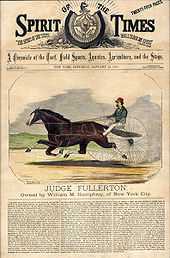

Spirit of the Times

The Spirit of the Times: A Chronicle of the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature and the Stage was an American weekly newspaper published in New York City. The paper aimed for an upper-class readership made up largely of sportsmen. The Spirit also included humorous material, much of it based on experience of settlers near the southwestern frontier.[1] Theatre news was a third important component. The Spirit had an average circulation of about 22,000,[2] with a peak of about 40,000 subscribers.[3]

Life of the paper

William T. Porter and his brothers started the Spirit of the Times in 1831. They sought an upper-class readership, stating in one issue that the Spirit was "designed to promote the views and interests of but an infinitesimal division of those classes of society composing the great mass . . . . "[4] They modeled the paper on Bell's Life in London, a high-class English journal. Subscriptions rose from $2 to $5 in 1836, followed in 1839 by another rise to $10.[5] Editorial policies forbade any discussion of politics in the paper so as to avoid alienating any potential readers. Nevertheless, some writers managed to have material printed that showed favoritism, typically toward the Whigs.[6] The biggest breach of the 'no politics' rule came in 1842, after the publication of Dickens's inflammatory American Notes. A wave of anti-British, anti-imperialist articles followed.[7]

By 1839, the Spirit was the most popular sporting journal in the United States.[8] This allowed the Porters to buy their main rival, the American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine. By 1856, all of the Porter brothers were dead except William. The paper split at some point, one branch called the Spirit of the Times, the other Porter's Spirit of the Times. Porter died in 1858, and circulation of the two papers suffered. After the papers remerged in 1861, George Wilkes bought the enterprise and tried to keep it profitable. In 1878, William B. Curtis became the new editor and helped propagate the journal's elitism by refusing to cover sporting events that were not sanctioned by amateur organizations, which had rigid admission requirements.[8]

Sports writing

By the 1850s, the Spirit covered angling, baseball, cricket, foot racing, fox hunting, horse racing, rowing, and yachting;[9] boxing followed later in the decade. Porter printed all sorts of numbers and statistics, presaging the American sports obsession with such trivia.[9] The paper helped to standardize horse racing by publishing horse weights, suggested betting practices, and offering efficient track management techniques.[8]

Under Wilkes, the Spirit began covering football more extensively than any previous publication. Football coverage in the Spirit quickly outstripped the same in the paper's main rivals, the New York Clipper and the National Police Gazette.[10] The paper covered college games first; in 1882, football got its own section. This coverage expanded again in 1892.

Under Curtis, who was a devotee of speed skating, developments in local and international speed-skating were covered and Curtis compiled lists of skating records. [11]

Theatre writing

The early Spirit covered goings on at all of New York's playhouses. Jacksonian entertainment was stratifying by class, however, and the Spirit quickly relegated most of its coverage to the Park Theatre.[12] Any coverage of the Bowery or Chatham Garden theatres was negative from about 1832 on. Porter wrote in 1840 that the "Bowery, . . . is to be transmogrified into a Circus shortly, the 'Bowery boys' having lost their taste for the illegitimate drama, and they never had any other."[13] He visited the Bowery on a few other occasions, and his reviews on it are full of mockery and derision:

By reasonable computation there were about 300 persons on the stage and wings alone—soldiers in fatigue dresses—officers with side arms—a few jolly tars, and a number of "apple-munching urchins." The scene was indescribably ludicrous. Booth played [Richard III] in his best style, and was really anxious to make a hit, but the confusion incidental to such a crowd on the stage, occasioned constant and most humorous interruptions. It was every thing or any thing, but a tragedy. In the scene with Lady Anne, a scene so much admired for its address, the gallery spectators amused themselves by throwing pennies and silver pieces on the stage, which occasioned an immense scramble among the boys, and they frequently ran between King Richard and Lady Anne, to snatch a stray copper. In the tent scene, so solemn and so impressive, several curious amateurs went up to the table, took up the crown, poised the heavy sword, and examined all the regalia with great care, while Richard was in agony from the terrible dream; and when the scene changed, discovering the ghosts of King Henry, Lady Anne and children, it was difficult to select them from the crowd who thrust their faces and persons among the Royal shadows.

The Battle of Bosworth Field capped the climax—the audience mingled with the soldiers and raced across the stage, to the shouts of the people, the roll of the drums and the bellowing of the trumpets; and when the fight between Richard and Richmond came on, they made a ring round the combattants to see fair play, and kept them at if for nearly a quarter of an hour by "Shrewsberry clock."[14]

Humor writing

William Porter relied on amateur correspondents to cover sporting events across the United States. By the end of the 1830s, these writers had begun to submit fiction as well, including horse-racing fiction, hunting fiction, and tall tales. The paper thus served as an early outlet for many American authors. Among the Spirit's correspondents who would go on to literary careers were George Washington Harris (who used the pseudonyms 'Sugartail' and 'Mr. Free'), Johnson Jones Hooper, Henry Clay Lewis, Alexander McNutt, Thomas Bangs Thorpe, and Jonathan Falconbridge Kelly. Many contributed anonymously, as writing was not always seen as a respectable profession.[15][16]

As these humor segments grew more popular, Porter sought out new writers. Among the humorists he published were Joseph Glover Baldwin, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, and William Tappan Thompson. Many of these writers concentrated on Southwestern humor, that is, humor relating to Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee.[17]

Porter edited two anthologies of the Spirit's humorous contributions. The Big Bear of Arkansas (named for a popular sketch) was published in 1845; A Quarter Race in Kentucky (so titled for the same reason) followed in 1847.

The Spirit's success prompted other papers, such as the New Orleans Picayune and the St. Louis Reveille, to begin running humor pieces in the 1840s.[18] Character types such as the frontiersman and the riverboatsman became common fixtures of American fiction and drama.[17]

Notes

- ↑ Grammer 370.

- ↑ Oriard 289 note 3.

- ↑ Gorn 67.

- ↑ Quoted in Gorn 67.

- ↑ Yates, 31.

- ↑ Flora and MacKethan 845-6.

- ↑ Especially Spirit of the Times, 26 November 1842, 3 December 1842, 4 March 1843.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Sloan 199.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Isenberg 92.

- ↑ Oriard 138.

- ↑ Tebbutt, C.G (1892). "Chapter VII: Modern Racing". Skating. Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 270–272. OL 7132924M. Retrieved Feb 10, 2013.

- ↑ Cockrell 28.

- ↑ 26 September 1840. Spirit of the Times. Quoted in Cockrell 33. Emphasis in the original.

- ↑ Porter, William T. (1 December 1832). Spirit of the Times. Quoted in Cockrell 31-2.

- ↑ Flora and MacKethan 845.

- ↑ Rickels 65.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Flora and MacKethan 350.

- ↑ Flora and MacKethan 931.

References

- Cockrell, Dale (1997). Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World. Cambridge University Press.

- Flora, Joseph M., and MacKethan, Lucinda H., eds. (2002). The Companion to Southern Literature: Themes, Genres, Places, People, Movements, and Motifs. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Gorn, Elliott J., and Goldstein, Warren (1993). A Brief History of American Sports. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Grammer, John M. "Southwestern Humor." In A Companion to the Literature and Culture of the American South, edited by Richard Gray and Owen Robinson, 370-87. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004.

- Isenberg, Michael T. (1988). John L. Sullivan and His America. The University of Illinois Press.

- Porter, William T., ed. The Big Bear of Arkansas and Other Sketches, Illustrative of Characters and Incidents in the South and South-West. Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1845.

- Porter, William T., ed. A Quarter Race in Kentucky and Other Tales: Illustrative of Scenes, Characters, and Incidents, Throughout "The Universal Yankee Nation". Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1847.

- Rickels, Milton. George Washington Harris. New York: Twayne, 1965.

- Oriard, Michael (1993). Reading Football: How the Popular Press Created an American Spectacle. University of North Carolina Press.

- Sloan, W. David, and Parcell, Lisa Mullikin, eds. (2002). American Journalism: History, Principles, Practices. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

- Yates, Norris W. William T. Porter and the Spirit of the Times: A Study of the Big Bear School of Humor. Baton Rouge: University of Louisiana Press, 1957.

- Wildwood, Will (Fred Pond) (Fall 1985). "Memoirs of Eminent Sportsman:Genio C. Scott". The American Fly Fisher (Manchester, VT: American Museum of Fly Fishing) 12 (4): 23–26. Retrieved 2014-11-19.