Space habitat

| Space colonization |

|---|

|

Core concepts

Colonization and terraforming

Organizations |

A space habitat (also called a space colony, space settlement or orbital colony) is a type of space station, intended as a permanent settlement rather than as a simple way-station or other specialized facility. No space habitats have yet been constructed but many design proposals have been made, with varying degrees of realism, by both engineers and science fiction authors.

The term space habitat is sometimes used more broadly to include colonies built on the surface of a body other than Earth, such as the Moon, Mars or an asteroid. This article concentrates on self-contained structures built in microgravity.

Motivation

Several motivations for building space colonies have been proposed:

- Survival of human civilization and the biosphere, in case of a disaster on the Earth (natural or man-made)[1]

- Huge resources in space for expansion of human society

- Expansion without any ecosystems to destroy or indigenous peoples to displace

- It could help the Earth by relieving population pressure and taking industry off-Earth.

(See: Reasons for space colonization.)

Advantages of space habitats

A number of arguments are made for space habitats having a number of advantages:

Access to solar energy

Space has an abundance of light produced from the Sun. In Earth orbit, this amounts to 1400 watts of power per square meter.[2] This energy can be used to produce electricity from solar cells or heat engine based power stations, process ores, provide light for plants to grow and to warm space colonies.

Habitats would have constant access to solar energy up to very large distances from the Sun. Weightlessness allows the construction of large flimsy structures. The ECHO-1 satellite was a balloon for reflecting microwaves that weighed 66 kg and was 41.1 meters in diameter. It also reflected sunlight.[3] Concentrating sunlight with mirrors is a source of power.

Outside gravity well

Earth-to-space habitat trade would be easier than Earth-to-planetary colony trade, as colonies orbiting Earth will not have a gravity well to overcome to export to Earth, and a smaller gravity well to overcome to import from Earth.

In-situ resource utilization

Space habitats may be supplied with resources from extraterrestrial places like Mars, asteroids, or the Moon (in-situ resource utilization [ISRU];[1] see Asteroid mining). One could produce breathing oxygen, drinking water, and rocket fuel with the help of ISRU.[1] It may become possible to manufacture solar panels from Lunar materials.[1]

Asteroids and other small bodies

Most asteroids are a mixture of materials, virtually all stable elements on the periodic table can be found in the asteroids and comets and more importantly, because these bodies do not have substantial gravity wells, it is very easy to draw materials from them and haul them to a construction site.[4]

There is estimated to be enough material in the main asteroid belt alone to build enough space habitats to equal the habitable surface area of 3,000 Earths.[5]

Population

Habitats may be constructed to give an immense total population capacity. Using the free-floating resources of the solar system, current estimates extend into the trillions.[6]

Zero g recreation

If the station is equipped with zero g facilities, weightlessness enables the creation of zero g swimming pools and stadiums,[7][8] infinite hang gliding flights [9] and the use of Human-powered aircraft.

Passenger compartment

A space habitat can be the passenger compartment of a large spacecraft for colonizing asteroids, moons, and planets. It can also function as one for a generation ship for travel to distant stars (L. R. Shepherd described a generation starship in 1952 comparing it to a small planet with many people living in it.[10][11]) or other planets (see: Space and survival).

Requirements

The requirements for a space habitat are many. They would have to provide all the material needs for hundreds or thousands of humans, in an environment out in space that is very hostile to human life.

Atmosphere

Air pressure, with normal partial pressures of oxygen, carbon dioxide and nitrogen, is a basic requirement of any space habitat. Basically, most space colony designs propose large, thin-walled pressure vessels. The required oxygen could be obtained from lunar rock. Nitrogen is most easily available from the Earth, but is also recycled nearly perfectly. Also, nitrogen in the form of ammonia may be obtainable from comets and the moons of outer planets. Nitrogen may also be available in unknown quantities on certain other bodies in the outer solar system. The air of a colony could be recycled in a number of ways. The most obvious method is to use photosynthetic gardens, possibly via hydroponics, or forest gardening. However, these do not remove certain industrial pollutants, such as volatile oils, and excess simple molecular gases. The standard method used on nuclear submarines, a similar form of closed environment, is to use a catalytic burner, which effectively removes most organics. Further protection might be provided by a small cryogenic distillation system which would gradually remove impurities such as mercury vapor, and noble gases that cannot be catalytically burned.

Food production

Organic materials for food production would also need to be provided. At first, most of these would have to be imported from the moon, asteroids, or the Earth. After that, recycling should reduce the need for imports. One proposed recycling method would start by burning the cryogenic distillate, plants, garbage and sewage with air in an electric arc, and distilling the result. The resulting carbon dioxide and water would be immediately usable in agriculture. The nitrates and salts in the ash could be dissolved in water and separated into pure minerals. Most of the nitrates, potassium and sodium salts would effectively recycle as fertilizers. Other minerals containing iron, nickel, and silicon could be chemically purified in batches and reused industrially. The small fraction of remaining materials, well below 0.01% by weight, could be processed into pure elements with zero-gravity mass spectrometry, and added in appropriate amounts to the fertilizers and industrial stocks. This method's only current existence is a proof considered by NASA studies. It's likely that methods would be greatly refined as people began to actually live in space habitats.

Artificial gravity

Long-term on-orbit studies have proven that zero gravity weakens bones and muscles, and upsets calcium metabolism and immune systems. Most people have a continual stuffy nose or sinus problems, and a few people have dramatic, incurable motion sickness. Most colony designs would rotate in order to use inertial forces to simulate gravity. NASA studies with chickens and plants have proven that this is an effective physiological substitute for gravity. Turning one's head rapidly in such an environment causes a "tilt" to be sensed as one's inner ears move at different rotational rates. Centrifuge studies show that people get motion-sick in habitats with a rotational radius of less than 100 metres, or with a rotation rate above 3 rotations per minute. However, the same studies and statistical inference indicate that almost all people should be able to live comfortably in habitats with a rotational radius larger than 500 meters and below 1 RPM. Experienced persons were not merely more resistant to motion sickness, but could also use the effect to determine "spinward" and "antispinward" directions in the centrifuges.

Protection from radiation

Some very large space habitat designs could be effectively shielded from cosmic rays by their structure and air. Smaller habitats could be shielded by stationary (nonrotating) bags of rock. Sunlight could be admitted indirectly via mirrors in radiation-proof louvres, which would function in the same manner as a periscope.

- For instance, 4 metric tons per square meter of surface area could reduce radiation dosage to several mSv or less annually, below the rate of some populated high natural background areas on Earth.[12] Alternative concepts based on active shielding are untested yet and more complex than such passive mass shielding, but usage of magnetic and/or electric fields to deflect particles could potentially greatly reduce mass requirements.[13]

- If a space habitat is located at L4 or L5, then its orbit will take it outside of the protection of the Earth's magnetosphere for approximately two-thirds of the time (as happens with the Moon), putting residents at risk of proton exposure from the solar wind.

- See Health threat from cosmic rays

Heat rejection

The colony is in a vacuum, and therefore resembles a giant thermos bottle. The sunlight to radiated energy ratio can be reduced and controlled with large venetian blinds. Habitats also need a radiator to eliminate heat from absorbed sunlight and organisms. Very small habitats might have a central vane that rotates with the colony. In this design, convection would raise hot air "up" (toward the center), and cool air would fall down into the outer habitat. Some other designs would distribute coolants, such as chilled water from a central radiator.

Meteoroids and dust

The habitat would need to withstand potential impacts from space debris, meteoroids, dust, etc. Radar will sweep the space around each habitat mapping the trajectory of debris and other man-made objects and allowing corrective actions to be taken to protect the habitat. Meteoroid strikes would pose a risk to a space habitat much stronger than they do to the Earth, unless there should be developed a method to avert them, because a space habitat does not possess a sheltering atmosphere.

Attitude control

Most mirror geometries require something on the habitat to be aimed at the sun and so attitude control is necessary. The original O'Neill design used the two cylinders as momentum wheels to roll the colony, and pushed the sunward pivots together or apart to use precession to change their angle. Later designs rotated in the plane of their orbit, with their windows pointing at right angles to the sunlight, and used lightweight mirrors that could be steered with small electric motors to follow the sun.

Considerations

Initial capital outlay

Even the smallest of the habitat designs mentioned below is more massive than the total mass of all items ever launched by mankind into Earth orbit. Prerequisites to building habitats are either cheaper launch costs or a mining and manufacturing base on the Moon or other body having low delta-v from the desired habitat location.[4]

Location

The optimal habitat orbits are still debated, and so orbital stationkeeping is probably a commercial issue. The lunar L4 and L5 orbits are now thought to be too far away from the moon and Earth. A more modern proposal is to use a two-to-one resonance orbit that alternately has a close, low-energy (cheap) approach to the moon, and then to the Earth. This provides quick, inexpensive access to both raw materials and the major market. Most colony designs plan to use electromagnetic tether propulsion, or mass drivers used as rocket motors. The advantage of these is that they either use no reaction mass at all, or use cheap reaction mass.

Engineering studies

The High Frontier

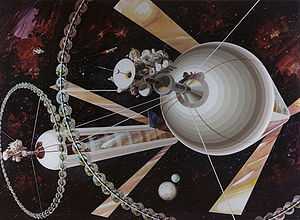

Around 1970, near the end of Project Apollo (1961-1972), Gerard K. O'Neill, an experimental physicist at Princeton University, was looking for a topic to tempt his physics students, most of them freshmen in engineering. He hit upon the idea of assigning them feasibility calculations for large space-habitats. To his surprise, the habitats seemed feasible even in very large sizes: cylinders 8 km (5 mi) in diameter and 32 km (20 mi) long, even if made from ordinary materials such as steel and glass. Also, the students solved problems such as radiation protection from cosmic rays (almost free in the larger sizes), getting naturalistic sun angles, provision of power, realistic pest-free farming and orbital attitude control without reaction motors. O'Neill published an article about these colony proposals in Physics Today in 1974.[6] (See the above illustration of such a colony, a classic "O'Neill Colony"). He expanded the article in his 1976 book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space.

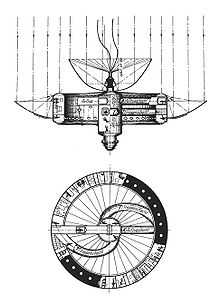

NASA Ames/Stanford 1975 Summer Study

The result motivated NASA to sponsor a couple of summer workshops led by Dr. O'Neill.[14][15] Several designs were studied, some in depth, with sizes ranging from 1,000 to 10,000,000 people.[4][16][17]

O'Neill's proposal had an example of a payback scheme: construction of solar power satellites from lunar materials. O'Neill did not emphasize the building of solar power satellites as such, but rather offered proof that orbital manufacturing from lunar materials could generate profits. He and other participants presumed that once such manufacturing facilities had started production, many profitable uses for them would be found, and the colony would become self-supporting and begin to build other colonies as well.

The proposals and studies generated a notable groundswell of public interest. One effect of this expansion was the founding of the L5 Society in the U.S., a group of enthusiasts that desired to build and live in such colonies. The group was named after the space-colony orbit which was then believed to be the most profitable, a kidney-shaped orbit around either of Earth's lunar Lagrange points 5 or 4.

Space Studies Institute

In 1977 Dr. O'Neill founded the quieter and more targeted Space Studies Institute, which initially funded and constructed prototypes of much of the radically new hardware needed for a space colonization effort, as well as producing a number of paper studies of feasibility. One of the early projects, for instance, involved a series of functional prototypes of a mass driver, the essential technology for moving ores economically from the Moon to space-colony orbits.

In Fiction

The space habitats have inspired a large number of fictional societies in science fiction. Some of the most popular and recognizable are in the Japanese Gundam universe, the space station Deep Space Nine and the space station Babylon 5.

Designs/solutions

NASA designs

Designs proposed in NASA studies included:

- Bernal sphere: "Island One", a spherical habitat for about 20,000 people.

- Stanford torus: A larger alternative to "Island One."

- O'Neill cylinder: "Island Three" (pictured), an even larger design.

- Lewis One:[18] A cylinder of radius 250 m with a non rotating radiation shielding. The shielding protects the micro-gravity industrial space, too. The rotating part is 450m long and has several inner cylinders. Some of them are used for agriculture.

- Kalpana One, revised:[8] A short cylinder with 250 m radius and 325 m length. The radiation shielding is 10 t/m2 and rotates. It has several inner cylinders for agriculture and recreaction.[19][20]

- A bola: a spacecraft or habitat connected by a cable to a counterweight or other habitat. This design has been proposed as a Mars ship, initial construction shack for a space habitat, and orbital hotel. It has a comfortably long and slow rotational radius for a relatively small station mass. Also, if some of the equipment can form the counter-weight, the equipment dedicated to artificial gravity is just a cable, and thus has a much smaller mass-fraction than in other designs. This makes it a tempting design for a deep-space ship. For a long-term habitation, however, radiation shielding must rotate with the habitat, and is extremely heavy, thus requiring a much stronger and heavier cable..[21]

- Beaded habitats:[21] This speculative design was also considered by the NASA studies, and found to have a roughly equivalent mass fraction of structure and therefore comparable costs. Small habitats would be mass-produced to standards that allow the habitats to interconnect. A single habitat can operate alone as a bola. However, further habitats can be attached, to grow into a "dumbbell" then a "bow-tie," then a ring, then a cylinder of "beads," and finally a framed array of cylinders. Each stage of growth shares more radiation shielding and capital equipment, increasing redundancy and safety while reducing the cost per person. This design was originally proposed by a professional architect because it can grow much like Earth-bound cities, with incremental individual investments, unlike designs that require large start-up investments. The main disadvantage is that the smaller versions use a large amount of structure to support the radiation shielding, which rotates with them. In large sizes, the shielding becomes economical, because it grows roughly as the square of the colony radius. The number of people, their habitats and the radiators to cool them grow roughly as the cube of the colony radius.

Other designs

- Bubbleworld: The Bubbleworld or Inside/Outside concept was originated by Dandridge M. Cole in 1964.[22] The concept calls for drilling a tunnel through the longest axis of a large asteroid of iron or nickel-iron composition and filling it with a volatile substance, possibly water. A very large solar reflector would be constructed nearby, focusing solar heat onto the asteroid, first to weld and seal the tunnel ends, then more diffusely to slowly heat the entire outer surface. As the metal softens, the water inside expands and inflates the mass, while rotational forces help shape it into a cylindrical form. Once expanded and allowed to cool, it can be spun to produce artificial gravity, and the interior filled with soil, air and water. By creating a slight bulge in the middle of the cylinder, a ring-shaped lake can be made to form. Reflectors will allow sunlight to enter and to be directed where needed. Clearly, this method would require a significant human and industrial presence in space to be at all feasible. The concept was popularized by science fiction author Larry Niven in his Known Space stories, describing such worlds as the primary habitats of the Belters, a civilization who had colonized the Asteroid Belt.

- Asteroid Terrarium: a similar idea to the bubbleworld, the asteroid terrarium, appears in the book '2312', authored by hard science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson.

- Bishop Ring: a speculative design using carbon nanotubes, a Bishop Ring is a torus 1000 km in radius, 500 km in width, and with atmosphere retention walls 200 km in height. The design would be large enough that it could be "roofless", open to space on the inner rim.[23]

- McKendree cylinder: another speculative design made of carbon nanotubes, a McKendree cylinder is paired cylinders in the same vein as the Island Three design, but each 460 km in radius and 4600 km long (versus 3.2 km radius and 32 km long in the Island Three design).[24]

Gallery

-

Bola space station

-

Bola Mars spacecraft

-

Kalpana One Orbital space station

-

Various Concepts

Current projects

The following projects and proposals, while not truly space habitats, incorporate aspects of what they would have and may represent stepping stones towards eventually building of space habitats.

The Nautilus-X Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle (MMSEV): this 2011 NASA proposal for a long-duration crewed space transport vehicle included an artificial gravity compartment intended to promote crew-health for a crew of up to six persons on missions of up to two years duration. The partial-g torus-ring centrifuge would utilize both standard metal-frame and inflatable spacecraft structures and would provide 0.11 to 0.69g if built with the 40 feet (12 m) diameter option.

The ISS Centrifuge Demo, also proposed in 2011 as a demonstration project preparatory to the final design of the larger torus centrifuge space habitat for the Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle. The structure would have an outside diameter of 30 feet (9.1 m) with a 30 inches (760 mm) ring interior cross-section diameter and would provide 0.08 to 0.51g partial gravity. This test and evaluation centrifuge would have the capability to become a Sleep Module for ISS crew.

The Bigelow Next-Generation Commercial Space Station was announced in mid-2010. The initial build-out of the station is expected in 2014/2015. Bigelow has publicly shown space station design configurations with up to nine modules containing 100,000 cu ft (2,800 m3) of habitable space. Bigelow began to publicly refer to the initial configuration as "Space Complex Alpha" in October 2010.

History

The idea of space habitats either in fact or fiction goes back to the latter 1800s. "The Brick Moon", a fictional story written in 1869 by Edward Everett Hale, is perhaps the first treatment of this idea in writing. In 1903, space pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky speculated about rotating cylindrical space colonies, with plants fed by the sun, in Beyond Planet Earth.[25][26] In the 1920s John Desmond Bernal and others speculated about giant space habitats. Dandridge M. Cole in the late 1950s and 1960s speculated about hollowing out asteroids and then rotating them to use as settlements in various magazine articles and books, notably Islands In Space: The Challenge Of The Planetoids.[22]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Space habitat. |

- Human outpost (artificially created controlled human habitat)

- Space colonization

- Space stations and habitats in fiction

- Spaceflight

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Doehring, James; et al. "Space Habitats". lifeboat.com. Lifeboat Foundation. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ↑ G. Kopp; J. Lean (2011). "A new, lower value of total solar irradiance: Evidence and climate significance". Geophys. Res. Lett.: L01706. Bibcode:2011GeoRL..3801706K. doi:10.1029/2010GL045777.

- ↑ "Echo". Encyclopedia Astronautica.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Pournelle, Jerrold E., Dr. (1980). A Step Farther Out. ISBN 0491029411.

- ↑ "Limits to Growth", Chapter 7, Space Settlements: A Design Study. NASA, 1975.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 O'Neill, Gerard K. (September 1974). "The Colonization of Space". Physics Today 27 (9): 32–40. Bibcode:1974PhT....27i..32O. doi:10.1063/1.3128863.

- ↑ Collins, Patrick et al. Artificial-Gravity Swimming-Pool. Space 98: Sixth International Conference and Exposition on Engineering, Construction, and Operations in Space. Albuquerque, New Mexico. April 26-30, 1998.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Globus, Al. "The Kalpana One Orbital Space Settlement Revised" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ↑ T. A. Heppenheimer. "Colonies in Space, Chapter 11: What's to Do on Saturday Night ?". Retrieved 1977. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Shepherd, L. R. (July 1952). "Interstellar Flight". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 11: 149–167.

- ↑ Gilster, Paul (28 February 2012). "Les Shepherd, RIP". centauri-dreams.org. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "Mass Shielding", Appendix E, Space Settlements: A Design Study. NASA (SP-413), 1975.

- ↑ Shepherd, Simon George. "Spacecraft Shielding". dartmouth.edu. Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth College. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ↑ Space Settlements: A Design Study, NASA, 1975

- ↑ Ames Summer Study on Space Settlements and Industrialization Using Nonterrestial Materials, NASA, 1977

- ↑ O'Neill, Gerard K., Dr. (1977). The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space. New York: William Morrow & Company.

- ↑ Heppenheimer, Fred, Dr. Habitats in Space.

- ↑ Globus, Al. "Lewis One Space Colony". Retrieved 2006-05-28.

- ↑ "The Kalpana One Orbital Space Settlement". National Space Society. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ↑ Bryan, Versteeg. "Kalpana One Animation Video". spacehabs.com. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Curreri, Peter A. A Minimized Technological Approach towards Human Self Sufficiency off Earth (PDF). Space Technology and Applications International Forum (STAIF) Conference. Albuquerque, NM. 11-15 February 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2010

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Bonnici, Alex Michael (8 August 2007). "Islands in Space: The Challenge of the Planetoids, the Pioneering Work of Dandridge M. Cole". Discovery Enterprise. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ Bishop, Forrest (1997). "Open Air Space Habitats". iase.cc. Institute of Atomic-Scale Engineering.

- ↑ McKendree, Thomas Lawrence. Implications of Molecular Nanotechnology Technical Performance Parameters on Previously Defined Space System Architectures. The Fourth Foresight Conference on Molecular Nanotechnology. Palo Alto, California, USA. 9-11 November 1995.

- ↑ K. Tsiolkovsky. Beyond Planet Earth Trans. by Kenneth Syers. Oxford, 1960.

- ↑ "Tsiolkovsky's Greenhouse". up-ship.com. 21 July 2010.

References

- NASA's table of contents for the studies See the "online books" about halfway down the page.

External links

- Lifeboat Foundation Space Habitats, a space habitat advocacy group.

- Paul Lucas (2005), Homesteading the High Frontier: The Shape of Space Stations to Come, Strange Horizons

- NPR visualization of a large-colony space habitat, May 2011.

- NASA video about space habitats and space settlements construction as seen around 1970"s (5 min)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||