Spin-½

In quantum mechanics, spin is an intrinsic property of all elementary particles. Fermions, the particles that constitute ordinary matter, have half-integer spin. Spin-½ particles constitute an important subset of such fermions. All known elementary fermions have a spin of ½.[1][2][3]

Overview

Particles having net spin ½ include the proton, neutron, electron, neutrino, and quarks. The dynamics of spin-½ objects cannot be accurately described using classical physics; they are among the simplest systems which require quantum mechanics to describe them. As such, the study of the behavior of spin-½ systems forms a central part of quantum mechanics.

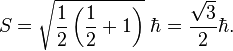

A spin-½ particle is characterized by an angular momentum quantum number for spin s of 1/2. In solutions of the Schrödinger equation, angular momentum is quantized according to this number, so that total spin angular momentum

However, the observed fine structure when the electron is observed along one axis, such as the Z-axis, is quantized in terms of a magnetic quantum number, which can be viewed as a quantization of a vector component of this total angular momentum, which can have only the values of ±½ħ.

Note that these values for angular momentum are functions only of the reduced Planck constant (the angular momentum of any photon), with no dependence on mass or charge.[4]

Stern–Gerlach experiment

The necessity of introducing half-integral spin goes back experimentally to the results of the Stern–Gerlach experiment. A beam of atoms is run through a strong heterogeneous magnetic field, which then splits into N parts depending on the intrinsic angular momentum of the atoms. It was found that for silver atoms, the beam was split in two—the ground state therefore could not be integral, because even if the intrinsic angular momentum of the atoms were as small as possible, 1, the beam would be split into 3 parts, corresponding to atoms with Lz = −1, 0, and +1. The conclusion was that silver atoms had net intrinsic angular momentum of 1⁄2.[1]

General properties

Spin-½ objects are all fermions (a fact explained by the spin statistics theorem) and satisfy the Pauli exclusion principle. Spin-½ particles can have a permanent magnetic moment along the direction of their spin, and this magnetic moment gives rise to electromagnetic interactions that depend on the spin. One such effect that was important in the discovery of spin is the Zeeman effect, the splitting of a spectral line into several components in the presence of a static magnetic field.

Unlike in more complicated quantum mechanical systems, the spin of a spin-½ particle can be expressed as a linear combination of just two eigenstates, or eigenspinors. These are traditionally labeled spin up and spin down. Because of this the quantum mechanical spin operators can be represented as simple 2 × 2 matrices. These matrices are called the Pauli matrices.

Creation and annihilation operators can be constructed for spin-½ objects; these obey the same commutation relations as other angular momentum operators.

Connection to the uncertainty principle

One consequence of the generalized uncertainty principle is that the spin projection operators (which measure the spin along a given direction like x, y, or z), cannot be measured simultaneously. Physically, this means that it is ill defined what axis a particle is spinning about. A measurement of the z-component of spin destroys any information about the x and y components that might previously have been obtained.

Complex Phase

.gif)

Mathematically, quantum mechanical spin is not described by a vector as in classical angular momentum. It is described by a complex-valued vector with two components called a spinor. There are subtle differences between the behavior of spinors and vectors under coordinate rotations, stemming from the behavior of a vector space over a complex field.

When a spinor is rotated by 360 degrees (one full turn), it becomes negative, then after a further rotation 360 degrees becomes positive again. This comes about because in quantum theory the state of a particle or system is represented by a complex probability amplitude (wavefunction) Ψ, and when the system is measured; the probability of finding the system in the state Ψ equals |Ψ|2 = Ψ*Ψ, the square of absolute value of the amplitude.

Suppose a detector, that can be rotated, measures a particle, in which the probabilities of detecting some state are affected by the rotation of the detector. When the system is rotated through 360 degrees the observed output and physics are the same as initially but the amplitudes are changed for a spin-½ particle by a factor of −1 or a phase shift of half of 360 degrees. When the probabilities are calculated the −1 is squared; (−1)2 = 1, so the predicted physics is same as in the starting position. Also in a spin-½ particle there are only two spin states and the amplitudes for both change by the same −1 factor so the interference effects are identical, unlike the case for higher spins. The complex probability amplitudes are something of a theoretical construct and cannot be directly observed.

If the probability amplitudes rotated by the same amount as the detector, then they would have changed by a factor of −1 when the equipment was rotated by 180 degrees, which when squared would predict the same output as at the start but this is wrong experimentally. If the detector is rotated by 180 degrees, the result with spin-½ particles can be different to what it would be if not rotated, hence the factor of a half is necessary to make the predictions of the theory match experiment.

Mathematical description

NRQM (Non-relativistic quantum mechanics)

The quantum state of a spin-½ particle can be described by a complex-valued vector with two components called, a spinor. Observable states of the particle are then found by the spin-operators, Sx, Sy, and Sz, and the total spin operator, S.

Observables

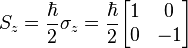

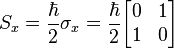

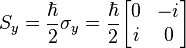

When spinors are used to describe the quantum states, the three spin operators (Sx, Sy, Sz,) can described by 2x2 matrices called the Pauli matrices whose eigenvalues are ±ħ/2.

For example, the spin projection operator Sz affects a measurement of the spin in the z direction.

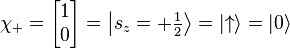

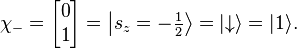

The two eigenvalues of Sz, ±ħ/2, then correspond to the following eigenspinors:

These vectors form a complete basis for the Hilbert space describing the spin-½ particle. Thus, linear combinations of these two states can represent all possible states of the spin, including in the x and y directions.

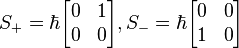

The ladder operators are:

Since S±=Sx±iSy, Sx=1/2(S++S-), and Sy=1/2i(S+-S-). Thus:

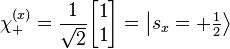

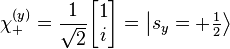

Their normalized eigenspinors can be found in the usual way. For Sx, they are:

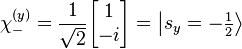

For Sy, they are:

RQM (relativistic )

While NRQM defines spin-½ with 2 dimensions in Hilbert space with dynamics that are described in 3-dimensional space and time, RQM define the spin with 4 dimensions in Hilbert space and dynamics described by 4-dimensional space-time.

Observables

As a consequence of the four-dimensional nature of space-time in relativity, relativistic quantum mechanics uses 4x4 matrices to describe spin operators and observables.

Spin as a consequence of combining quantum theory and special relativity

When physicist Paul Dirac tried to modify the Schrödinger equation so that it was consistent with Einstein's theory of relativity, he found it was only possible by including matrices in the resulting Dirac Equation, implying the wave must have multiple components leading to spin.[5]

See also

- Spin

- Spinor

- Fermions

- Pauli matrices

- Spin-statistics theorem relating spin-1/2 and fermionic statistics

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei and Particles (2nd Edition), R. Resnick, R. Eisberg, John Wiley & Sons, 1985, ISBN 978-0-471-87373-0

- ↑ Quanta: A handbook of concepts, P.W. Atkins, Oxford University Press, 1974, ISBN 0-19-855493-1

- ↑ Peleg, Y.; Pnini, R.; Zaarur, E.; Hecht, E. (2010). Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-071-62358-2.

- ↑ C.R. Nave (2005). "Electron Spin". Georgia State University. and internal links from the first section therein.

- ↑ Quantum Field Theory, D. McMahon, Mc Graw Hill (USA), 2008, ISBN 978-0-07-154382-8

Further reading

- Griffiths, David J. (2005) Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-111892-7.

- Feynman Lectures on Physics Volume 3 Chapter 6

- Penrose, Roger (2007). The Road to Reality. Vintage books. ISBN 0-679-77631-1.