Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

| Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

|---|---|

|

Seal of the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives | |

|

Flag of the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives | |

| Style |

Mr. Speaker (Informal and within the House) The Honorable (Formal) |

| Appointer |

U.S. House of Representatives (Elected by) |

| Term length | No term limits are imposed; elected by the House at the start of each session, and upon a vacancy |

| Constituting instrument | U.S. Constitution |

| Formation | March 4, 1789 |

| First holder |

Frederick Muhlenberg April 1, 1789 |

| Succession | Second in the Presidential Line of Succession |

| Website | Speaker of the House John Boehner |

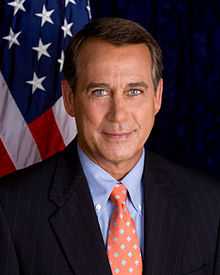

The Speaker of the House is the presiding officer of the chamber. The office was established in 1789 by Article I, Section 2 of the United States Constitution, which states in part, "The House of Representatives shall choose their Speaker..." The current Speaker is John Boehner, a Republican who represents Ohio's 8th congressional district. The Constitution does not require that the Speaker be an elected House Representative, though all Speakers have been an elected Member of Congress.[1]

The Speaker is second in the United States presidential line of succession, after the Vice President and ahead of the President pro tempore of the U.S. Senate.[2] Unlike some Westminster system parliaments, in which the office of Speaker is considered non-partisan, in the United States, the Speaker of the House is a leadership position and the office-holder actively works to set the majority party's legislative agenda. The Speaker usually does not personally preside over debates, instead delegating the duty to members of the House from the majority party. The Speaker usually does not participate in debate and rarely votes.

Aside from duties relating to heading the House and the majority political party, the Speaker also performs administrative and procedural functions, and represents his or her Congressional district.

Selection

The House of Representatives elects the Speaker of the House on the first day of every new Congress and in the event of the death or resignation of an incumbent Speaker. The Clerk of the House of Representatives requests nominations: there are normally two, one from each major party (each party having previously met to decide on its nominee). The Clerk then calls the roll of the Representatives-elect, each Representative-elect indicating the surname of the candidate he or she is supporting. Representatives-elect are not restricted to voting for one of the nominated candidates and may vote for any person, even for someone who is not a member (or member-elect) of the House at all. They may also abstain by voting "present".[3]

To be elected as Speaker, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all votes cast for individuals, i.e. excluding those who abstain. If no candidate wins such a majority, then the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. The last time repeated votes were required was in 1923, when the Speaker was elected on the ninth ballot.[3]

The new Speaker is then sworn in by the Dean of the United States House of Representatives, the chamber's longest-serving member.

In modern practice, the Speaker is chosen by the majority party from among its senior leaders either when a vacancy in the office arrives or when the majority party changes. It is usually obvious within two or three weeks of a House election who the new Speaker will be. Previous Speakers have been minority leaders (when the majority party changes, as they are already the House party leader, and as the minority leader are usually their party's nominee for Speaker), or majority leaders (upon departure of the current Speaker in the majority party), assuming that the party leadership hierarchy is followed. In the past, other candidates have included chairpersons of influential standing committees.

So far, the Democrats have always elevated their minority leader to the Speakership upon reclaiming majority control of the House. However, Republicans have not always followed this leadership succession pattern. In 1919, Republicans bypassed James Robert Mann, R-IL, who had been Minority Leader for eight years, and elected a backbencher representative, Frederick H. Gillett, R-MA, to be Speaker. Mann had "angered many Republicans by objecting to their private bills on the floor" and was also a protégé of autocratic Speaker Joseph Cannon, R-IL (1903–1911), and many members "suspected that he would try to re-centralize power in his hands if elected Speaker."[4] More recently, although Robert H. Michel was Minority Leader in 1994 when the Republicans regained control of the House in the 1994 midterm elections, he had already announced his retirement and had little or no involvement in the campaign. Including the "Contract with America", which was unveiled six weeks before Election Day. Michel opted not to seek re-election because he had been isolated in the caucus by Minority Whip Newt Gingrich and other younger and more aggressive Congressmen.

It is expected that members of the House vote for their party's candidate. If they do not, they usually vote for someone else in their party or vote "present". Those who vote for the other party's candidate often face serious consequences, up to and including the loss of seniority. The last instance where a representative voted for the other party's candidate was in 2000, when Democrat Jim Traficant of Ohio voted for Republican Dennis Hastert. In response, the Democrats stripped him of his seniority and he lost all of his committee posts.

If the Speaker's party loses control of the House in an election, and if the Speaker and Majority Leader both remain in the leadership hierarchy, they would become the Minority Leader and Minority Whip, respectively. As the minority party has one less leadership position after losing the Speaker's chair, there may be a contest for the remaining leadership positions. Most Speakers whose party has lost control of the House have not returned to the party leadership (Tom Foley lost his seat, Dennis Hastert returned to the backbenches and resigned from the House in late 2007). However, Speakers Joseph William Martin, Jr. and Sam Rayburn did seek the post of Minority Leader in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Nancy Pelosi is the most recent example of an outgoing Speaker who was elected Minority Leader, after the Democrats lost control of the House in the 2010 elections.

History

The first Speaker was Frederick Muhlenberg, who was elected as a Federalist for the first four Congresses.[5]

The position of Speaker started to gain its partisan role and its power in legislative development under Henry Clay (1811–1814, 1815–1820, and 1823–1825).[6] In contrast to many of his predecessors, Clay participated in several debates, and used his influence to procure the passage of measures he supported—for instance, the declaration of the War of 1812, and various laws relating to Clay's "American System". Furthermore, when no candidate received an Electoral College majority in the 1824 presidential election causing the President to be elected by the House, Speaker Clay threw his support to John Quincy Adams instead of Andrew Jackson, thereby ensuring Adams' victory. Following Clay's retirement in 1825, the power of the Speakership once again began to decline, despite Speakership elections becoming increasingly bitter. As the Civil War approached, several sectional factions nominated their own candidates, often making it difficult for any candidate to attain a majority. In 1855 and again in 1859, for example, the contest for Speaker lasted for two months before the House achieved a result. During this time, Speakers tended to have very short tenures. For example, from 1839 to 1863 there were eleven Speakers, only one of whom served for more than one term. To date, James K. Polk is the only Speaker of the House later elected President of the United States.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the office of Speaker began to develop into a very powerful one. At the time, one of the most important sources of the Speaker's power was his position as Chairman of the Committee on Rules, which, after the reorganization of the committee system in 1880, became one of the most powerful standing committees of the House. Furthermore, several Speakers became leading figures in their political parties; examples include Democrats Samuel J. Randall, John Griffin Carlisle, and Charles F. Crisp, and Republicans James G. Blaine, Thomas Brackett Reed, and Joseph Gurney Cannon.

The power of the Speaker was greatly augmented during the tenure of the Republican Thomas Brackett Reed (1889–1891, 1895–1899). "Czar Reed", as he was called by his opponents,[7] sought to end the obstruction of bills by the minority, in particular by countering the tactic known as the "disappearing quorum".[8] By refusing to vote on a motion, the minority could ensure that a quorum would not be achieved, and that the result would be invalid. Reed, however, declared that members who were in the chamber but refused to vote would still count for the purposes of determining a quorum. Through these and other rulings, Reed ensured that the Democrats could not block the Republican agenda.

The Speakership reached its apogee during the term of Republican Joseph Gurney Cannon (1903–1911). Cannon exercised extraordinary control over the legislative process. He determined the agenda of the House, appointed the members of all committees, chose committee chairmen, headed the Rules Committee, and determined which committee heard each bill. He vigorously used his powers to ensure that Republican proposals were passed by the House. In 1910, however, Democrats and several dissatisfied Republicans joined together to strip Cannon of many of his powers, including the ability to name committee members and his chairmanship of the Rules Committee.[9] Fifteen years later, Speaker Nicholas Longworth restored much, but not all, of the lost influence of the position.

One of the most influential Speakers in history was Democrat Sam Rayburn.[10] Rayburn was the longest-serving Speaker in history, holding office from 1940 to 1947, 1949 to 1953, and 1955 to 1961. He helped shape many bills, working quietly in the background with House committees. He also helped ensure the passage of several domestic measures and foreign assistance programs advocated by Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman. Rayburn's successor, Democrat John William McCormack (served 1962–1971), was a somewhat less influential speaker, particularly because of dissent from younger members of the Democratic Party. During the mid-1970s, the power of the Speakership once again grew under Democrat Carl Albert. The Committee on Rules ceased to be a semi-independent panel, as it had been since 1910. Instead, it once again became an arm of the party leadership. Moreover, in 1975, the Speaker was granted the authority to appoint a majority of the members of the Rules Committee. Meanwhile, the power of committee chairmen was curtailed, further increasing the relative influence of the Speaker.

Albert's successor, Democrat Tip O'Neill, was a prominent Speaker because of his public opposition to the policies of President Ronald Reagan. O'Neill is the longest continually serving Speaker, from 1977 through 1987. He challenged Reagan on domestic programs and on defense expenditures. Republicans made O'Neill the target of their election campaigns in 1980 and 1982 but Democrats managed to retain their majorities in both years.

The roles of the parties reversed in 1994 when, after spending forty years in the minority, the Republicans regained control of the House with the "Contract with America", an idea spearheaded by Minority Whip Newt Gingrich. Speaker Gingrich would regularly clash with Democratic President Bill Clinton, leading to the United States federal government shutdown of 1995 and 1996, in which Clinton was largely seen to have prevailed. Gingrich's hold on the leadership was weakened significantly by that and several other controversies, and he faced a caucus revolt in 1997. After the Republicans lost House seats in 1998 (although retaining a majority) he did not stand for a third term as Speaker. His successor, Dennis Hastert, had been chosen as a compromise candidate, since the other Republicans in the leadership were more controversial. Hastert played a much less prominent role than other contemporary Speakers, being overshadowed by House Majority Leader Tom DeLay and President George W. Bush. The Republicans came out of the 2000 elections with a further reduced majority but made small gains in 2002 and 2004. The periods of 2001-2002 and 2003-2007 were the first times since 1953-1955 that there was single-party Republican leadership in Washington, interrupted from 2001-2003 as Senator Jim Jeffords of Vermont left the Republican Party to become independent and caucused with Senate Democrats to give them a 51-49 majority.

In the 2006 midterm elections, the Democrats won a majority in the House. Nancy Pelosi became Speaker when the 110th Congress convened on January 4, 2007, making her the first female to hold the office. With the election of Barack Obama as President and Democratic gains in both houses of Congress, Pelosi became the first Speaker since Tom Foley to hold the office during single-party Democratic leadership in Washington.[11] During the 111th Congress, Pelosi was the driving force behind several of Obama's major initiatives that proved controversial, and the Republicans campaigned against the Democrats' legislation by staging a "Fire Pelosi" bus tour[12] and regained control of the House in the 2010 midterm elections. House Minority Leader John Boehner was elected as Speaker.[13]

Notable elections

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the United States |

|

Executive

|

|

Politics portal |

Historically, there have been several controversial elections to the Speakership, such as the contest of 1839. In that case, even though the 26th United States Congress convened on December 2, the House could not begin the Speakership election until December 14 because of an election dispute in New Jersey known as the "Broad Seal War". Two rival delegations, one Whig and the other Democrat, had been certified as elected by different branches of the New Jersey government. The problem was compounded by the fact that the result of the dispute would determine whether the Whigs or the Democrats held the majority. Neither party agreed to permit a Speakership election with the opposite party's delegation participating. Finally, it was agreed to exclude both delegations from the election and a Speaker was finally chosen on December 17.

Another, more prolonged fight occurred in 1855 in the 34th United States Congress. The old Whig Party had collapsed but no single party had emerged to replace it. Candidates opposing the Democrats had run under a bewildering variety of labels, including Whig, Republican, American (Know Nothing), and simply "Opposition". By the time Congress actually met in December 1855, most of the northerners were concentrated together as Republicans, while most of the southerners and a few northerners used the American or Know Nothing label. Opponents of the Democrats held a majority in House, with the party makeup of the 234 Representatives being 83 Democrats, 108 Republicans, and 43 Know Nothings (primarily southern oppositionists). The Democratic minority nominated William Alexander Richardson of Illinois as Speaker, but because of sectional distrust, the various oppositionists were unable to agree on a single candidate for Speaker. The Republicans supported Nathaniel Prentiss Banks of Massachusetts, who had been elected as a Know Nothing but was now largely identified with the Republicans. The southern Know Nothings supported first Humphrey Marshall of Kentucky, and then Henry M. Fuller of Pennsylvania. The voting went on for almost two months with no candidate able to secure a majority, until it was finally agreed to elect the Speaker by plurality vote, and Banks was elected.[14] The House found itself in a similar dilemma when the 36th Congress met in December 1859. Although the Republicans held a plurality, the Republican candidate, John Sherman, was unacceptable to southern oppositionists due to his anti-slavery views, and once again the House was unable to elect a Speaker for several months. After Democrats allied with southern oppositionists to nearly elect the North Carolina oppositionist William N. H. Smith, Sherman finally withdrew in favor of compromise candidate William Pennington of New Jersey, a former Whig of unclear partisan loyalties, who was finally elected Speaker at the end of January 1860.[15]

The last Speakership elections in which the House had to vote more than once occurred in the 65th and 72nd United States Congress. In 1917, neither the Republican nor the Democratic candidate could attain a majority because three members of the Progressive Party and other individual members of other parties voted for their own party. The Republicans had a plurality in the House but James "Champ" Clark remained Speaker of the House because of the support of the Progressive Party members. In 1931, both the Republicans and the Democrats had 217 members with the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party having one member who served as the deciding vote. The Farmer-Labor Party eventually voted for the Democrats' candidate for Speaker, John Nance Garner, who later became Vice President under Franklin Roosevelt.

In 1997, several Republican congressional leaders tried to force Speaker Newt Gingrich to resign. However, Gingrich refused since that would have required a new election for Speaker, which could have led to Democrats along with dissenting Republicans voting for Democrat Dick Gephardt (then Minority Leader) as Speaker. After the 1998 midterm elections where the Republicans lost seats, Gingrich did not stand for re-election. The next two figures in the House Republican leadership hierarchy, Majority Leader Richard Armey and Majority Whip Tom DeLay, chose not to run for the office. The chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, Bob Livingston, declared his bid for the Speakership, which was unopposed, making him Speaker-designate. It was then revealed, by Livingston himself, who had been publicly critical of President Bill Clinton's perjury during his sexual harassment trial, that he had engaged in an extramarital affair. He opted to resign from the House, despite being urged to stay on by House Democratic leader Gephardt. Subsequently, chief deputy whip Dennis Hastert was selected as Speaker. The Republicans retained their majorities in the 2000, 2002, and 2004 elections.

The Democrats won a majority of seats in the 2006 midterm elections. On November 16, 2006, Nancy Pelosi, who was then Minority Leader, was selected as Speaker-designate by House Democrats.[17] When the 110th Congress convened on January 4, 2007, she was elected as the 60th Speaker by a vote of 233-202, becoming the first woman elected Speaker of the House. Pelosi remained Speaker through the 111th Congress. For the 112th Congress, Republican John Boehner was unanimously designated Speaker-designate by House Republicans and was elected the 61st Speaker of the House. As a show of dissent, nineteen Democratic representatives voted for Democrats other than Pelosi, who had been chosen as House Minority Leader and the Democrats' candidate for Speaker.

Partisan role

The Constitution does not spell out the political role of the Speaker. As the office has developed historically, however, it has taken on a clearly partisan cast, very different from the Speakership of most Westminster-style legislatures, such as the Speaker of the British House of Commons, which is meant to be scrupulously non-partisan. The Speaker in the United States, by tradition, is the head of the majority party in the House of Representatives, outranking the Majority Leader. However, despite having the right to vote, the Speaker usually does not participate in debate and rarely votes.

The Speaker is responsible for ensuring that the House passes legislation supported by the majority party. In pursuing this goal, the Speaker may use his or her power to determine when each bill reaches the floor. They also chair the majority party's steering committee in the House. While the Speaker is the functioning head of the House majority party, the same is not true of the President pro tempore of the Senate, whose office is primarily ceremonial and honorary.

When the Speaker and the President belong to the same party, the Speaker tends to play the role in a more ceremonial light, as seen when Dennis Hastert played a very low-key role during the presidency of fellow Republican George W. Bush. Nevertheless, there are times when the Speaker plays a much larger role if the President is a fellow member of their party, and thus, the Speaker is tasked with pushing through the agenda of the majority party, often at the expense of the minority opposition. This can be seen, most of all, in the Speakership of Democratic-Republican Henry Clay, who personally ensured the presidential victory of fellow Democratic-Republican John Quincy Adams. On the other side of the aisle, Democrat Sam Rayburn was a key player in the passing of New Deal legislation under the presidency of fellow Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Republican Joseph Gurney Cannon (under Theodore Roosevelt) was particularly infamous for his marginalization of the minority Democrats and centralizing of authority to the Speakership. In more recent times, Speaker Nancy Pelosi played a role in continuing the push for health care reform during the presidency of fellow Democrat Barack Obama.[18] The Republicans campaigned against Pelosi and the Democrats' legislation with their "Fire Pelosi" bus tour.[12][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

On the other hand, when the Speaker and the President belong to opposite parties, the public role and influence of the Speaker tend to increase. As the highest-ranking member of the opposition party (and in effect a de facto Leader of the Opposition), the Speaker is normally the chief public opponent of the President's agenda. In this scenario, the Speaker is known for undercutting the President's agenda by blocking measures by the minority party or rejecting bills by the Senate. One famous instance came in the form of Thomas Brackett Reed (under Grover Cleveland), a Speaker notorious for his successful attempt to force the Democrats to vote on measures where the Republicans had clear majorities, which ensured that Cleveland's Democrats were in no position to challenge the Republicans in the House. Joseph Cannon was particularly unique in that he led the conservative "Old Guard" wing of the Republican Party, while his President - Theodore Roosevelt - was of the more progressive clique, and more than just marginalizing the Democrats, Cannon used his power to punish the dissidents in his party and obstruct the progressive wing of the Republican Party.

More modern examples include Tip O'Neill, who was a vocal opponent of President Ronald Reagan's economic and defense policies; Newt Gingrich, who fought a bitter battle with President Bill Clinton for control of domestic policy; Nancy Pelosi, who argued with President George W. Bush over the Iraq War;[13] and current Speaker John Boehner, who clashes with President Barack Obama over budget issues and health care.[27]

Presiding officer

As presiding office of the House of Representatives, the Speaker holds a variety of powers over the House and is the highest-ranking legislative official in the US government.[28] The Speaker may delegate his powers to member of the House to act as Speaker pro tempore and preside over the House in the Speaker's absence, but it has always been a member of the same party.[29] During important debates, the Speaker pro tempore is ordinarily a senior member of the majority party who may be chosen for his or her skill in presiding. At other times, more junior members may be assigned to preside to give them experience with the rules and procedures of the House. The Speaker may also designate a Speaker pro tempore for special purposes, such as designating a Representative whose district is near Washington, DC to sign enrolled bills during long recesses.

On the floor of the House, the presiding officer is always addressed as "Mister Speaker" or "Madam Speaker," even if it is a Speaker pro tempore, and not the Speaker. When the House resolves itself into a Committee of the Whole, the Speaker designates a member to preside over the Committee as the Chairman, who is addressed as "Mister Chairman" or "Madam Chairwoman." To speak, members must seek the presiding officer's recognition. The presiding officer may call on members as they please, and may therefore control the flow of debate. The presiding officer also rules on all points of order but such rulings may be appealed to the whole House. The Speaker is responsible for maintaining decorum in the House and may order the Sergeant-at-Arms to enforce House rules.

The Speaker's powers and duties extend beyond presiding in the chamber. In particular, the Speaker has great influence over the committee process. The Speaker selects nine of the thirteen members of the powerful Committee on Rules, subject to the approval of the entire majority party. The leadership of the minority party chooses the remaining four members. Furthermore, the Speaker appoints all members of select committees and conference committees. Moreover, when a bill is introduced, the Speaker determines which committee will consider it. As a member of the House, the Speaker is entitled to participate in debate and to vote but, by custom, only does so in exceptional circumstances. Ordinarily, the Speaker votes only when his or her vote would be decisive or on matters of great importance, such as constitutional amendments or major legislation.[30]

Other functions

Because joint sessions and joint meetings of Congress are held in the House chamber, the Speaker presides over all such joint sessions and meetings. However, the Twelfth Amendment and 3 U.S.C. § 15 require that the President of the Senate preside over joint sessions of Congress assembled to count electoral votes and to certify the results of a presidential election.

The Speaker is also responsible for overseeing the officers of the House: the Clerk, the Sergeant-at-Arms, the Chief Administrative Officer, and the Chaplain. The Speaker can dismiss any of these officers. The Speaker appoints the House Historian and the General Counsel and, jointly with the Majority and Minority Leaders, appoints the House Inspector General.

The Speaker is second in the presidential line of succession, immediately after the Vice President, under the Presidential Succession Act of 1947. The Speaker is followed in the line of succession by the President pro tempore of the Senate and by the heads of federal executive departments. Some scholars argue that this provision of the succession statute is unconstitutional.[31]

To date, the implementation of the Presidential Succession Act has never been necessary and no Speaker has ever acted as President. Implementation of the law almost became necessary in 1973 after the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew. At the time, many believed that President Richard Nixon would resign because of the Watergate scandal, allowing Speaker Carl Albert to succeed to the Presidency. However, before he resigned, Nixon appointed Gerald Ford as Vice President in accordance with the Twenty-fifth Amendment. Nevertheless, the United States government takes the Speaker's place in the line of succession seriously enough that, for example, since shortly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Speakers used military jets to fly back and forth to their districts and for other travel until Speaker Boehner discontinued the practice in 2011. The Speaker of the House is one of the officers to whom declarations of presidential inability or ability to resume the Presidency must be addressed under the Twenty-fifth Amendment.

List of Speakers of the United States House of Representatives

It includes the congressional district and political affiliation of each speaker as well as the number of their Congress and time they spent in the position.

| # | Speaker | Party | District | Congress | Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  Frederick Muhlenberg Frederick Muhlenberg |

Pro-Administration | Pennsylvania-AL | 1st | April 1, 1789 — March 4, 1791 |

| 2 |  Jonathan Trumbull, Jr. Jonathan Trumbull, Jr. |

Pro-Administration | Connecticut-4 | 2nd | October 24, 1791 — March 4, 1793 |

| 3 |  Frederick Muhlenberg Frederick Muhlenberg |

Anti-Administration | Pennsylvania-AL | 3rd | December 2, 1793 — March 4, 1795 |

| 4 |  Jonathan Dayton Jonathan Dayton |

Federalist | New Jersey-AL | 4th | December 7, 1795 — March 4, 1797 |

| 5th | May 15, 1797 — March 4, 1799 | ||||

| 5 |  Theodore Sedgwick Theodore Sedgwick |

Federalist | Massachusetts-1 | 6th | December 2, 1799 — March 4, 1801 |

| 6 |  Nathaniel Macon Nathaniel Macon |

Democratic-Republican | North Carolina-5 | 7th | December 7, 1801 — March 4, 1803 |

| North Carolina-6 | 8th | October 17, 1803 — March 4, 1805 | |||

| 9th | December 2, 1805 — March 4, 1807 | ||||

| 7 |  Joseph Bradley Varnum Joseph Bradley Varnum |

Democratic-Republican | Massachusetts-4 | 10th | October 26, 1807 — March 4, 1809 |

| 11th | May 22, 1809 — March 4, 1811 | ||||

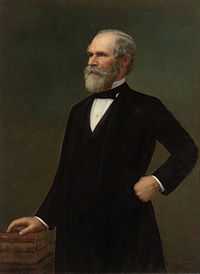

| 8 | |

Democratic-Republican | Kentucky-3 | 12th | November 4, 1811 — March 4, 1813 |

| Kentucky-2 | 13th | May 24, 1813 — January 19, 1814 | |||

| 9 |  Langdon Cheves Langdon Cheves |

Democratic-Republican | South Carolina-1 | January 19, 1814 — March 4, 1815 | |

| 10 | |

Democratic-Republican | Kentucky-2 | 14th | December 4, 1815 — March 4, 1817 |

| 15th | December 1, 1817 — March 4, 1819 | ||||

| 16th | December 6, 1819 — October 28, 1820 | ||||

| 11 |  John W. Taylor John W. Taylor |

Democratic-Republican | New York-11 | November 15, 1820 — March 4, 1821 | |

| 12 |  Philip Pendleton Barbour Philip Pendleton Barbour |

Democratic-Republican | Virginia-11 | 17th | December 4, 1821 — March 4, 1823 |

| 13 | |

Democratic-Republican | Kentucky-3 | 18th | December 1, 1823 — March 4, 1825 |

| 14 |  John W. Taylor John W. Taylor |

National Republican | New York-17 | 19th | December 5, 1825 — March 4, 1827 |

| 15 |  Andrew Stevenson Andrew Stevenson |

Democratic | Virginia-9 | 20th | December 3, 1827 — March 4, 1829 |

| 21st | December 7, 1829 — March 4, 1831 | ||||

| 22nd | December 5, 1831 — March 4, 1833 | ||||

| Virginia-11 | 23rd | December 2, 1833 — June 2, 1834 | |||

| 16 |  John Bell John Bell |

Whig | Tennessee-7 | June 2, 1834 — March 4, 1835 | |

| 17 |  James Polk James Polk |

Democratic | Tennessee-9 | 24th | December 7, 1835 — March 4, 1837 |

| 25th | September 4, 1837 — March 4, 1839 | ||||

| 18 |  Robert M. T. Hunter Robert M. T. Hunter |

Whig | Virginia-9 | 26th | December 16, 1839 — March 4, 1841 |

| 19 |  John White John White |

Whig | Kentucky-9 | 27th | May 31, 1841 — March 4, 1843 |

| 20 |  John Winston Jones John Winston Jones |

Democratic | Virginia-6 | 28th | December 4, 1843 — March 4, 1845 |

| 21 |  John Wesley Davis John Wesley Davis |

Democratic | Indiana-6 | 29th | December 1, 1845 — March 4, 1847 |

| 22 |  Robert Charles Winthrop Robert Charles Winthrop |

Whig | Massachusetts-1 | 30th | December 6, 1847 — March 4, 1849 |

| 23 |  Howell Cobb Howell Cobb |

Democratic | Georgia-6 | 31st | December 22, 1849 — March 4, 1851 |

| 24 |  Linn Boyd Linn Boyd |

Democratic | Kentucky-1 | 32nd | December 1, 1851 — March 4, 1853 |

| 33rd | December 5, 1853 — March 4, 1855 | ||||

| 25 |  Nathaniel P. Banks Nathaniel P. Banks |

Republican | Massachusetts-7 | 34th | February 2, 1856 — March 4, 1857 |

| 26 |  James Lawrence Orr James Lawrence Orr |

Democratic | South Carolina-5 | 35th | December 7, 1857 — March 4, 1859 |

| 27 |  William Pennington William Pennington |

Republican | New Jersey-5 | 36th | February 1, 1860 — March 4, 1861 |

| 28 |  Galusha A. Grow Galusha A. Grow |

Republican | Pennsylvania-14 | 37th | July 4, 1861 — March 4, 1863 |

| 29 |  Schuyler Colfax Schuyler Colfax |

Republican | Indiana-9 | 38th | December 7, 1863 — March 4, 1865 |

| 39th | December 4, 1865 — March 4, 1867 | ||||

| 40th | March 4, 1867 — March 3, 1869 | ||||

| 30 |  Theodore M. Pomeroy Theodore M. Pomeroy |

Republican | New York-24 | March 3, 1869 — March 4, 1869 | |

| 31 |  James G. Blaine James G. Blaine |

Republican | Maine-3 | 41st | March 4, 1869 — March 4, 1871 |

| 42nd | March 4, 1871 — March 4, 1873 | ||||

| 43rd | March 4, 1873 — March 4, 1875 | ||||

| 32 |  Michael C. Kerr Michael C. Kerr |

Democratic | Indiana-3 | 44th | December 6, 1875 — August 19, 1876 |

| 33 |  Samuel J. Randall Samuel J. Randall |

Democratic | Pennsylvania-3 | December 4, 1876 — March 4, 1877 | |

| 45th | October 15, 1877 — March 4, 1879 | ||||

| 46th | March 18, 1879 — March 4, 1881 | ||||

| 34 |  J. Warren Keifer J. Warren Keifer |

Republican | Ohio-8 | 47th | December 5, 1881 — March 4, 1883 |

| 35 |  John G. Carlisle John G. Carlisle |

Democratic | Kentucky-6 | 48th | December 3, 1883 — March 4, 1885 |

| 49th | December 7, 1885 — March 4, 1887 | ||||

| 50th | December 5, 1887 — March 4, 1889 | ||||

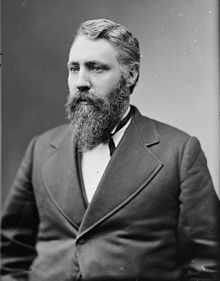

| 36 |  Thomas Brackett Reed Thomas Brackett Reed |

Republican | Maine-1 | 51st | December 2, 1889 — March 4, 1891 |

| 37 |  Charles Frederick Crisp Charles Frederick Crisp |

Democratic | Georgia-3 | 52nd | December 8, 1891 — March 4, 1893 |

| 53rd | August 7, 1893 — March 4, 1895 | ||||

| 38 |  Thomas Brackett Reed Thomas Brackett Reed |

Republican | Maine-1 | 54th | December 2, 1895 — March 4, 1897 |

| 55th | March 15, 1897 — March 4, 1899 | ||||

| 39 |  David B. Henderson David B. Henderson |

Republican | Iowa-3 | 56th | December 4, 1899 — March 4, 1901 |

| 57th | December 2, 1901 — March 4, 1903 | ||||

| 40 |  Joseph Gurney Cannon Joseph Gurney Cannon |

Republican | Illinois-18 | 58th | November 9, 1903 — March 4, 1905 |

| 59th | December 4, 1905 — March 4, 1907 | ||||

| 60th | December 2, 1907 — March 4, 1909 | ||||

| 61st | March 15, 1909 — March 4, 1911 | ||||

| 41 |  Champ Clark Champ Clark |

Democratic | Missouri-9 | 62nd | April 4, 1911 — March 4, 1913 |

| 63rd | April 7, 1913 — March 4, 1915 | ||||

| 64th | December 6, 1915 — March 4, 1917 | ||||

| 65th | April 2, 1917 — March 4, 1919 | ||||

| 42 |  Frederick Gillett Frederick Gillett |

Republican | Massachusetts-2 | 66th | May 19, 1919 — March 4, 1921 |

| 67th | April 11, 1921 — March 4, 1923 | ||||

| 68th | December 3, 1923 — March 4, 1925 | ||||

| 43 | |

Republican | Ohio-1 | 69th | December 7, 1925 — March 4, 1927 |

| 70th | December 5, 1927 — March 4, 1929 | ||||

| 71st | April 15, 1929 — March 4, 1931 | ||||

| 44 |  John Nance Garner John Nance Garner |

Democratic | Texas-15 | 72nd | December 7, 1931 — March 4, 1933 |

| 45 |  Henry Thomas Rainey Henry Thomas Rainey |

Democratic | Illinois-20 | 73rd | March 9, 1933 — August 19, 1934 |

| 46 |  Joseph Wellington Byrns Joseph Wellington Byrns |

Democratic | Tennessee-5 | 74th | January 3, 1935 — June 4, 1936 |

| 47 |  William B. Bankhead William B. Bankhead |

Democratic | Alabama-7 | June 4, 1936 — January 3, 1937 | |

| 75th | January 5, 1937 — January 3, 1939 | ||||

| 76th | January 3, 1939 — September 15, 1940 | ||||

| 48 |  Sam Rayburn Sam Rayburn |

Democratic | Texas-4 | September 16, 1940 — January 3, 1941 | |

| 77th | January 3, 1941 — January 3, 1943 | ||||

| 78th | January 6, 1943 — January 3, 1945 | ||||

| 79th | January 3, 1945 — January 3, 1947 | ||||

| 49 |  Joseph William Martin, Jr. Joseph William Martin, Jr. |

Republican | Massachusetts-14 | 80th | January 3, 1947 — January 3, 1949 |

| 50 |  Sam Rayburn Sam Rayburn |

Democratic | Texas-4 | 81st | January 3, 1949 — January 3, 1951 |

| 82nd | January 3, 1951 — January 3, 1953 | ||||

| 51 |  Joseph William Martin, Jr. Joseph William Martin, Jr. |

Republican | Massachusetts-14 | 83rd | January 3, 1953 — January 3, 1955 |

| 52 |  Sam Rayburn Sam Rayburn |

Democratic | Texas-4 | 84th | January 3, 1955 — January 3, 1957 |

| 85th | January 3, 1957 — January 3, 1959 | ||||

| 86th | January 7, 1959 — January 3, 1961 | ||||

| 87th | January 3, 1961 — November 16, 1961 | ||||

| 53 |  John William McCormack John William McCormack |

Democratic | Massachusetts-12 | January 10, 1962 — January 3, 1963 | |

| Massachusetts-9 | 88th | January 9, 1963 — January 3, 1965 | |||

| 89th | January 4, 1965 — January 3, 1967 | ||||

| 90th | January 10, 1967 — January 3, 1969 | ||||

| 91st | January 3, 1969 — January 3, 1971 | ||||

| 54 |  Carl Albert Carl Albert |

Democratic | Oklahoma-3 | 92nd | January 21, 1971 — January 3, 1973 |

| 93rd | January 3, 1973 — January 3, 1975 | ||||

| 94th | January 14, 1975 — January 3, 1977 | ||||

| 55 |  Tip O'Neill Tip O'Neill |

Democratic | Massachusetts-8 | 95th | January 4, 1977 — January 3, 1979 |

| 96th | January 15, 1979 — January 3, 1981 | ||||

| 97th | January 5, 1981 — January 3, 1983 | ||||

| 98th | January 3, 1983 — January 3, 1985 | ||||

| 99th | January 3, 1985 — January 3, 1987 | ||||

| 56 |  Jim Wright Jim Wright |

Democratic | Texas-12 | 100th | January 6, 1987 — January 3, 1989 |

| 101st | January 3, 1989 — June 6, 1989 | ||||

| 57 |  Tom Foley Tom Foley |

Democratic | Washington-5 | June 6, 1989 — January 3, 1991 | |

| 102nd | January 3, 1991 — January 3, 1993 | ||||

| 103rd | January 5, 1993 — January 3, 1995 | ||||

| 58 |  Newt Gingrich Newt Gingrich |

Republican | Georgia-6 | 104th | January 4, 1995 — January 3, 1997 |

| 105th | January 7, 1997 — January 3, 1999 | ||||

| 59 |  Dennis Hastert Dennis Hastert |

Republican | Illinois-14 | 106th | January 6, 1999 — January 3, 2001 |

| 107th | January 3, 2001 — January 3, 2003 | ||||

| 108th | January 7, 2003 — January 3, 2005 | ||||

| 109th | January 3, 2005 — January 3, 2007 | ||||

| 60 |  Nancy Pelosi Nancy Pelosi |

Democratic | California-12 | 110th | January 4, 2007 — January 3, 2009 |

| 111th | January 6, 2009 — January 3, 2011 | ||||

| 61 |  John Boehner John Boehner |

Republican | Ohio-8 | 112th | January 5, 2011 – January 3, 2013 |

| 113th | January 3, 2013 – January 3, 2015 | ||||

| 114th | January 6, 2015 – Present |

* Note: Banks, a former Democrat originally elected as a Know Nothing, had come to be associated with the Republicans by the time the 34th Congress convened. Because the Republicans did not command a majority in Congress, and Banks did not receive any votes from Democrats or southern Know Nothings, Banks, after two months of deadlocked balloting, could only be elected after a motion was passed allowing the election of a speaker by plurality vote.

List of Speakers by time in office

Sam Rayburn served for 17 years, 53 days |

Tip O'Neill served for 9 years, 350 days |

John W. McCormack served for 8 years, 344 days |

Theodore M. Pomeroy served for just 1 day |

This list is based on the difference between dates; if counted by number of calendar days all the figures would be one greater. Time after adjournment of one Congress but before the convening of the next Congress is not counted. For example, Nathaniel Macon was Speaker in both the 8th and 9th Congresses, but the eight-month gap between the two Congresses is not counted toward his service.

Sam Rayburn is the only person to have served as Speaker of the House for more than ten years.

Theodore M. Pomeroy served as Speaker of the House for one day after Speaker Schuyler Colfax resigned to become Vice President of the United States; Pomeroy's term as a Member of Congress ended the next day.

Sam Rayburn, Henry Clay, Thomas Brackett Reed, Joseph William Martin, Jr., Frederick Muhlenberg, and John W. Taylor are the only Speakers of the House to have ever served in non-consecutive Congresses (i.e. another Speaker served in between each tenure).

| Rank | Speaker | Order in office |

Time in office |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sam Rayburn | 48, 50, 52 | 17 years, 53 days |

| 2 | Tip O'Neill | 55 | 9 years, 350 days |

| 3 | John W. McCormack | 53 | 8 years, 344 days |

| 4 | Dennis Hastert | 59 | 7 years, 359 days |

| 5 | Champ Clark | 41 | 6 years, 357 days |

| 6 | Henry Clay | 08, 10, 13 | 6 years, 231 days |

| 7 | Carl Albert | 54 | 5 years, 337 days |

| 8 | Joseph Gurney Cannon | 40 | 5 years, 285 days |

| 9 | Tom Foley | 57 | 5 years, 209 days |

| 10 | James G. Blaine | 31 | 5 years, 93 days |

| 11 | Frederick H. Gillett | 42 | 4 years, 341 days |

| 12 | Schuyler Colfax | 29 | 4 years, 176 days |

| 13 | Thomas Brackett Reed | 36, 38 | 4 years, 172 days |

| 14 | Nicholas Longworth | 43 | 4 years, 133 days |

| 15 | John Boehner | 61 | 4 years, 116 days |

| 16 | William B. Bankhead | 47 | 4 years, 102 days |

| 17 | Andrew Stevenson | 15 | 4 years, 83 days |

| 18 | Joseph William Martin, Jr. | 49, 51 | 4 years |

| 19 | Nancy Pelosi | 60 | 3 years, 363 days |

| 20 | Newt Gingrich | 58 | 3 years, 361 days |

| 21 | Nathaniel Macon | 06 | 3 years, 317 days |

| 22 | John G. Carlisle | 35 | 3 years, 267 days |

| 23 | Samuel J. Randall | 33 | 3 years, 215 days |

| 24 | Frederick Muhlenberg | 01, 03 | 3 years, 64 days |

| 25 | Joseph Bradley Varnum | 07 | 3 years, 49 days |

| 26 | Jonathan Dayton | 04 | 3 years, 14 days |

| 27 | Charles Frederick Crisp | 37 | 2 years, 295 days |

| 28 | James K. Polk | 17 | 2 years, 268 days |

| 29 | Linn Boyd | 24 | 2 years, 182 days |

| 30 | David B. Henderson | 39 | 2 years, 182 days |

| 31 | Jim Wright | 56 | 2 years, 151 days |

| 32 | John White | 19 | 1 years, 277 days |

| 33 | Galusha A. Grow | 28 | 1 years, 243 days |

| 34 | John W. Taylor | 11, 14 | 1 year, 198 days |

| 35 | Henry Thomas Rainey | 45 | 1 years, 163 days |

| 36 | Joseph W. Byrns, Sr. | 46 | 1 years, 153 days |

| 37 | Jonathan Trumbull, Jr. | 02 | 1 years, 131 days |

| 38 | John Wesley Davis | 21 | 1 years, 93 days |

| 39 | Theodore Sedgwick | 05 | 1 years, 92 days |

| 40 | Philip Pendleton Barbour | 12 | 1 years, 90 days |

| 41 | John Winston Jones | 20 | 1 years, 90 days |

| 42 | J. Warren Keifer | 34 | 1 years, 89 days |

| 43 | Robert Charles Winthrop | 22 | 1 years, 88 days |

| 44 | James Lawrence Orr | 26 | 1 years, 87 days |

| 45 | John Nance Garner | 44 | 1 years, 87 days |

| 46 | Robert M. T. Hunter | 18 | 1 years, 78 days |

| 47 | Howell Cobb | 23 | 1 years, 72 days |

| 48 | Langdon Cheves | 09 | 1 years, 44 days |

| 49 | William Pennington | 27 | 1 years, 31 days |

| 50 | Nathaniel P. Banks | 25 | 1 years, 30 days |

| 51 | John Bell | 16 | 275 days |

| 52 | Michael C. Kerr | 32 | 257 days |

| 53 | Theodore M. Pomeroy | 30 | 1 day |

Number of Speakers per State

- Referring to individual

List of living former Speakers

Since the death of former Speaker Tom Foley on October 18, 2013, there are now four living former Speakers.

| Speaker | Years in office | |

|---|---|---|

| Jim Wright | 1987 – 1989 | December 22, 1922 |

| Newt Gingrich | 1995 – 1999 | June 17, 1943 |

| Dennis Hastert | 1999 – 2007 | January 2, 1942 |

| Nancy Pelosi | 2007 – 2011 | March 26, 1940 |

Recent election results

To be elected as Speaker, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all votes cast for individuals, excluding those who abstain.

Speaker of the United States House of Representatives election, 2007

Source: Election of the Speaker Office of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives. January 4, 2007.

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| √ Nancy Pelosi (D) | 233 | 53.6% | |

| John Boehner (R) | 202 | 46.4% | |

| Total | 435 | 100.0% | |

Speaker of the United States House of Representatives election, 2009

Source: Election of the Speaker Office of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives. January 6, 2009.

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| √ Nancy Pelosi (D) | 255 | 59.4% | |

| John Boehner (R) | 174 | 40.6% | |

| Total | 429 | 100.0% | |

| Not voting | 5 | 0.9% | |

| Vacant | 1 | ||

Speaker of the United States House of Representatives election, 2011

Source: Election of the Speaker Office of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives. January 5, 2011.

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| √ John Boehner (R) | 242 | 55.6% | |

| Nancy Pelosi (D) | 173 | 39.8% | |

| Heath Shuler (D) | 11 | 2.5% | |

| John Lewis (D) | 2 | <1.0% | |

| Dennis Cardoza (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Jim Costa (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Jim Cooper (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Steny Hoyer (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Marcy Kaptur (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Total | 433 | 100.0% | |

| "Present" | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Not voting | 1 | <1.0% | |

Speaker of the United States House of Representatives election, 2013

Source: Election of the Speaker Office of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives. January 3, 2013.

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| √ John Boehner (R) | 220 | 50.8% | |

| Nancy Pelosi (D) | 192 | 44.3% | |

| Eric Cantor (R) | 3 | <1.0% | |

| Jim Cooper (D) | 2 | <1.0% | |

| Allen West (R)[lower-alpha 1] | 2 | <1.0% | |

| Justin Amash (R) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| John Dingell (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Jim Jordan (R) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Raul Labrador (R) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| John Lewis (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Colin Powell (R)[lower-alpha 1] | 1 | <1.0% | |

| David Walker[lower-alpha 1] | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Total | 426 | 100.0% | |

| "Present" | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Not voting | 6 | 1.4% | |

| Vacant | 2 | ||

Speaker of the United States House of Representatives election, 2015

Source: Election of the Speaker Office of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives. January 6, 2015.

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| √ John Boehner (R) | 216 | 52.9% | |

| Nancy Pelosi (D) | 164 | 40.2% | |

| Dan Webster (R) | 12 | 2.9% | |

| Louie Gohmert (R) | 3 | <1.0% | |

| Ted Yoho (R) | 2 | <1.0% | |

| Jim Jordan (R) | 2 | <1.0% | |

| Jeff Duncan (R) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Rand Paul (R)[lower-alpha 1] | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Colin Powell (R)[lower-alpha 1] | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Trey Gowdy (R) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Kevin McCarthy (R) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Jim Cooper (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Peter DeFazio (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Jeff Sessions (R)[lower-alpha 1] | 1 | <1.0% | |

| John Lewis (D) | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Total | 408 | 100.0% | |

| "Present" | 1 | <1.0% | |

| Not voting | 25 | ||

| Vacant | 1 | ||

See also

- Leaders of the United States House of Representatives

Bibliography

- Beth, Richard S.; Heitshusen, Valerie (January 4, 2013). "Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- Garraty, John, ed. American National Biography (1999) 20 volumes; contains scholarly biographies of all Speakers no longer alive.

- Green, Matthew N. The Speaker of the House: A Study of Leadership (Yale University Press; 2010) 292 pages; Examines partisan pressures and other factors that shaped the leadership of the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives; focuses on the period since 1940.

- Remini, Robert V. The House: the history of the House of Representatives (Smithsonian Books, 2006), the standard scholarly history

- Rohde, David W. Parties and Leaders in the Postreform House (1991)

- Smock, Raymond W., and Susan W. Hammond, eds. Masters of the House: Congressional Leadership Over Two Centuries (1998) short biographies of key leaders

- Zelizer. Julian E. ed. The American Congress: The Building of Democracy (2004) comprehensive history by 40 scholars

Notes

References

- ↑ "Office of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives". Clerk.house.gov. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ↑ See the United States Presidential Line of Succession statute, 3 U.S.C. § 19

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL30857.pdf

- ↑ Ripley, Party Leaders in the House of Representatives, pp. 98-99.

- ↑ Oswald Seidensticker, "Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, Speaker of the House of Representatives, in the First Congress, 1789," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 13, No. 2 (Jul. 1889), pp. 184-206 in JSTOR

- ↑ C Stewart III, Architect or tactician? Henry Clay and the institutional development of the US House of Representatives" 1998, online

- ↑ Robinson, William A. "Thomas B. Reed, Parliamentarian". The American Historical Review, October 1931. pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Oleszek, Walter J. (December 1998). "A Pre-Twentieth Century Look at the House Committee on Rules". U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- ↑ Charles O. Jones, "Joseph G. Cannon and Howard W. Smith: An Essay on the Limits of Leadership in the House of Representatives," Journal of Politics (1968), 30: 617-646 doi:10.2307/2128798

- ↑ "Sam Rayburn House Museum". Texas Historical Commission. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- ↑ See Party Divisions of United States Congresses

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Condon, Stephanie (August 6, 2010). "GOP to Launch "Fire Pelosi" Bus Tour". CBS News. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sanchez, Ray (November 3, 2010). "Nancy Pelosi: House Speaker's Exclusive Interview With Diane Sawyer - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ↑ Allan Nevins. Ordeal of the Union, Volume II: A House Dividing 1852-1857 (New York, 1947), 413-415.

- ↑ Allan Nevins. The Emergence of Lincoln, Volume II: Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861 (New York, 1950), 116-123.

- ↑ Bush, George W. (January 23, 2007). "President Bush Delivers State of the Union Address". The White House. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- ↑ San Francisco Commission on the Status of Women. City & County of San Francisco, November 16, 2006. Retrieved on July 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Nancy Pelosi steeled White House for health push - Carrie Budoff Brown and Glenn Thrush". Politico.Com. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ↑ Braver, Rita (October 17, 2010). "Nancy Pelosi Fires Back". CBS News. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ Lester, Kerry (October 14, 2010). "'Fire Pelosi Bus Tour' not joint endeavor". Daily Herald. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ Gavin, Patrick (September 16, 2010). "The List: RNC's 'Fire Pelosi' Bus Tour". The Politico. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ "RNC's "Fire Pelosi" bus tour stops in Waco". CBS. September 26, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ Knickerbocker, Brad (September 15, 2010). "Michael Steele's 'Fire Pelosi' bus tour: 48 states or bust". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ Krotzer, Chelsea (October 10, 2010). "Republican leader urges party faithful to 'Fire Pelosi'". Billings Gazette. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ Hamby, Peter (September 24, 2010). "Steele's bus tour draws crowds, but also critics". CNN. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ Bowman, Quinn (September 15, 2010). "RNC Chairman Steele Urges Unity as He Rolls Out 'Fire Pelosi' Bus Tour". PBS. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ Hurst, Steven R. (January 5, 2011). "Republicans take charge of US House, poised for clashes with Obama over spending, health care". 1310 News. Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- ↑ Speaker of the House Law & Legal Definition. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Speaker Pro Tempore Law & Legal Definition. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ [Americapedia: Taking the Dumb Out of Freedom Jodi Lynn Anderson, Daniel Ehrenhaft & Andisheh Nouraee] 2011, Bloomsbury Publishing Page 26.

- ↑ See Akhil Reed Amar & Vikram Amar,Is The Presidential Succession Law Constitutional?, 48 Stan. L. Rev. 113 (1995). This issue is discussed in the entry on the United States Presidential Line of Succession

External links

- "Capitol Questions." C-SPAN (2003). Notable elections and role.

- The Cannon Centenary Conference: The Changing Nature of the Speakership. (2003). House Document 108-204. History, nature and role of the Speakership.

- Congressional Quarterly's Guide to Congress, 5th ed. (2000). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Press.

- Speaker of the House of Representatives. (2005). Official Website. Information about role as party leader, powers as presiding officer.

- Wilson, Woodrow. (1885). Congressional Government. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

| United States presidential line of succession | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Vice President Joe Biden |

2nd in line | Succeeded by President pro tempore of the Senate Orrin Hatch |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||