as a "non-state entity" at the UN.[18][19] After the 1988 Declaration of Independence, the UN General Assembly officially "acknowledged" the proclamation and decided to use the designation "Palestine" instead of "Palestine Liberation Organization" in the UN.[20][21] In spite of this decision, the PLO did not participate at the UN in its capacity of the State of Palestine's government.[22]

In 1993, in the Oslo Accords, Israel acknowledged the PLO negotiating team as "representing the Palestinian people", in return for the PLO recognizing Israel's right to exist in peace, acceptance of UN Security Council resolutions 242 and 338, and its rejection of "violence and terrorism".[23] As a result, in 1994 the PLO established the Palestinian National Authority (PNA or PA) territorial administration, that exercises some governmental functions[iii] in parts of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.[24][25] In 2007, the Hamas takeover of Gaza Strip politically and territorially divided the Palestinians, with Abbas's Fatah left largely ruling the West Bank and recognized internationally as the official Palestinian Authority,[26] while Hamas has secured its control over the Gaza Strip. In April 2011, the Palestinian parties signed an agreement of reconciliation, but its implementation had stalled[26] until a unity government was formed on 2 June 2014.[27]

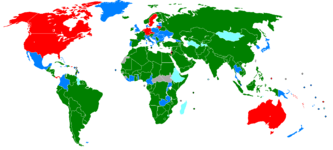

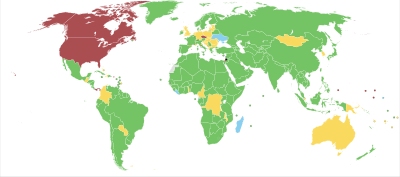

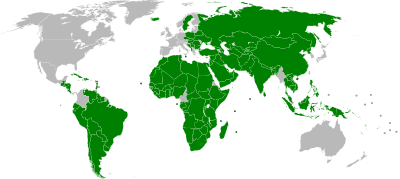

On 29 November 2012, in a 138–9 vote (with 41 abstentions and 5 absences),[28] the United Nations General Assembly passed resolution 67/19, upgrading Palestine from an "observer entity" to a "non-member observer state" within the United Nations system, which was described as recognition of the PLO's sovereignty.[14][15][29][30][31] Palestine's new status is equivalent to that of the Holy See.[32] The UN has permitted Palestine to title its representative office to the UN as "The Permanent Observer Mission of the State of Palestine to the United Nations",[33] and Palestine has instructed its diplomats to officially represent "The State of Palestine"—no longer the Palestinian National Authority.[31] On 17 December 2012, UN Chief of Protocol Yeocheol Yoon declared that "the designation of 'State of Palestine' shall be used by the Secretariat in all official United Nations documents",[34] thus recognising the title 'State of Palestine' as the state's official name for all UN purposes. As of 30 October 2014, 135 (69.9%) of the 193 member states of the United Nations have recognised the State of Palestine.[30][35] Many of the countries that do not recognise the State of Palestine nevertheless recognise the PLO as the "representative of the Palestinian people". The PLO's Executive Committee is empowered by the Palestinian National Council to perform the functions of government of the State of Palestine.[36] On 25 May 2014 during his visit to the Holy Land, Pope Francis, in a carefully worded statement, made explicit reference to the "State of Palestine".[37]

Etymology

Since the British Mandate, the term "Palestine" has been associated with the geographical area that currently covers the State of Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.[38] General use of the term "Palestine" or related terms to the area at the southeast corner of the Mediterranean Sea beside Syria has historically been taking place since the times of Ancient Greece, with Herodotus writing of a "district of Syria, called Palaistine" in which Phoenicians interacted with other maritime peoples in The Histories.[39]

Background

In 1946, Transjordan gained independence from the British Mandate for Palestine. A year later, the UN adopted a partition plan for a two-state solution in the remaining territory of the mandate. The plan was accepted by the Jewish leadership, but rejected by the Arab leaders and Britain refused to implement the plan. On the eve of final British withdrawal, the Jewish Agency for Israel declared the establishment of the State of Israel according to the proposed UN plan. The Arab Higher Committee did not declare a state of its own and instead, together with Transjordan, Egypt, and the other members of the Arab League of the time, commenced military action resulting in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. During the war, Israel gained additional territories that were expected to form part of the Arab state under the UN plan. Egypt occupied the Gaza Strip and Transjordan occupied the West Bank. Egypt initially supported the creation of an All-Palestine Government, but disbanded it in 1959. Transjordan never recognized it and instead decided to incorporate the West Bank with its own territory to form Jordan. The annexation was ratified in 1950 but was rejected by the international community. The Six-Day War in 1967, when Egypt, Jordan, and Syria fought against Israel, ended with Israel being in occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, besides other territories.

In 1964, when the West Bank was controlled by Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organization was established there with the goal to confront Israel. The Palestinian National Charter of the PLO defines the boundaries of Palestine as the whole remaining territory of the mandate, including Israel. Following the Six-Day War, the PLO moved to Jordan, but later relocated to Lebanon after Black September in 1971. In 1974, the Arab League recognised the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, and it gained observer status at the UN General Assembly. After the 1982 Lebanon War, the PLO moved to Tunisia.

In 1979, through the Camp David Accords, Egypt signaled an end to any claim of its own over the Gaza Strip. In July 1988, Jordan ceded its claims to the West Bank—with the exception of guardianship over Haram al-Sharif—to the PLO. In November 1988, the PLO legislature, while in exile, declared the establishment of the "State of Palestine". In the month following, it was quickly recognised by many states, including Egypt and Jordan. In the Palestinian Declaration of Independence, the State of Palestine is described as being established on the "Palestinian territory", without explicitly specifying further. Because of this, some of the countries that recognised the State of Palestine in their statements of recognition refer to the "1967 borders", thus recognizing as its territory only the occupied Palestinian territory, and not Israel. The UN membership application submitted by the State of Palestine also specified that it is based on the "1967 borders".[16] During the negotiations of the Oslo Accords, the PLO recognised Israel's right to exist, and Israel recognised the PLO as representative of the Palestinian people. Between 1993 and 1998, the PLO made commitments to change the provisions of its Palestinian National Charter that are inconsistent with the aim for a two-state solution and peaceful coexistence with Israel.

After Israel took control of the West Bank from Jordan and Gaza Strip from Egypt, it began to establish Israeli settlements there. These were organised into Judea and Samaria district (West Bank) and Hof Aza Regional Council (Gaza Strip) in the Southern District. Administration of the Arab population of these territories was performed by the Israeli Civil Administration of the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories and by local municipal councils present since before the Israeli takeover. In 1980, Israel decided to freeze elections for these councils and to establish instead Village Leagues, whose officials were under Israeli influence. Later this model became ineffective for both Israel and the Palestinians, and the Village Leagues began to break up, with the last being the Hebron League, dissolved in February 1988.[40]

As envisioned in the Oslo Accords, Israel allowed the PLO to establish interim administrative institutions in the Palestinian territories, which came in the form of the PNA. It was given civilian control in Area B and civilian and security control in Area A, and remained without involvement in Area C. In 2005, following the implementation of Israel's unilateral disengagement plan, the PNA gained full control of the Gaza Strip with the exception of its borders, airspace, and territorial waters.[iii] Following the inter-Palestinian conflict in 2006, Hamas took over control of the Gaza Strip (it already had majority in the PLC), and Fatah took control of the West Bank (and the rest of the PNA institutions). From 2007, the Gaza Strip was governed by Hamas, and the West Bank by Fatah.

McMahon–Hussein Correspondence (1915–16)

In the early years of World War I, negotiations took place between the British High Commissioner in Egypt Henry McMahon and Sharif of Mecca Husayn bin Ali for an alliance of sorts between the Allies and the Arabs in the Near East against the Ottomans. On 24 October 1915, McMahon sent to Hussein a note which the Arabs came to regard as their "Declaration of Independence". In McMahon's letter, part of the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence, McMahon declared Britain's willingness to recognise the independence of the Arabs, both in the Levant and the Hejaz, subject to certain exemptions. It stated on behalf of the Government of Great Britain that:

The two districts of Mersina and Alexandretta and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab, and should be excluded from the limits demanded.

With the above modification, and without prejudice of our existing treaties with Arab chiefs, we accept those limits.

As for those regions lying within those frontiers wherein Great Britain is free to act without detriment to the interest of her ally, France, I am empowered in the name of the Government of Great Britain to give the following assurances and make the following reply to your letter:

- Subject to the above modifications, Great Britain is prepared to recognize and support the independence of the Arabs in all the regions within the limits demanded by the Sherif of Mecca.[41]

The exemptions from Arab control of certain areas set out in the McMahon note were to seriously complicate the problems of peace in the Near East. At the time, the Arab portions of the Ottoman Empire were divided into administrative units called vilayets and sanjaks. Palestine was divided into the sanjuks of Acre and Nablus, both of which were a part of the vilayet of Beirut, and an independent sanjak of Jerusalem. The areas exempted from Arab control by the McMahon note included "Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo." The British understanding was that "Damascus" meant the vilayet and not the city of Damascus, and accordingly virtually all of Palestine was excluded from Arab control. The British entered into the secret Sykes–Picot Agreement on 16 May 1916 and the commitment of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, for example, on that understanding.

The Arabs, however, insisted at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference at the end of the war that "Damascus" meant the city of Damascus – which left Palestine in their hands.[42] However, in 1915, these problems of interpretation did not occur to Hussein, who agreed to the British wording. The Arab interpretation of the agreement formed the basis of Arab claims to Palestine at the peace conference.

League of Nations Mandate for Palestine (1920–1948)

Despite Arab objections based in part on the Arab interpretation of the McMahon correspondence noted above, Britain was given the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine. The Mandate was administered as two territories: Palestine and Transjordan,[43] with the Jordan River being the boundary between them. The boundaries under the Mandate also did not follow those sought by the Jewish community, which sought the inclusion of the east bank of the Jordan into the Palestinian territory, to which the objective of the Mandate for a homeland for the Jewish people would apply. It was made clear from before the commencement of the Mandate, and a clause to that effect was inserted in the Mandate, that the objective set out in the Mandate would not apply to Transjordan. Transjordan was destined for early independence. The objective of the Mandate was to apply only to territory west of the Jordan, which was commonly referred to as Palestine by the British administration, and as Eretz Israel by the Jewish community.

The Arab League and the Arab Higher Committee (1945)

The framers of the Arab League sought to include the Palestinian Arabs within the framework of the League from its inception.[44] An annex to the League Pact declared:[45]

Even though Palestine was not able to control her own destiny, it was on the basis of the recognition of her independence that the Covenant of the League of Nations determined a system of government for her. Her existence and her independence among the nations can, therefore, no more be questioned de jure than the independence of any of the other Arab States... Therefore, the States signatory to the Pact of the Arab League consider that in view of Palestine's special circumstances, the Council of the League should designate an Arab delegate from Palestine to participate in its work until this country enjoys actual independence.

In November 1945, the Arab League reconstituted the Arab Higher Committee comprising twelve members[46] as the supreme executive body of Palestinian Arabs in the territory of the British Mandate of Palestine. The committee was dominated by the Palestine Arab Party and was immediately recognised by Arab League countries. The Mandate government recognised the new Committee two months later. The Constitution of the League of Arab States says the existence and independence of Palestine cannot be questioned de jure even though the outward signs of this independence have remained veiled as a result of force majeure.[47]

1947–48 War in Palestine

Partition of Palestine (1948)

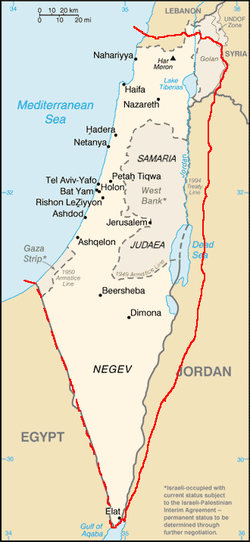

Boundaries defined in the 1947 UN Partition Plan for Palestine:

Armistice Demarcation Lines of 1949:

In 1946, Jewish leaders – including Nahum Goldmann, Rabbi Abba Silver, Moshe Shertok, and David Ben Gurion – proposed a union between Arab Palestine and Transjordan.[48] Also in 1946, leaders of the Zionist movement in the U.S. sought the postponement of a determination of the application by Transjordan for United Nations membership until the status of Mandate Palestine as a whole was determined.[49] However, at its final session the League of Nations recognized the independence of Transjordan, with the agreement of Britain.

The United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP), which was formed to recommend a solution to Britain's dilemma in Palestine, subsequently reported that the proposed Arab state would not be economically viable. The report indicated that the Arab state would be forced to call for financial assistance "from international institutions in the way of loans for expansion of education, public health and other vital social services of a non-self-supporting nature." A technical note from the Secretariat explained that without some redistribution of customs from the Jewish state, Arab Palestine would not be economically viable. The Committee was satisfied that the proposed Jewish State and the City of Jerusalem would be viable.[50]

In 1947, the United Nations proposed the partition of Mandate Palestine into an Arab state, a Jewish state, and a Corpus Separatum for Jerusalem. The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a resolution adopted on 29 November 1947 by the General Assembly of the United Nations. Its title was United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181 (II) Future Government of Palestine. The resolution noted Britain's planned termination of the British Mandate for Palestine and recommended the partition of Palestine into two states, one Arab and one Jewish, with the Jerusalem-Bethlehem area being under special international protection, administered by the United Nations. The resolution included a highly detailed description of the recommended boundaries for each proposed state.[51] The resolution also contained a plan for an economic union between the proposed states, and a plan for the protection of religious and minority rights. The resolution sought to address the conflicting objectives and claims to the Mandate territory of two competing nationalist movements, Zionism (Jewish nationalism) and Arab nationalism, as well as to resolve the plight of Jews displaced as a result of the Holocaust. The resolution called for the withdrawal of British forces and termination of the Mandate by 1 August 1948, and establishment of the new independent states by 1 October 1948.

The Partition Plan was accepted by the Jewish leadership, but rejected by the Arab leaders. The Arab League threatened to take military measures to prevent the partition of Palestine and to ensure the national rights of the Palestinian Arab population. On 14 May 1948, the chairman of the Jewish Agency for Palestine,[52] declared the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.[53] U.S. President Harry Truman recognised the State of Israel de facto the following day. The Arab countries declared war on the newly formed State of Israel heralding the start of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. On 12 April 1948, the Arab League announced:

The Arab armies shall enter Palestine to rescue it. His Majesty (King Farouk, representing the League) would like to make it clearly understood that such measures should be looked upon as temporary and devoid of any character of the occupation or partition of Palestine, and that after completion of its liberation, that country would be handed over to its owners to rule in the way they like.[54]

Arab–Israeli War (1948)

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Transjordan occupied the area of Cisjordan, now called the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), which it continued to control in accordance with the 1949 Armistice Agreements and a political union formed in December 1948. Military Proclamation Number 2 of 1948 provided for the application in the West Bank of laws that were applicable in Palestine on the eve of the termination of the Mandate. On 2 November 1948, the military rule was replaced by a civilian administration by virtue of the Law Amending Public Administration Law in Palestine. Military Proclamation Number 17 of 1949, Section 2, vested the King of Jordan with all the powers that were enjoyed by the King of England, his ministers and the High Commissioner of Palestine by the Palestine Order-in-Council, 1922. Section 5 of this law confirmed that all laws, regulations and orders that were applicable in Palestine until the termination of the Mandate would remain in force until repealed or amended.[55]

After the war, which the Israelis call the War of Independence and the Palestinians call the Catastrophe, the 1949 Armistice Agreements established the separation lines between the combatants, leaving Israel in control of some of the areas which had been designated for the Arab state under the Partition Plan, Transjordan in control of the West Bank, Egypt in control of the Gaza Strip and Syria in control of the Himmah Area. The Arab League "supervised" the Egyptian trusteeship of the Palestinian government in Gaza after and secured assurances from Jordan that the 1950 Act of Union was "without prejudice to the final settlement".[56][57]

The Second Arab-Palestinian Congress[58] was held in Jericho on 1 December 1948 at the end of the war. The delegates proclaimed Abdullah King of Palestine and called for a union of Arab Palestine with the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan.[59] Avi Plascov says that Abdullah contacted the Nashashibi opposition, local mayors, mukhars, those opposed to the Husaynis, and opposition members of the AHC. Plascov said that the Palestinian Congresses were conducted in accordance with prevailing Arab custom. He also said that contrary to the widely held belief outside Jordan the representatives did reflect the feelings of a large segment of the population.[60]

The Transjordanian Government agreed to the unification on 7 December 1948, and on 13 December the Transjordanian parliament approved the creation of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The change of status was reflected by the adoption of this new official name on 21 January 1949.[61] Unification was ratified by a joint Jordanian National Assembly on 24 April 1950 which comprised twenty representatives each from the East and West Bank. The Act of Union contained a protective clause which preserved Arab rights in Palestine "without prejudice to any final settlement".[55][56]

Many legal scholars say the declaration of the Arab League and the Act of Union implied that Jordan's claim of sovereignty was provisional, because it had always been subject to the emergence of the Palestinian state.[62][63] A political union was legally established by the series of proclamations, decrees, and parliamentary acts in December 1948. Abdullah thereupon took the title King of Jordan, and he officially changed the country's name to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in April 1949. The 1950 Act of Union confirmed and ratified King Abdullah's actions. Following the annexation of the West Bank, only two countries formally recognized the union: Britain and Pakistan.[64] Thomas Kuttner notes that de facto recognition was granted to the regime, most clearly evidenced by the maintaining of consulates in East Jerusalem by several countries, including the United States.[65] Joseph Weiler agreed, and said that other states had engaged in activities, statements, and resolutions that would be inconsistent with non-recognition.[66] Joseph Massad said that the members of the Arab League granted de facto recognition and that the United States had formally recognized the annexation, except for Jerusalem.[67] The policy of the U.S. Department, was stated in a paper on the subject prepared for the Foreign Ministers meetings in London in May was in favor of the incorporation of Central Palestine into Jordan, but desired that it be done gradually and not by sudden proclamation. Once the annexation took place, the Department approved of the action "in the sense that it represents a logical development of the situation which took place as a result of a free expression of the will of the people.... The United States continued to wish to avoid a public expression of approval of the union."[68]

The United States government extended de jure recognition to the Government of Transjordan and the Government of Israel on the same day, 31 January 1949.[69] U.S. President Truman told King Abdullah that the policy of the U.S. as regards a final territorial settlement in Palestine had been stated in the General Assembly on 30 November 1948 by the American representative. The U.S. supported Israeli claims to the boundaries set forth in the UN General Assembly resolution of 29 November 1947, but believed that if Israel sought to retain additional territory in Palestine allotted to the Arabs, it should give the Arabs territorial compensation.[70] Clea Bunch said that "President Truman crafted a balanced policy between Israel and its moderate Hashemite neighbours when he simultaneously extended formal recognition to the newly created state of Israel and the Kingdom of Transjordan. These two nations were inevitably linked in the President's mind as twin emergent states: one serving the needs of the refugee Jew, the other absorbing recently displaced Palestinian Arabs. Truman was aware of the private agreements that existed between Jewish Agency leaders and King Abdullah I of Jordan. Thus, it made perfect sense to Truman to favour both states with de jure recognition."[71]

Sandra Berliant Kadosh analyzed U.S. policy toward the West Bank in 1948, based largely on the Foreign Relations Documents of the United States. She noted that the U.S. government believed that the most satisfactory solution regarding the disposition of the greater part of Arab Palestine would be incorporation in Transjordan and that the State Department approved the Principle underlying the Jericho resolutions.[72] Kadosh said that the delegates claimed to represent 90 percent of the population, and that they ridiculed the Gaza government. They asserted that it represented only its eighty-odd members.[73]

Egypt supervised an independent government of Palestine in Gaza as a trustee on behalf of the Arab League.[74] An Egyptian Ministerial order dated 1 June 1948 declared that all laws in force during the Mandate would continue to be in force in the Gaza Strip. Another order issued on 8 August 1948 vested an Egyptian Administrator-General with the powers of the High Commissioner. The All-Palestine Government issued a Declaration of the Independent State of Palestine on 1 October 1948.[75]:294 In 1957, the Basic Law of Gaza established a Legislative Council that could pass laws which were given to the High Administrator-General for approval. In March 1962, a Constitution for the Gaza Strip was issued confirming the role of the Legislative Council.[55]

After the war

All-Palestine government

The All-Palestine Government (Arabic: حكومة عموم فلسطين Hukumat 'umum Filastin) was established by the Arab League on 22 September 1948, during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. It was soon recognized by all Arab League members, except Jordan. Though jurisdiction of the Government was declared to cover the whole of the former Mandatory Palestine, its effective jurisdiction was limited to the Gaza Strip.[76] The Prime Minister of the Gaza-seated administration was named Ahmed Hilmi Pasha, and the President was named Haj Amin al-Husseini,[77] former chairman of the Arab Higher Committee.

Shortly thereafter, the Jericho Conference named King Abdullah I of Transjordan, "King of Arab Palestine".[78] The Congress called for the union of Arab Palestine and Transjordan and Abdullah announced his intention to annex the West Bank. The other Arab League member states opposed Abdullah's plan.

The U.S. advised the Arab states that the U.S. attitude regarding Israel had been clearly stated in the UN by Dr. Jessup on 20 November 1949. He said that the U.S. supported Israeli claims to the boundaries set forth in the UN General Assembly resolution. However, the U.S. believed that if Israel sought to retain additional territory in Palestine it should give the Arabs other territory as compensation.[79] The Israelis agreed that the boundaries were negotiable, but did not agree to the principle of compensation as a precondition. Israel's Foreign Minister Eban stressed that it was undesirable to undermine what had already been accomplished by the armistice agreements, and maintained that Israel held no territory wrongfully, since her occupation of the areas had been sanctioned by the armistice agreements, as had the occupation of the territory in Palestine held by the Arab states.[80]

In late 1949, under the auspices of the UNCCP, their subsidiary Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East, headed by Gordon R. Clapp, recommended four development projects, involving the Wadi Zerqa basin in Jordan, the Wadi Qelt watershed and stream bed in Arab Palestine, the Litani River in Lebanon, and the Ghab valley in Syria.[81][82][83] The World Bank considered the mission's plans positive,[84] and U.S. President Harry Truman subsequently announced that the Foreign Economic Assistance Act of 1950 contained an appropriation of US$27 million for the development projects recommended by the Clapp Mission and to assist Palestinian refugees.[85]

In a diplomatic conversation held on 5 June 1950 between Stuart W. Rockwell of the State Department's Office of African and Near Eastern Affairs and Abdel Monem Rifai, a Counselor of the Jordan Legation. Rifai asked when the U.S. was going to recognize the union of Arab Palestine and Jordan. Rockwell explained the Department's position, stating that it was not the custom of the U.S. to issue formal statements of recognition every time a foreign country changed its territorial area. The union of Arab Palestine and Jordan had been brought about as a result of the will of the people and the U.S. accepted the fact that Jordanian sovereignty had been extended to the new area. Rifai said he had not realized this and that he was very pleased to learn that the U.S. did in fact recognize the union. The U.S. State Department published this memorandum of conversation in 1978.[85]

The All-Palestine Government was under official Egyptian protection,[76] but on the other hand it had no executive role, but rather mostly political and symbolic.[76] Its importance gradually declined, especially with the government seat relocation from Gaza to Cairo, following the Suez Crisis. In 1959, the All-Palestine entity was officially merged into the United Arab Republic, becoming de facto under Egyptian military occupation. The All-Palestine Government is regarded by some as the first attempt to establish an independent Palestinian state, whilst most just saw it as an Egyptian puppet, only to be annulled a few years after its creation by no less than President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt.

Six-Day War (1967)

Between 5 and 10 June 1967, a war – known as the Six-Day War – was fought, in which Israel, defending itself against attacks from many surrounding countries, effectively seized control of the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, the West Bank, including East Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria.

On 9 June 1967, Israeli Foreign Minister Eban assured the U.S. that it was not seeking territorial aggrandizement and had no "colonial" aspirations.[86] U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk stressed to Israel that no settlement with Jordan would be accepted by the global community unless it gave Jordan some special position in the Old City of Jerusalem. The U.S. also assumed Jordan would receive the bulk of the West Bank as that was regarded as Jordanian territory.[87]

On 3 November 1967, U.S. Ambassador Goldberg called on King Hussein of Jordan, saying that the U.S. was committed to the principle of political independence and territorial integrity and was ready to reaffirm it bilaterally and publicly in the Security Council resolution. According to Goldberg, the U.S. believed in territorial integrity, withdrawal, and recognition of secure boundaries. Goldberg said the principle of territorial integrity has two important sub-principles, there must be a withdrawal to recognized and secure frontiers for all countries, not necessarily the old armistice lines, and there must be mutuality in adjustments.[88]

The U.S. President's Special Assistant, Walt Rostow, told Israeli ambassador Harmon that he had already stressed to Foreign Minister Eban that the U.S. expected the thrust of the settlement would be toward security and demilitarisation arrangements rather than toward major changes in the armistice lines. Harmon said the Israeli position was that Jerusalem should be an open city under unified administration, but that the Jordanian interest in Jerusalem could be met through arrangements including "sovereignty". Rostow said the U.S. government assumed (and Harman confirmed) that despite public statements to the contrary, the Government of Israel position on Jerusalem was that which Eban, Harman, and Evron had given several times, that Jerusalem was negotiable.[89]

Rift between Jordan and Palestinian leadership (1970)

After the events of Black September in Jordan, the rift between the Palestinian leadership and the Kingdom of Jordan continued to widen. The Arab League affirmed the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination and called on all the Arab states, including Jordan, to undertake to defend Palestinian national unity and not to interfere in internal Palestinian affairs. The Arab League also 'affirmed the right of the Palestinian people to establish an independent national authority under the command of the Palestine Liberation Organization, the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people in any Palestinian territory that is liberated.' King Ḥussein dissolved the Jordanian parliament. Half of its members had been West Bank representatives. He renounced Jordanian claims to the West Bank, and allowed the PLO to assume responsibility as the Provisional Government of Palestine. The Kingdom of Jordan, Egypt, and Syria no longer act as the legitimate representatives of the Palestinian people, or their territory.[90][91]

Development of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (1974)

At the Rabat summit conference in 1974, Jordan and the other members of the Arab League declared that the Palestinian Liberation Organization was the "sole legitimate representative of the [Arab] Palestinian people", thereby relinquishing to that organization its role as representative of the West Bank.

In a speech delivered on 1 September 1982, U.S. President Ronald Reagan called for a settlement freeze and continued to support full Palestinian autonomy in political union with Jordan. He also said that "It is the United States' position that – in return for peace – the withdrawal provision of Resolution 242 applies to all fronts, including the West Bank and Gaza."[92]

The Amman Agreement of 11 February 1985, declared that the PLO and Jordan would pursue a proposed confederation between the state of Jordan and a Palestinian state.[93] In 1988, King Hussein dissolved the Jordanian parliament and renounced Jordanian claims to the West Bank. The PLO assumed responsibility as the Provisional Government of Palestine and an independent state was declared.[94]

History

Declaration of Independence (1988)

Declassified diplomatic documents reveal that in 1974, on the eve of the UN debate that granted the PLO an observer status, some parts of the PLO leadership were considering to proclaim the formation of a Palestinian government in exile at some point.[95] This plan, however, was not carried out.

The Palestinian Declaration of Independence was approved by the Palestinian National Council (PNC) in Algiers on 15 November 1988, by a vote of 253 in favour, 46 against and 10 abstentions. It was read by Yasser Arafat at the closing session of the 19th PNC to a standing ovation.[36] Upon completing the reading of the declaration, Arafat, as Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization assumed the title of "President of Palestine".[96]

Referring to "the historical injustice inflicted on the Palestinian Arab people resulting in their dispersion and depriving them of their right to self-determination," the declaration recalled the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) and UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (1947 Partition Plan) as supporting the rights of Palestinians and Palestine. The declaration then proclaims a "State of Palestine on our Palestinian territory with its capital Jerusalem".[97][98] The borders of the declared State of Palestine were not specified. The population of the state was referred to by the statement: "The State of Palestine is the state of Palestinians wherever they may be". The state was defined as an Arab country by the statement: "The State of Palestine is an Arab state, an integral and indivisible part of the Arab nation". The declaration was accompanied by a PNC call for multilateral negotiations on the basis of UN Security Council Resolution 242. This call was later termed "the Historic Compromise",[99] as it implied acceptance of the "two-state solution", namely that it no longer questioned the legitimacy of the State of Israel.[98] The PNC's political communiqué accompanying the declaration called only for withdrawal from "Arab Jerusalem" and the other "Arab territories occupied."[100] Arafat's statements in Geneva a month later[101][102] were accepted by the United States as sufficient to remove the ambiguities it saw in the declaration and to fulfill the longheld conditions for open dialogue with the United States.[103][104]

As a result of the declaration, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) convened, inviting Arafat, Chairman of the PLO to give an address. An UNGA resolution was adopted "acknowledging the proclamation of the State of Palestine by the Palestine National Council on 15 November 1988," and it was further decided that "the designation 'Palestine' should be used in place of the designation 'Palestine Liberation Organization' in the United Nations system," and it delegate was assigned a seated in the UN General Assembly immediately after non-member states, and before all other observers.[24][105] One hundred and four states voted for this resolution, forty-four abstained, and two – the United States and Israel – voted against.[55][106] By mid-December, seventy-five states had recognized Palestine, rising to eighty-nine states by February 1989.[75]:49

By the 1988 declaration, the PNC empowered its central council to form a government-in-exile when appropriate, and called upon its executive committee to perform the duties of the government-in-exile until its establishment.[36]

Palestinian Authority (1994)

Under the terms of the Oslo Accords signed between Israel and the PLO, the latter assumed control over the Jericho area of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip on 17 May 1994. On 28 September 1995, following the signing of the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Israeli military forces withdrew from the West Bank towns of Nablus, Ramallah, Jericho, Jenin, Tulkarem, Qalqilya and Bethlehem. In December 1995, the PLO also assumed responsibility for civil administration in 17 areas in Hebron.[107] While the PLO assumed these responsibilities as a result of Oslo, a new temporary interim administrative body was set up as a result of the Accords to carry out these functions on the ground: the Palestinian National Authority (PNA).

An analysis outlining the relationship between the PLO, the PNA (or PA), Palestine and Israel in light of the interim arrangements set out in the Oslo Accords begins by stating that, "Palestine may best be described as a transitional association between the PA and the PLO." It goes on to explain that this transitional association accords the PA responsibility for local government and the PLO responsibility for representation of the Palestinian people in the international arena, while prohibiting it from concluding international agreements that affect the status of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. This situation is said to be accepted by the Palestinian population insofar as it is viewed as a temporary arrangement.[108]

In 2005, following the implementation of Israel's unilateral disengagement plan, PNA gained full control of the Gaza Strip with the exception of its borders, airspace, and territorial waters.[iii] This increased the percentage of land in the Gaza strip nominally governed by the PA from 60 percent to 100 percent.

The West Bank and Gaza Strip continued to be considered by the international community to be Occupied Palestinian Territory, notwithstanding the 1988 declaration of Palestinian independence, the limited self-government accorded to the Palestinian Authority as a result of the 1993 Oslo Accords, and Israel's withdrawal from Gaza as part of the Israel's unilateral disengagement plan of 2005, which saw the dismantlement of four Israeli settlements in the West Bank and all settlements in the Gaza Strip.[109]

In March 2008, it was reported that the PA was working to increase the number of countries that recognize Palestine and that a PA representative had signed a bilateral agreement between the State of Palestine and Costa Rica.[110] A recent Al-Haq position paper said the reality is that the PA has entered into various agreements with international organizations and states. These instances of foreign relations undertaken by the PA signify that the Interim Agreement is part of a larger on-going peace process, and that the restrictions on the foreign policy operations of the PA conflict with the inalienable right of the Palestinian people to self-determination, now a norm with a nature of jus cogens, which includes a right to engage in international relations with other peoples.[111]

When the PA is exercising the power that is granted to them by the Oslo Accords, they’re acting in the capacity of an agency whose authority is based on an agreement between Israel and the PLO and not as a state.[112]

Split of the Fatah and Hamas

In 2007, after Hamas's legislative victories, the Fatah and Hamas engaged into a violent conflict, taking place mainly in the Gaza Strip, leading to effective collapse of the Palestinian national unity government. After the takeover in Gaza by Hamas on 14 June 2007, Palestinian Authority Chairman Abbas dismissed the Hamas-led government and appointed Salam Fayyad as Prime Minister. Though the new government's authority is claimed to extend to all Palestinian territories, in effect it became limited to the West Bank, as Hamas hasn't recognized the move and continued to rule the Gaza Strip. While PNA budget comes mainly from various aid programs and support of the Arab League, the Hamas Government in Gaza became dependent mainly on Iran until the eruption of the Arab Spring.

2013 change of name

Following the successful passage of the 2012 United Nations status resolution which changed Palestine's status at the UN to that of observer state, on 3 January 2013, Abbas signed a presidential decree 1/2013[113] officially changing the name of the 'Palestinian Authority' to the 'State of Palestine' The decree stated that "Official documents, seals, signs and letterheads of the Palestinian National Authority official and national institutions shall be amended by replacing the name ‘Palestinian National Authority’ whenever it appears by the name ‘State of Palestine’ and by adopting the emblem of the State of Palestine."[114] According to international lawyer John V. Whitbeck the decree results in absorbing of the Palestinian Authority into the State of Palestine.[113] On 8 January 2013 the Minister of Communication Safa Nassereddin, said that because issuing new stamps requires Israeli approval to print them and bring them into the country, it was decided that the new stamps will be printed in Bahrain and the first of these stamps will be used by Palestinian embassies and other diplomatic missions abroad.[115]

On 5 January 2013 Abbas ordered all Palestinian embassies to change any official reference to the Palestinian Authority into State of Palestine.[116][117] Missions in countries that voted "against" UNGA resolution 67/19 of 2012 are ordered to consult the foreign ministry.[118] Three days later, Omar Awadallah, a foreign ministry official, said that those missions should also use the new name.[7] Some of the countries themselves, such as Norway, Sweden and Spain, stick to the Palestinian Authority term even though they voted "in favor" of the UNGA resolution.[119]

On 6 January 2013, Abbas ordered his cabinet of ministers to prepare regulations to issue new Palestinian passports, official signs and postage stamps in the name of the 'State of Palestine'.[120][121] Two days later, following a negative reaction by Israel,[122] it was announced that the change will not apply to documents used at Israel checkpoints in the West Bank[119] and Israeli crossings,[7] unless there is a further decision by Abbas.[122] Saeb Erekat then said the new emblem will be used in correspondence with countries that have recognized a state of Palestine.[122]

For the time being the governments of the renamed Authority established in 1994 and of the State established in 1988 remain distinct.[123] On 5 January 2013 it was announced that it is expected the PLO Central Council would take over the functions of the Palestinian Authority’s government and parliament.[124] On the following day, Saeb Erekat, head of the PLO negotiations department, said that the authority should draft a new constitution.[118]

Following the change in name, Turkey became the first state to recognize this change, and on 15 April 2013, the Turkish Consul-General in East Jerusalem Şakir Torunlar presented his credentials as first Turkish Ambassador to the State of Palestine to Palestinian President in Ramallah.[125]

Palestine in the United Nations

2011 United Nations membership application

After a two-year impasse in negotiations with Israel, the Palestinian Authority sought to gain recognition as a state according to its 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital from the UN General Assembly in September 2011.[126] A successful application for membership in the UN would require approval from the UN Security Council and a two-thirds majority in the UN General Assembly.

On the prospect of this being successful, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice alluded to a potential U.S. government withdrawal of UN funding: "This would be exceedingly politically damaging in our domestic context, as you can well imagine. And I cannot frankly think of a greater threat to our ability to maintain financial and political support for the United Nations in Congress than such an outcome."[127] On 28 June, the U.S. Senate passed S.Res. 185 calling on U.S. President Barack Obama to veto the motion and threatening a withdrawal of aid to the West Bank if the Palestinians followed through on their plans.[128] At the likely prospect of a veto, Palestinian leaders signalled they might opt instead for a more limited upgrade to "non-member state" status, which requires only the approval of the UN General Assembly.[129]

Mahmoud Abbas stated he would accept a return to negotiations and abandon the decision if the Israelis agree to the 1967 borders and the right of return for Palestinian refugees. Israel labelled the plan as a unilateral step,[130] to which Foreign Minister Erekat replied,

"We are not going [to the UN] for a unilateral declaration of the Palestinian state. We declared our state in 1988 and we have embassies in more than 130 countries and more countries are recognising our state on the 1967 borders. The recognition of the Palestinian state is a sovereignty decision by the countries and it doesn't need to happen through the UN."[130]

The Arab League formally backed the plan in May,[129] and was officially confirmed by the PLO on 26 June.[131]

On 11 July, the Quartet on the Middle East met to discuss a return to negotiations, but the meeting produced no result. On 13 July, in an interview with Haaretz, Palestinian Ambassador to the United Nations Riyad Mansour claimed that 122 states had so far extended formal recognition to the Palestinian state.[132] On the following day, the Arab League released a draft statement which declared a consensus to "go to the United Nations to request the recognition of the State of Palestine with Al Quds as its capital and to move ahead and request a full membership."[129] The league's secretary-general, Nabil al-Arabi, confirmed the statement and said that the application for membership will be submitted by the Arab League.[133] On 18 July, Syria announced that it had formally recognised the State of Palestine, the last Arab state to do so.[134] The decision was welcomed by the league,[134] but met with criticism from some, including former Lebanese prime minister Selim al-Hoss: "Syria has always been calling for the liberation of Palestine from Israeli occupation and ambitions. The latest stance, however, shows that [Syria] has given up on a national policy that has spanned several decades. ... Why this abandonment of a national principle, and what is the motive behind it? There is no motive except to satisfy international powers that seek to appease Israel".[135]

On 23 September, Abbas delivered to the UN Secretary-General the official application for recognition of a Palestinian state by the UN and a membership in the same organization.[136][137] On 11 November a report was approved by the Security Council which concluded that the Council had been unable "to make a unanimous recommendation" on membership for Palestine.[138]

2011 UNESCO membership

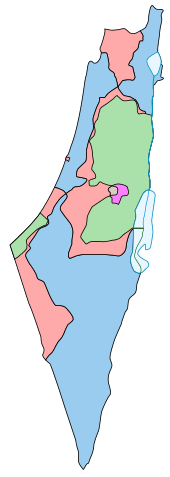

In favour Against Abstentions Absent

non-members / ineligible to vote

In favour Against Abstentions Absent Non-members

The PLO was accorded observer status at UNESCO in 1974. In 1989, an application for the admission of Palestine as a member state was submitted by a group of seven states during the 131st session of UNESCO's Executive Board.[139] The board postponed a decision until the next session, and the item was included on each session's agenda thereafter, being repeatedly deferred.[140] During the board's 187th session in September 2011, a draft resolution was presented by 24 states requesting that the application be considered and Palestine be granted membership in the organisation. Following consultations between the representatives of the 58-member board, the draft resolution was put for voting on 5 October. The board voted in favour of recommending the application, winning the approval of 40 states.[141][142] The resolution to admit Palestine as the agency's 195th member state was adopted at the 36th General Conference on 31 October.[144] Of the 185 dues-paying members eligible for voting, 107 were in favour, 14 were against, 52 abstained and 12 were absent.[145][146] The resolution was submitted by a total of 43 states.[147] Its membership was ratified on 23 November.[148]

2012 United Nations observer state status

By September 2012, with their application for full membership stalled, Palestine had decided to pursue an upgrade in status from "observer entity" to "non-member observer state". On 27 November it was announced that the appeal had been officially made, and would be put to a vote in the General Assembly on 29 November, where their status upgrade was expected to be supported by a majority of states. In addition to granting Palestine "non-member observer state status", the draft resolution "expresses the hope that the Security Council will consider favorably the application submitted on 23 September 2011 by the State of Palestine for admission to full membership in the United Nations, endorses the two state solution based on the pre-1967 borders, and stresses the need for an immediate resumption of negotiations between the two parties."

On 29 November 2012, in a 138–9 vote (with 41 abstentions and 5 absences),[28] General Assembly resolution 67/19 passed, upgrading Palestine to "non-member observer state" status in the United Nations.[30][31] The new status equates Palestine's with that of the Holy See. Switzerland was also a non-member observer state until 2002. The change in status was described by The Independent as "de facto recognition of the sovereign state of Palestine".[149]

The vote was a historic benchmark for the recognition of the State of Palestine and its people, while a diplomatic setback for Israel and the United States. Status as an observer state in the UN will allow the State of Palestine to participate in general debate at the General Assembly, to co-sponsor resolutions, to join treaties and specialized UN agencies.[32] Even as a non-member state, the Palestinians could join influential international bodies such as the World Trade Organization, the World Health Organization, the World Intellectual Property Organization, the World Bank and the International Criminal Court,[150] where the Palestinian Authority tried to have alleged Israeli war crimes in Gaza (2008-2009) investigated. Earlier, in April 2012, prosecutors had refused to open the investigation, saying it was not clear if the Palestinians were qualified as a state - as only states can recognize the court's jurisdiction.[150] But the prosecutor, ms. Fatou Bensouda, confirmed explicitly in 2014 that the upgrade of November 2012 qualified the state of Palestine to join the Rome statute.[151] On 31 December 2014 Palestinian President Abbas signed a declaration in which Palestine recognized the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court for any crimes committed in the Palestinian territory since 13 June 2014.[152]

The UN nod can also help to affirm the borders of the Palestinian territories that Israel occupied in 1967.[153] Theoretically Palestine could even claim legal rights over its territorial waters and air space as a sovereign state recognised by the UN.

The UN has, after the resolution was passed, permitted Palestine to title its representative office to the UN as "The Permanent Observer Mission of the State of Palestine to the United Nations",[33] seen by many as a reflexion of the UN's de facto recognition of the State of Palestine's sovereignty,[30] and Palestine has started to re-title its name accordingly on postal stamps, official documents and passports.[31][154] The Palestinian authorities have also instructed its diplomats to officially represent "The State of Palestine", as opposed to the "Palestinian National Authority".[31] On 17 December 2012, UN Chief of Protocol Yeocheol Yoon decided that "the designation of 'State of Palestine' shall be used by the Secretariat in all official United Nations documents".[34]

Government

The State of Palestine consists of the following institutions that are associated with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO):

- President of the State of Palestine[155][iv] – appointed by the Palestinian Central Council[156]

- Palestinian National Council – the legislature that established the State of Palestine[5]

- Executive Committee of the Palestine Liberation Organization – performs the functions of a government in exile,[30][36][157][158] maintaining an extensive foreign-relations network

These should be distinguished from the President of the Palestinian National Authority, Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) and PNA Cabinet, all of which are instead associated with the Palestinian National Authority.

The State of Palestine's founding document is the Palestinian Declaration of Independence,[5] and it should be distinguished from the unrelated PLO Palestinian National Covenant and PNA Palestine Basic Law.

Palestine is divided into sixteen administrative divisions. Five of these divisions, the governorates of Deir al-Balah, Gaza, North Gaza, Khan Yunis and Rafah, are in the Gaza Strip. The combined area of these governorates is 360 square kilometres (360,000 dunams), and their total population in 2007 was 1,416,539. The remaining eleven governorates are in the West Bank, with a population of 2,345,107 in 2007, living in an area of 5,671 square kilometres (5,671,000 dunams).[159]

The governorates in the West Bank are grouped into three areas per the Oslo II Accord. Area A forms 18% of the West Bank by area, and is administered by the Palestinian government.[160][161] Area B forms 22% of the West Bank, and is under Palestinian civil control, and joint Israeli-Palestinian security control.[160][161] Area C, except East Jerusalem, forms 60% of the West Bank, and is administered by the Israeli Civil Administration, except that the Palestinian government provides the education and medical services to the 150,000 Palestinians in the area.[160] More than 99% of Area C is off limits to Palestinians.[162] There are about 330,000 Israelis living in settlements in Area C,[163] in the Judea and Samaria Area. Although Area C is under martial law, Israelis living there are judged in Israeli civil courts.[164]

East Jerusalem, the proclaimed capital of Palestine, is administered as part of the Jerusalem District of Israel, but is claimed by Palestine as part of the Jerusalem Governorate. It was annexed by Israel in 1980,[160] but this annexation is not recognised by any other country.[165] Of the 456,000 people in East Jerusalem, rough 60% are Palestinian and 40% are Israeli.[160][166]

International recognition and foreign relations

Representation of the State of Palestine is performed by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In states that recognise the State of Palestine it maintains embassies. The Palestine Liberation Organization is represented in various international organizations as member, associate or observer. Because of inconclusiveness in sources[167] in some cases it is impossible to distinguish whether the participation is executed by the PLO as representative of the State of Palestine, by the PLO as a non-state entity or by the PNA.

On 15 December 1988, the State of Palestine's declaration of independence of November 1988 was acknowledged in the General Assembly with Resolution 43/177.[168]

As of 30 October 2014, 135 (69.9%) of the 193 member states of the United Nations have recognised the State of Palestine. Many of the countries that do not recognise the State of Palestine nevertheless recognise the PLO as the "representative of the Palestinian people". The PLO's executive committee is empowered by the PNC to perform the functions of government of the State of Palestine.[36]

On 29 November 2012,[28] UN General Assembly resolution 67/19 passed, upgrading Palestine to "non-member observer state" status in the United Nations.[30][31] The change in status was described as "de facto recognition of the sovereign state of Palestine".[149]

On 3 October 2014, new Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven used his inaugural address in parliament to announce that Sweden would recognise the state of Palestine. The official decision to do so was made on 30 October, making Sweden the first long-term member country of the EU to recognise the state of Palestine. Most of the EU's 28 member states have refrained from recognising Palestinian statehood and those that do - such as Hungary, Poland and Slovakia - did so before joining the bloc.[169][170][171]

On 13 October 2014, the UK House of Commons voted by 274 to 12 in favour of recognising Palestine as a state.[172] The House of Commons backed the move "as a contribution to securing a negotiated two-state solution" - although less than half of MPs took part in the vote. However, the UK government is not bound to do anything as a result of the vote: its current policy is that it "reserves the right to recognise a Palestinian state bilaterally at the moment of our choosing and when it can best help bring about peace".[173]

On 2 December 2014, the French parliament voted by 331 to 151 in favour of urge their government to recognise Palestine as a sate. The text, proposed by the ruling Socialists and backed by left-wing parties and some conservatives, asked the government to "use the recognition of a Palestinian state with the aim of resolving the conflict definitively".[174]

On 31 December 2014, the United Nations voted down a resolution demanding the end of Israeli occupation and statehood by 2017. Eight members voted for the Resolution (Russia, China, France, Argentina, Chad, Chile, Jordan, Luxembourg), however following strenuous US and Israeli efforts to defeat the resolution,[175] it did not get the minimum of nine votes needed to pass the resolution. Australia and the United States voted against the resolution, with five other nations abstaining.[176][177][178]

On 10 January 2015, the first Palestinian embassy in a western European country is open in Stockholm, Sweden.[179]

Multilateral treaties

The State of Palestine is a party to several multilateral treaties, registered with five depositaries: the United Kingdom, UNESCO, United Nations, the Netherlands and Switzerland. The ratification of the UNESCO conventions took place in 2011/2012 and followed Palestine becoming a member of UNESCO, while the ratification of the other conventions were performed in 2014 while negotiations with Israel were in an impasse.

| Depositary Country/organization | Depositary organ | Number of treaties | Examples | Date of first ratification/accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands | Ministry of Foreign Affairs | 1[180] | Convention respecting the laws and customs of war on land | 2 April 2014 |

| Russia | 1[181] | Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons | 10 February 2015 | |

| Switzerland | Federal Council | 7[182][183] | Geneva Conventions and Protocols | 2 April 2014 |

| UNESCO | Director-General | 8[184] | Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage | 8 December 2011 |

| United Nations | Secretary-General | 30[185] | Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations Statute of the International Criminal Court | 9 April 2014 |

| United Kingdom | Foreign and Commonwealth Office | 2[186][187] | UNESCO Constitution Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons | 23 November 2011 |

In an objection of 16 May 2014, Israel informed the Secretary General of the United Nations that it did not consider that "Palestine" (parenthesis added by Israel) met the definition of statehood and that it's ratification had was "without effect upon Israel's treaty relations under the Convention".[188] The United States and Canada lodged similar objections.[189][190]

European Union position

In March 1999, the European Union confirmed in the Berlin Declaration the Palestinian right to self-determination, including the right to a viable and peaceful sovereign Palestinian State. This right was declared "not subject to any veto".[191]

The EU supports a Palestinian state within the pre-1967 borders, with only minor modifications mutually agreed.[192] Further, the EU advocates Jerusalem as the future capital of both Israel and Palestine.[193]

Legal status

There are a wide variety of views regarding the status of the State of Palestine, both among the states of the international community and among legal scholars. The existence of a state of Palestine, although controversial, is a reality in the opinions of the states that have established bilateral diplomatic relations.[194][195][196][197]

Statehood for the purposes of the UN Charter

Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) had been recognized as "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people," competent on all matters concerning the question of Palestine by the UN General Assembly in addition to the right of the Palestinian people in Palestine to national independence and sovereignty, and was granted observer status at the UN General Assembly as a "non-state entity", from 1974.[18] In mid-November 2011, the PLO submitted an official application to become a full member of the UN.[136] A successful application would require approval from the UN Security Council and a two-thirds majority in the UN General Assembly. However, the Security Council's membership committee deadlocked on the issue and had been "unable to make a unanimous recommendation to the Security Council".[198] The report was the result of seven weeks of meetings, detailing myriad disagreements between the council members on whether Palestine fulfills the requirements set forth in the U.N. charter for members countries.[138] With their application for full membership stalled, the PLO sought an upgrade in status, from "observer entity" to "non-member observer state". In November 2012, UN General Assembly accepted the resolution upgrading Palestine to "non-member observer state" within the United Nations system, reasserting PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people.[149]

The UN Charter protects the territorial integrity or political independence of any state from the threat or use of force. Philip Jessup served as a representative of the United States to the United Nations and as a Judge on the International Court of Justice. During the Security Council hearings regarding Israel's application for membership in the UN, he said:

"[W]e already have, among the members of the United Nations, some political entities which do not possess full sovereign power to form their own international policy, which traditionally has been considered characteristic of a State. We know however, that neither at San Francisco nor subsequently has the United Nations considered that complete freedom to frame and manage one's own foreign policy was an essential requisite of United Nations membership.... ...The reason for which I mention the qualification of this aspect of the traditional definition of a State is to underline the point that the term "State", as used and applied in Article 4 of the Charter of the United Nations, may not be wholly identical with the term "State" as it is used and defined in classic textbooks on international law."[199]

In 2009, Riyad al-Maliki, the Palestinian Foreign Minister of the Palestinian National Authority, provided proof that Palestine had been extended legal recognition as a state by 67 other countries, and had bilateral agreements with states in Latin America, Asia, Africa and Europe.[200]

Declaration and Act of State Doctrine

Many states have recognized the State of Palestine since 1988. Under the principles of customary international law, when a government is recognized by another government, recognition is retroactive in effect, and validates all the actions and conduct of the government so recognized from the commencement of its existence.[201]

Stephen Talmon notes that many countries have a formal policy of recognizing states, not their governments. In practice, they usually make no formal declarations regarding recognition. He cites several examples including a memorandum on US recognition policy and practice, dated 25 September 1981, which said that recognition would be implied by the US government's dealings with the new government.[202] Many countries have expressed their intention to enter into relations with the State of Palestine. The US formally recognized the West Bank and Gaza Strip as "one area for political, economic, legal and other purposes" in 1997 at the request of the Palestinian Authority. At that time, it asked the public to take notice of that fact through announcements it placed in the Federal Register, the official journal of the US government.[203] The USAID West Bank/Gaza,[204] has been tasked with "state-building" projects in the areas of democracy, governance, resources, and infrastructure. Part of the USAID mission is to "provide flexible and discrete support for implementation of the Quartet Road Map",[205] an internationally backed plan which calls for the progressive development of a viable Palestinian State in the West Bank and Gaza. The European Union (EU) has announced similar external relations programs with the Palestinian Authority.[206]

The view of the European states, which did not extend full recognition was expressed by French President François Mitterrand who stated: "Many European countries are not ready to recognize a Palestine state. Others think that between recognition and non-recognition there are significant degrees; I am among these."[106] But, after the PLO recognized the state of Israel, Mitterrand welcomed the PLO leader, Yasser Arafat, in Paris, in May 1989.[207]

Consequences of the occupation

After 1967, a number of legal arguments were advanced which dismissed the right of Palestinians to self-determination and statehood. They generally proposed that Palestine was a land void of a legitimate sovereign and supported Israeli claims to the remaining territory of the Palestine Mandate.[208][209] Historian and journalist, Gershom Gorenberg, says that outside of the pro-settlement community in Israel, these positions are considered quirky. He says that, while the Israeli government has used them for PR purposes abroad, it takes entirely different positions when arguing real legal cases before the Israeli Supreme Court. In 2005 Israel decided to dismantle all Israeli settlements in the Gaza Strip and four in the northern West Bank. Gorenberg notes, the government's decision was challenged in the Supreme Court by settlers, and the government won the case by noting the settlements were in territory whose legal status was that of 'belligerent territory'. The government argued that the settlers should have known the settlements were only temporary.[210]

Most UN member states questioned the claim that Israel held better title to the land than the inhabitants, and stressed that statehood was an inalienable right of the Palestinian people.[211] Legal experts, like David John Ball, concluded that "the Palestinians, based on the principles of self-determination and the power of the U.N., appear to hold better title to the territory."[212] The International Court of Justice subsequently reaffirmed the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination and the prohibition under customary and conventional international law against acquisition of territory by war.

The Israeli Supreme Court, sitting as the High Court of Justice, cited a case involving the disengagement from Gaza and said that "The Judea and Samaria areas are held by the State of Israel in belligerent occupation. The long arm of the state in the area is the military commander. He is not the sovereign in the territory held in belligerent occupation. His power is granted him by public international law regarding belligerent occupation. The legal meaning of this view is twofold: first, Israeli law does not apply in these areas. They have not been "annexed" to Israel. Second, the legal regime which applies in these areas is determined by public international law regarding belligerent occupation."[213]

The court said that most Israelis in Gaza did not own the land they built on there. "They acquired their rights from the military commander, or from persons acting on his behalf. Neither the military commander nor those acting on his behalf are owners of the property, and they cannot transfer rights better than those they have. To the extent that the Israelis built their homes and assets on land which is not private ('state land'), that land is not owned by the military commander. His authority is defined in regulation 55 of The Hague Regulations. [...] The State of Israel acts [...] as the administrator of the state property and as usufructuary of it."[214]

Decisions of international and national tribunals

The U.S. State Department Digest of International Law says that the terms of the Treaty of Lausanne provided for the application of the principles of state succession to the "A" Mandates. The Treaty of Versailles (1920) provisionally recognized the former Ottoman communities as independent nations. It also required Germany to recognize the disposition of the former Ottoman territories and to recognize the new states laid down within their boundaries. The Treaty of Lausanne required the newly created states that acquired the territory to pay annuities on the Ottoman public debt, and to assume responsibility for the administration of concessions that had been granted by the Ottomans. A dispute regarding the status of the territories was settled by an Arbitrator appointed by the Council of the League of Nations. It was decided that Palestine and Transjordan were newly created states according to the terms of the applicable post-war treaties. In its Judgment No. 5, The Mavrommatis Palestine Concessions, the Permanent Court of International Justice also decided that Palestine was responsible as the successor state for concessions granted by Ottoman authorities. The Courts of Palestine and Great Britain decided that title to the properties shown on the Ottoman Civil list had been ceded to the government of Palestine as an allied successor state.[43]

State succession

A legal analysis by the International Court of Justice noted that the Covenant of the League of Nations had provisionally recognized the communities of Palestine as independent nations. The mandate simply marked a transitory period, with the aim and object of leading the mandated territory to become an independent self-governing State.[215] The Court said that specific guarantees regarding freedom of movement and access to the Holy Sites contained in the Treaty of Berlin (1878) had been preserved under the terms of the Palestine Mandate and a chapter of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine.[216] In a separate opinion, Judge Higgins argued that since United Nations Security Council Resolution 242 in 1967 to resolution 1515 in 2003, the "key underlying requirements" have been that "Israel is entitled to exist, to be recognized, and to security, and that the Palestinian people are entitled to their territory, to exercise self-determination, and to have their own State", with resolution 1515 endorsing the Road map for peace proposed by the Middle East Quartet, as a means to achieve these obligations through negotiation.[217]

Article 62 (LXII) of the Treaty of Berlin, 13 July 1878[218] dealt with religious freedom and civil and political rights in all parts of the Ottoman Empire.[219] The guarantees have frequently been referred to as "religious rights" or "minority rights". However, the guarantees included a prohibition against discrimination in civil and political matters. Difference of religion could not be alleged against any person as a ground for exclusion or incapacity in matters relating to the enjoyment of civil or political rights, admission to public employments, functions, and honors, or the exercise of the various professions and industries, "in any locality whatsoever."

The resolution of the San Remo Conference contained a safeguarding clause for all of those rights. The conference accepted the terms of the Mandate with reference to Palestine, on the understanding that there was inserted in the process-verbal a legal undertaking by the Mandatory Power that it would not involve the surrender of the rights hitherto enjoyed by the non-Jewish communities in Palestine.[220] The draft mandates for Mesopotamia and Palestine, and all of the post-war peace treaties contained clauses for the protection of minorities. The mandates invoked the compulsory jurisdiction of the Permanent Court of International Justice in the event of any disputes.[221]

Article 28 of the Mandate required that those rights be safeguarded in perpetuity, under international guarantee.[215] The General Assembly's Plan for the Future Government of Palestine placed those rights under UN protection as part of a minority protection plan.[222] It required that they be acknowledged in a Declaration, embodied in the fundamental laws of the states, and in their Constitutions. The partition plan also contained provisions that bound the new states to international agreements and conventions to which Palestine had become a party and held them responsible for its financial obligations.[223] The Declarations of the Independent State of Israel and the Independent State of Palestine acknowledged the protected rights and were accepted as being in line with UN resolution 181(II).[224]

Opinions of officials and legal scholars

Jacob Robinson was a legal advisor to the United Nations delegation of the Jewish Agency for Palestine during the special session of the General Assembly in 1947.[225] He advised the Zionist Executive that the provisional states had come into existence as a result of the resolution of 29 November 1947.[75]:279

L.C. Green explained that "recognition of statehood is a matter of discretion, it is open to any existing state to accept as a state any entity it wishes, regardless of the existence of territory or an established government."[226]

Alex Takkenberg writes that while "there is no doubt that the entity 'Palestine' should be considered a state in statu nascendi and although it is increasingly likely that the ongoing peace process will eventually culminate in the establishment of a Palestinian state, it is premature to conclude that statehood, as defined by international law, is at present (spring 1997) firmly established."[227] Referring to the four criteria of statehood, as outlined in the 1933 Montevideo Convention – that is, a permanent population, a defined territory, government and the capacity to enter into relations with other states – Takkenberg states that the entity known as Palestine does not fully satisfy these criteria.[227]