Spain

| Kingdom of Spain |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Plus Ultra" (Latin) "Further Beyond" |

||||||

| Anthem: "Marcha Real" |

||||||

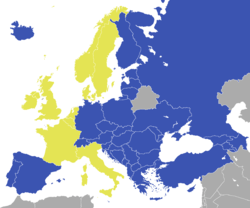

![Location of Spain (dark green)– in Europe (green & dark grey)– in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](../I/m/EU-Spain.svg.png) Location of Spain (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

||||||

-UNOCHA-no-logo.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Madrid 40°26′N 3°42′W / 40.433°N 3.700°W | |||||

| Official language and national language |

Spanish[lower-alpha 3] | |||||

| Recognised regional languages[lower-alpha 3] |

||||||

| Ethnic groups (2011) |

|

|||||

| Demonym | ||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | |||||

| - | Monarch | Felipe VI | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Mariano Rajoy | ||||

| Legislature | General Courts | |||||

| - | Upper house | Senate | ||||

| - | Lower house | Congress of Deputies | ||||

| Formation | ||||||

| - | Dynastic | 1479 | ||||

| - | De facto | 1516 | ||||

| - | De jure | 1715 | ||||

| - | First constitution | 1812 | ||||

| - | Current democracy | 1978 | ||||

| - | EEC accession[lower-alpha 4] | 1986 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 505,990[2] km2 (52nd) 195,364 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 1.04 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2014 estimate | 46,464,053[3] (30th) | ||||

| - | 2011 census | 46,815,916[4] | ||||

| - | Density | 92/km2 (106th) 240/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $1.534 trillion[5] (16th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $32,975[5] (33rd) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2014 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $1.400 trillion[5] (14th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $30,113[5] (28th) | ||||

| Gini (2013) | 33.7[6] medium · high |

|||||

| HDI (2013) | very high · 27th |

|||||

| Currency | Euro[lower-alpha 5] (€) (EUR) | |||||

| Time zone | CET[lower-alpha 6] (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST[lower-alpha 6] (UTC+2) | ||||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +34 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | ES | |||||

| Internet TLD | .es[lower-alpha 7] | |||||

Spain (![]() i/ˈspeɪn/; Spanish: España [esˈpaɲa]), officially the Kingdom of Spain (Spanish: Reino de España),[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] is a sovereign state located on the Iberian Peninsula in southwestern Europe. Its mainland is bordered to the south and east by the Mediterranean Sea except for a small land boundary with Gibraltar; to the north and northeast by France, Andorra, and the Bay of Biscay; and to the west and northwest by Portugal and the Atlantic Ocean. Along with France and Morocco, it is one of only three countries to have both Atlantic and Mediterranean coastlines. Spain's 1,214 km (754 mi) border with Portugal is the longest uninterrupted border within the European Union.

i/ˈspeɪn/; Spanish: España [esˈpaɲa]), officially the Kingdom of Spain (Spanish: Reino de España),[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] is a sovereign state located on the Iberian Peninsula in southwestern Europe. Its mainland is bordered to the south and east by the Mediterranean Sea except for a small land boundary with Gibraltar; to the north and northeast by France, Andorra, and the Bay of Biscay; and to the west and northwest by Portugal and the Atlantic Ocean. Along with France and Morocco, it is one of only three countries to have both Atlantic and Mediterranean coastlines. Spain's 1,214 km (754 mi) border with Portugal is the longest uninterrupted border within the European Union.

Spanish territory also includes two archipelagos; the Balearic Islands, in the Mediterranean Sea, and the Canary Islands, in the Atlantic Ocean off the African coast; two major exclaves, Ceuta and Melilla, in continental North Africa; and the islands and peñones (rocks) of Alborán, Alhucemas, Chafarinas and Vélez de la Gomera. With an area of 505,990 km2 (195,360 sq mi), Spain is the second largest country in Western Europe and the European Union, and the fourth largest country in Europe. By population, Spain is the sixth largest in Europe and the fifth in the European Union.

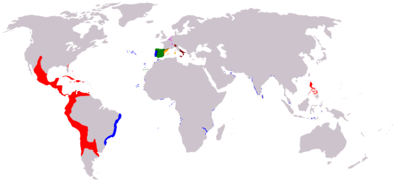

Modern humans first arrived in the Iberian Peninsula around 35,000 years ago. Iberian cultures along with ancient Phoenician, Greek and Carthaginian settlements developed on the peninsula until it came under Roman rule around 200 BCE, after which the region was named Hispania. In the Middle Ages, the area was conquered by Germanic tribes and later by the Moors. Spain emerged as a unified country in the 15th century, following the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs and the completion of the centuries-long reconquest, or Reconquista, of the peninsula from the Moors in 1492. In the early modern period, Spain became one of history's first global colonial empires, leaving a vast cultural and linguistic legacy that includes over 500 million Spanish speakers, making Spanish the world's second most spoken first language.

Spain is a democracy organised in the form of a parliamentary government under a constitutional monarchy. It is a developed country with the world's fourteenth largest economy by nominal GDP and sixteenth largest by purchasing power parity. It is a member of the United Nations (UN), the European Union (EU), the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Trade Organization (WTO) and many other international organisations.

Etymology

The origins of the Roman name Hispania, from which the modern name España was derived, are uncertain and are possibly unknown due to inadequate evidence. Down the centuries there have been a number of accounts and hypotheses:

The Renaissance scholar Antonio de Nebrija proposed that the word Hispania evolved from the Iberian word Hispalis, meaning "city of the western world".

Jesús Luis Cunchillos argues that the root of the term span is the Phoenecian word spy, meaning "to forge metals". Therefore i-spn-ya would mean "the land where metals are forged".[9] It may be a derivation of the Phoenician I-Shpania, meaning "island of rabbits", "land of rabbits" or "edge", a reference to Spain's location at the end of the Mediterranean; Roman coins struck in the region from the reign of Hadrian show a female figure with a coney at her feet,[10] and Strabo called it the "land of the rabbits".[11]

Hispania may derive from the poetic use of the term Hesperia, reflecting the Greek perception of Italy as a "western land" or "land of the setting sun" (Hesperia, Ἑσπερία in Greek) and Spain, being still further west, as Hesperia ultima.[12]

There is the claim that "Hispania" derives from the Basque word Ezpanna meaning "edge" or "border", another reference to the fact that the Iberian Peninsula constitutes the southwest corner of the European continent.[12]

Two 15th-century Spanish Jewish scholars, Don Isaac Abrabanel and Solomon ibn Verga, gave an explanation now considered folkloric. Both men wrote in two different published works that the first Jews to reach Spain were brought by ship by Phiros who was confederate with the king of Babylon when he laid siege to Jerusalem. This man was a Grecian by birth, but who had been given a kingdom in Spain. He became related by marriage to Espan, the nephew of king Heracles, who also ruled over a kingdom in Spain. Heracles later renounced his throne in preference for his native Greece, leaving his kingdom to his nephew, Espan, from whom the country of España (Spain) took its name. Based upon their testimonies, this eponym would have already been in use in Spain by c. 350 BCE.[13]

History

Iberia enters written records as a land populated largely by the Iberians, Basques and Celts. After an arduous conquest, the peninsula came under the rule of the Roman Empire. During the early Middle Ages it came under Germanic rule but later, much of it was conquered by Moorish invaders from North Africa. In a process that took centuries, the small Christian kingdoms in the north gradually regained control of the peninsula. The last Moorish kingdom fell in the same year Columbus reached the Americas. A global empire began which saw Spain become the strongest kingdom in Europe, the leading world power for a century and a half, and the largest overseas empire for three centuries.

Continued wars and other problems eventually led to a diminished status. The Napoleonic invasions of Spain led to chaos, triggering independence movements that tore apart most of the empire and left the country politically unstable. Prior to the Second World War, Spain suffered a devastating civil war and came under the rule of an authoritarian government, which oversaw a period of stagnation that was followed by a surge in the growth of the economy. Eventually democracy was peacefully restored in the form of a parliamentary constitutional monarchy. Spain joined the European Union, experiencing a cultural renaissance and steady economic growth.

Prehistory and pre-Roman peoples

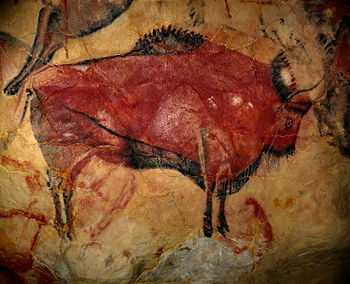

Archaeological research at Atapuerca indicates the Iberian Peninsula was populated by hominids 1.2 million years ago.[15] In Atapuerca fossils have been found of the earliest known hominins in Europe, the Homo antecessor. Modern humans first arrived in Iberia, from the north on foot, about 35,000 years ago.[16] The best known artefacts of these prehistoric human settlements are the famous paintings in the Altamira cave of Cantabria in northern Iberia, which were created from 35,600 to 13,500 BCE by Cro-Magnon.[14][17] Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that the Iberian Peninsula acted as one of several major refugia from which northern Europe was repopulated following the end of the last ice age.

The largest groups inhabiting the Iberian Peninsula before the Roman conquest were the Iberians and the Celts. The Iberians inhabited the Mediterranean side of the peninsula, from the northeast to the southeast. The Celts inhabited much of the inner and Atlantic sides of the peninsula, from the northwest to the southwest. Basques occupied the western area of the Pyrenees mountain range and adjacent areas, the Tartessians were in the southwest and the Lusitanians and Vettones occupied areas in the central west. A number of trading settlements of Phoenicians, Greeks and Carthaginians developed on the Mediterranean coast.

Roman Empire and the Gothic Kingdom

During the Second Punic War, an expanding Roman Republic captured Carthaginian trading colonies along the Mediterranean coast from roughly 210 to 205 BCE. It took the Romans nearly two centuries to complete the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, though they had control of it for over six centuries. Roman rule was bound together by law, language, and the Roman road.[18]

The cultures of the Celtic and Iberian populations were gradually Romanised (Latinised) at differing rates in different parts of Hispania. Local leaders were admitted into the Roman aristocratic class[lower-alpha 8][19] Hispania served as a granary for the Roman market, and its harbours exported gold, wool, olive oil, and wine. Agricultural production increased with the introduction of irrigation projects, some of which remain in use. Emperors Hadrian, Trajan, Theodosius I, and the philosopher Seneca were born in Hispania.[lower-alpha 9] Christianity was introduced into Hispania in the 1st century CE and it became popular in the cities in the 2nd century CE.[19] Most of Spain's present languages and religion, and the basis of its laws, originate from this period.[18]

The weakening of the Western Roman Empire's jurisdiction in Hispania began in 409, when the Germanic Suebi and Vandals, together with the Sarmatian Alans crossed the Rhine and ravaged Gaul until the Visigoths drove them into Iberia that same year. The Suebi established a kingdom in what is today modern Galicia and northern Portugal. As the western empire disintegrated, the social and economic base became greatly simplified: but even in modified form, the successor regimes maintained many of the institutions and laws of the late empire, including Christianity.

The Alans' allies, the Hasdingi Vandals, established a kingdom in Gallaecia, too, occupying largely the same region but extending farther south to the Douro river. The Silingi Vandals occupied the region that still bears a form of their name—Vandalusia, modern Andalusia, in Spain. The Byzantines established an enclave, Spania, in the south, with the intention of reviving the Roman empire throughout Iberia. Eventually, however, Hispania was reunited under Visigothic rule.

Isidore of Seville, archbishop of Seville, was an influential philosopher and very studied in the Middle Ages in Europe. Also his theories were vital to the conversion of the Visigothic Kingdom to a Catholic one, in the Councils of Toledo. This Gothic kingdom was the first Christian kingdom ruling in the Iberian Peninsula, and in the Reconquista it was the referent for the different kingdoms fighting against the Muslim rule.

Middle Ages

In the 8th century, nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula was conquered (711–718) by largely Moorish Muslim armies from North Africa. These conquests were part of the expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate. Only a small area in the mountainous north-west of the peninsula managed to resist the initial invasion.

Under Islamic law, Christians and Jews were given the subordinate status of dhimmi. This status permitted Christians and Jews to practice their religions as People of the Book but they were required to pay a special tax and had legal and social rights inferior to those of Muslims.[20][21]

Conversion to Islam proceeded at an increasing pace. The muladíes (Muslims of ethnic Iberian origin) are believed to have comprised the majority of the population of Al-Andalus by the end of the 10th century.[22][23]

The Muslim community in the Iberian Peninsula was itself diverse and beset by social tensions. The Berber people of North Africa, who had provided the bulk of the invading armies, clashed with the Arab leadership from the Middle East.[lower-alpha 10] Over time, large Moorish populations became established, especially in the Guadalquivir River valley, the coastal plain of Valencia, the Ebro River valley and (towards the end of this period) in the mountainous region of Granada.[23]

Córdoba, the capital of the caliphate since Abd-ar-Rahman III, was the largest, richest and most sophisticated city in western Europe. Mediterranean trade and cultural exchange flourished. Muslims imported a rich intellectual tradition from the Middle East and North Africa. Muslim and Jewish scholars played an important part in reviving and expanding classical Greek learning in Western Europe. Some important philosophers at the time were Averroes, Ibn Arabi and Maimonides. The Romanised cultures of the Iberian Peninsula interacted with Muslim and Jewish cultures in complex ways, giving the region a distinctive culture.[23] Outside the cities, where the vast majority lived, the land ownership system from Roman times remained largely intact as Muslim leaders rarely dispossessed landowners and the introduction of new crops and techniques led to an expansion of agriculture.

In the 11th century, the Muslim holdings fractured into rival Taifa kingdoms, allowing the small Christian states the opportunity to greatly enlarge their territories.[23] The arrival from North Africa of the Islamic ruling sects of the Almoravids and the Almohads restored unity upon the Muslim holdings, with a stricter, less tolerant application of Islam, and saw a revival in Muslim fortunes. This re-united Islamic state experienced more than a century of successes that partially reversed Christian gains.

The Reconquista (Reconquest) was the centuries-long period in which Christian rule was re-established over the Iberian Peninsula. The Reconquista is viewed as beginning with the Battle of Covadonga won by Don Pelayo in 722 and was concurrent with the period of Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula. The Christian army's victory over Muslim forces led to the creation of the Christian Kingdom of Asturias along the northwestern coastal mountains. Shortly after, in 739, Muslim forces were driven from Galicia, which was to eventually host one of medieval Europe's holiest sites, Santiago de Compostela and was incorporated into the new Christian kingdom. The Kingdom of León was the strongest Christian kingdom for centuries. In 1188 the first modern parliamentary season in Europe were hold in León (Cortes of León). The Kingdom of Castile, formed from Leonese territory, was its successor as strongest kingdom. The kings and the nobility fought for power and influence in this period. The example of the roman emperors influenced the political objective of the Crown, while the nobles benefited from feudalism.

Muslim armies had also moved north of the Pyrenees but they were defeated by Frankish forces at the Battle of Poitiers, Frankia. Later, Frankish forces established Christian counties on the southern side of the Pyrenees. These areas were to grow into the kingdoms of Navarre, Aragon and Catalonia.[24] For several centuries, the fluctuating frontier between the Muslim and Christian controlled areas of Iberia was along the Ebro and Douro valleys.

The break-up of Al-Andalus into the competing taifa kingdoms helped the long embattled Iberian Christian kingdoms gain the initiative. The capture of the strategically central city of Toledo in 1085 marked a significant shift in the balance of power in favour of the Christian kingdoms. Following a great Muslim resurgence in the 12th century, the great Moorish strongholds in the south fell to Christian Spain in the 13th century—Córdoba in 1236 and Seville in 1248—leaving only the Muslim enclave of Granada as a tributary state in the south.[25]

In this period literature and philosophy started to flourish again in the Christian peninsular kingdoms, based on Roman and Gothic traditions. An important philosopher from this time is Ramon Llull. Abraham Cresques was a prominent Jewish cartographer. Roman law and its institutions were the model for the legislators. The king Alfonso X of Castile focused on strengthening this Roman and Gothic past, and also on linking the Iberian Christian kingdoms with the rest of medieval European Christendom. He worked for being elected emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and published the Siete Partidas code. The Toledo School of Translators is the name that commonly describes the group of scholars who worked together in the city of Toledo during the 12th and 13th centuries, to translate many of the philosophical and scientific works from Classical Arabic, Ancient Greek, and Ancient Hebrew. The Islamic transmission of the classics is the main Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe. The Castilian language—more commonly known (especially later in history and at present) as "Spanish" after becoming the national language and lingua franca of Spain—evolved from Vulgar Latin, as did other Romance languages of Spain like the Catalan, Asturian and Galician languages, as well as other Romance languages in Latin Europe. Basque, the only non-Romance language in Spain, continued evolving from Early Basque to Medieval. The Glosas Emilianenses founded in the monasteries of San Millán de la Cogolla contain the first written words in both Basque and Spanish, having the first one an influence in the formation of the second as an evolution of Latin.[26]

In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Marinid Muslim sect based in North Africa invaded and established some enclaves on the southern coast but failed in their attempt to re-establish Muslim rule in Iberia and were soon driven out. The 13th century also witnessed the Crown of Aragon, centred in Spain's north east, expand its reach across islands in the Mediterranean, to Sicily and even Athens.[27] Around this time the universities of Palencia (1212/1263) and Salamanca (1218/1254) were established. The Black Death of 1348 and 1349 devastated Spain.[28] In 1469, the crowns of the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were united by the marriage of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. 1478 commenced the completion of the conquest of the Canary Islands and in 1492, the combined forces of Castile and Aragon captured the Emirate of Granada, ending the last remnant of a 781-year presence of Islamic rule in Iberia. That same year, Spain's Jews were ordered to convert to Catholicism or face expulsion from Spanish territories during the Spanish Inquisition.[29] The Treaty of Granada guaranteed religious tolerance toward Muslims,[30] and although the toleration was only partial, it was not until the beginning of the 17th century, following the Revolt of the Alpujarras, that Muslims were finally expelled.[lower-alpha 11][31]

Imperial Spain

The year 1492 also marked the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World, during a voyage funded by Isabella. Columbus's first voyage crossed the Atlantic and reached the Caribbean Islands, beginning the European exploration and conquest of the Americas, although he remained convinced that he had reached the Orient. The colonisation of the Americas started, with conquistadores like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro. Miscegenation was the rule between the native and the European cultures and people.

As Renaissance New Monarchs, Isabella and Ferdinand centralised royal power at the expense of local nobility, and the word España, whose root is the ancient name Hispania, began to be commonly used to designate the whole of the two kingdoms.[31] With their wide-ranging political, legal, religious and military reforms, Spain emerged as the first world power.

The unification of the crowns of Aragon and Castile by the marriage of their sovereigns laid the basis for modern Spain and the Spanish Empire, although each kingdom of Spain remained a separate country, in social, political, laws, currency and language.[32][33]

Spain was Europe's leading power throughout the 16th century and most of the 17th century, a position reinforced by trade and wealth from colonial possessions and became the world's leading maritime power. It reached its apogee during the reigns of the first two Spanish Habsburgs—Charles I (1516–1556) and Philip II (1556–1598). This period saw the Italian Wars, the Revolt of the Comuneros, the Dutch Revolt, the Morisco Revolt, clashes with the Ottomans, the Anglo-Spanish War and wars with France.[34]

Through exploration and conquest or royal marriage alliances and inheritance, the Spanish Empire expanded to include vast areas in the Americas, islands in the Asia-Pacific area, areas of Italy, cities in Northern Africa, as well as parts of what are now France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. The first circumnavigation of the world was carried out in 1519-1521. It was the first empire on which it was said that the sun never set. This was an Age of Discovery, with daring explorations by sea and by land, the opening-up of new trade routes across oceans, conquests and the beginnings of European colonialism. Spanish explorers brought back precious metals, spices, luxuries, and previously unknown plants, and played a leading part in transforming the European understanding of the globe.[35] The cultural efflorescence witnessed during this period is now referred to as the Spanish Golden Age. The expansion of the empire caused immense upheaval in the Americas as the collapse of societies and empires and new diseases from Europe devastated American populations. The rise of humanism, the Counter-Reformation and new geographical discoveries and conquests raised issues that were addressed by the intellectual movement now known as the School of Salamanca, which developed the first modern theories of what are now known as international law and human rights.

In the late 16th century and first half of the 17th century, Spain was confronted by unrelenting challenges from all sides. Barbary pirates, under the aegis of the rapidly growing Ottoman Empire, disrupted life in many coastal areas through their slave raids and renewed the threat of an Islamic invasion.[36] This was at a time when Spain was often at war with France.

The Protestant Reformation dragged the kingdom ever more deeply into the mire of religiously charged wars. The result was a country forced into ever expanding military efforts across Europe and in the Mediterranean.[37]

By the middle decades of a war- and plague-ridden 17th-century Europe, the Spanish Habsburgs had enmeshed the country in continent-wide religious-political conflicts. These conflicts drained it of resources and undermined the economy generally. Spain managed to hold on to most of the scattered Habsburg empire, and help the imperial forces of the Holy Roman Empire reverse a large part of the advances made by Protestant forces, but it was finally forced to recognise the separation of Portugal (with whom it had been united in a personal union of the crowns from 1580 to 1640) and the Netherlands, and eventually suffered some serious military reverses to France in the latter stages of the immensely destructive, Europe-wide Thirty Years' War.[38]

.jpg)

In the latter half of the 17th century, Spain went into a gradual decline, during which it surrendered several small territories to France and the Netherlands; however, it maintained and enlarged its vast overseas empire, which remained intact until the beginning of the 19th century.

The decline culminated in a controversy over succession to the throne which consumed the first years of the 18th century. The War of the Spanish Succession was a wide-ranging international conflict combined with a civil war, and was to cost the kingdom its European possessions and its position as one of the leading powers on the Continent.[39] During this war, a new dynasty originating in France, the Bourbons, was installed. Long united only by the Crown, a true Spanish state was established when the first Bourbon king, Philip V, united the crowns of Castile and Aragon into a single state, abolishing many of the old regional privileges and laws.[40]

The 18th century saw a gradual recovery and an increase in prosperity through much of the empire. The new Bourbon monarchy drew on the French system of modernising the administration and the economy. Enlightenment ideas began to gain ground among some of the kingdom's elite and monarchy. Military assistance for the rebellious British colonies in the American War of Independence improved the kingdom's international standing.[41]

Liberalism and nation state

In 1793, Spain went to war against the revolutionary new French Republic as a member of the first Coalition. The subsequent War of the Pyrenees polarised the country in a reaction against the gallicised elites and following defeat in the field, peace was made with France in 1795 at the Peace of Basel in which Spain lost control over two-thirds of the island of Hispaniola. The Prime Minister, Manuel Godoy, then ensured that Spain allied herself with France and in the brief War of the Third Coalition which ended with the British victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. In 1807, a secret treaty between Napoleon and the unpopular prime minister led to a new declaration of war against Britain and Portugal. Napoleon's troops entered the country to invade Portugal but instead occupied Spain's major fortresses. The ridiculed Spanish king abdicated in favour of Napoleon's brother, Joseph Bonaparte.

Joseph Bonaparte was seen as a puppet monarch and was regarded with scorn by the Spanish. The 2 May 1808 revolt was one of many nationalist uprisings across the country against the Bonapartist regime.[42] These revolts marked the beginning of a devastating war of independence against the Napoleonic regime.[43] Napoleon was forced to intervene personally, defeating several Spanish armies and forcing a British army to retreat. However, further military action by Spanish armies, guerrillas and Wellington's British-Portuguese forces, combined with Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia, led to the ousting of the French imperial armies from Spain in 1814, and the return of King Ferdinand VII.[44]

During the war, in 1810, a revolutionary body, the Cortes of Cádiz, was assembled to co-ordinate the effort against the Bonapartist regime and to prepare a constitution.[45] It met as one body, and its members represented the entire Spanish empire.[46] In 1812 a constitution for universal representation under a constitutional monarchy was declared but after the fall of the Bonapartist regime Ferdinand VII dismissed the Cortes Generales and was determined to rule as an absolute monarch. These events foreshadowed the conflict between conservatives and liberals in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Spain's conquest by France benefited Latin American anti-colonialists who resented the Imperial Spanish government's policies that favored Spanish-born citizens (Peninsulars) over those born overseas (Criollos) and demanded retroversion of the sovereignty to the people. Starting in 1809 Spain's American colonies began a series of revolutions and declared independence, leading to the Spanish American wars of independence that ended Spanish control over its mainland colonies in the Americas. King Ferdinand VII's attempt to re-assert control proved futile as he faced opposition not only in the colonies but also in Spain and army revolts followed, led by liberal officers. By the end of 1826, the only American colonies Spain held were Cuba and Puerto Rico.

The Napoleonic War left Spain economically ruined, deeply divided and politically unstable. In the 1830s and 1840s Anti-liberal forces known as Carlists fought against liberals in the Carlist Wars. Liberal forces won, but the conflict between progressive and conservative liberals ended in a weak early constitutional period. After the Glorious Revolution of 1868 and the short-lived First Spanish Republic, a more stable monarchic period began characterised by the practice of turnismo (the rotation of government control between progressive and conservative liberals within the Spanish government).

.jpg)

In the late 19th century nationalist movements arose in the Philippines and Cuba. In 1895 and 1896 the Cuban War of Independence and the Philippine Revolution broke out and eventually the United States became involved. The Spanish–American War was fought in the spring of 1898 and resulted in Spain losing the last of its once vast colonial empire outside of North Africa. El Desastre (the Disaster), as the war became known in Spain, gave added impetus to the Generation of 98 who were conducting an analysis of the country.

Although the period around the turn of the century was one of increasing prosperity, the 20th century brought little peace; Spain played a minor part in the scramble for Africa, with the colonisation of Western Sahara, Spanish Morocco and Equatorial Guinea. It remained neutral during World War I (see Spain in World War I). The heavy losses suffered during the Rif War in Morocco brought discredit to the government and undermined the monarchy.

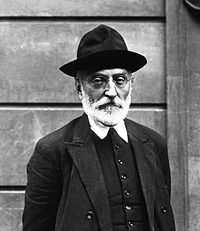

A period of authoritarian rule under General Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923–1931) ended with the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic. The Republic offered political autonomy to the linguistically distinct regions of Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia and gave voting rights to women and was increasingly dominated by left wing political parties. In the worsening economic situation of the Great Depression, Spanish politics became increasingly chaotic and violent.

Spanish Civil War and dictatorship

The Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936. For three years the Nationalist forces led by General Francisco Franco and supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy fought the Republican side, which was supported by the Soviet Union, Mexico and International Brigades but it was not supported by the Western powers due to the British-led policy of Non-Intervention. The civil war was viciously fought and there were many atrocities committed by all sides. The war claimed the lives of over 500,000 people and caused the flight of up to a half-million citizens from the country.[47][48] In 1939, General Franco emerged victorious and became a dictator.

The state as established under Franco was nominally neutral in the Second World War, although sympathetic to the Axis. The only legal party under Franco's post civil war regime was the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS, formed in 1937; the party emphasised falangism, a form of fascism that emphasised anti-communism, nationalism and Roman Catholicism. Given Franco's opposition to competing political parties, the party was renamed the National Movement (Movimiento Nacional) in 1949.

After World War II Spain was politically and economically isolated, and was kept out of the United Nations. This changed in 1955, during the Cold War period, when it became strategically important for the US to establish a military presence on the Iberian Peninsula as a counter to any possible move by the Soviet Union into the Mediterranean basin. In the 1960s, Spain registered an unprecedented rate of economic growth which was propelled by industrialisation, a mass internal migration from rural areas to cities and the creation of a mass tourism industry. Franco's rule was also characterised by authoritarianism, promotion of a unitary national identity, the favouring of a very conservative form of Roman Catholicism known as National Catholicism, and discriminatory language policies.

Democratic restoration

In 1962, Salvador de Madariaga, founder of the Liberal International and the College of Europe, met in the congress of the European Movement in Munich with members of the opposition to Franco's regime inside the country and in the exile. There were 118 politicians from all factions. At the end of the meetings a resolution in favour of democracy was made.[49][50][51]

With Franco's death in November 1975, Juan Carlos succeeded to the position of King of Spain and head of state in accordance with the law. With the approval of the new Spanish Constitution of 1978 and the restoration of democracy, the State devolved much authority to the regions and created an internal organisation based on autonomous communities.

In the Basque Country, moderate Basque nationalism has coexisted with a radical nationalist movement led by the armed organisation ETA. The group was formed in 1959 during Franco's rule but has continued to wage its violent campaign even after the restoration of democracy and the return of a large measure of regional autonomy. On 23 February 1981, rebel elements among the security forces seized the Cortes in an attempt to impose a military backed government. King Juan Carlos took personal command of the military and successfully ordered the coup plotters, via national television, to surrender.

.jpg)

During the 1980s the democratic restoration made possible a growing open society. New cultural movements based on freedom appeared, like La Movida Madrileña. On 30 May 1982 Spain joined NATO, following a referendum. That year the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) came to power, the first left-wing government in 43 years. In 1986 Spain joined the European Economic Community, which later became the European Union. The PSOE was replaced in government by the Partido Popular (PP) after the latter won the 1996 General Elections; at that point the PSOE had served almost 14 consecutive years in office.

On 1 January 2002, Spain fully adopted the euro, and Spain experienced strong economic growth, well above the EU average during the early 2000s. However, well publicised concerns issued by many economic commentators at the height of the boom warned that extraordinary property prices and a high foreign trade deficits were likely to lead to a painful economic collapse.[52]

On 11 March 2004 a local Islamist terrorist group inspired by Al-Qaeda carried out the largest terrorist attack in Spanish history when they killed 191 people and wounded more than 1,800 others by bombing commuter trains in Madrid.[53] Though initial suspicions focused on the Basque group ETA, evidence soon emerged indicating Islamist involvement. Because of the proximity of the 2004 election, the issue of responsibility quickly became a political controversy, with the main competing parties PP and PSOE exchanging accusations over the handling of the incident.[54] At 14 March elections, PSOE, led by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, obtained a plurality, enough to form a new cabinet with Rodríguez Zapatero as the new Presidente del Gobierno or Prime Minister of Spain, thus succeeding the former PP administration.[55]

The proportion of Spain's foreign born population increased rapidly from around 1 in 50 in 2000 to almost 1 in 8 in 2010 but has since declined. In 2005 the Spanish government legalised same sex marriage. The bursting of the Spanish property bubble in 2008 led to the 2008–14 Spanish financial crisis and high levels of unemployment, cuts in government spending, resurgent Catalan nationalism and the Arab Spring served as a backdrop to the 2011–12 Spanish protests. In 2011 Mariano Rajoy's conservative People's Party won elections with 44.6% of votes and Rajoy became the Spanish Prime Minister after having been the leader of the opposition from 2004 to 2011. On 19 June 2014, the monarch, Juan Carlos, abdicated in favour of his son, who became Felipe VI.

Geography

At 505,992 km2 (195,365 sq mi), Spain is the world's fifty-second largest country and Europe's fourth largest country. It is some 47,000 km2 (18,000 sq mi) smaller than France and 81,000 km2 (31,000 sq mi) larger than the US state of California. Mount Teide (Tenerife) is the highest mountain peak in Spain and is the third largest volcano in the world from its base.

Spain lies between latitudes 26° and 44° N, and longitudes 19° W and 5° E.

On the west, Spain borders Portugal; on the south, it borders Gibraltar (a British overseas territory) and Morocco, through its exclaves in North Africa (Ceuta and Melilla, and the peninsula of Vélez de la Gomera). On the northeast, along the Pyrenees mountain range, it borders France and the Principality of Andorra. Along the Pyrenees in Girona, a small exclave town called Llívia is surrounded by France.

Islands

Spain also includes the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea, the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean and a number of uninhabited islands on the Mediterranean side of the Strait of Gibraltar, known as plazas de soberanía ("places of sovereignty", or territories under [Spanish] sovereignty), such as the Chafarinas Islands and Alhucemas. The peninsula of Vélez de la Gomera is also regarded as a plaza de soberanía. The isle of Alborán, located in the Mediterranean between Spain and North Africa, is also administered by Spain, specifically by the municipality of Almería, Andalusia. The little Pheasant Island in the River Bidasoa is a Spanish-French condominium.

List of inhabited islands of Spain:

| Island | Population |

|---|---|

| Tenerife | 899,833 |

| Majorca (Mallorca) | 862,397 |

| Gran Canaria | 838,397 |

| Lanzarote | 141,938 |

| Ibiza | 125,053 |

| Fuerteventura | 103,107 |

| Minorca (Menorca) | 92,434 |

| La Palma | 85,933 |

| La Gomera | 22,259 |

| El Hierro | 10,558 |

| Formentera | 7,957 |

| Arousa | 4,889 |

| La Graciosa | 658 |

| Tabarca | 105 |

| Ons | 61 |

Mountains and rivers

Mainland Spain is a mountainous country, dominated by high plateaus and mountain chains. After the Pyrenees, the main mountain ranges are the Cordillera Cantábrica (Cantabrian Range), Sistema Ibérico (Iberian System), Sistema Central (Central System), Montes de Toledo, Sierra Morena and the Sistema Bético (Baetic System) whose highest peak, the 3,478 m high Mulhacén, located in Sierra Nevada, is the highest elevation in the Iberian Peninsula. The highest point in Spain is the Teide, a 3,718-metre (12,198 ft) active volcano in the Canary Islands. The Meseta Central (often translated as "Inner Plateau") is a vast plateau in the heart of peninsular Spain.

There are several major rivers in Spain such as the Tagus (Tajo), Ebro, Guadiana, Douro (Duero), Guadalquivir, Júcar, Segura, Turia and Minho (Miño). Alluvial plains are found along the coast, the largest of which is that of the Guadalquivir in Andalusia.

Climate

Three main climatic zones can be separated, according to geographical situation and orographic conditions:[56][57][58]

- The Mediterranean climate, characterised by warm and dry summers. It is dominant in the peninsula, with two varieties: Csa and Csb according to the Köppen climate classification. The Csb Zone, with a more extreme climate, hotter in summer and colder in winter, extends to additional areas not typically associated with a Mediterranean climate, such as much of central and northern-central of Spain (e.g. Valladolid, Burgos, León).

- The semi-arid climate (Bsh, Bsk), located in the southeastern quarter of the country, especially in the region of Murcia and in the Ebro valley. In contrast with the Mediterranean climate, the dry season extends beyond the summer.

- The oceanic climate (Cfb), located in the northern quarter of the country, especially in the region of Basque Country, Cantabria, Asturias and partly Galicia. In contrary to the Mediterranean climate, winter and summer temperatures are influenced by the ocean, and have no seasonal drought.

Apart from these main types, other sub-types can be found, like the alpine climate in the Pyrenees and Sierra Nevada, and a typical subtropical climate in the Canary Islands.

The below-listed list covers the average temperatures of the four largest cities of Spain; Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Seville. More information regarding temperature can be found in city articles and the main article about the Spanish climate.

| Location | Coldest month | April | Warmest month | October |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid | 9.8 °C (49.6 °F) 2.7 °C (36.9 °F) |

18.2 °C (64.8 °F) 7.7 °C (45.9 °F) |

32.1 °C (89.8 °F) 19.0 °C (66.2 °F) |

19.4 °C (66.9 °F) 10.7 °C (51.3 °F) |

| Barcelona | 13.6 °C (56.5 °F) 4.7 °C (40.5 °F) |

18.0 °C (64.4 °F) 9.4 °C (48.9 °F) |

28.5 °C (83.3 °F) 20.2 °C (68.4 °F) |

22.1 °C (71.8 °F) 13.5 °C (56.3 °F) |

| Valencia | 16.4 °C (61.5 °F) 7.1 °C (44.8 °F) |

20.8 °C (69.4 °F) 11.5 °C (52.7 °F) |

30.2 °C (86.4 °F) 21.9 °C (71.4 °F) |

24.3 °C (75.7 °F) 15.2 °C (59.4 °F) |

| Seville | 16.0 °C (60.8 °F) 5.7 °C (42.3 °F) |

23.4 °C (74.1 °F) 11.1 °C (52.0 °F) |

36.0 °C (96.8 °F) 20.3 °C (68.5 °F) |

26.0 °C (78.8 °F) 14.4 °C (57.9 °F) |

Governance

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 is the culmination of the Spanish transition to democracy. The constitutional history of Spain dates back to the constitution of 1812. Impatient with the slow pace of democratic political reforms in 1976 and 1977, Spain's new King Juan Carlos, known for his formidable personality, dismissed Carlos Arias Navarro and appointed the reformer Adolfo Suárez as Prime Minister.[60][61] The resulting general election in 1977 convened the Constituent Cortes (the Spanish Parliament, in its capacity as a constitutional assembly) for the purpose of drafting and approving the constitution of 1978.[62] After a national referendum on 6 December 1978, 88% of voters approved of the new constitution.

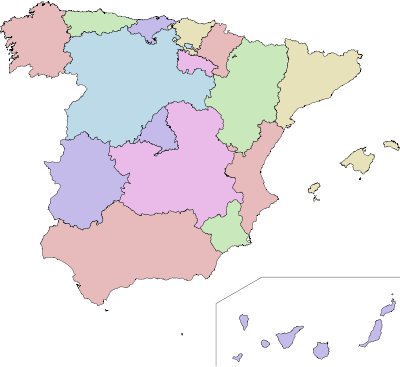

As a result, Spain is now composed of 17 autonomous communities and two autonomous cities with varying degrees of autonomy thanks to its Constitution, which nevertheless explicitly states the indivisible unity of the Spanish nation. The constitution also specifies that Spain has no state religion and that all are free to practice and believe as they wish.

As of November 2009, the government of Spain keeps a balanced gender equality ratio. Nine out of the 18 members of the government are women. Under the administration of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, Spain has been described as being "at the vanguard" in gender equality issues and also that "[n]o other modern, democratic, administration outside Scandinavia has taken more steps to place gender issues at the centre of government".[63]

The Spanish administration has also promoted gender-based positive discrimination by approving gender equality legislation in 2007 aimed at providing equality between genders in Spanish political and economic life (Gender Equality Act).[64][65] However, in the legislative branch, as of July 2010 only 128 of the 350 members of the Congress are women (36.3%).[66] It places Spain 13th on a list of countries ranked by proportion of women in the lower house. In the Senate, the ratio is even lower, since there are only 79 women out of 263 (30.0%).[67] The Gender Empowerment Measure of Spain in the United Nations Human Development Report is 0.794, 12th in the world.[68]

Branches of government

Spain is a constitutional monarchy, with a hereditary monarch and a bicameral parliament, the Cortes Generales (General Courts). The executive branch consists of a Council of Ministers of Spain presided over by the Prime Minister, nominated and appointed by the monarch and confirmed by the Congress of Deputies following legislative elections. By political custom established by King Juan Carlos since the ratification of the 1978 Constitution, the king's nominees have all been from parties who maintain a plurality of seats in the Congress.

The legislative branch is made up of the Congress of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados) with 350 members, elected by popular vote on block lists by proportional representation to serve four-year terms, and a Senate (Senado) with 259 seats of which 208 are directly elected by popular vote and the other 51 appointed by the regional legislatures to also serve four-year terms.

- Head of State

- Head of Government

- Prime Minister of Spain (Presidente del Gobierno, literally President of the Government): Mariano Rajoy Brey, elected 20 November 2011.

- Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for the Presidency: Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría.

- Prime Minister of Spain (Presidente del Gobierno, literally President of the Government): Mariano Rajoy Brey, elected 20 November 2011.

- Cabinet

- Council of Ministers (Consejo de Ministros) designated by the Prime Minister.

Spain is organisationally structured as a so-called Estado de las Autonomías ("State of Autonomies"); it is one of the most decentralised countries in Europe, along with Switzerland, Germany and Belgium;[69] for example, all Autonomous Communities have their own elected parliaments, governments, public administrations, budgets, and resources. Health and education systems among others are managed regionally, and in addition, the Basque Country and Navarre also manage their own public finances based on foral provisions. In Catalonia and the Basque Country, a full-fledged autonomous police corps replaces some of the State police functions (see Mossos d'Esquadra, Ertzaintza, Policía Foral and Policía Canaria).

Human Rights

The Government respects the human rights of its citizens; although there are a few problems in some areas, the law and judiciary provide effective means of addressing individual instances of abuse. There are allegations that a few members of the security forces abused detainees and mistreated foreigners and illegal immigrants. According to Amnesty International (AI), government investigations of such alleged abuses are often lengthy and punishments were light. Violence against women was a problem, which the Government took steps to address.

Spain provides one of the highest degrees of liberty in the world for its LGBT community. Among the countries studied by Pew Research Center in 2013, Spain is rated first in acceptance of homosexuality, with an 88% of society supporting the gay community compared to 11% who do not.[70]

Administrative divisions

The Spanish State is integrated by 17 autonomous communities and 2 autonomous cities, both groups being the highest or first-order administrative division in the country. Autonomous communities are integrated by provinces, of which there are 50 in total, and in turn, provinces are integrated by municipalities. In Catalonia, two additional divisions exist, the comarques (sing. comarca) and the vegueries (sing. vegueria) both of which have administrative powers; comarques being aggregations of municipalities, and the vegueries being aggregations of comarques. The concept of a comarca exists in all autonomous communities, however, unlike Catalonia, these are merely historical or geographical subdivisions.

Autonomies

La Mancha

Autonomous communities are the first level administrative division in the country. These were created after the 1979 and current constitution came into effect in recognition of the right to self-government to the "nationalities and regions of Spain".[71] Autonomous communities were to be integrated by adjacent provinces with common historical, cultural, and economical traits. This territorial organisation, based on devolution, is known in Spain as the "State of Autonomies".

The basic institutional law of each autonomous community is the Statute of Autonomy. The Statutes of Autonomy establish the name of the community according to its historical identity, the limits of their territories, the name and organisation of the institutions of government and the rights they enjoy according the constitution.[72]

The government of all autonomous communities must be based on a division of powers comprising:

- a Legislative Assembly whose members must be elected by universal suffrage according to the system of proportional representation and in which all areas that integrate the territory are fairly represented;

- a Government Council, with executive and administrative functions headed by a president, elected by the Legislative Assembly and nominated by the King of Spain;

- a Supreme Court of Justice, under the Supreme Court of the State, which head the judicial organisation within the autonomous community.

Catalonia, Galicia and the Basque Country, which identified themselves as "nationalities" were granted self-government through a rapid process. Andalusia also took that denomination in its first Statute of Autonomy, even though it followed the longer process stipulated in the constitution for the rest of the country. Progressively, other communities in revisions to their Statutes of Autonomy have also taken that denomination in accordance to their historical regional identity, such as the Valencian Community,[73] the Canary Islands,[74] the Balearic Islands,[75] and Aragon.[76]

The autonomous communities have wide legislative and executive autonomy, with their own parliaments and regional governments. The distribution of powers may be different for every community, as laid out in their Statutes of Autonomy, since devolution was intended to be asymmetrical. Only two communities—the Basque Country and Navarre—have full fiscal autonomy. Aside of fiscal autonomy, the "historical" nationalities—Andalusia, the Basque Country, Catalonia, and Galicia—were devolved more powers than the rest of the communities, among them the ability of the regional president to dissolve the parliament and call for elections at any time. In addition, the Basque Country, Catalonia and Navarre have police corps of their own: Ertzaintza, Mossos d'Esquadra and the Policía Foral respectively. Other communities have more limited forces or none at all, like the Policía Autónoma Andaluza[77] in Andalusia or the BESCAM in Madrid.

Nonetheless, recent amendments to existing Statutes of Autonomy or the promulgation of new Statutes altogether, have reduced the asymmetry between the powers originally granted to the "historical nationalities" and the rest of the regions.

Finally, along with the 17 autonomous communities, two autonomous cities are also part of the State of Autonomies and are first-order territorial divisions: Ceuta and Melilla. These are two exclaves located in the northern African coast.

Provinces and municipalities

Autonomous communities are subdivided into provinces, which served as their territorial building blocks. In turn, provinces are integrated by municipalities. The existence of both the provinces and the municipalities is guaranteed and protected by the constitution, not necessarily by the Statutes of Autonomy themselves. Municipalities are granted autonomy to manage their internal affairs, and provinces are the territorial divisions designed to carry out the activities of the State.[78]

The current provincial division structure is based—with minor changes—on the 1833 territorial division by Javier de Burgos, and in all, the Spanish territory is divided into 50 provinces. The communities of Asturias, Cantabria, La Rioja, the Balearic Islands, Madrid, Murcia and Navarre are the only communities that are integrated by a single province, which is coextensive with the community itself. In this cases, the administrative institutions of the province are replaced by the governmental institutions of the community.

Foreign relations

After the return of democracy following the death of Franco in 1975, Spain's foreign policy priorities were to break out of the diplomatic isolation of the Franco years and expand diplomatic relations, enter the European Community, and define security relations with the West.

As a member of NATO since 1982, Spain has established itself as a participant in multilateral international security activities. Spain's EU membership represents an important part of its foreign policy. Even on many international issues beyond western Europe, Spain prefers to co-ordinate its efforts with its EU partners through the European political co-operation mechanisms.

Spain has maintained its special relations with Hispanic America and the Philippines. Its policy emphasises the concept of an Ibero-American community, essentially the renewal of the historically liberal concept of "Hispanidad" or "Hispanismo", as it is often referred to in English, which has sought to link the Iberian Peninsula with Hispanic America through language, commerce, history and culture.

Territorial disputes

Spain claims Gibraltar, a 6-square-kilometre (2.3 sq mi) Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom in the southernmost part of the Iberian Peninsula. Then a Spanish town, it was conquered by an Anglo-Dutch force in 1704 during the War of the Spanish Succession on behalf of Archduke Charles, pretender to the Spanish throne.

The legal situation concerning Gibraltar was settled in 1713 by the Treaty of Utrecht, in which Spain ceded the territory in perpetuity to the British Crown[79] stating that, should the British abandon this post, it would be offered to Spain first. Since the 1940s Spain has called for the return of Gibraltar. The overwhelming majority of Gibraltarians strongly oppose this, along with any proposal of shared sovereignty.[80] UN resolutions call on the United Kingdom and Spain, both EU members, to reach an agreement over the status of Gibraltar.[81][82]

The Spanish claim makes a distinction between the isthmus that connects the Rock to the Spanish mainland on the one hand, and the Rock and city of Gibraltar on the other. While the Rock and city were ceded by the Treaty of Utrecht, Spain asserts that the "occupation of the isthmus is illegal and against the principles of International Law".[83] The United Kingdom relies on de facto arguments of possession by prescription in relation to the isthmus,[84] as there has been "continuous possession [of the isthmus] over a long period".[85]

Another claim by Spain is about the Savage Islands, a claim not recognised by Portugal. Spain claims that they are rocks rather than islands, therefore claiming that there is no Portuguese territorial waters around the disputed islands. On 5 July 2013, Spain sent a letter to the UN expressing these views.[86][87]

Spain claims the sovereignty over the Perejil Island, a small, uninhabited rocky islet located in the South shore of the Strait of Gibraltar. The island lies 250 metres (820 ft) just off the coast of Morocco, 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) from Ceuta and 13.5 kilometres (8.4 mi) from mainland Spain. Its sovereignty is disputed between Spain and Morocco. It was the subject of an armed incident between the two countries in 2002. The incident ended when both countries agreed to return to the status quo ante which existed prior to the Moroccan occupation of the island. The islet is now deserted and without any sign of sovereignty.

Besides the Perejil Island, the Spanish-held territories claimed by other countries are two: Morocco claims the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla and the plazas de soberanía islets off the northern coast of Africa; and Portugal does not recognise Spain's sovereignty over the territory of Olivenza.

Military

.jpg)

The armed forces of Spain are known as the Spanish Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas Españolas). Their Commander-in-chief is the King of Spain, Felipe VI.[88]

The Spanish Armed Forces are divided into three branches:[89]

Economy

Recent background

Spain's capitalist mixed economy is the 14th largest worldwide and the 5th largest in the European Union, as well as the Eurozone's 4th largest.

The centre-right government of former prime minister José María Aznar worked successfully to gain admission to the group of countries launching the euro in 1999. Unemployment stood at 7.6% in October 2006, a rate that compared favourably to many other European countries, and especially with the early 1990s when it stood at over 20%. Perennial weak points of Spain's economy include high inflation,[90] a large underground economy,[91] and an education system which OECD reports place among the poorest for developed countries, together with the United States and UK.[92]

By the mid-1990s the economy had recommmenced the growth that had been disrupted by the global recession of the early 1990s. The strong economic growth helped the government to reduce the government debt as a percentage of GDP and Spain's high unemployment began to drop steadily. With the government budget in balance and inflation under control Spain was admitted into the Eurozone in 1999.

Since the 1990s some Spanish companies have gained multinational status, often expanding their activities in culturally close Latin America. Spain is the second biggest foreign investor there, after the United States. Spanish companies have also expanded into Asia, especially China and India.[93] This early global expansion is a competitive advantage over its competitors and European neighbours. The reason for this early expansion is the booming interest toward Spanish language and culture in Asia and Africa and a corporate culture that learned to take risks in unstable markets.

Spanish companies invested in fields like renewable energy commercialisation (Iberdrola was the world's largest renewable energy operator[94]), technology companies like Telefónica, Abengoa, Mondragon Corporation, Movistar, Hisdesat, Indra, train manufacturers like CAF, Talgo, global corporations such as the textile company Inditex, petroleum companies like Repsol and infrastructure, with six of the ten biggest international construction firms specialising in transport being Spanish, like Ferrovial, Acciona, ACS, OHL and FCC.[95]

Property boom and bust

The adoption of the Euro saw a marked reduction in interest rates to historic lows. The growth in the Spanish property market, which had begun in 1997, accelerated and within a few years had developed into a property bubble, financed largely by the cajas (regional savings banks under the oversight of the regional governments) and fed by the historically low interest rates and a massive growth of immigration. The Spanish economy was credited for having avoided the virtual zero growth rate of some of its largest partners in the EU.[96]

Spain's economy created more than half of all the new jobs in the European Union over the five years ending 2005.[97][98] The bubble imploded in 2008, causing the collapse of Spain's large property related and construction sectors, causing mass layoffs, and a collapsing domestic demand for goods and services. By the end of May 2009, unemployment reached 18.7% (37% for youths).[99][100][101]

At first, Spain's banks and financial services avoided the early crisis of their counterparts in the US and UK. This was particularly the case with Spain's international banks, Banco Santander and BBVA, that had diversified, international portfolios and had actively limited their exposure to housing mortgage risk. Banco Santander was able to profit from the global financial crisis by taking over distressed British banking firms.[102] However, as the recession deepened and property prices slid, the growing bad debts of the smaller regional savings banks, the cajas, forced the intervention of Spain's central bank and government through a stabilisation and consolidation program, taking over or consolidating regional cajas and finally receiving a bank bailout from the European Central Bank in 2012.[103][104][105]

Quality of life

In 2005 the Economist Intelligence Unit's quality of life survey placed Spain among the top 10 in the world.[109] In 2013 the same survey (now called the "Where-to-be-born index"), ranked Spain 28th in the world.[110]

In 2010, the Basque city of Bilbao was awarded with the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize,[111] and its mayor at the time, Iñaki Azkuna, was awarded the World Mayor Prize in 2012.[112] The city of Vitoria-Gasteiz received the European Green Capital Award in 2012.[113]

Agriculture

Crop areas were farmed in two highly diverse manners. Areas relying on non-irrigated cultivation (secano), which made up 85% of the entire crop area, depended solely on rainfall as a source of water. They included the humid regions of the north and the northwest, as well as vast arid zones that had not been irrigated. The much more productive regions devoted to irrigated cultivation (regadío) accounted for 3 million hectares in 1986, and the government hoped that this area would eventually double, as it already had doubled since 1950. Particularly noteworthy was the development in Almería—one of the most arid and desolate provinces of Spain—of winter crops of various fruits and vegetables for export to Europe.

Though only about 17% of Spain's cultivated land was irrigated, it was estimated to be the source of between 40-45% of the gross value of crop production and of 50% of the value of agricultural exports. More than half of the irrigated area was planted in corn, fruit trees, and vegetables. Other agricultural products that benefited from irrigation included grapes, cotton, sugar beets, potatoes, legumes, olive trees, mangos, strawberries, tomatoes, and fodder grasses. Depending on the nature of the crop, it was possible to harvest two successive crops in the same year on about 10% of the country's irrigated land.

Citrus fruits, vegetables, cereal grains, olive oil, and wine—Spain's traditional agricultural products—continued to be important in the 1980s. In 1983 they represented 12%, 12%, 8%, 6%, and 4%, respectively, of the country's agricultural production. Because of the changed diet of an increasingly affluent population, there was a notable increase in the consumption of livestock, poultry, and dairy products. Meat production for domestic consumption became the single most important agricultural activity, accounting for 30% of all farm-related production in 1983. Increased attention to livestock was the reason that Spain became a net importer of grains. Ideal growing conditions, combined with proximity to important north European markets, made citrus fruits Spain's leading export. Fresh vegetables and fruits produced through intensive irrigation farming also became important export commodities, as did sunflower seed oil that was produced to compete with the more expensive olive oils in oversupply throughout the Mediterranean countries of the EC.

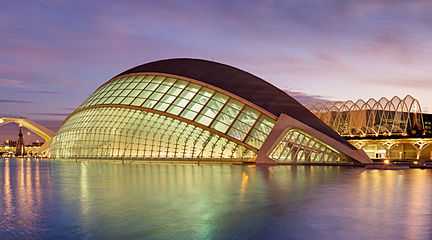

Tourism

The climate of Spain, its geographic location, popular coastlines, diverse landscapes, historical legacy, vibrant culture and excellent infrastructure, has made Spain's international tourist industry among the largest in the world. In the last five decades, international tourism in Spain has grown to become the second largest in the world in terms of spending, worth approximately 40 billion Euros or about 5% of GDP in 2006.[114][115]

Energy

Spain is one of the world's leading countries in the development and production of renewable energy. In 2010 Spain became the solar power world leader when it overtook the United States with a massive power station plant called La Florida, near Alvarado, Badajoz.[117][118] Spain is also Europe's main producer of wind energy. In 2010 its wind turbines generated 42,976 GWh, which accounted for 16.4% of all electrical energy produced in Spain.[119][120][121] On 9 November 2010, wind energy reached an instantaneous historic peak covering 53% of mainland electricity demand[122] and generating an amount of energy that is equivalent to that of 14 nuclear reactors.[123] Other renewable energies used in Spain are hydroelectric, biomass and marine (2 power plants under construction).[124]

Non-renewable energy sources used in Spain are nuclear (8 operative reactors), gas, coal, and oil. Fossil fuels together generated 58% of Spain's electricity in 2009, just below the OECD mean of 61%. Nuclear power generated another 19%, and wind and hydro about 12% each.[125]

Transport

The Spanish road system is mainly centralised, with six highways connecting Madrid to the Basque Country, Catalonia, Valencia, West Andalusia, Extremadura and Galicia. Additionally, there are highways along the Atlantic (Ferrol to Vigo), Cantabrian (Oviedo to San Sebastián) and Mediterranean (Girona to Cádiz) coasts. Spain aims to put one million electric cars on the road by 2014 as part of the government's plan to save energy and boost energy efficiency.[126] The Minister of Industry Miguel Sebastian said that "the electric vehicle is the future and the engine of an industrial revolution."[127]

Spain has the most extensive high-speed rail network in Europe, and the second-most extensive in the world after China.[128][129][130] As of October 2010, Spain has a total of 3,500 km (2,174.80 mi) of high-speed tracks linking Málaga, Seville, Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Valladolid, with the trains reaching speeds up to 300 km/h (190 mph). On average, the Spanish high-speed train is the fastest one in the world, followed by the Japanese bullet train and the French TGV.[131] Regarding punctuality, it is second in the world (98.54% on-time arrival) after the Japanese Shinkansen (99%).[132] Should the aims of the ambitious AVE program (Spanish high speed trains) be met, by 2020 Spain will have 7,000 km (4,300 mi) of high-speed trains linking almost all provincial cities to Madrid in less than three hours and Barcelona within four hours.

There are 47 public airports in Spain. The busiest one is the airport of Madrid (Barajas), with 50 million passengers in 2011, being the world's 15th busiest airport, as well as the European Union's fourth busiest. The airport of Barcelona (El Prat) is also important, with 35 million passengers in 2011, being the world's 31st-busiest airport. Other main airports are located in Majorca (23 million passengers), Málaga (13 million passengers), Las Palmas (Gran Canaria) (11 million passengers), Alicante (10 million passengers) and smaller, with the number of passengers between 4 and 10 million, for example Tenerife (two airports), Valencia, Seville, Bilbao, Ibiza, Lanzarote, Fuerteventura. Also, more than 30 airports with the number of passengers below 4 million.

Demographics

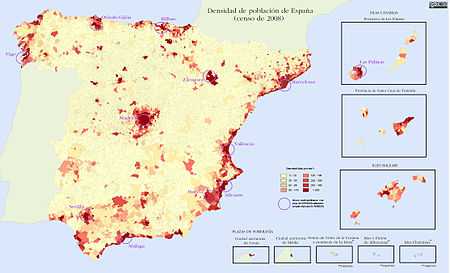

In 2008 the population of Spain officially reached 46 million people, as recorded by the Padrón municipal (Spain's Municipal Register).[133] Spain's population density, at 91/km² (235/sq mi), is lower than that of most Western European countries and its distribution across the country is very unequal. With the exception of the region surrounding the capital, Madrid, the most populated areas lie around the coast. The population of Spain more than doubled since 1900, when it stood at 18.6 million, principally due to the spectacular demographic boom in the 1960s and early 1970s.[134]

Native Spaniards make up 88% of the total population of Spain. After the birth rate plunged in the 1980s and Spain's population growth rate dropped, the population again trended upward, based initially on the return of many Spaniards who had emigrated to other European countries during the 1970s, and more recently, fuelled by large numbers of immigrants who make up 12% of the population. The immigrants originate mainly in Latin America (39%), North Africa (16%), Eastern Europe (15%), and Sub-Saharan Africa (4%).[135] In 2005, Spain instituted a three-month amnesty program through which certain hitherto undocumented aliens were granted legal residency.

In 2008, Spain granted citizenship to 84,170 persons, mostly to people from Ecuador, Colombia and Morocco.[136] A sizeable portion of foreign residents in Spain also comes from other Western and Central European countries. These are mostly British, French, German, Dutch, and Norwegian. They reside primarily on the Mediterranean coast and the Balearic islands, where many choose to live their retirement or telecommute.

Substantial populations descended from Spanish colonists and immigrants exist in other parts of the world, most notably in Latin America. Beginning in the late 15th century, large numbers of Iberian colonists settled in what became Latin America and at present most white Latin Americans (who make up about one-third of Latin America's population) are of Spanish or Portuguese origin. Around 240,000 Spaniards emigrated in the 16th century, mostly to Peru and Mexico.[137] Another 450,000 left in the 17th century.[138] Between 1846 and 1932 it is estimated that nearly 5 million Spaniards emigrated to the Americas, especially to Argentina and Brazil.[139] Approximately two million Spaniards migrated to other Western European countries between 1960 and 1975. During the same period perhaps 300,000 went to Latin America.[140]

Urbanisation

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Autonomous community | Pop. | Rank | Name | Autonomous community | Pop. | ||

Madrid Barcelona |

1 | Madrid | Madrid | 3,165,235 | 11 | Alicante | Valencia | 332,067 |  Valencia  Seville |

| 2 | Barcelona | Catalonia | 1,620,943 | 12 | Córdoba | Andalusia | 328,041 | ||

| 3 | Valencia | Valencia | 786,424 | 13 | Valladolid | Castile and León | 306,830 | ||

| 4 | Seville | Andalusia | 696,676 | 14 | Vigo | Galicia | 294,997 | ||

| 5 | Zaragoza | Aragon | 666,058 | 15 | Gijón | Asturias | 275,735 | ||

| 6 | Málaga | Andalusia | 566,913 | 16 | L'Hospitalet | Catalonia | 253,518 | ||

| 7 | Murcia | Murcia | 439,712 | 17 | A Coruña | Galicia | 244,810 | ||

| 8 | Palma | Balearic Islands | 399,093 | 18 | Vitoria-Gasteiz | Basque Country | 242 092 | ||

| 9 | Las Palmas | Canary Islands | 382,283 | 19 | Granada | Andalusia | 237,540 | ||

| 10 | Bilbao | Basque Country | 347,574 | 20 | Elche | Valencia | 228,647 | ||

Metropolitan areas

Source: "Áreas urbanas +50", Ministry of Public Works and Transport (2013)[141]

| Rank | Metro area | Autonomous community |

Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government data | Other estimations | |||

| 1 | Madrid | Madrid | 6,052,247 | 5.4 – 6.5 m[142][143] |

| 2 | Barcelona | Catalonia | 5,030,679 | 4.2 – 5.1 m[142][144] |

| 3 | Valencia | Valencia | 1,551,585 | 1.5 – 2.3 m[145] |

| 4 | Seville | Andalusia | 1,294,867 | 1.2 – 1.3 m |

| 5 | Málaga | Andalusia | 953,251 | |

| 6 | Bilbao | Basque Country | 910,578 | |

| 7 | Oviedo–Gijón–Avilés | Asturias | 835,053 | |

| 8 | Zaragoza | Aragon | 746,152 | |

| 9 | Alicante–Elche | Valencia | 698,662 | |

| 10 | Murcia | Murcia | 643,854 | |

Peoples

The Spanish Constitution of 1978, in its second article, recognises historic entities—nationalities (a carefully chosen word to avoid the more politically charged "nations")—and regions, within the context of the Spanish nation. For some people, Spain's identity consists more of an overlap of different regional identities than of a sole Spanish identity. Indeed, some of the regional identities may even conflict with the Spanish one. Distinct traditional regional identities within Spain include the Basques, Catalans, Galicians, Cantabrians and Castilians, among others.[146]

It is this last feature of "shared identity" between the more local level or Autonomous Community and the Spanish level which makes the identity question in Spain complex and far from univocal.

Minority groups

Spain has a number of descendants of populations from former colonies, especially Latin America and North Africa. Smaller numbers of immigrants from several Sub-Saharan countries have recently been settling in Spain. There are also sizeable numbers of Asian immigrants, most of whom are of Middle Eastern, South Asian and Chinese origin. The single largest group of immigrants are European; represented by large numbers of Britons, Germans, French and others.[147]

The arrival of the gitanos, a Romani people, began in the 16th century; estimates of the Spanish Gitano population fluctuate around 700,000.[148] There are also the mercheros (also quinquis), a formerly nomadic minority group. Their origin is unclear.

Historically, Sephardi Jews and moriscos are the main minority groups originated in Spain and with a contribution to Spanish culture.[149] The Spanish government is offering Spanish nationality to sephardi Jews.[150]

Immigration

According to the Spanish government there were 5.7 million foreign residents in Spain in 2011, or 12% of the total population. According to residence permit data for 2011, more than 860,000 were Romanian, about 770,000 were Moroccan, approximately 390,000 were British, and 360,000 were Ecuadorian.[151] Other sizeable foreign communities are Colombian, Bolivian, German, Italian, Bulgarian, and Chinese. There are more than 200,000 migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa living in Spain, principally Senegaleses and Nigerians.[152] Since 2000, Spain has experienced high population growth as a result of immigration flows, despite a birth rate that is only half the replacement level. This sudden and ongoing inflow of immigrants, particularly those arriving illegally by sea, has caused noticeable social tension.[153]

Within the EU, Spain had the 2nd highest immigration rate in percentage terms after Cyprus, but by a great margin, the highest in absolute numbers, up to 2008.[154] The number of immigrants in Spain had grown up from 500,000 people in 1996 to 5.2 million in 2008 out of a total population of 46 million.[155][156] In 2005 alone, a regularisation programme increased the legal immigrant population by 700,000 people.[157] There are a number of reasons for the high level of immigration, including Spain's cultural ties with Latin America, its geographical position, the porosity of its borders, the large size of its underground economy and the strength of the agricultural and construction sectors, which demand more low cost labour than can be offered by the national workforce.

Another statistically significant factor is the large number of residents of EU origin typically retiring to Spain's Mediterranean coast. In fact, Spain was Europe's largest absorber of migrants from 2002 to 2007, with its immigrant population more than doubling as 2.5 million people arrived.[158] In 2008, prior to the onset of the economic crisis, the Financial Times reported that Spain was the most favoured destination for Western Europeans considering a move from their own country and seeking jobs elsewhere in the EU.[159]

In 2008, the government instituted a "Plan of Voluntary Return" which encouraged unemployed immigrants from outside the EU to return to their home countries and receive several incentives, including the right to keep their unemployment benefits and transfer whatever they contributed to the Spanish Social Security.[160] The program had little effect; during its first two months, just 1,400 immigrants took up the offer.[161] What the program failed to do, the sharp and prolonged economic crisis has done from 2010 to 2011 in that tens of thousands of immigrants have left the country due to lack of jobs. In 2011 alone, more than half a million people left Spain.[162] For the first time in decades the net migration rate was expected to be negative, and nine out of 10 emigrants were foreigners.[162]

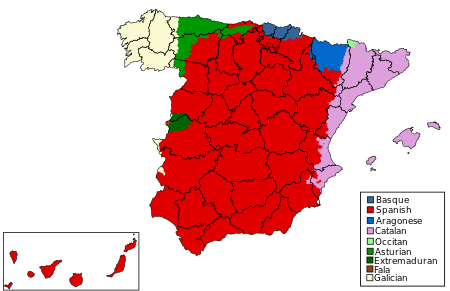

Languages

Spain is openly multilingual,[163] and the constitution establishes that the nation will protect "all Spaniards and the peoples of Spain in the exercise of human rights, their cultures and traditions, languages and institutions.[164]

Spanish (español)—officially recognised in the constitution as Castilian (castellano)—is the official language of the entire country, and it is the right and duty of every Spaniard to know the language. The constitution also establishes that "all other Spanish languages"—that is, all other languages of Spain—will also be official in their respective autonomous communities in accordance to their Statutes, their organic regional legislations, and that the "richness of the distinct linguistic modalities of Spain represents a patrimony which will be the object of special respect and protection."[165]

The other official languages of Spain, co-official with Spanish are:

- Basque (euskara) in the Basque Country and Navarre;

- Catalan (català) in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and in the Valencian Community, where its distinct modality of the language is officially known as Valencian (valencià); and

- Galician (galego) in Galicia

As a percentage of the general population, Basque is spoken by 2%, Catalan (or Valencian) by 17%, and Galician by 7% of all Spaniards.[166]