Space Launch System

Artist's rendering of the SLS Block 1 launching with Orion. | |

| Function | Launch vehicle |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Project cost | US$7 billion (2014-2018, 2014 estimate),[1] to 35 billion (until 2025, 2011 estimate)[2][3] |

| Cost per launch | US$500 million (2012, planned)[4] to 5 billion[5][6] |

| Size | |

| Diameter | 27 ft 7 in (8.4 m) (core stage) |

| Stages | 2 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO |

150,000 to 290,000 lb (70,000 to 130,000 kg) |

| Associated rockets | |

| Family | Shuttle-Derived Launch Vehicles |

| Launch history | |

| Status | Undergoing development |

| Launch sites | LC-39B, Kennedy Space Center |

| First flight | No later than November 2018[7] |

| Notable payloads | Orion MPCV |

| Boosters (Block 1) | |

| No boosters | 2 Five-segment Solid Rocket Boosters |

| Thrust | 3,600,000 lbf (16,000 kN) |

| Total thrust | 7,200,000 lbf (32,000 kN) |

| Specific impulse | 269 seconds (2.64 km/s) (vacuum) |

| Burn time | 124 seconds |

| Fuel | PBAN, APCP |

| First Stage (Block 1, 1B, 2) - Core Stage | |

| Diameter | 27 ft 7 in (8.4 m) |

| Empty mass | 187,990 lb (85,270 kg) |

| Gross mass | 2,159,322 lb (979,452 kg) |

| Engines | 4 RS-25D/E[8] |

| Thrust | 1,670,000 lbf (7,440 kN) |

| Specific impulse | 363 seconds (3.56 km/s) (sea level), 452 seconds (4.43 km/s) (vacuum) |

| Fuel | LH2/LOX |

| Second Stage (Block 1) - ICPS | |

| Length | 44 ft 11 in (13.7 m) |

| Diameter | 16 ft 5 in (5 m) |

| Empty mass | 7,690 lb (3,490 kg) |

| Gross mass | 67,700 lb (30,710 kg) |

| Engines | 1 RL10B-2 |

| Thrust | 24,800 lbf (110.1 kN) |

| Specific impulse | 462 seconds (4.53 km/s) |

| Burn time | 1125 seconds |

| Fuel | LH2/LOX |

| Second Stage (Block 1B, Block 2) - Exploration Upper Stage | |

| Diameter | 27 ft 7 in (8.4 m) |

| Engines | 4 RL10 |

| Thrust | 99,000 lbf (440 kN) |

| Fuel | LH2/LOX |

The Space Launch System (SLS) is a United States Space Shuttle-derived heavy expendable launch vehicle being designed by NASA. It follows the cancellation of the Constellation program, and is to replace the retired Space Shuttle. The NASA Authorization Act of 2010 envisions the transformation of the Constellation program's Ares I and Ares V vehicle designs into a single launch vehicle usable for both crew and cargo.

The SLS launch vehicle is to be upgraded over time with more powerful versions. Its initial Block 1 version is to lift a payload of 70 metric tons to low Earth orbit (LEO), which will be increased with the debut of Block 1B and the Exploration Upper Stage.[9] Block 2 will replace the initial Shuttle-derived boosters with advanced boosters and is planned to have a LEO capability of more than 130 metric tons to meet the congressional requirement;[10] this would make the SLS the most capable heavy lift vehicle ever built.[11][12]

These upgrades will allow the SLS to lift astronauts and hardware to various beyond-LEO destinations: on a circumlunar trajectory as part of Exploration Mission 1 with Block 1, to a near-Earth asteroid in Exploration Mission 2 with Block 1B, and to Mars with Block 2. The SLS will launch the Orion Crew and Service Module and may support trips to the International Space Station if necessary. SLS will use the ground operations and launch facilities at NASA's Kennedy Space Center, Florida.

During the joint Senate-NASA presentation in September 2011, it was stated that the SLS program has a projected development cost of $18 billion through 2017, with $10 billion for the SLS rocket, $6 billion for the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle and $2 billion for upgrades to the launch pad and other facilities at Kennedy Space Center.[13][14]

Design and development

On September 14, 2011, NASA announced its design selection for the new launch system, declaring that it, in combination with the Orion spacecraft,[15] would take the agency's astronauts farther into space than ever before and provide the cornerstone for future US human space exploration efforts.[16][17][18]

Three versions of the launch vehicle are planned: Block 1, Block 1B, and Block 2. Each will use the same core stage with four main engines, but Block 1B will feature a more powerful second stage called the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS), and Block 2 will combine the EUS with upgraded boosters. Block 1 has a baseline LEO payload capacity of 70 metric tons (77 short tons) and Block 1B has a baseline of 105 metric tons (116 short tons). The proposed Block 2 will have similar lift capacity and height to the original Saturn V.[19] It was reported in February 2015 that NASA evaluations showed "over performance" versus the baseline payload for Block 1 and Block 1B.[20]

During the development of the SLS a number of different configurations were considered, including a Block 0 with three main engines,[21] a Block 1A variant which would have upgraded the vehicle's boosters instead of its second stage,[21] and a Block 2 with five main engines and a different second stage, the Earth Departure Stage, with up to three J-2X engines.[22]

On July 31, 2013 the SLS passed the Preliminary Design Review (PDR). The review encompassed all aspects of the SLS' design, not only the rocket and boosters but also ground support and logistical arrangements.[23] On August 7, 2014 the SLS passed a milestone known as Key Decision Point C and entered full-scale development, with an estimated launch date of November 2018.[24]

Vehicle description

Core stage

The core stage will be 8.4 meters (28 ft) in diameter and utilize four RS-25 engines.[8][21] Initial flights will use modified RS-25D engines left over from the Space Shuttle program,[25] later flights are expected to switch to a cheaper version of the engine not intended for reuse.[26] The stage's structure will consist of a modified Space Shuttle External Tank with the aft section adapted to accept the rocket's Main Propulsion System (MPS) and the top converted to host an interstage structure.[11][27] It will be fabricated at the Michoud Assembly Facility.[28]

The core stage will be common across all currently planned evolutions of the SLS. Initial planning included studies of a smaller Block 0 configuration with three RS-25 engines,[29][30] which was eliminated to avoid the need to substantially redesign the core stage for more powerful variants.[21] Likewise, while early Block 2 plans included five RS-25 engines on the core,[22] it was later baselined with four engines.[20]

Boosters

Shuttle-derived solid rocket boosters

Blocks 1 and 1B of the SLS will use two five-segment Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), which are based on the four-segment Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters. Modifications for the SLS included the addition of a center booster segment, new avionics, and new insulation which eliminates the Shuttle SRB's asbestos and is 860 kg (1,900 lb) lighter. The five-segment SRBs provide approximately 25% more total impulse than the Shuttle SRB and will not be recovered after use.[31][32]

Orbital ATK (formerly Alliant Techsystems) has completed four full-scale, full-duration static fire tests of the five-segment SRB. Development Motor 1 (DM-1) was tested on September 10, 2009; DM-2 was tested on August 31, 2010, and DM-3 on September 8, 2011. The DM-2 motor was cooled to a core temperature of 40 °F (4 °C), and DM-3 was heated to above 90 °F (32 °C). These tests validated motor performance at extreme temperatures.[33][34][35] Qualification Motor 1 (QM-1) was tested on March 10, 2015.[36]

Advanced boosters

For Block 2, NASA plans to switch from Shuttle-derived five-segment SRBs to advanced boosters.[37] This will occur after development of the Exploration Upper Stage for Block 1B. Early plans would have developed advanced boosters before an updated second stage; this configuration was called Block 1A. By 2012 NASA planned to select these new boosters through an Advanced Booster Competition which was to be held in 2015.[8][38] Several companies proposed boosters for this competition:

- Aerojet, in partnership with Teledyne Brown, offered a booster powered by three AJ1E6 engines, which would be a newly-developed LOX/RP-1 oxidizer-rich staged combustion engine. Each AJ1E6 engine would produce 4,900 kN (1,100,000 lbf) thrust using a single turbopump to supply dual combustion chambers.[39] On February 14, 2013, NASA awarded Aerojet a $23.3 million, 30-month contract to build a 2,400 kN (550,000 lbf) main injector and thrust chamber.[40]

- ATK proposed an advanced SRB nicknamed "Dark Knight". This booster would switch from a steel case to one made of lighter composite material, use a more energetic propellant, and reduce the number of segments from five to four.[41] It would deliver over 20,000 kN (4,500,000 lbf) maximum thrust and weigh 790,000 kg (1,750,000 lb) at ignition. According to ATK, the advanced booster would be 40% less expensive than the Shuttle-derived five-segment SRB. It is uncertain if the booster will allow SLS to deliver the mandated 130 t to LEO without the addition of a fifth engine to the core stage,[20] as a 2013 analysis indicated a maximum capacity of 113 t with the baselined four-engine core.[42]

- Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne and Dynetics proposed a liquid-fueled booster named "Pyrios".[43] The booster would use two F-1B engines which together would deliver a maximum of 16,000 kN (3,600,000 lbf) thrust and be able to continuously throttle to a minimum of 12,000 kN (2,600,000 lbf). The F-1B would be derived from the F-1 engine, which powered the first stage of the Saturn V. It would have been easier to assemble, with fewer parts and a simplified design,[44] while providing improved efficiency and a thrust increase of 110 kN (25,000 lbf).[45] Estimates in 2012 indicated that the Pyrios booster could increase Block 2 low Earth orbit payload to 150 t, 20 t more than the baseline.[41]

Christopher Crumbly, manager of NASA’s SLS advanced development office in January 2013 commented on the booster competition, "The F-1 has great advantages because it is a gas generator and has a very simple cycle. The oxygen-rich staged combustion cycle [Aerojet’s engine] has great advantages because it has a higher specific impulse. The Russians have been flying ox[ygen]-rich for a long time. Either one can work. The solids [of ATK] can work."[46]

Later analysis showed the Block 1A configuration would result in high acceleration which would be unsuitable for Orion and could require a costly redesign of the Block 1 core.[47] In 2014, NASA confirmed the development of Block 1B instead of Block 1A and called off the 2015 booster competition.[20][48] In February 2015 it was reported that SLS is expected to fly with the five-segment SRB until at least the late 2020s, and modifications to Launch Pad 39B, its flame trench, and SLS's Mobile Launcher Platform were evaluated based on SLS launching with solid-fuel boosters.[20]

Upper stage

Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage

Block 1, scheduled to fly Exploration Mission 1 (EM-1) by November 2018,[7] will use a the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS). This stage will be a modified Delta IV 5-meter Delta Cryogenic Second Stage (DCSS),[49] and will be powered by a single RL10B-2. Block 1 will be capable of lifting 70 t in this configuration, however the ICPS will be considered part of the payload and be placed into an initial 1,800 km by -93 km suborbital trajectory to ensure safe disposal of the core stage. ICPS will perform an orbital insertion burn at apogee, and then a translunar injection burn to send the uncrewed Orion on a circumlunar excursion.[50]

Exploration Upper Stage

The Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) is scheduled to debut on Exploration Mission 2 (EM-2). It is expected to be used by Block 1B and Block 2 and, like the core stage, will be 8.4 meters in diameter. The EUS would be powered by four RL10 engines,[51] and would complete the SLS ascent phase and then re-ignite to send its payload to destinations beyond low Earth orbit, similar to the role performed by the Saturn V's 3rd stage, the J-2 powered S-IVB.[52]

Other upper stages

- The Earth Departure Stage, powered by J-2X engines,[53][54] was to be the upper stage of the Block 2 SLS had NASA decided to develop Block 1A instead of Block 1B and the EUS.[52]

- An additional beyond LEO engine for interplanetary travel from Earth orbit to Mars orbit, and back, is being studied as of 2013 at Marshall Space Flight Center with a focus on nuclear thermal rocket (NTR) engines.[55] In historical ground testing, NTRs proved to be at least twice as efficient as the most advanced chemical engines, allowing quicker transfer time and increased cargo capacity. The shorter flight duration, estimated at 3–4 months with NTR engines,[56] compared to 8–9 months using chemical engines,[57] would reduce crew exposure to potentially harmful and difficult to shield cosmic rays.[58][59][60][61] NTR engines, such as the Pewee of Project Rover, were selected in the Mars Design Reference Architecture (DRA).[59][62][63][64]

- In 2013, NASA and Boeing analyzed the performance of several second stage options. The analysis was based on a second stage usable propellant load of 105 metric tons, except for the Block 1 and ICPS, which will carry 27.1 metric tons. These options are the following:[65]

- Without an upper stage, the SLS would be capable of delivering 70 t to low Earth orbit (LEO), and, using the ICPS, 20.2 t to Trans-Mars injection (TMI) and 2.9 t to Europa.

- A 4 engine RL10 upper stage could deliver 93.1 t to LEO, 31.7 t to TMI and 8.1 t to Europa.

- A 2 engine MB60 (an engine comparable to the RL60)[66] upper stage could deliver 97 t to LEO, 32.6 t to TMI and 8.5 t to Europa.

- A single engine J-2X upper stage, with higher thrust than other options, could deliver 105.2 t to LEO, but the lower specific impulse of the J-2X would decrease its beyond-LEO capability to 31.6 t to TMI and 7.1 to Europa.

Robotic exploration missions to Jupiter's water-ice moon Europa are increasingly seen as well suited to the lift capabilities of the Block 1B SLS.[67]

Fabrication

In mid-November 2014, construction of the first SLS began using the new welding system at NASA's Michoud Assembly Facility, where major rocket parts will be assembled.[68]

The SLS will have the ability to tolerate a minimum of 13 tanking cycles due to launch scrubs and other launch delays before launch. The assembled rocket is to be able to remain at the launch pad for a minimum of 180 days and can remain in stacked configuration for at least 200 days without destacking.[69]

In January 2015, NASA began test firing RS-25 engines in preparation for use on SLS.[26]

Program costs

In August 2014, as the SLS program passed its Key Decision Point C review and entered full development, costs from February 2014 until its planned launch in September 2018 were estimated at $7.021 billion.[24] Ground systems modifications and construction would require an additional $1.8 billion over the same time period. As of February 2015 the Orion spacecraft was expected to enter its Key Decision Point C review in the first half of 2015.[70]

During the joint Senate-NASA presentation in September 2011, it was stated that the SLS program had a projected development cost of $18 billion through 2017, with $10 billion for the SLS rocket, $6 billion for the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle and $2 billion for upgrades to the launch pad and other facilities at Kennedy Space Center.[13] These costs and schedule were considered optimistic in an independent 2011 cost assessment report by Booz Allen Hamilton for NASA.[71] An unofficial 2011 NASA document estimated the cost of the program through 2025 to total at least $41bn for four 70 t launches (1 unmanned, 3 manned),[2][3] with the 130 t version ready no earlier than 2030.[72]

The Human Exploration Framework Team (HEFT) estimated unit costs for Block 0 at $1.6bn and Block 1 at $1.86bn in 2010.[73] However, since these estimates were made the Block 0 SLS vehicle was dropped in late 2011, and the design was not completed;[74] NASA announced in 2013 that the European Space Agency will build the Orion Service Module.[75]

NASA SLS deputy project manager Jody Singer at Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama stated in September 2012 that $500 million per launch is a reasonable target cost for SLS, with a relatively minor dependence of costs on launch capability.[4] By comparison, the cost for a Saturn V launch was US$185 million in 1969 dollars,[76] which is roughly US$1.2 billion in 2014 dollars.

On July 24, 2014, Government Accountability Office audit predicted that SLS will not launch by the end of 2017 as originally planned since NASA is not receiving sufficient funding.[77]

Alternatives

The Space Access Society, Space Frontier Foundation and the Planetary Society called for cancellation of the project, arguing that SLS will consume the funds for other projects from the NASA budget and will not reduce launch costs;[78][79][80] some estimate this cost for the SLS to be about $8,500 per pound lifted to low earth orbit (LEO).[81] U.S. Representative Dana Rohrabacher and others added that instead, a propellant depot should be developed and the Commercial Crew Development program accelerated.[78][82][83][84][85] Two studies, one not publicly released from NASA[86][87] and another from the Georgia Institute of Technology, show this option to be a possibly cheaper alternative.[88][89]

Others suggest it will cost less to use an existing lower payload capacity rocket (Atlas V, Delta IV, Falcon 9, or the derivative Falcon Heavy), with on-orbit assembly and propellant depots as needed, rather than develop a new launch vehicle for space exploration without competition for the whole design.[90][91][92][93][94] The Augustine commission proposed an option for a commercial 75 metric ton launcher with lower operating costs, and noted that a 40 to 60 t launcher can support lunar exploration.[95]

Mars Society founder Robert Zubrin, who co-authored the Mars Direct concept, suggested that a heavy lift vehicle should be developed for $5 billion on fixed-price requests for proposal. Zubrin also disagrees with those that say the U.S. does not need a heavy-lift vehicle.[96] Based upon extrapolations of increased payload lift capabilities from past experience with SpaceX's Falcon launch vehicles, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk stated in 2010 that he would "personally guarantee" that his company could build the conceptual Falcon XX, a vehicle in the 140-150 t payload range, for $2.5 billion, or $300 million per launch, but cautioned that this price tag did not include a potential upper-stage upgrade.[97][98] SpaceX's privately-funded MCT launch vehicle, powered by nine Raptor engines, has also been proposed for lofting very large payloads from Earth in the 2020s.[99]

Rep. Tom McClintock and other groups argue that the Congressional mandates forcing NASA to use Space Shuttle components for SLS amounts to a de facto non-competitive, single source requirement assuring contracts to existing shuttle suppliers, and calling the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to investigate possible violations of the Competition in Contracting Act (CICA).[79][100][101] Opponents of the heavy launch vehicle have critically used the name "Senate launch system".[49] The Competitive Space Task Force, in September 2011, said that the new government launcher directly violates NASA’s charter, the Space Act, and the 1998 Commercial Space Act requirements for NASA to pursue the "fullest possible engagement of commercial providers" and to "seek and encourage, to the maximum extent possible, the fullest commercial use of space".[78]

Schedule

| Mission | Targeted date | Variant | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLS-1/EM-1 | By November 2018[7] | Block 1[22] | Send uncrewed Orion/MPCV on trip around the Moon. |

| SLS-2/EM-2 | c. 2025[102][103] | Block 1B[51] | Send the Orion (spacecraft) with four crew members to an asteroid that had been robotically captured and placed in lunar orbit two years in advance.[104] |

Proposed missions

Some of the currently proposed NASA Design Reference Missions (DRM) and others include:[22][63][105][106][107]

- ISS Back-Up Crew Delivery – a single launch mission of up to four astronauts via a Block 1 SLS/Orion-MPCV without an Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS) to the International Space Station (ISS) if the Commercial Crew Development program does not come to fruition. This potential mission mandated by the NASA Authorization Act of 2010 is deemed undesirable since the 70 t SLS and BEO Orion would be overpriced and overpowered for the mission requirements. Its current description is "delivers crew members and cargo to ISS if other vehicles are unable to perform that function. Mission length 216 mission days. 6 crewed days. Up to 210 days at the ISS."

- Tactical timeframe DRMs

- BEO Uncrewed Lunar Fly-by – Exploration Mission 1 (EM-1), a reclassification of SLS-1, is a single-launch mission of a Block 1 SLS with ICPS and a Block 1 Orion MPCV, with a destination of 70,000 km past the lunar surface.[108] Its current description is "Uncrewed Lunar Flyby: Uncrewed mission Beyond Earth Orbit (BEO) to test critical mission events and demonstrate performance in relevant environments. Expected drivers include: SLS and ICPS performance, MPCV environments, MPCV re-entry speed, and BEO operations."[105]

- BEO Crewed Lunar Orbit – Exploration Mission 2 (EM-2), is slated to be the first launch of a Block 1B SLS with the EUS and would send a crew on Orion to visit an asteroid placed in Lunar orbit. As of 2014, NASA was investigating options for instead launching a robotic spacecraft on this mission.[109]

- Strategic timeframe DRMs

- GEO mission – a dual-launch mission separated by 180 days to geostationary orbit. The first launch would comprise an SLS with a CPS and cargo hauler, the second an SLS with a CPS and Orion MPCV. Both launches would have a mass of about 110 t.

- A set of lunar missions enabled in the early 2020s ranging from Earth-Moon Lagrangian point-1 (EML-1) and low lunar orbit (LLO) to a lunar surface mission. These missions would lead to a lunar base combining commercial and international aspects.

- The first two missions would be single launches of SLS with a CPS and Orion MPCV to EML-1 or LLO and would have a mass of 90 t and 97.5 t respectively. The LLO mission is a crewed 12-day mission with three in lunar orbit. Its current description is "Low Lunar Orbit (LLO): Crewed mission to LLO. Expected drivers include: SLS and CPS performance, MPCV re-entry speed, and LLO environment for MPCV".

- The lunar surface mission set for the late 2020s would be a dual launch separated by 120 days. This would be a 19-day mission with seven days on the Moon's surface. The first launch would comprise an SLS with a CPS and lunar lander, the second an SLS with a CPS and Orion MPCV. Both would enter LLO for lunar-orbit rendezvous prior to landing at equatorial or polar sites on the Moon. Launches would have masses of about 130 t and 108 t, respectively. Its current description is "Lunar Surface Sortie (LSS): Lands four crew members on the surface of the Moon in the equatorial or polar regions and returns them to Earth," "Expected drivers include: MPCV operations in LLO environment, MPCV uncrewed ops phase, MPCV delta V requirements, RPOD (rendezvous, proximity operations and docking), MPCV number of habitable days.”

- Five Near Earth Asteroid (NEA) missions ranging from "minimum" to "full" capability are being studied. Among these are two NASA Near Earth Object (NEO) missions in 2026. A 155-day mission to NEO 1999 AO10, a 304-day mission to NEO 2001 GP2, a 490-day mission to a potentially hazardous asteroid such as 2000 SG344, utilizing two Block 1A/B SLS vehicles,[104] and a Boeing-proposed NEO mission to NEA 2008 EV5 in 2024. The latter would start from the proposed Earth-Moon L2 based Exploration Gateway Platform. Utilising an SLS third stage the trip would take about 100 days to arrive at the asteroid, 30 days for exploration, and a 235-day return trip to Earth.[112]

- Forward Work Martian Moon Phobos/Deimos, a crewed flexible path mission to one of the Martian moons. It would include 40 days in the vicinity of Mars and a return Venus flyby.

- Forward Work Mars Landing, a crewed mission, with four to six astronauts,[113] to a semi-permanent habitat for at least 540 days on the surface of the red planet in 2033 or 2045. The mission would include in-orbit assembly, with the launch of seven SLS Block 2 heavy-lift vehicles (HLVs) with a requirement of each being able to deliver 140 metric tons to low earth orbit (LEO). The seven HLV payloads, three of which would contain nuclear propulsion modules, would be assembled in LEO into three separate vehicles for the journey to Mars; one cargo In-Situ Resource Utilization Mars Lander Vehicle (MLV) created from two HLV payloads, one Habitat MLV created from two HLV payloads and a crewed Mars Transfer Vehicle (MTV), known as "Copernicus", assembled from three HLV payloads launched a number of months later. Nuclear Thermal Rocket engines such as the Pewee of Project Rover were selected in the Mars Design Reference Architecture (DRA) study as they met mission requirements being the preferred propulsion option because it is proven technology, has higher performance, lower launch mass, creates a versatile vehicle design, offers simple assembly, and has growth potential.[63][114]

- Other proposed missions

- 2024+ Single Shot MSR on SLS, a crewed flight with a telerobotic Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission proposed by NASA's Mars Program Planning Group. The time frame suggests SLS-5, a 105 t Block 1A rocket to deliver an Orion capsule, SEP robotic vehicle, and Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV). "Sample canister could be captured, inspected, encased and retrieved tele-robotically. Robot brings sample back and rendezvous with a crew vehicle." The mission may also include a "Possible Mars SEP (Solar Electric Power/Propulsion) Orbiter".[115]

- Potential sample return missions to Europa and Enceladus have also been noted.[116]

- Deep Space Habitat (DSH), NASA's planned usage of spare ISS hardware, experience, and modules for future missions to asteroids, Earth-Moon Lagrangian point and Mars.[117]

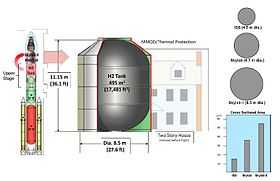

- Skylab II, proposal by Brand Griffin, an engineer with Gray Research Inc working with NASA Marshall, to use the upper stage hydrogen tank from SLS to build a 21st-century version of Skylab for future NASA missions to asteroids, Earth-Moon Lagrangian point-2 (EML2) and Mars.[118][119][120]

- SLS DoD Missions, the HLV will be made available for U.S. Department of Defense and other US government agencies to launch military or classified missions.

- Commercial payloads, such as the Bigelow Commercial Space Stations have also been referenced.

- Additionally "secondary payloads" mounted on SLS via an Encapsulated Secondary Payload Adapter (ESPA) ring could also be launched in conjunction with a "primary passenger" to maximize payloads.

- Monolithic telescope mission, SLS has been proposed by Boeing as a launch vehicle for the Advanced Technology Large-Aperture Space Telescope (ATLAST). This could be an 8 m monolithic telescope or a 16 m deployable telescope at Earth-Sun L2.[121]

- Solar probe mission, SLS has been proposed by Boeing as a launch vehicle for Solar Probe 2. This probe would be placed in a low perihelion orbit to investigate corona heating and solar wind acceleration to provide forecasting of solar radiation events.[121]

- Uranus mission, SLS has been proposed by Boeing as a launch vehicle for a Uranian probe. The rocket would "Deliver a small payload into orbit around Uranus and a shallow probe into the planet’s atmosphere." The mission would study the Uranian atmosphere, magnetic and thermal characteristics, gravitational harmonics as well as do flybys of Uranian moons.[121]

Funding

In Fiscal Year 2015, NASA received an appropriation of US$1.7 billion from Congress for SLS, an amount that was approximately US$320 million greater than the amount requested by the Obama administration.[122]

See also

- Ares V - cargo vehicle design for the Constellation Program of the 2000s.

- Comparison of orbital launchers families

- Comparison of orbital launch systems

- DIRECT - Ares V competitor, but with smaller payload capacity, based on Jupiter (rocket family).

- Energia - comparable vehicle to SLS Block 1 for Low Earth Orbit excursions.

- Exploration of Mars

- Human mission to Mars

- Morpheus Lander - rocket powered lander designed to use propellants manufactured on Mars.

- Nautilus-X - proposed deep space habitat module.

- Saturn MLV - modified super heavy lift Saturn V of 1960s, designed for Mars missions by 1980s.

- Saturn V ELV - enlarged Saturn V design concept of 1960s, with strapon Titan IV solid rocket boosters.

- Saturn V-3 - upgraded Saturn V design concept of 1960s, using F-1A 1st stage engines & HG-3 2nd stage engines.

- Shuttle-Derived Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle - concept vehicle with a lower lift capability than Saturn V.

- Magnum (rocket) - a 1990s concept with a similar lift capability to Block 1 and Block 1B but lower than the Saturn V.

- Space exploration technologies

- Space Exploration Vehicle

- Space policy of the Barack Obama administration

- Space Shuttle successors

Videos

-

Space Launch System Booster Passes Major Ground Test

-

Igniting the Booster Space Launch System

References

- ↑ "NASA commits to $7 billion mega rocket, 2018 debut". CBS News. August 27, 2014. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 ANDY PASZTOR (September 7, 2011). "White House Experiences Sticker Shock Over NASA's Plans". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "ESD Integration, Budget Availability Scenarios" (PDF). Space Policy Online. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "NASA's huge new rocket may cost $500 million per launch". MSNBC. September 12, 2012.

- ↑ Lee Roop (July 29, 2013). "NASA defends Space Launch System against charge it 'is draining the lifeblood' of space program". Alabama local news. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ John Strickland (July 15, 2013). "Revisiting SLS/Orion launch costs". The Space Review. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 http://www.nasa.gov/press/2014/august/nasa-completes-key-review-of-world-s-most-powerful-rocket-in-support-of-journey-to/#.U_5UAfl7Eeg

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "NASA space launch system" (PDF). c. 2012.

- ↑ "Space Launch System". aerospaceguide.net.

- ↑ "The NASA Authorization Act of 2010". Featured Legislation. Washington DC, USA: United States Senate. July 15, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Stephen Clark (March 31, 2011). "NASA to set exploration architecture this summer". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ Dwayne Day (November 25, 2013). "Burning thunder".

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Marcia Smith (14 September 2011). "New NASA Crew Transportation System to Cost $18 Billion Through 2017". Space Policy Online. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ Bill Nelson, Kay Bailey Hutchison, Charles F. Bolden (September 14, 2011). Future of NASA Space Program. Washington, D.C.: Cspan.org.

- ↑ "NASA Announces Key Decision For Next Deep Space Transportation System". NASA. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ "NASA Announces Design For New Deep Space Exploration System". NASA. 14 September 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ "Press Conference on the Future of NASA Space Program". C-Span. 14 September 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ Kenneth Chang (September 14, 2011). "NASA Unveils New Rocket Design". New York Times. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ Karl Tate (16 September 2011). "Space Launch System: NASA's Giant Rocket Explained". Space.com. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Bergin, Chris. "Advanced Boosters progress towards a solid future for SLS". NasaSpaceFlight.com. Retrieved February 2015.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Chris Bergin (4 October 2011). "SLS trades lean towards opening with four RS-25s on the core stage". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 "Acronyms to Ascent – SLS managers create development milestone roadmap". NASASpaceFlight.com. 23 February 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ "NASA's Space Launch System Program PDR: Answers to the Acronym". NASA. 1 August 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Foust, Jeff (August 27, 2014). "SLS Debut Likely To Slip to 2018". SpaceNews.com. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- ↑ Sloss, Philip. "NASA ready to power up the RS-25 engines for SLS". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Bergin, Chris. "Stennis conducts SLS engine firing marking RS-25 return". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved January 2015.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (14 September 2011). "SLS finally announced by NASA – Forward path taking shape". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ "NASA's Space Launch System Core Stage Passes Major Milestone, Ready to Start Construction". Space Travel. 27 December 2012.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (April 25, 2011). "SLS planning focuses on dual phase approach opening with SD HLV". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (June 16, 2011). "Managers SLS announcement after SD HLV victory". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ↑ Priskos, Alex. "Five-segment Solid Rocket Motor Development Status" (PDF). ntrs.nasa.gov. NASA. Retrieved 2015-03-11.

- ↑ "Space Launch System: How to launch NASA’s new monster rocket". NASASpaceFlight.com. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ "NASA and ATK Successfully Test Ares First Stage Motor". NASA. 10 September 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ↑ "NASA and ATK Successfully Test Five-Segment Solid Rocket Motor". NASA. 31 August 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ↑ NASA Successfully Tests Five-Segment Solid Rocket Motor, NASA, 31 August 2010, retrieved 8 September 2011

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (March 10, 2015). "QM-1 shakes Utah with two minutes of thunder". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ Keith Cowing (September 14, 2011). "NASA's New Space Launch System Announced – Destination TBD". SpaceRef. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ↑ Frank Morring (17 June 2011). "NASA Will Compete Space Launch System Boosters". Aviation Week. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ↑ "NASA’s Space Launch System: Partnering For Tomorrow" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Rachel Kraft (February 14, 2013). "NASA Awards Final Space Launch System Advanced Booster Contract". NASA. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "The Dark Knights – ATK’s Advanced Boosters for SLS revealed". 2013-01-14.

- ↑ "Table 2. ATK Advanced Booster Satisfies NASA Exploration Lift Requirements".

- ↑ Lee Hutchinson (2013-04-15). "New F-1B rocket engine upgrades Apollo-era design with 1.8M lbs of thrust". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ↑ "Dynetics reporting "outstanding" progress on F-1B rocket engine". Ars Technica. 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ↑ Lee Hutchinson (2013-04-15). "New F-1B rocket engine upgrades Apollo-era design with 1.8M lbs of thrust". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ↑ "SLS Block II drives hydrocarbon engine research". thespacereview.com. January 14, 2013.

- ↑ http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/07/wind-tunnel-testing-sls-configurations-block-1b/

- ↑ "News from the 30th Space Symposium | Second SLS Mission Might Not Carry Crew". spacenews.com. May 21, 2014. Retrieved July 2014.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Rosenberg, Zach. "Delta second stage chosen as SLS interim". Flight International, May 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Space Launch System Data Sheet". SpaceLaunchReport.com. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "NASA confirms EUS for SLS Block 1B design and EM-2 flight". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "SLS prepares for PDR – Evolution eyes Dual-Use Upper Stage". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (November 9, 2011). "SLS J-2X Upper Stage engine enjoys successful 500 second test fire". nasaspaceflight.com.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (February 12, 2013). "Second J-2X engine prepares for SLS testing". nasaspaceflight.com.

- ↑ http://www.space-travel.com/reports/NASA_Researchers_Studying_Advanced_Nuclear_Rocket_Technologies_999.html

- ↑ "NUCLEAR ROCKETS: To Mars and Beyond Nuclear Rockets: Then and Now. LANL".

- ↑ "How long would a trip to Mars take?".

- ↑ "How Fast Could (Should) We Go to Mars? Comparing Nuclear Electric Propulsion (NEP) with the Nuclear Thermal Rocket (NTR) and Chemical Rocket for Sustainable 1-year human Mars round-trip mission".

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "A One-year Round Trip Crewed Mission to Mars using Bimodal Nuclear Thermal and Electric Propulsion (BNTEP) (doi: 10.2514/6.2013-4076)".

- ↑ Borowski, Stanley K.; McCurdy, David R.; Packard, Thomas W. (April 9, 2012). "Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP): A Proven Growth Technology for Human NEO / Mars Exploration Missions" (PDF). NASA.

- ↑ Borowski, Stanley K.; McCurdy, David R.; Packard, Thomas W. (August 16, 2012). "Nuclear Thermal Rocket/Vehicle Characteristics And Sensitivity Trades For NASA's Mars Design Reference Architecture (DRA) 5.0 Study" (PDF). NASA.

- ↑ "Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP): A Proven Growth Technology for Human NEO / Mars Exploration Missions" (PDF). 2012.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 "SLS Exploration Roadmap evaluations provide clues for human Mars missions January 24, 2012 by Chris Bergin".

- ↑ "NASA Researchers Studying Advanced Nuclear Rocket Technologies by Rick Smith for Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville AL (SPX) Jan 10, 2013".

- ↑ Chris Gebhardt (November 13, 2013). "SLS upper stage proposals reveal increasing payload-to-destination options". nasaspaceflight.com.

- ↑ "Program Status of the Pratt & Whitney RL60 Engine" (PDF).

- ↑ "A generational opportunity for Europa, by Casey Dreier, Monday, July 21, 2014".

- ↑ SLS Engine Section Barrel Hot off the Vertical Weld Center at Michoud. NASA

- ↑ "SLS to be robust in the face of scrubs, launch delays and pad stays". NASASpaceFlight.com. 4 April 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Davis, Jason. "NASA Budget Lists Timelines, Costs and Risks for First SLS Flight". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2015-03-11.

- ↑ "Independent Cost Assessment of the Space Launch System, Multi-purpose Crew Vehicle and 21st Century Ground Systems Programs: Executive Summary of Final Report" (PDF). Booz Allen Hamilton. NASA.gov. 19 August 2011.

- ↑ Marcia Smith (9 September 2011). "The NASA Numbers Behind That WSJ Article". Space Policy Online. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "HEFT Phase I Closeout" (PDF). nasawatch.com. September 2010. p. 69.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (4 October 2011). "SLS trades lean towards opening with four RS-25s on the core stage". NASA Spaceflight.com. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ↑ NASA Signs Agreement for a European-Provided Orion Service Module

- ↑ "SP-4221 The Space Shuttle Decision- Chapter 6: ECONOMICS AND THE SHUTTLE". NASA. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ↑ Morrison, Lauren; Bale, Lauren (July 24, 2014). "Federal audit reveals not enough money for NASA to get SLS off the ground". 48 WAFF.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 Henry Vanderbilt (15 September 2011). "Impossibly High NASA Development Costs Are Heart of the Matter". moonandback.com. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Ferris Valyn (15 September 2011). "Monster Rocket Will Eat America’s Space Program". Space Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ "Statement before the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology US House of Representatives Hearing: A Review of the NASA's Space Launch System" (PDF). The Planetary Society. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ "The SLS: too expensive for exploration?". thespacereview.com. 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Rohrabacher, Dana (14 September 2011). "Nothing New or Innovative, Including It's Astronomical Price Tag". Retrieved 14 Sep 2011.

- ↑ "Rohrabacher calls for "emergency" funding for CCDev". parabolicarc.com. 24 August 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ Jeff Foust (15 September 2011). "A monster rocket, or just a monster?". The Space Review.

- ↑ Jeff Foust (1 November 2011). "Can NASA develop a heavy-lift rocket?". The Space Review.

- ↑ Mohney, Doug (21 October 2011). "Did NASA Hide In-space Fuel Depots To Get a Heavy Lift Rocket?". Satellite Spotlight. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ "Propellant Depot Requirements Study" (PDF). HAT Technical Interchange Meeting. 21 July 2011.

- ↑ Cowing, Keith (12 October 2011). "Internal NASA Studies Show Cheaper and Faster Alternatives to the Space Launch System". SpaceRef.com. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ "Near Term Space Exploration with Commercial Launch Vehicles Plus Propellant Depot" (PDF). Georgia Institute of Technology / National Institute of Aerospace. 2011.

- ↑ "Affordable Exploration Architecture" (PDF). United Launch Alliance. 2009.

- ↑ Grant Bonin (6 June 2011). "Human spaceflight for less: the case for smaller launch vehicles, revisited". The Space Review.

- ↑ Robert Zubrin (14 May 2011). "How We Can Fly to Mars in This Decade—And on the Cheap". Mars Society.

- ↑ Rick Tumlinson (15 September 2011). "The Senate Launch System – Destiny, Decision, and Disaster". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Andrew Gasser (24 October 2011). "Propellant depots: the fiscally responsible and feasible alternative to SLS". The Space Review.

- ↑ Review of U.S. Human Space Flight Plans Committee; Augustine, Austin, Chyba, Kennel, Bejmuk, Crawley, Lyles, Chiao, Greason, Ride (October 2009). "Seeking A Human Spaceflight Program Worthy of A Great Nation" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ↑ Alan Boyle (7 December 2011). "Is the case for Mars facing a crisis?". MSNBC.

- ↑ John K. Strickland, Jr. "The SpaceX Falcon Heavy Booster: Why Is It Important?". National Space Society. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "NASA Studies Scaled-Up Falcon, Merlin". Aviation Week. 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (August 29, 2014). "Battle of the Heavyweight Rockets -- SLS could face Exploration Class rival". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved 2014-08-30.

- ↑ "Congressman, Space Frontier Foundation, And Tea Party In Space Call For NASA SLS Investigation". moonandback.com. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ "The Senate Launch System". Competitive Space. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ "Orion's First Test Flight Offers Space Launch System a First Look at Hardware Operation, Integration". NASA. June 29, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ↑ "NASA Announces Next Steps on Journey to Mars: Progress on Asteroid Initiative". NASA. March 25, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 "NASA managers evaluate yearlong deep space asteroid mission September 9, 2013 by Marshall Murphy".

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Chris Bergin (15 December 2011). "Building the Roadmap for SLS – Con Ops lays out the LEO/Lunar Options". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ "SLS interest in DoD launch market and Secondary Payloads potential". NASASpaceFlight.com. 4 February 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ "NASA Exploration Roadmap: A return to the Moon’s surface documented". NASASpaceFlight.com. 19 March 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (July 2, 2013). "EM-1: NASA managers request ambitious changes to debut SLS/Orion mission". nasaspaceflight.com.

- ↑ "Orion’s crewed asteroid mission unlikely to occur prior to 2024". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ↑ "SMALL PRESSURIZED ROBOT (CHARIOT WITH A CABIN)".

- ↑ "Human Exploration of Mars Design Reference Architecture 5.0 2009." (PDF).

- ↑ http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/11/long-duration-iss-crew-foundations-beo-missions/

- ↑ Chris Bergin (October 6, 2013). "NASA Con Ops Assess Baseline Features for SLS/Orion Mission to Mars".

- ↑ "Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP): A Proven Growth Technology for Human NEO / Mars Exploration Missions" (PDF).

- ↑ Chris Bergin (30 November 2012). "NASA interest in 2024 Mars Sample Return Mission using SLS and Orion". NASASpaceFlight.com.

- ↑ http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/11/nasa-payload-fairings-options-multi-mission-sls-capability/

- ↑ NASA's Deep Space Habitat

- ↑ Markus Hammonds (14 April 2013). "Skylab II:Living Beyong the Dark Side of the Moon". Discovery.

- ↑ http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/03/dsh-module-concepts-outlined-beo-exploration/

- ↑ Frank Morring, Jr. (22 October 2012). "NASA Deep-Space Program Gaining Focus". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 121.2 Chris Gebhardt (20 November 2013). "New SLS mission options explored via new Large Upper Stage". NASASpaceFlight.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (2014-12-14). "NASA gets budget hike in spending bill passed by Congress". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Space Launch System. |

- Space Launch System & Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle page on NASA.gov

- "Preliminary Report on Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle and Space Launch System" (PDF), NASA.

- SLS Future Frontiers video

- Video animations of mission to asteroid, moon and mars

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||