Specialist schools programme

The specialist schools programme was a UK government initiative which encouraged secondary schools in England to specialise in certain areas of the curriculum to boost achievement. The Specialist Schools and Academies Trust was responsible for the delivery of the programme. At the end of the status there were nearly 3,000 specialist schools, which was fully 88% of the state-funded secondary schools in England.[1] When the new Coalition government took power in May 2010 the scheme was ended and funding was absorbed into general school budgets.[2]

History

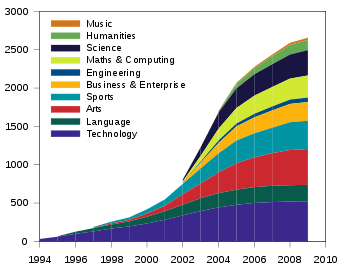

The Education Reform Act 1988 introduced a new compulsory subject of Technology, but there were insufficient funds to equip all schools to teach the subject. A first attempt at developing centres of excellence, the City Technology College programme between 1988 and 1993, had produced only 15 schools. In 1994, the Conservative government, at the urging of Sir Cyril Taylor, designated 35 grant-maintained and voluntary aided schools as Technology Colleges. The schools were required to arrange private sponsorship of £100,000, and would then receive a matching government capital grant and increased recurrent funding. The following year the programme was opened to all maintained schools, and specialism in Languages was added. Specialisms in Arts and Sport were added in 1996.[3][4][5][6]

As specialism implied diversity of schools, it was opposed by many supporters of comprehensive schools, including many in the Labour Party. Nevertheless, in 1997 the new Labour government, also encouraged by Sir Cyril Taylor, adopted the embryonic programme, and the number of specialist schools continued to grow.[3][6] The School Standards and Framework Act 1998 made it possible for specialist schools to select up to 10% of their intake on aptitude in the existing specialisms in sport, the arts, modern languages and technology, though new selection for aptitude in technology was prohibited in 2008.[7] However few have taken up this option.[8]

The 2001 white paper Schools Achieving Success envisaged expansion of the programme to 50% of secondary schools by 2005, and introduced new specialisms in Business and Enterprise, Engineering, Mathematics and Computing and Science.[9] The emphasis was shifting from centres of excellence to a means of driving up standards in most schools. The required amount of private sponsorship was halved, and could be made up of goods and services in lieu of cash.[3][6] Software donations had been ineligible due to the difficulty in evaluating the true value of something that has no manufacturing cost and can simply be given away as a form of collateral, but this changed when Oracle and then Microsoft were allowed to sponsor the programme with "in kind" donations.[10] In 2002 the government introduced the Partnership Fund, funded at £3 million per annum, to make up the shortfall for schools that were unable to raise the required £50,000 of private sponsorship.[5] Specialisms in Humanities and Music were added in 2004. By 2008 approximately 90% of maintained secondary schools had become specialist schools.[6]

Extension of the specialist programme to primary schools is being trialled at 34 schools in England, starting in 2007. The specialisms involved in the pilot are Arts, Music, Languages, Science and Physical Education/Sport.[4] A specialist schools programme has been trialled by the Department of Education of Northern Ireland from 2006, with 44 schools being awarded the status by September 2009.[11][12]

Gaining specialist school status

To apply for specialist school status, a school must demonstrate reasonable standards of achievement, and produce a four-year development plan with quantified targets related to learning outcomes. The school must also raise £50,000 in private sector sponsorship.[2][3] Private sector sponsorship includes charitable trusts, internal fund raising and donations from private companies. In some cases donations can be made in cash from entities in the private sector such as Arcadia and HSBC, but may also be donations "in kind" of goods or services. The total sponsorship to date is of the order of £100m.

A school may specialise in any of the following fields, or combine specialisms in two of them (at the same level of funding):[2][4]

- Arts (can be Media, Performing Arts, Visual Arts, or combination of these)

- Business & Enterprise

- Engineering

- Humanities

- Languages

- Mathematics & Computing

- Music

- Science

- Sports

- Technology

Specialist schools must still meet the full requirements of the English national curriculum, so the specialism is seen as adding value to the existing statutory provision rather than being a radical departure from it. The important aspect in the eyes of the government is the focus that the specialism provides for providing leadership in the quest for whole school improvement.[4]

The reward for achieving specialist status is a government grant of £100,000 to go with the £50,000 in sponsorship for a capital project related to the specialism and an extra £129 per pupil per year for four years to support the development plan. This is normally targeted on additional staffing and professional development, though up to 30% may be spent on equipment.[2][4][6]

Schools that make a good attempt at achieving their targets over the 4 year development plan period normally have their grants renewed at 3-year intervals with no further need to raise sponsorship. However since 2008, the government has sought to encourage long-term relationships with business partners by offering a matching grant to redesignating specialist schools that are able to raise a further £25,000 in private sponsorship.

High Performing Specialist Status

Some schools that demonstrated that they were achieving significantly higher results than other schools were invited to apply to be designated as High Performing Specialist Schools. This typically allowed the school to apply for a further specialism, which brought with it additional funding so that the school could develop that further specialism.[2] By 2009 some 900 schools (30% of specialist schools) had achieved this status.[4]

Evaluation

Results

David Jesson of the University of York published a series of annual studies of the results of the specialist schools program, on behalf of the SSAT. These studies reported that non-selective specialist schools achieved significantly higher results at GCSE results than non-specialist comprehensive schools, that they achieved higher 'added value' when prior achievement was taken into account, and that the gains had increased with the length of time the school had been specialist.[13][14][15][16] Jesson's statistical methodology was criticised,[17] and others pointed out that early specialist schools were chosen for the programme because they were already successful.[6] Other studies found that specialist schools performed slightly better at GCSE, particularly benefitting more able pupils and narrowing the gap between boys and girls.[3][18][19][20] Subsequent studies attributed the increase to the additional funding,[21][22] and reported that the effect was diminishing as a greater proportion of schools become specialist.[23]

Systemic effects

Specialist schools and academies were promoted, notably by Estelle Morris (Education Secretary 2001–2002), as part of an attempt to improve standards by 'increasing diversity' in secondary schools.[24] Left wing commentators had criticised this move away from the comprehensive ideal.[25] The two biggest UK teaching unions had opposed the programme because they said that it created a two-tier education system, made up of specialist schools with extra funding and non-specialist schools which could not have benefited from any extra money.[26]

There was also evidence that specialist schools took fewer children from poorer families than non-specialist schools.[5] One possible cause was that it may have be easier for middle-class parents to raise the necessary sponsorship.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Specialist Schools". The Standards Site. Department for Children, Schools and Families. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Specialist Schools Guidance". The Standards Site. Department for Children, Schools and Families. 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Schagen, Sandie; Davies, Deborah; Rudd, Peter; Schagen, Ian (February 2002). The Impact of Specialist and Faith Schools on Performance. Slough: National Foundation for Education Research. LGA Research Report 28.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Specialist schools: A briefing paper for section 5 inspections. Office for Standards in Education. September 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Castle, Frances; Evans, Jennifer (February 2006). Specialist Schools – what do we know?. Research and Information on State Education. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Smithers, Alan; Robinson, Pamela (2009). Specialist science schools. Centre for Education and Employment Research, University of Buckingham.

- ↑ "School admissions and appeals". Department for Children, Schools and Families. 10 February 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ↑ Specialist Schools: An evaluation of progress. Office for Standards in Education. October 2001. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ↑ Schools Achieving Success. Department for Education and Skills. 2001.

- ↑ "Charles Clarke welcomes new partnership with Oracle to sponsor specialist schools" (Press release). Department for Education and Skills. 23 June 2003.

- ↑ "Specialist Schools Programme". Department of Education (Northern Ireland). Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ↑ "Specialist Humanities Academy". Slemish College. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ↑ Jesson, David; Taylor, Cyril (2003). Educational outcomes and value added by specialist schools: 2002 Analysis. Specialist Schools and Academies Trust.

- ↑ "Specialist schools outperform non-specialist in all areas and academies top value added chart" (Press release). Specialist Schools and Academies Trust. 7 April 2006. Archived from the original on 26 September 2006.

- ↑ Jesson, David; Crossley, David (2007). Educational outcomes and value added by specialist schools: 2006 Analysis. Specialist Schools and Academies Trust.

- ↑ Revell, Phil (11 July 2002). "Class Distinctions". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Schagen, Ian; Goldstein, Harvey (2002). "Do specialist schools add value? Some methodological problems". Research Intelligence 80: 12–15. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ↑ Levacic, Rosalind; Jenkins, Andrew (September 2004). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Specialist Schools. Centre for the Economics of Education, London School of Economics and Political Science. ISBN 0-7530-1732-6. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ↑ "Specialist schools 'succeeding'". BBC News. 16 February 2005. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ↑ A Study of the Specialist Schools Programme. Department for Education and Skills. 2004. ISBN 1-84478-330-8. DfES Research Report RR587. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ↑ Mangan, Jean; Pugh, Geoff; Gray, John (31 December 2006). "Examination Performance and School Expenditure in English Secondary Schools in a Dynamic Setting". IEPR Working Paper 34.

- ↑ "Specialist schools 'not better'". BBC News. 7 September 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ↑ Pugh, Geoff; Mangan, Jean; Gray, John (October 2008). Resources and Attainment at Key Stage 4: Estimates from a Dynamic Methodology. Department for Children, Schools and Families. ISBN 978-1-84775-253-6. DCSF-RB056.

- ↑ "Estelle Morris speech on secondary education (full text)". Local Government Chronicle. 25 June 2002. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ↑ Toynbee, Polly (6 December 2002). "Lessons in class warfare". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ↑ Parkinson, Justin (28 March 2005). "Specialist schools 'limit choice'". BBC News. Retrieved 15 December 2008.