Squatting position

Squatting is a posture where the weight of the body is on the feet (as with standing) but the knees are bent either fully (full or deep squat) or partially (partial, standing, half, semi, parallel or monkey squat). In contrast, sitting, involves taking the weight of the body, at least in part, on the buttocks against the ground or a horizontal object such as a chair seat. Crouching may involve squatting or kneeling. It is possible to squat with one leg and assume another position (such as kneeling) with the other leg.[1] Among Chinese, Southeast Asian, and Eastern European adults, squatting often takes the place of sitting or standing.[2]

Young children

Young children squat instinctively as a continuous movement from standing up whenever they want to lower themselves to ground level. One and two year olds can commonly be seen playing in a stable squatting position, with feet wide apart and bottom not quite touching the floor, although at first they need to hold onto something to stand up again.[3]

Resting position

Full squatting involves resting one's weight on the feet with the buttocks resting on the backs of the calves. It may be used as a posture for resting or working at ground level particularly where the ground is too dirty or wet to sit or kneel.[1]

Most western adults cannot place their heels flat on the ground when squatting because of shortened Achilles tendons largely caused by habitually:[4]

- sitting on chairs or seats

- wearing shoes with heels (especially high heels)

For this reason the squatting position is usually not sustainable for them for more than a few minutes as heels-up squatting is a less stable position than heels-down squatting.[5][6]

Catchers in baseball and wicket-keepers in cricket assume full squatting positions.

Childbirth position

Engelmann's seminal work "Labor among primitive peoples" publicised the childbirth positions amongst primitive cultures to the Western world. They frequently use squatting, standing, kneeling and all fours positions, often in a sequence.[7]

Various people have promoted the adoption of these alternative birthing positions, particularly squatting, for Western countries, such as Grantly Dick-Read, Janet Balaskas, Moysés Paciornik and Hugo Sabatino. The adoption of these alternative positions is also promoted by the natural childbirth movement.

The squatting position gives a greater increase of pressure in the pelvic cavity with minimal muscular effort. The birth canal will open 20 to 30% more in a squat than in any other position. It is recommended for the second stage of childbirth.[8]

As most Western adults find it difficult to squat with heels down, compromises are often made such as putting a support under the elevated heels or another person supporting the squatter.[9]

Sexual position

An uncommon variant of the "cowgirl" sexual position, with the woman on in a squatting position over the man, lying on his back. Sometimes referred to as a frog squat.

Female urination position

When not urinating into a toilet, squatting is the one way for a female to direct the urine stream (although many women find that they can do so standing up). If done this way, the urine will go forward downwards. Some females use one or both hands to focus the direction of the urine stream, which is more easily achieved while in the squatting position.

Acceptability of outdoor urination in a public place other than at a public urinal varies with the situation and with customs. In Western countries, males typically do this standing up, while females squat.

Hovering, often used to avoid sitting on potentially unclean toilet seats, may leave urine behind in the bladder.[10]

Defecation position

The squatting defecation posture involves squatting by standing with knees and hips sharply bent and the buttocks suspended near the ground. Squat toilets are designed to facilitate this posture. This is less common in the Western world.

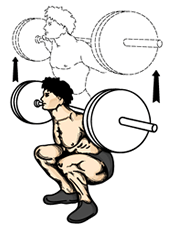

Dynamic exercise

In strength training, the squat is a full body exercise that trains primarily the muscles of the thighs, hips and buttocks, as well as strengthening the bones, ligaments and insertion of the tendons throughout the lower body. Squats are considered a vital exercise for increasing the strength and size of the legs and buttocks.

Yoga

Upavesāsana (literally sitting down pose) also known as the Yoga Squat, is an asana. Its name is often confused with mālāsana, a similar pose practiced with the feet together and the arms bound around the back.

The asana is a squat with heels flat on the floor and hip-width apart (or slightly wider if necessary), toes pointing out on a diagonal. The torso is brought forward between the thighs, elbows are braced against the inside of the knees, and the hands press together in front of the chest in Añjali Mudrā.[11]

Partial squat

A partial squat (also known as standing, half, semi, parallel ) is an intermediate stage between standing and full squatting, that is, standing but with the knees bent. (In contrast, stooping involves bending at the waist rather than just the hips and knees). This may be used in a variety of contexts often as a "ready for action" posture:

- the batsman's posture in cricket when waiting for a delivery.

- waiting to receive a serve in tennis

- used in the Alexander technique, as "the monkey squat" also known as the "position of mechanical advantage"[12]

- to avoid back strain it is important to bend the knees whenever you lift a heavy object.[13]

- plié in ballet is a type of partial squat balanced on the toes only and the legs turned outwards. (The grand plié has the thighs parallel to the ground like a parallel squat or demi-plie where the thighs are at about a 45% angle to the ground).

- the parallel squat, often used in weight training, is just short of a full squat where the thighs are parallel to the ground.

- the most widely used martial arts stance is a shallow standing squat. This position is generally employed as it is a neutral and agile position from which both attacks and defences may be launched. It provides for the delivery of force when attacking and stability when defending.

- ready for action in sumo wrestling.

- Monkey Kung Fu a Chinese martial art which utilizes ape or monkey-like movements as part of its technique.

- a Besti squat is a figure skating move.

- twerking is "to dance to popular music in a sexually provocative manner involving thrusting hip movements and a low squatting stance".[14]

Lunge

A lunge is a variation of the partial squat where a leg is moved forwards with the knee bent but the other remains straight thus moving the upper body forward in line with the bent knee. For example:

- the snooker playing posture

- the fencing lunge

- the lunge as a weight training or strength training exercise.

Walking

Stalking or prowling is essentially walking while in or close to a full squat. This is designed to be a walk that maintains a low profile.

Health effects

There is increased incidence of knee osteoarthritis amongst squatters who squat for hours a day for many years.[15] There is evidence that sustained squatting may cause bilateral peroneal nerve palsy. A common name for this affliction is squatter's palsy although there may be reasons other than squatting for this to occur.[16][17][18]

Tetralogy of Fallot

Older children will often squat during a Tetralogy of Fallot "tet spell". This increases systemic vascular resistance and allows for a temporary reversal of the shunt. It increases pressure on the left side of the heart, decreasing the right to left shunt thus decreasing the amount of deoxygenated blood entering the systemic circulation.[19][20]

Squatting facets

The existence of squatting facets on the distal tibia and talar articular surfaces of skeletons, which result from contact between the two bones during hyperdorsiflexion, have been used as markers to indicate if that person habitually squatted.[21][22]

See also

- Human positions

- Neutral spine

- Squat thrust

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hewes GW: ' World distribution of certain postural habits' American Anthropologist, 57, (1955), 231-44

- ↑ Dobrzynski, Judith H. (2004-10-17). "An Eye on China's Not So Rich and Famous". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ↑ Slentz K, Krogh S Early Childhood Development and Its Variations (2001)

- ↑ John Naish (2013-03-04). "Sitting down can send you to an early grave: Why sofas (and your office chair) should carry a health warning". Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ Mauss, Marcel. Les Techniques du corps 1934. Journal de Psychologie 32 (3-4). Reprinted in Mauss, Sociologie et anthropologie, 1936, Paris: PUF.

- ↑ Bookspan, Jolie. "Save knees when squatting". Healthline.com. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ Engelmann GJ Labor among primitive peoples (1883)

- ↑ Russell JG. Moulding of the pelvic outlet. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 1969;76:817-20.

- ↑ "Balaskas J Using the squatting position during labour and for birth" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ "Preventing kidney infection". nhs.uk. National Health Service. December 11, 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "Garland Pose". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ "The Monkey Squat". easyvigour.net.nz/. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ↑ "Lifting technique". Back.com. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ Twerk, Oxford Dictionaries Online. Retrieved August 28, 2013

- ↑ Liu CM, Xu L Retrospective study of squatting with prevalence of knee osteoarthritis - 2007

- ↑ Macpherson JM, Gordon AJ Squatter's palsy British Medical Journal, 1983

- ↑ Kumaki DJ. The facts of Kathmandu: squatter's palsy. 2 January 1987;257(1):28.

- ↑ "Toğrol E. Bilateral peroneal nerve palsy induced by prolonged squatting. Mil Med. 2000 Mar;165(3):240-2". Findarticles.com. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ Murakami T (2002). "Squatting: the hemodynamic change is induced by enhanced aortic wave reflection". Am. J. Hypertens. 15 (11): 986–8. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(02)03085-6. PMID 12441219.

- ↑ Guntheroth WG, Mortan BC, Mullins GL, Baum D. Am Venous return with knee-chest position and squatting in tetralogy of Fallot. Heart J. 1968 Mar;75(3):313-8.

- ↑ Barnett CH Squatting facets on the European talus J Anat. 1954 October; 88(Pt 4): 509–513.

- ↑ Trinkaus E Squatting among the neandertals: A problem in the behavioral interpretation of skeletal morphology Journal of Archaeological Science Volume 2, Issue 4, December 1975, Pages 327-351

Further reading

Resting position

- Hewes GW: The anthropology of posture Scientific American, 196: 122-132 (1957)

Dynamic exercise

- Escamilla, RF Biodynamics Knee biomechanics of the dynamic squat exercise Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise: January 2001 - Volume 33 - Issue 1 - pp 127–141

Partiution

- Gardosi J., Hutson N Randomised, Controlled Trial Of Squatting In the Second Stage of Labour 1989 The Lancet, Volume 334, Issue 8654, Pages 74–77

- McKay S. Squatting: An Alternate Position For The Second Stage Of Labour Am J Maternal Child Nur 1984;9:181-183.

- Nasir A., Korejo R., Noorani K.J. Child birth in squatting position. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2007/1;57:19-22

- Paciornik M., Paciornik C., Birth in the Squatting Position (1979) Polymorph Films

- Paciornik M., Paciornik C., Commentary: arguments against episiotomy and in favor of squatting for birth. Birth 1990 Dec;17(4):234, 236. and Birth 1991 Jun;18(2):119.

- Paciornik M Use of the squatting position for birth. Birth 1992 Dec;19(4):230-1.

Health effects

- Chakravarty A, Chatterjee S.K., Chakrabarti S. Blood pressure changes during squatting—a study in normal subjects and its possible clinical significance. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2001 Jun; 49(): 678-9

Circulation

- O'Donnell TV, McIlroy MB. The circulatory effects of squatting. Am Heart J. 1962 Sep;64:347-56.

- Sharpey-Schafer EP Effects of Squatting on the Normal and Failing Circulation Br Med J. 12 May 1956; 1(4975): 1072–1074.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crouching. |