Speech-to-song effect

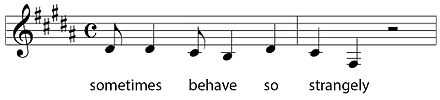

The Speech-to-Song Illusion was discovered by Diana Deutsch in 1995. She was fine-tuning her spoken commentary at the beginning of her CD "Musical Illusions and Paradoxes".[1] In the process, she had put the phrase ‘sometimes behave so strangely’ on a loop, and she noticed that after it had been repeated several times it sounded as though it was sung rather than spoken. As a further twist, she noted that when the original sentence containing this phrase was again played, it began by sounding like normal speech, but when it came to the phrase that had been repeated, it appeared to burst into song. Deutsch later included this illusion in her CD "Phantom Words and Other Curiosities".[2]

Experiments

Deutsch, Henthorn and Lapidis[3][4] showed that in order for the illusion to occur, the phrase needs to be repeated exactly; repeating the phrase under transposition or with the words in jumbled orderings did not cause it to be heard as sung. They also created sound demonstrations showing how subjects repeat back the phrase after it had been repeated ten times (it is obviously being sung) and after it has been presented only once (it is obviously being spoken).

Falk and Rathke[5] showed that the speech-to-song illusion can occur when German subjects listened to German sentences as well. These authors also showed that certain physical properties of the acoustic signal facilitated the development of the illusion. Later, Vanden Bosch Der Nederlanden[6] replicated the findings of Deutsch et al., and showed that the illusion is obtained both by people who are musically trained and also by those who are untrained. She also confirmed that transposing the repeating phrase reduced the transformation effect. In addition she found that altering the temporal characteristics of the repeating phrase did not affect the illusion. Tierney, Dick, Deutsch, and Sereno[7] explored the neuroanatomical underpinnings of the illusion. They employed a corpus of spoken phrases that came to be heard as sung rather than spoken following several repetitions, and also a matched corpus of spoken phrases that continued to be heard as spoken following the same amount of repetition. Subjects listened to these phrases while their brains were being scanned using fMRI, and found that a network of regions, particularly in the temporal lobe, responded more strongly to the speech that was heard as sung. This network overlapped with regions that were previously associated with pitch perception and song production.

Implications

Elizabeth Margulis, in her book "On Repeat"[8] discusses the speech-to-song illusion in detail, and argues that a strong reason for the perceptual shift from speech to song is that repetition is a fundamental characteristic of music, though not of speech. Repeating the spoken phrase therefore causes the listener to transform it perceptually so that it is heard as sung rather than spoken.

In general, there is an ongoing debate concerning whether speech and music are subserved by separate modules[9] or by largely overlapping neural circuitry.[10][11] In discussing this issue it is usually assumed that whether a phrase is perceived as spoken or sung depends on its physical characteristics. Further, studies comparing perception of speech and music generally employ signals that differ in their acoustic characteristics, which makes the interpretation of the findings difficult. The speech-to-song illusion overcomes these difficulties since here a spoken phrase is perceptually transformed so that it is heard as sung rather than spoken without altering the signal in any way, or providing any context, but simply by repeating it. The illusion therefore indicates that the brain mechanisms underlying perception of speech and song accept the same input but process it differently so as to give rise to different percepts.

See also

References

- ↑ Deutsch, D. (1995). Musical Illusions and Paradoxes. Philomel Records. OCLC 36640949. ASIN 1377600017

- ↑ Deutsch, D. (2003). Phantom Words and Other Curiosities. Philomel Records. OCLC 54342787. ASIN 1377600025

- ↑ Deutsch, D.; Lapidis, R.; Henthorn, T. (2008). "The Speech-to-Song Illusion". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 124: 2471. doi:10.1121/1.4808987.

- ↑ Deutsch, D.; Henthorn, T.; Lapidis, R. (2011). "Illusory transformation from speech to song" (PDF). Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 129: 2245–2252. doi:10.1121/1.3562174.

- ↑ Falk, S.; Rathke, T. (2010). On the Speech-To-Song Illusion: Evidence from German (PDF). Speech Prosody 2010 Conference Proceedings.

- ↑ Vanden Bosch Der Nederlanden, C. M. (2013). The role of music-specific representations when processing speech: Using a musical illusion to elucidate domain-specific and –general processes (Thesis).

- ↑ Tierney, A.; Dick, F.; Deutsch, D.; Sereno, M. (2012). "Speech versus Song: Multiple Pitch-Sensitive Areas Revealed by a Naturally Occurring Musical Illusion" (PDF). Cerebral Cortex 23 (2): 249–254. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhs003. ISSN 1047-3211.

- ↑ Margulis, E. H. (2013). "On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind.". doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199990825.001.0001.

- ↑ Peretz, I.; Coltheart, M. (2003). "Modularity of music processing". Nature Neuroscience 6 (7): 688–691. doi:10.1038/nn1083. ISSN 1097-6256.

- ↑ Patel, A. D. (1999). Music, Language, and the Brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-12-213565-1.

- ↑ Koelsch, S. (2011). "Toward a Neural Basis of Music Perception – A Review and Updated Model". Frontier in Psychology 2. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00110. ISSN 1664-1078.