Spanish cruiser Isla de Cuba

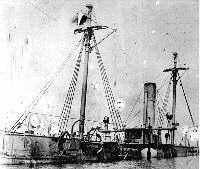

Isla de Cuba soon after completion, probably in a British port | |

| Career | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Isla de Cuba |

| Namesake: | The island of Cuba in the Caribbean |

| Builder: | Elswick, United Kingdom |

| Cost: | 2,400,000 pesetas |

| Laid down: | 25 February 1886 |

| Launched: | 11 December 1886 |

| Completed: | 22 September 1887 |

| Commissioned: | 1887 |

| Fate: | Scuttled 1 May 1898; captured and salvaged by the United States Navy |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Isla de Luzon-class |

| Type: | protected cruiser |

| Displacement: | 1,030 tons |

| Length: | 184 ft 10 in (56.34 m) |

| Beam: | 29 ft 11 in (9.12 m) |

| Draft: | 12 ft 6 in (3.81 m) maximum |

| Installed power: | 1,897 ihp (natural draft) 2,627 ihp (forced draft) |

| Propulsion: | 2-shaft horizontal triple-expansion, 2 cylindrical boilers |

| Speed: | 14.2 knots (natural draft) 15.9 knots (forced draft) |

| Complement: | 164 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: | 6 × 4.7 in (120 mm) guns 8 × 6 pdr quick-firing guns 4 × machine guns 3 × 14 in (356 mm) torpedo tubes |

| Armor: | Deck 2.5 in (64 mm)-1 in (25 mm); conning tower 2 in (51 mm) |

| Notes: | Coal 164 tons (normal); 200 tons (maximum) |

Isla de Cuba was an Isla de Luzon class second-class protected cruiser of the Spanish Navy which fought in the Battle of Manila Bay.

Technical Characteristics

In January 1886, Spain placed orders for two small protected cruisers, the Isla de Luzon'' and the Isla de Cuba with the British shipbuilding company Armstrongs to be built at their Elswick, Tyne and Wear shipyard.[1]

The ship was built with a main armament of six 120 mm (4.7 in) guns, with a secondary battery of four six pounder (57 mm guns), and three 14 in torpedo tubes. The ship's protective armour deck had a thickness of between 2 1⁄2–1 in (64–25 mm), while the ship's conning tower had 2 in (51 mm) of armour.[1]

She was laid down on 25 February 1886, launched on 11 December 1886, and completed on 22 September 1887.[2] She had a steel hull and one funnel.[3] Having a wide beam for her length, she had poor seakeeping qualities and tended to bury her bow in waves.[2] Small for a protected cruiser, she was often called a gunboat by 1898.

Operational history

Upon completion, Isla de Cuba joined the Metropolitan Fleet in Spain. She participated in the Rif War of 1893–1894, bombarding the reef between Melilla ad Chafarinos. When the Philippine Revolution of 1896–1898 broke out in the Philippines, Isla de Cuba was sent there to join the squadron of Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo de Pasaron.[2]

She was still part of Montojo's squadron when the Spanish-American War began in April 1898. She was anchored with the squadron in Cañacao Bay under the lee of the Cavite Peninsula east of Sangley Point, Luzon, eight miles southwest of Manila, when, early on the morning of 1 May 1898, the United States Navy's Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey, found Montojo's anchorage and attacked. The resulting Battle of Manila Bay was the first major engagement of the Spanish-American War.[4]

The American squadron made a series of firing passes, wreaking great havoc on the Spanish ships.[4] At first, Dewey's ships concentrated their fire on Montojo's flagship, unprotected cruiser Reina Cristina, and on unprotected cruiser Castilla, and Isla de Cuba suffered little damage. When Reina Cristina was disabled, Isla de Cuba and her sister ship, Isla de Luzon, came alongside the sinking Reina Cristina to assist her under heavy American gunfire. Admiral Montojo shifted his flag to Isla de Cuba.[2]

When Montojo's squadron had been battered into submission, Isla de Cuba was scuttled in shallow water to avoid capture. Her upper works remained above the water, and a team from gunboat USS Petrel went aboard and set Isla de Cuba on fire.[2]

After the United States occupied the Philippines, the United States Navy seized, salvaged, and repaired Isla de Cuba and commissioned her as gunboat USS Isla de Cuba in 1900 for service in the Philippines.[2]

See also

- USS Isla de Cuba

- Navsource.org: USS Isla de Cuba

Notes

References

- Alden, John D. The American Steel Navy: A Photographic History of the U.S. Navy from the Introduction of the Steel Hull in 1883 to the Cruise of the Great White Fleet, 1907–1909. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1972. ISBN 0-87021-248-6.

- Brook, Peter. Warships for Export: Armstrongs Warships 1867–1927. Gravesend, UK: World Ship Society, 1999. ISBN 0-905617-89-4.

- Chesneau, Roger, and Eugene M. Kolesnik, Eds. Conway's All The World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. New York, New York: Mayflower Books Inc., 1979. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Nofi, Albert A. The Spanish-American War. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Combined Books Inc., 1996. ISBN 0-938289-57-8.

- Department of the Navy: Naval Historical Center: Online Library of Selected Images: Spanish Navy Ships: 'Isla de Cuba (Cruiser, 1886–1898)

| ||||||||||