Spin magnetic moment

In physics, mainly quantum mechanics and particle physics, a spin magnetic moment is the magnetic moment induced by the spin of elementary particles. For example the electron is an elementary spin-1/2 fermion. Quantum electrodynamics gives the most accurate prediction of the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron.

"Spin" is a non–classical property of elementary particles, since classically the "spin angular momentum" of a material object is really just the total orbital angular momenta of the object's constituents about the rotation axis. Elementary particles are conceived as concepts which have no axis to "spin" around (see wave-particle duality).

In general, a magnetic moment can be defined in terms of an electric current and the area enclosed by the current loop. Since angular momentum corresponds to rotational motion, the magnetic moment can be related to the orbital angular momentum of the charge carriers in the constituting the current. However, in magnetic materials, the atomic and molecular dipoles have magnetic moments not just because of their quantized orbital angular momentum, but the spin of elementary particles constituting them (electrons, and the quarks in the protons and neutrons of the atomic nuclei). A particle may have a spin magnetic moment without having an electric charge; the neutron is electrically neutral but has a non–zero magnetic moment, because of its internal quark structure.

Calculation

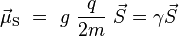

We can calculate the observable spin magnetic moment, a vector, μ→S, for a sub-atomic particle with charge q, mass m, and spin angular momentum (also a vector), S→, via:[n 1]

-

(1)

where  is the gyromagnetic ratio, g is a dimensionless number, called the g-factor, q is the charge, and m is the mass. The g-factor depends on the particle: it is g = −2.0023 for the electron, g = 5.586 for the proton, and g = −3.826 for the neutron. The proton and neutron are composed of quarks, which have a non-zero charge and a spin of ħ/2, and this must be taken into account when calculating their g-factors. Even though the neutron has a charge q = 0, its quarks give it a magnetic moment. The proton and electron's spin magnetic moments can be calculated by setting q = +e and q = −e, respectively, where e is the elementary charge.

is the gyromagnetic ratio, g is a dimensionless number, called the g-factor, q is the charge, and m is the mass. The g-factor depends on the particle: it is g = −2.0023 for the electron, g = 5.586 for the proton, and g = −3.826 for the neutron. The proton and neutron are composed of quarks, which have a non-zero charge and a spin of ħ/2, and this must be taken into account when calculating their g-factors. Even though the neutron has a charge q = 0, its quarks give it a magnetic moment. The proton and electron's spin magnetic moments can be calculated by setting q = +e and q = −e, respectively, where e is the elementary charge.

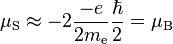

The intrinsic electron magnetic dipole moment is approximately equal to the Bohr magneton μB because g ≈ −2 and the electron's spin is also ħ/2:

-

(2)

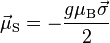

Equation (1) is therefore normally written as[n 2]

-

(3)

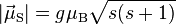

Just like the total spin angular momentum cannot be measured, neither can the total spin magnetic moment be measured. Equations (1), (2), (3) give the physical observable, that component of the magnetic moment measured along an axis, relative to or along the applied field direction. Assuming a Cartesian coordinate system, conventionally, the z-axis is chosen but the observable values of the component of spin angular momentum along all three axes are each ±ħ/2. However, in order to obtain the magnitude of the total spin angular momentum, S→ be replaced by its eigenvalue, √s(s + 1), where s is the spin quantum number. In turn, calculation of the magnitude of the total spin magnetic moment requires that (3) be replaced by:

-

(4)

Thus, for a single electron, with spin quantum number s = 1/2, the component of the magnetic moment along the field direction is, from (3), |μ→S,z| = μB, while the (magnitude of the) total spin magnetic moment is, from (4), |μ→S| = √3 μB, or approximately 1.73 Bohr magnetons.

The analysis is readily extended to the spin-only magnetic moment of an atom. For example, the total spin magnetic moment (sometimes referred to as the effective magnetic moment when the orbital moment contribution to the total magnetic moment is neglected) of a transition metal ion with a single d shell electron outside of closed shells (e.g. Titanium Ti3+) is 1.73 μB since s = 1/2, while an atom with two unpaired electrons (e.g. Vanadium V3+) with S = 1 would have an effective magnetic moment of 2.83 μB.

Spin in chemistry

Spin magnetic moments create a basis for one of the most important principles in chemistry, the Pauli exclusion principle. This principle, first suggested by Wolfgang Pauli, governs most of modern-day chemistry. The theory plays further roles than just the explanations of doublets within electromagnetic spectrum. This additional quantum number, spin, became the basis for the modern standard model used today, which includes the use of Hund's rules, and an explanation of beta decay.

History

The idea of a spin angular momentum was first proposed in a 1925 publication by George Uhlenbeck and Samuel Goudsmit to explain hyperfine splitting in atomic spectra.[n 3] In 1928, Paul Dirac provided a rigorous theoretical foundation for the concept in the Dirac equation for the wavefunction of the electron.[n 4] In 2014, Edward Lee of the University of Wisconsin-Madison developed a simple model that can accurately predict the voting outcomes of the US Supreme Court, where each judge is treated as a magnetic spin.[1]

Notes

- ↑ Y. Peleg, R. Pnini, E. Zaarur, E. Hecht (2010). Quantum Mechanics. Shaum's outlines (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 181. ISBN 9-780071-623582.

- ↑ R. Resnick, R. Eisberg (1985). Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei and Particles (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-471-87373-0.

- ↑ Earlier the same year, Ralph Kronig discussed the idea with Wolfgang Pauli, but Pauli criticized the idea so severely that Kronig decided not to publish it.(Scerri 1995)

- ↑ (Dirac 1928)

See also

- Nuclear magneton

- Pauli principle

- Nuclear magnetic resonance

- Multipole expansion

- Relativistic quantum mechanics

References

- ↑ Tushna Commissariat (March 4, 2014). "Magnetic supreme court judges, easier visa access, visualizing arXiv and more". Blog – physicsworld.com. Physics World.

This entry was posted in American Physical Society [APS] March Meeting 2014 and tagged complex systems, modelling, science and society, visas. Permalinked.

Selected books

- B. R. Martin, G.Shaw. Particle Physics (3rd ed.). Manchester Physics Series, John Wiley & Sons. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-470-03294-7.

- Bransden, BH; Joachain, CJ (1983). Physics of Atoms and Molecules (1st ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 631. ISBN 0-582-44401-2.

- P.W. Atkins (1974). Quanta: A handbook of concepts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855493-1.

- E. Merzbacher (1998). Quantum Mechanics (3rd ed.). ISBN 0-471-887-021.

- P.W. Atkins (1977). Molecular Quantum Mechanics Parts I and II: An Introduction to Quantum Chemistry 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855129-0.

- P.W. Atkins (1977). Molecular Quantum Mechanics Part III: An Introduction to Quantum Chemistry 2. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855130-4.

- R. Resnick, R. Eisberg (1985). Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei and Particles (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-87373-0.

- Sin-Itiro Tomonaga (1997). The Story of Spin. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226807942.

Selected papers

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1928-02-01). "The Quantum Theory of the Electron". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 117 (778): 610–624. Bibcode:1928RSPSA.117..610D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1928.0023.

- Scerri, Eric R. (1995). "The exclusion principle, chemistry and hidden variables". Synthese 102 (1): 165–169. doi:10.1007/BF01063903.

External links

- An Introduction to the Electronic Structure of Atoms and Molecules by Dr. Richard F.W. Bader (McMaster University)