Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Moldova |

|

| Antiquity |

| Early Middle Ages |

| Principality of Moldavia |

|

| Bessarabia Governorate |

| Moldavian Democratic Republic |

| Greater Romania |

|

| Moldavian ASSR |

| Moldavian SSR |

| Republic of Moldova |

|

| Moldova portal |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Romania |

|

|

Post-Revolution |

|

| Romania portal |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Ukraine |

|

|

Prehistory |

|

Modern history

|

|

Topics by history |

| Ukraine portal |

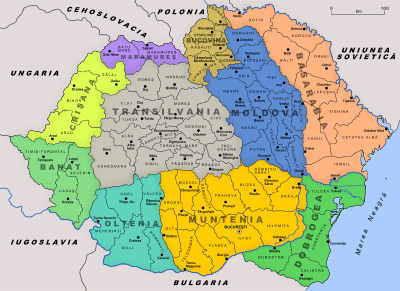

The Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina was the military occupation of the formerly Romanian regions of Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and Hertza by the Soviet Red Army during June 28 – July 4, 1940. These regions, with a total area of 50,762 km2 (19,599 sq mi) and a population of 3,776,309 inhabitants, were subsequently incorporated into the USSR.[1][2]

The Soviet Union had planned to accomplish the annexation with a full-scale invasion, but the Romanian government, responding to a Soviet ultimatum delivered on June 26, agreed to withdraw from the territories in order to avoid a military conflict. Germany, which had acknowledged the Soviet interest in Bessarabia in a secret protocol to the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, had been made aware prior to the planned ultimatum on June 24, but had not informed the Romanian authorities, nor were they willing to provide support.[3] The fall of France, a guarantor of Romania's borders, on 22 June, is considered an important factor in the Soviet decision to issue the ultimatum.[4]

On August 2, 1940, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed as a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, encompassing most of Bessarabia, as well as a portion of the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, an autonomous republic of the Ukrainian SSR located on the left bank of the Dniester (nowadays, the breakaway Transnistrian state). The Hertza region, and the regions inhabited by Slavic majorities (Northern Bukovina, Northern and Southern Bessarabia) were included in the Ukrainian SSR. The Soviet administration was marked by a series of campaigns of political persecution, including arrests, deportations to labour camps, and executions.

In July 1941, Romanian and German troops recaptured Bessarabia during the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union. A military administration was established and the region's Jewish population was either executed on the spot or deported to Transnistria, where further numbers were killed. In August 1944, during the Soviet Jassy-Kishinev Offensive, the Axis war effort on the Eastern Front collapsed. A coup d'état in Romania on 23 August 1944 caused the Romanian army to cease resisting the Soviet advance and later join the fight against Germany. Soviet forces advanced from Bessarabia into Romania, capturing most of its standing army as POWs and occupying the country.[5] On September 12, 1944, Romania signed the Moscow Armistice with the Allies. The Armistice, as well as the subsequent peace treaty of 1947, confirmed the Soviet-Romanian border as it was on January 1, 1941.[6][7]

Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and Hertza remained part of the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991, when they became part of the newly independent states of Moldova and Ukraine. In its declaration of independence of August 27, 1991, the government of Moldova condemned the creation of the Moldavian SSR, declaring that it had no legal basis.[8]

Background

Soviet-Romanian relations during the interwar period

The Bessarabian question was both political and national in nature. According to the 1897 census, Bessarabia, at the time a guberniya of the Russian Empire, had a population that was 47.6% Moldovans, 19.6% Ukrainians, 8% Russians, 11.8% Jews, 5.3% Bulgarians, 3.1% Germans, and 2.9% Gagauz.[9][10] These figures showed a strong decrease in the proportion of Moldovans/Romanians in comparison to the census of 1817, conducted shortly after the Russian Empire annexed Bessarabia in 1812. According to the data of this census, Moldovans/Romanians represented 86% of the population.[11] The decrease seen in the census of 1897 was due to the settling by the Tsarist authorities of other nationalities in the territory of Bessarabia.[10]

During the 1917 Russian Revolution, a National Council was formed in Bessarabia to manage the province.[12] The council, known locally as Sfatul Țării, initiated several national and social reforms, and on December 2/15 1917 declared Bessarabia an autonomous republic within the Russian Federative Democratic Republic.[13][14] The Rumcherod, a rival council loyal to the Petrograd Soviet, was also formed and by late December had gained control over the capital, Chișinău, and proclaimed itself the sole authority over Bessarabia.[13][15] With the consent of the Entente, and, according to the Romanian historiography, on the request of Sfatul Țării, Romanian troops entered Bessarabia in early January, and by February had pushed the Soviets over the Dniester.[16][17] Despite later declarations by the Romanian prime minister that the military occupation was made with the consent of the Bessarabian government,[18] the intervention was met with protest by the locals, notably by Ion Inculeț, president of Sfatul Țării, and Pantelimon Erhan, head of the provisional Moldavian executive.[19] The executive even authorised the badly organised Moldavian militia to resist the Romanian advance, although with little success.[20] In the wake of the intervention, Soviet Russia broke off diplomatic relations with Romania and confiscated the Romanian Treasure, at the time stored in Moscow for safekeeping.[21] To calm the situation, the Entente representatives in Iași issued a guarantee that the presence of the Romanian Army was only a temporary military measure for the stabilisation of the front, without further effects on the political life of the region.[17] In January 1918, Ukraine declared its independence from Russia, leaving Bessarabia physically isolated from the Petrograd government, and leading to the declaration of independence of the Moldavian Republic on January 24/February 5.[21] Some historians consider that the declaration was made under Romanian pressure.[16] Following several Soviet protests, on February 20/March 5, the Romanian prime minister, General Alexandru Averescu, signed a treaty with the Soviet representative in Odessa, Christian Rakovsky, which provided that Romanian troops be evacuated from Bessarabia in the following two months in exchange for the repatriation of Romanian POWs held by the Rumcherod.[22] After the White Army forced the Soviets to withdraw from Odessa, and the German Empire agreed to the Romanian annexation of Bessarabia in a secret agreement (part of the Buftea Peace Treaty) on March 5/18,[16][23] Romanian diplomacy repudiated the treaty, claiming the Soviets were unable to fulfil their obligations.[17]

On March 27/April 9, 1918, Sfatul Țării voted for the union of Bessarabia with Romania, conditional upon the fulfilment of an agrarian reform. There were 86 votes for union, 3 votes against union, 36 deputies refrained from voting, and 13 deputies were absent from this session. The vote is regarded as controversial by several historians, including Romanian ones such as Cristina Petrescu and Sorin Alexandrescu.[24] According to United States historian Charles King, with Romanian troops already in Chișinău, Romanian planes circling above the meeting hall, and the Romanian prime minister waiting in the foyer, many minority deputies chose simply not to vote.[25] On April 18 Georgy Chicherin, the Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs, sent a note of protest against the incorporation of Bessarabia into Romania.[26]

In August 1916, the Entente and neutral Romania signed a secret Convention that stipulated Romania would join the war against the Central Powers in exchange for several territories of Austria-Hungary, among them, Bukovina.[27] During the last part of World War I, national movements of the Romanians and the Ukrainians began to emerge in the province; however, the two movements had conflicting aims, each seeking to unite the province with their national state.[28] Thus, on October 25, 1918, a Ukrainian National Committee, gaining the upper hand in Czernowitz, declared Northern Bukovina, populated by a Ukrainian majority, part of the West Ukrainian People's Republic.[29] On October 27, the Romanians followed suit, proclaiming the whole region united with Romania,[30] and calling in Romanian troops.[16] The Romanian intervention quickly established the Romanian Assembly as the dominant force, and on November 28 a Congress of the Romanians, Germans, and Poles voted to unite with Romania. The representatives of the Ukrainian and Jewish populations boycotted the Congress, and the struggle between ethnic factions continued for several months.[29]

During the Russian civil war, the Soviet governments of Ukraine and Russia, prompted by the unrest in Bessarabia due to Romanian occupation, issued a joint ultimatum to Romania on May 1, 1919, demanding its withdrawal from Bessarabia, and the next day, Christian Rakovsky, the Chairman of the Ukrainian Soviet government, issued another ultimatum demanding the withdrawal of Romanian troops from Bukovina as well. The Red Army pushed the Romanians over the Dniester, and a Besarabian Soviet Republic was proclaimed. The ultimatum also came in the context of the Hungarian Revolution, with the Soviets hoping to prevent a Romanian intervention in Hungary. A large-scale rebellion in Ukraine prevented further Soviet advances.[16][31][32] Soviet Russia would continue its policy of non-recognition of Romanian sovereignty over Bessarabia, which it considered Romanian-occupied territory, until the 1940 events.

During the negotiations pre-dating the Treaty of Paris, the United States representative asked for a plebiscite to be held in Bessarabia to decide its future; however, the proposal was rejected by the head of the Romanian delegation, Ion I. C. Brătianu, who claimed such an undertaking would allow the distribution of Bolshevik propaganda in Bessarabia and Romania.[33] A plebiscite was also requested at the Peace Conference by the White Russians, only to be rejected again.[34] The Soviets would continue to press for a plebiscite during the following decade, only to be dismissed every time by the Romanian government.[35]

Romanian sovereignty over Bessarabia was de jure recognized by the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Japan in the Bessarabian Treaty signed on October 28, 1920. Soviet Russia and Ukraine promptly notified Romania that they did not recognize the treaty's validity, and did not consider themselves bound by it.[36] Ultimately, Japan failed to ratify the treaty, and thus it never came into force,[37] leaving Romania without a valid international act to justify its possession of Bessarabia.[38] The United States refused to discuss territorial changes in the former Russian Empire without the participation of a Russian government.[39] Thus, it declined to recognize the incorporation of Bessarabia into Romania, and, unlike its position of recognizing the independence of the Baltic States, it insisted that Bessarabia was a territory under Romanian military occupation, and incorporated the Bessarabian emigration quota into the Russian one in 1923.[40] In 1933, the U.S. government tacitly included the Bessarabian emigration quota into that of Romania, an act considered a de facto recognition by Romanian diplomacy.[41] However, during World War II, the U.S. argued it had never recognized Bessarabia's union with Romania.[42]

In 1924, after the failure of the Tatarbunar Uprising, the Soviet government created a Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic on the left bank of the Dniester river within the Ukrainian SSR. The Romanian government saw this as a threat and a possible staging ground for a Communist invasion of Romania. Throughout the 1920s, Romania considered itself a pillar in the cordon sanitaire policy of containment of the Bolshevik threat, and avoided direct relations with the Soviet Union.

On August 27, 1928, both Romania and the Soviet Union signed and ratified the Kellogg-Briand Pact, renouncing war as an instrument of national policy.[43] Following this, on February 9, 1929, the Soviet Union signed a protocol with its western neighbors, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, and Romania, confirming adherence to the terms of the Pact.[44] In signing the Pact, the contracting parties agreed to condemn war as a recourse to solving conflict, to renounce it as an instrument of policy, and that all conflicts and disputes were to be settled only by peaceful means.[45] At this time, the Soviet ambassador, Maxim Litvinov, made it clear that neither the pact nor the protocol meant renunciation of Soviet rights over the "territories occupied by Romanians".[46] On July 3, 1933, amongst others, Romania and the Soviet Union signed the London Convention for the Definition of Aggression, Article II of which defined several forms of aggression: "There shall be recognized as an aggressor that State which shall be the first to have committed one of the following actions: First—a declaration of war on another State. Second—invasion by armed forces of the territory of another State even without a declaration of war. (...)" and "No political, military, economic or other considerations may serve as an excuse or justification for the aggression referred to in Article II."

In January 1932 in Riga, and in September 1932 in Geneva, Soviet-Romanian negotiations were held as a prelude to a non-aggression treaty, and on June 9, 1934, diplomatic relations were established between the two countries. On July 21, 1936, Maxim Litvinov and Nicolae Titulescu, the Soviet and Romanian Ministers of Foreign Affairs, agreed upon a draft of a Mutual Assistance Pact.[47] It was sometimes interpreted as a non-aggression treaty, that would de facto recognize the existing Soviet-Romanian border. The protocol stipulated that any common Romanian-Soviet action should be pre-approved by France. In negotiating with the Soviets for this agreement, Titulescu was highly criticized by the Romanian far right. The protocol was to be signed in September 1936. However, Titulescu was dismissed in August 1936, leading the Soviet side to declare the previously achieved agreement null and void. Subsequently, no further attempts were made to reach a political rapprochement between Romania and the Soviet Union.[48] Moreover, by 1937, Litvinov and the Soviet press revived the dormant claim over Bessarabia.[49]

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

On August 23, 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a non-aggression treaty that contained an additional secret protocol with maps, in which a demarcation line through Eastern Europe was drawn, dividing it into the German and Soviet interest zones. Bessarabia was among the regions assigned to the Soviet sphere of interest by the Pact. Article III of its Secret Additional Protocol states:

With regard to Southeastern Europe attention is called by the Soviet side to its interest in Bessarabia. The German side declares its complete political disinterestedness in these areas.[50]

International context at the beginning of World War II

Assured by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of Soviet non-interference, Germany started World War II one week later by invading Poland from the west on September 1, 1939. The Soviet Union attacked Poland from the east on September 17, and by September 28, Poland had fallen. Romanian Prime Minister Armand Călinescu, a strong supporter of Poland in its conflict with Germany, was assassinated on September 21 by elements of the Romanian far right with Nazi support. Romania remained formally neutral in the conflict, but aided Poland by providing access to Allied military supplies from the Black Sea to the Polish border, and also a route for the Polish government and army to withdraw after the defeat. The Polish government also preferred a formally neutral Romania because that ensured the safety from German bombardments of supplies transported through Romanian territory. (See also Romanian Bridgehead.)

On June 2, 1940, Germany informed the Romanian government that, in order to receive territorial guarantees, Romania should consider negotiations with the Soviet Union.

From June 14–17, 1940, the Soviet Union gave ultimatum notes to, Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia, and when these ultimata were satisfied, used bases thus gained to occupy these territories.

France's surrender on June 22 and the subsequent British retreat from Europe rendered their assurances of assistance to Romania meaningless.

Political and military developments

Soviet preparations

By directives OV/583 and OV/584 of the Soviet People Commissariat of Defense, military units of the Odessa Military District were ordered into battle-ready state in the spring of 1940. Soviet troops were concentrated along the Romanian border between April 15 and June 10, 1940. In order to coordinate the efforts of the Kiev and Odessa military districts in the preparation of action against Romania, the Soviet Army created the Southern Front under General Georgy Zhukov. This was composed of the 5th, 9th and 12th Armies. The Southern Front had 32 infantry divisions, 2 motorized infantry divisions, 6 cavalry divisions, 11 tank brigades, 3 paratrooper brigades, 30 artillery regiments, and smaller auxiliary units.[51]

Two action plans were devised. The first plan was prepared for the eventuality that Romania would not agree to evacuate Bessarabia and Bukovina. The Soviet 12th Army was to strike southward along the Prut river towards Iaşi, while the Soviet 9th Army was to strike westwards, south of Chişinău towards Huşi. The objective of this plan was to surround the Romanian troops in the Bălţi-Iaşi area. The second plan took into consideration the possibility that Romania would agree to Soviet demands and evacuate its military forces. In such a situation, Soviet troops were given the mission to quickly reach the Prut river and oversee the evacuation of Romanian troops. The first plan was taken as the default course of action. Along the portions of the border where the offensive was planned to take place, the Soviets prepared at least a triple superiority of men and materiel.[51]

Soviet ultimatum

On June 26, 1940, at 22:00, Soviet People's Commissar Vyacheslav Molotov presented an ultimatum note to Gheorghe Davidescu, Romanian ambassador to Moscow, in which the Soviet Union demanded the evacuation of the Romanian military and civil administration from Bessarabia and the northern part of Bukovina.[52] The Soviets stressed their sense of urgency: "Now that the military weakness of the USSR is a thing of past, and the international situation that was created requires the rapid solution of the items inherited from the past, in order to fix the basis of a solid peace between countries (...)".[53] The German Minister of Foreign Affairs, Joachim von Ribbentrop, was informed by the Soviets of their intentions to send an ultimatum to Romania regarding Bessarabia and Bukovina on June 24, 1940. In the ensuing diplomatic coordination, Ribbentrop mainly expressed concern for the fate of the ethnic Germans in these two provinces, claiming the number of Germans in Bessarabia to be 100,000, and affirmed that Soviet demands regarding Bukovina were new . He also pointed out that Germany had strong economic interests in the rest of the Romanian territory.[a]

The text of the ultimatum note sent to Romania on June 26, 1940, incorrectly stated that Bessarabia was populated mainly by Ukrainians: "[...] centuries-old union of Bessarabia, populated mainly by Ukrainians, with the Ukrainian Soviet Republic". The Soviet government demanded the northern part of Bukovina as a "minor reparation for the enormous loss inflicted on the Soviet Union and Bessarabia's population by 22 years of Romanian reign over Bessarabia", and because its "[...] fate is linked mainly with the Soviet Ukraine by the community of its historical fate, and by the community of language and ethnic composition". Northern Bukovina had some historical connections with Galicia, annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939 as part of its invasion of Poland, in the sense that both had previously been part of Austria-Hungary from the second part of the 18th century until 1918. Northern Bukovina was inhabited by a compact Ukrainian population that outnumbered Romanians,[54] while Bessarabia was regarded as having a Romanian majority, even though the larger part of the population adopted a "Moldavian" identity.[55]

In the early hours of June 27, Carol II had a meeting with his prime minister, Gheorghe Tătărescu, and minister for external affairs, Ion Gigurtu, after which he summoned the ambassadors of Italy and Germany. The King communicated his wish to stand against the Soviet Union and asked that their countries influence Hungary and Bulgaria in the hope of not declaring war against Romania in order to reclaim Transylvania and Dobrudja. Stating that it would be “in the name of peace” to accede to Soviet demands, the ambassadors urged the King to stand down.[56]

On the same day, the Romanian government replied, suggesting it would agree to "immediate negotiations on a wide range of questions".[57] On June 27, a second Soviet ultimatum note put forward a specific time frame, requesting the evacuation of the Romanian government from Bessarabia and northern Bukovina within four days.

On the morning of June 28, 1940, following advice by both Germany and Italy, the Romanian government, led by Gheorghe Tătărescu, under the semi-authoritarian rule of King Carol II, agreed to submit to the Soviet demands. Without explanation, the Soviet forces also occupied the Hertza Region, part of the Romanian Old Kingdom, which was neither in Bessarabia, nor Bukovina.

The decision to accept the Soviet ultimatum and to commence a "withdrawal" (avoiding the usage of the word to cede) from Bessarabia and northern Bukovina was deliberated upon by the Romanian Crown Council during the night of June 27–28, 1940. The second (decisive) vote outcome, according to the journal of King Carol II, was:

- Reject the ultimatum: Ștefan Ciobanu, Silviu Dragomir, Victor Iamandi, Nicolae Iorga, Traian Pop, Ernest Urdăreanu

- Accept the ultimatum: Petre Andrei, Constantin Anghelescu, Constantin Argetoianu, Ernest Ballif, Aurelian Bentoiu, Mircea Cancicov, Ioan Christu, Mitiță Constantinescu, Mihail Ghelmegeanu, Ion Gigurtu, Constantin C. Giurescu, Nicolae Hortolomei, Ioan Ilcuș (minister of defence), Ion Macovei, Gheorghe Mironescu, Radu Portocală, Mihai Ralea, Victor Slăvescu, Gheorghe Tătărescu (prime-minister), Florea Țenescu (chief of the General Staff of the Army)

- Abstained: Victor Antonescu.

During the same night, Carol II also convinced Alexandru Vaida-Voevod to be sworn in as minister. Vaida, along with all of the above, signed the final Crown Council recommendation, in which Carol II ordered the Army to stand down.

Romanian withdrawal

On June 28, at 9:00, communique no. 25 of the General Staff of the Romanian Army officially announced the contents of the ultimatum to the population, its acceptance by the Romanian government, and the intent to evacuate the army and administration to the Prut River. By 14:00, three key cities — Chişinău, Cernăuți and Cetatea Albă — had to be turned over to the Soviets. The military installations and casemates, built during a 20-year period for the event of a Soviet attack, were relinquished without a fight, the Romanian Army being placed by its command under strict orders not to respond to provocation.

A part of the population left the regions along with the Romanian administration and over 70,000 request for repatriation to Romania were recorded afterwards. According to the April 1941 Romanian census, the total number of refugees from the evacuated territories amounted to 68,953. On the other hand, by early August 1940 between 112,000 and 149,974 people left the other territories of Romania for the Soviet-ruled Bessarabia. This figure comprised mostly natives of the region, but also included Jews who wanted to escape the officially-endorsed Anti-semitism in Romania.[58]

Incorporation of the annexed territories into the USSR

As Romania agreed to satisfy Soviet territorial demands, the second plan was put into action on the morning of June 28. By June 30, the Red Army reached the border along the Prut river. On July 3, the border was closed completely from the Soviet side.

One month after the military occupation, on August 2, 1940, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was established on the main part of the annexed territory, while smaller portions were given to the Ukrainian SSR. Six Bessarabian counties, and small portions of the other three counties, along with parts of the Moldavian ASSR (formerly part of Ukrainian SSR), which was disbanded on that occasion, formed the Moldavian SSR, which became one of 15 union republics of the USSR. The Soviet governmental commission headed by Nikita Khrushchev, the then Communist Party chief of the Ukrainian SSR, allotted Northern Bukovina, Hertsa region, and larger parts of Hotin, Ismail, and Cetatea Albă counties to the Ukrainian SSR.

During 1940–1941, political persecution of certain categories of locals took the form of arrests, executions, and deportations to the eastern parts of the Soviet Union. According to Alexandru Usatiuc-Bulgăr,[59] 32,433 people received a politically motivated sentence, of which 8,360 were sentenced to death, or died during interrogations.

Serious incidents occurred in Northern Bukovina, where attempts by the locals to force the border towards Romania resulted in the Soviet border guards opening fire against unarmed civilians. In one case, at Fântâna Albă, this resulted in a massacre.

The installation of the Soviet administration was also accompanied by major changes in the economic domain, as medium and large commercial and industrial enterprises were nationalised. The Soviet government also instituted a land reform, redistributing 229,752 hectares to 184,715 poor peasant households, and limiting estate size to 20 hectares in the south, and 10 hectares elsewhere. A collectivisation drive was also started in 1941, however, due to the lack of agricultural machinery, the progress was extremely slow, just 3.7% of the peasant households being included in kolkhozes and sovkhozes by midyear.[60] In order to bolster the government's image, a large part of the 1941 budget was directed towards social and cultural needs, with 20% allocated to health services, and 24% to education and literacy campaigns. While the theological institute in Chişinău was closed, six new higher education institutions were created, including a conservatory and a polytechnic. Furthermore, the salaries of industrial workers and administrative personnel were increased two to three times compared to pre-Soviet levels.[61]

Aftermath

International reactions

Of all regional allies, with which Romania had treaties with military clauses, only Turkey replied that it would live up to its treaty obligations by providing support in case of Soviet military aggression.

According to Time from Monday, July 1, 1940,

This week Russian planes began making reconnaissance flights over Bessarabia. Then border clashes were reported all along the Dn[i]estr River. Though the Rumanian Army made a show of resistance for the record, it has no chance of stopping the Russians without help, and Germany had already acknowledged Russia's claim to Bessarabia in secret deals last year. Romania had accepted her destiny in the new Europe that Hitler plans. She will also lose Transylvania to Hungary and probably a part of the Dobruja to Bulgaria. (...) Russia's Sphere. Russia was preoccupied with consolidating her own position to the east of Hitler's Europe. On the heels of her occupation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, those three countries set up left-wing Governments that looked like steppingstones to complete sovietization. (...) Germany took the occupation calmly. Germany's calm was doubtless real, since last year's deals gave Russia a free hand in the Baltic as well as Bessarabia.[62]

Political developments in Romania

The territorial concessions of 1940 produced deep sorrow and resentment among Romanians, and hastened the decline in popularity of the regime led by King Carol II of Romania. Three days after the annexation, Romania renounced the 1939 Anglo-French guarantee. A new government of Ion Gigurtu was sworn in on July, 5th, 1940, which withdrew the country from the League of Nations (July 11, 1940), and announced the desire to join the Axis camp (July 13, 1940). A series of measures taken by Romanian Prime Minister Ion Gigurtu, including official persecution of Jews inspired by the German Nuremberg Laws in July and August 1940, failed to sway Germany from awarding Northern Transylvania to Hungary in the Second Vienna Award on August 30, 1940.

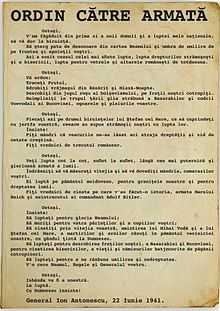

This led to a near uprising in the country. On September 5, King Carol II proposed to General (later Marshal) Ion Antonescu, the chief of the Army, to form a new government. Antonescu's first act was to force the King to abdicate (for the fourth and last time) and flee Romania. An alliance government was formed by Ion Antonescu with remnants of the Iron Guard Legionary Movement (partly destroyed in 1938; see The Iron Guard#A bloody struggle for power), an anti-Semitic fascist party, and took power on September 6, 1940. Mihai, son of Carol II, succeeded him as King of Romania. The country was declared a National Legionary State. Between October 1940 and June 1941, around 550,000 German troops entered Romania. In November, Antonescu signed the Tripartite (Axis) Pact, tying Romania militarily to Germany, Italy, and Japan. In January 1941, the Legionary Movement attempted a coup, which failed and placed Antonescu firmly in power with the approval of Hitler. The authoritarian regime of Antonescu (1940–1944) did not restore political parties and elected democracy; it only co-opted several individual civilians in the government.

Overall, the desire to regain the lost territories was the deciding factor leading to the entry of Romania into World War II on the side of the Axis against the Soviet Union.

Romanian recovery of Bessarabia and wartime administration

On June 22, 1941, Romania participated alongside Hungary, and Italy on the side of the Axis Powers in the German invasion of the Soviet Union, in order to recover Bessarabia and Bukovina.[63] This was accomplished by July 26, 1941.

The King Michael of Romania, his mother Helen, and Mihai Antonescu joined the opening ceremony of the monumental Liberation Tower in Ghidighici, on November 1, 1942.[64]

On July 27, 1941, despite disagreement from all political parties,[65] Romania's military dictator Ion Antonescu ordered the Romanian Army to continue the war eastward into proper Soviet territory to fight at Odessa, Crimea, Kharkov, Stalingrad and the Caucasus. Between late 1941 and early 1944, Romania occupied and administered the region between the Dniester and Southern Bug rivers, known as Transnistria, and sent expedition troops to several different areas to support the German advance further into the USSR.

On the backdrop of increased anti-Semitism in Romania in the late 1930s, the government of Ion Antonescu officially adopted the myth of Jewish Bolshevism, making Jews responsible for the territorial losses Romania suffered during the summer of 1940. As a results, the government, in agreement with Germany, embarked in a campaign to "cleanse" the recaptured territories by massively deporting and/or killing the Jews of Bukovina and Bessarabia who did not flee to the interior of the Soviet Union before Romania regained the territory in July 1941. Only in 1941, between 45,000 and 60,000 Jews were killed in Bessarabia and Bukovina by the Romanian and German armies. Surviving Jews were quickly gathered in temporary ghettos and 154,449 to 170,737 were then deported to Transnistria; only 49,927 of them were still alive on September 16, 1943. Only 19,475 Jews of the regions of Bukovina and of the Dorohoi county survived in these territories in 1941-1944 without being deported, most of them in Cernăuți. Romanian gendarmerie (riot police) units also participated, along German troops and local militias, in the destruction of the Jewish community in Transnistria, by murdering between 115,000 and 180,000 local Jews.(See History of the Jews in Moldova#The Holocaust).[66]

In 1941-1944, many young male inhabitants of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina were recruited into the Romanian Army. From February to August 1944, hostilities took place properly in the region, as the Romanians attempted to hold the territory from being overrun by the Soviet Union. In total, during World War II, the Romanian Army has lost 475,070 people on the Eastern Front, of which 245,388 were killed in action, disappeared, or died in hospitals or non-battle circumstances, and 229,682 (according to Soviet archival documents) were taken prisoners of war by the Red Army. Of the latter, 187,367 were counted as Romanian POWs in NKVD camps (on April 22, 1956, 54,612 were counted as died in captivity, and 132,755 as freshly released), 27,800 were counted as Romanians released by the Front-levels of the Soviet Army, while 14,515 as Moldovans released by the Front-levels of the Soviet Army.[67]

Restoration of Soviet administration

During the first part of 1944, the Soviet Union gradually took over the territory through the Uman–Botoșani and Jassy-Kishinev offensives. On August 23, 1944, with Soviet troops advancing and the Eastern Front falling within Romania's territory, a coup led by King Michael, with support from opposition politicians and the army, deposed the Antonescu dictatorship, ceased military actions against the Allies, and later put Romania's battered armies on their side. In the days immediately after the coup, as Romania's action was unilateral and no armistice had been agreed with the Allied Powers, the Red Army continued to treat the Romanian troops as enemy combatants, while in the confusion, the Romanian troops were not opposing them. As a consequence, the Soviets took a large number of Romanian troops as prisoners of war with little or no fight. Some of the prisoners were Bessarabian-born. Michael acquiesced to Soviet terms, and Romania was occupied by the Soviet Army.

From August 1944 to May 1945, ca. 300,000 people were conscripted into the Soviet Army from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, and were sent to fight against Germany in Lithuania, East Prussia, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. Some 100,000 were killed, while some other 100,000 were wounded.

In 1947, as part of the Paris Peace Treaties, Romania and the Soviet Union signed a border treaty, confirming the border fixed in 1940.[68] Several additional uninhabited islands in the Danube Delta, as well as the Snake Island, not mentioned in the Treaty, were transferred from the Communist Romania to the Soviet Union in 1948.

Social and cultural consequences

At the moment of the Soviet occupation, the regions had a total population of 3,776,309 inhabitants. According to Romanian official statistics, this was distributed among the ethnic groups as follows: Romanians (53.49%), Ukrainians and Ruthenians (15.3%), Russians (10.34%), Jews (7.27%), Bulgarians (4.91%), Germans (3.31%), others (5.12%).[69][70]

Population movements

During the Soviet takeover in 1940, Bessarabian Germans (82,000) and Bukovinain Germans (40,000-45,000) were repatriated to Germany at the request of Hitler's government. Some of them were forcibly settled by the Nazis in the German-occupied Poland (they preferred proper German regions), and had to move again in 1944-1945. The people affected by the resettlement were not persecuted, but they were given no choice to stay or live, and had to change their entire livelihood within weeks or even days.

Up to 70,000 people fled from Bessarabia and northern Bukovina to the rest of Romania on 28 June 1940 and in the following days, most of them returned afterwards in 1941. However, faced with the advancing Soviet troops in 1944, and fearing political repressions or deportations, several hundred thousand people moved westward to the remaining territory of Romania.

Deportations and political repression

Deportations of locals on grounds of belonging to the intelligentsia or kulak classes, or of having anti-Soviet nationalist ideas occurred almost daily throughout 1940-41 and 1944–1950, and with less frequency in 1950-1956. These deportations touched all local ethnic groups: Romanians, Ukrainians, Russians, Jews, Bulgarians, Gagauz. Significant deportations happened on three separate occasions: according to Alexandru Usatiuc-Bulgăr,[59] 29,839 people were deported to Siberia on 13 June 1941. In total, in the first year of Soviet occupation,[71] no fewer than 86,604 people from Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and Hertsa Region suffered political repression.[72] This number is close to the one calculated by Russian historians following documents in the Moscow archives, of ca. 90,000 people repressed, arrested or deported in the first year of Soviet occupation.[73] The greater part of this figure (53,356) was represented by forced conscription for labour across the Soviet Union.[74] The classification of such labourers as victims of political repression is however disputed, as the poverty of the locals and the Soviet propaganda are also considered important factors leading to the emigration of the local work force.[75] The arrests continued even after 22 June 1941.[76][77]

Based on post-war statistics, historian Igor Cașu has shown that Moldovans/Romanians comprised roughly 50 percent of the deportees, with the rest being Jews, Russians, Ukrainians, Gagauzes, Bulgarians and Roma people. Considering the ethnic make-up of the region, he concludes that pre- and post-war repression was not directed at any specific ethnic or national group, but could be characterised as "genocide" or "crime against humanity". The 1941 deportation targeted "anti-Soviet elements" and comprised former representatives of the Romanian interwar administration (policemen, gendarmes, prison guards, clerks), large land-owners, tradesmen, former officers of the Romanian, Polish and Tsarist armies, and people who had defected the Soviet Union before 1940. Kulaks would only become main targets of repression in the post-war period.[74] Before Soviet archives were made accessible, R. J. Rummel had estimated between 1940 and 1941, 200,000 to 300,000 Romanian Bessarabians were persecuted, conscripted into forced labor camps, or deported with the entire family, of whom 18,000 to 57,000 were supposedly killed.[78]

Religious persecution

After the installation of the Soviet administration, the religious life in Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina underwent a persecution similar to the one in Russia between the two World Wars. In the first days of occupation, certain population groups welcomed the Soviet power and some of them joined the newly established Soviet nomenklatura, including NKVD, the Soviet political police. The latter has used these locals to find and arrest numerous priests.[79] Other priests were arrested and interrogated by the Soviet NKVD itself, then deported to the interior of the USSR, and killed. Research on this subject is still at an early stage. As of 2007, the Christian Orthodox church has granted the martyrdom to ca. 50 clergymen who died in the first year of Soviet rule (1940–1941).[79]

Legacy

In the Soviet Union

In Soviet historiography, the chain of events that led to the creation of the Moldavian SSR was described as a "liberation of the Moldovan people from a 22-year-old occupation by boyar Romania." During 1940-1989, the Soviet authorities promoted the events of June 28, 1940 as a "liberation", and the day itself was a holiday in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic.

However, in 2010, the Russian political analyst Leonid Mlecin stated that the term occupation is not adequate, but that "it is more an annexation of a part of the territory of Romania".[80]

Pre-independence Moldova

On June 26–28, 1991, a unique and widely mediated International Conference "Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and its consequences for Bessarabia" took place in Chișinău, gathering renowned historians such as Nicholas Dima, Kurt Treptow, Dennis Diletant, Michael Mikelson, Stephen Bowers, Lowry Wymann, Michael Bruchis, in addition to Moldovan, Soviet and Romanian historians. An informal Declaration of Chișinău was adopted, according to the which the Pact and its Secret Protocol "constituted the appogeum of collaboration between the Soviet Union an Nazi Germany, and following these agreements, Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina were occupied by the Soviet Army on June 28, 1940 as a result of ulitmative notes addressed to the Romanian government". These acts were given the characteristic of a "pregnant manifestation of imperialist policy of annexion and dictat, a shameless aggression against the sovereignty (...) of neighboring states, members of the League of Nations. The Stalinist aggression constituted a serious breach of the legal norms of behavior of states in international relations, of the obligations assumed under the Briand-Kellog Pact of 1928, and under the London Convention on the Definition of the Agressor of 1933." The declaration stated that "the Pact and the Secret Additional Protocol are legally null ab initio, and their consequences must be eliminated." For the latter, it called for "political solutions that would lead to the elimination of the acts of injustice and abuse committed through the use of force, dictat and annexions, ... [solutions] in full consensus with the principles of the [1975] Final Act of Helsinki, and the [1990] Paris Carta for a new Europe".[81][82]

United States

On June 28, 1991, the US Senate voted a resolution sponsored by Senators Jesse Helms (R-NC) and Larry Pressler (R-SD), members of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, which recommended the US Government to

- "1. support the right to self-determination of the people of Moldova and Northern Bukovina, occupied by the Soviets, and to draft a decision to this end;

- "2. support the future efforts of the Government of Moldova to negotiate, if it desires so, a peaceful reunification of Moldova and northern Bukovina with Romania, as established in the Treaty of Paris (1920), respecting the existing norms of international law and principle 1 of the Helsinki Act."

In the clauses of this Senate resolution it has been stated among other things that "(...) The armed forces of the Soviet Union invaded the Kingdom of Romania and occupied Eastern Moldova, Norther Bukovina and Hertsa Region. (...) The annexation was prepared beforehand in a Secret Agreement to a Non-Aggression Treaty signed by the Governments of the Soviet Union and the German Reich on August 23, 1939. (...) Between 1940 and 1953 hundreds of thousand of Romanian from Moldova and Northern Bukovina were deported by the USSR to Central Asia and Siberia (...)"[83][84][85]

Modern Moldova

- Mihai Ghimpu, interim president of Moldova in 2010 has decreed June 28, 1940, as the Soviet Occupation Day. The move was met with disapproval and calls for the decree's revocation inside the ruling coalition, and calls for Ghimpu's resignation among the opposition parties. Dorin Chirtoacă, mayor of Chişinău and member of the same party as Ghimpu, ordered the erection of a memorial stone in the National Assembly Square, in front of the parliament building, where a Lenin monument used to stand.[86] The members of the coalitions argued that the time has not come for such a decree and that it would only help the communists win more votes.[87] The Academy of Sciences of Moldova declared that "in the view of recent disagreements regarding June 28, 1940 [...] we must take action and inform the public opinion about the academic community views." The Academy declared that: "Archival documents and historical research of international experts shows that the annexation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina was designed and built by Soviet Command as a military occupation of these territories. Ordinance of Interim President Michael Ghimpu reflects, in principle, the historical truth."[88]

- On June 30, 2010, First Vlad Filat Cabinet decided to create the Museum of Victims of Communism[89] and Vlad Filat opened the museum on July 6, 2010.[90]

See also

- European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism

- Declaration on Crimes of Communism

- Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism

- Vilnius Declaration

- Comparison of Nazism and Stalinism

Notes

- ↑ King 2000, pp. 91–95

- ↑ Final Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania

- ↑ Bossy, G.H., Bossy, M-A. Recollections of a Romanian diplomat, 1918-1969, Volume 2, Hoover Press, 2003.

- ↑ Joseph Rothschild, East Central Europe between the two World Wars University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1977; ISBN 0-295953-57-8, p.314

- ↑ James Stuart Olson, Lee Brigance Pappas, Nicholas Charles Pappas (1994). An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 484. ISBN 9780313274978.

- ↑ The Armistice Agreement with Rumania; September 12, 1944

- ↑ United States Department of State. Foreign relations of the United States, 1946. Paris Peace Conference: documents Volume IV (1946)

- ↑ Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Moldova

- ↑ История Республики Молдова. С древнейших времён до наших дней = Istoria Republicii Moldova: din cele mai vechi timpuri pină în zilele noastre / Ассоциация учёных Молдовы им. Н. Милеску-Спэтару — изд. 2-е, переработанное и дополненное. — Кишинёв: Elan Poligraf, 2002. — С. 146. — 360 с. — ISBN 9975-9719-5-4.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 King 2000, p. 24

- ↑ Keith Hitchins, Rumania: 1866-1947 (Oxford History of Modern Europe). 1994, Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822126-6

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, pp. 32–33

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Prusin 2010, p. 84

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 34

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, pp. 35–36

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Prusin 2010, p. 86

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Mitrasca 2002, p. 36

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 85

- ↑ Charles Upson Clark, "Bessarabia", Chapter XIX, New York, 1926, Chapter 19

- ↑ Petre Cazacu, Moldova dintre Prut și Nistru 1812-1918, Chișinău, Știinţa, 1992, pp. 345-346

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Mitrasca 2002, p. 35

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Wim P. van Meurs, The Bessarabian question in communist historiography, East European Monographs, 1994, p. 67

- ↑ Cristina Petrescu, "Contrasting/Conflicting Identities:Bessarabians, Romanians, Moldovans" in Nation-Building and Contested Identities, Polirom, 2001, p. 156

- ↑ King 35

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 109

- ↑ Livezeanu 2000, p. 56

- ↑ Livezeanu 2000, pp. 56–57

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Livezeanu 2000, p. 58

- ↑ Livezeanu 2000, p. 57

- ↑ Richard K. Debo, Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-1921, McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, ISBN 0-7735-0828-7, pp. 113-114.

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 110

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 72

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 86

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, pp. 111–112

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 111

- ↑ Malbone W. Graham (October 1944). "The Legal Status of the Bukovina and Bessarabia". The American Journal of International Law (American Society of International Law) 38 (4): 667–673. doi:10.2307/2192802. Retrieved 2009-12-09; Scholar search. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 411

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 345

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, pp. 368–369

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, pp. 345,386

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 391

- ↑ Kellogg-Briand Pact, at Yale University.

- ↑ League of Nations Treaty Series, 1929, No. 2028.

- ↑ League of Nations Treaty Series, 1928, No. 2137.

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 124

- ↑ Marcel Mitrasca|2002, Moldova: A Romanian Province under Russian Rule. Diplomatic History form the Archives of the Great Powers, Algora Publishing

- ↑ Keith Hitchins, Rumania, 1866-1947, pp.436-437, Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-19-822126-6, ISBN 978-0-19-822126-5

- ↑ Mitrasca 2002, p. 137

- ↑ German-Soviet Non-Aggression Treaty of August 23, 1939. Complete text online at wikisource.org.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Ioan Scurtu,Istoria Basarabiei de la inceputuri pana in 2003, Editura Institutului Cultural Roman, pg. 327

- ↑ (Russian) Ультимативная нота советского правительства румынскому правительству 26 июня 1940 г.

- ↑ (Romanian) "Soviet Ultimata and Replies of the Romanian Government", in Ioan Scurtu, Theodora Stănescu-Stanciu, Georgiana Margareta Scurtu, Istoria Românilor între anii 1918-1940, University of Bucharest, 2002

- ↑ Livezeanu 2000, p. 50

- ↑ Livezeanu 2000, p. 92

- ↑ Ioan Scurtu, Istoria Basarabiei de la inceputuri pana in 2003, Editura Institutului Cultural Roman, pg. 333

- ↑ The actual result of the first vote was 11 Reject the ultimatum, 10 Accept the ultimatum, 5 For negotiations with the USSR, and 1 Abstained.

- ↑ Dobrincu, Dorin (21 February 2013). "Consecințe ale unei cedări lipsite de onoare". Revista 22 (in Romanian). Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Alexandru Usatiuc-Bulgăr "Cu gîndul la "O lume între două lumi": eroi, martiri, oameni-legendă" ("Thinking of 'A World between Two Worlds': Heroes, Martyrs, Legendary People"), Publisher: Lyceum, Orhei (1999) ISBN 9975-939-36-8

- ↑ Caşu, Igor (2000). "Politica națională" în Moldova Sovietică. Chişinău: Cartdidact. p. 25-26. ISBN 9789975940290.

- ↑ Caşu, Igor (2000). "Politica națională" în Moldova Sovietică. Chişinău: Cartdidact. p. 34-36. ISBN 9789975940290.

- ↑ "Hitler's Europe", Time, Monday, July 1, 1940

- ↑ "Background Note: Romania", United States Department of State, Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, October 2007. The text says: "Romania entered World War II on the side of the Axis Powers in June 1941, invading the Soviet Union to recover Bessarabia and Bukovina, which had been annexed in 1940."

- ↑ Vasile Șoimaru. "Turnul Dezrobirii Basarabiei" (in Romanian). Literatura și Arta. Retrieved 2012-02-17.

- ↑ (Romanian) www.worldwar2.ro: Maresal Ion Antonescu

- ↑ "The Holocaust in Romania" (PDF). Final Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. Yad Vashem (The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority). Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ↑ Krivosheyev, Grigoriy (1997). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-280-7.

- ↑ Treaty of Peace with Roumania at Australian Treaty Series 1948, No. 2

- ↑ Viata bucovineana in Ramnicu-Valcea postbelic (Romanian)

- ↑ Atitudinea antiromaneasca a evreilor din Basarabia at historia.ro

- ↑ Comisia Prezidențială pentru Analiza Dictaturii Comuniste din România: Raport Final / ed.: Vladimir, Dorin Dobrincu, Cristian Vasile, București: Humanitas, 2007, ISBN 978-973-50-1836-8, p. 747

- ↑ Igor Cașu, ""Politica națională" în Moldova sovietică", Chișinău, Ed. Cartdidact, 2000, p. 32-33

- ↑ (Russian) Mikhail Semiryaga, "Tainy stalinskoi diplomatii", Moscow, Vysshaya Shkola, 1992, p. 270

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Caşu, Igor (2010). "Stalinist Terror in Soviet Moldavia". In McDermott, Kevin; Stibbe, Matthew. Stalinist Terror in Eastern Europe. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719077760. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ Comisia Prezidențială pentru Analiza Dictaturii Comuniste din România: Raport Final, p. 595

- ↑ "Literatura și Arta", 12 December 1991

- ↑ Report, p. 747-748

- ↑ R. J. Rummel, Table 6.A. 5,104,000 victims during the pre-World War II period: sources, calculations and estimates, Freedom, Democracy, Peace; Power, Democide, and War, University of Hawaii.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 (Romanian) Martiri pentru Hristos, din România, în perioada regimului comunist, Editura Institutului Biblic și de Misiune al Bisericii Ortodoxe Române, București, 2007, pp.34–35

- ↑ Un analist rus recunoaște: URSS a anexat Basarabia la 28 iunie 1940 VIDEO | Historia

- ↑ Mihai Adauge, Alexandru Furtună, Basarabia și Basarabenii, Uniunea Scriitorilor din Moldova, Chișinău, 1991, ISBN 5-88568-022-1, pp. 342-347

- ↑ Dan Dungaciu, p.11

- ↑ Gheorghe E. Cojocaru, Politica externă a Republicii Moldova. Studii., Ediția 2-a, Civitas, Chișinău, 2001, p. 126+128

- ↑ Dan Dungaciu, p. 11-13

- ↑ Resolution project published also in Moldova Suverană, 20 iunie 1991

- ↑ Primăria a instalat în fața Guvernului o piatră în memoria victimelor regimului comunist

- ↑ 28 iunie, zi de ocupație sovietică-Chestiunea zilei-JurnalTV - Prima televiziune de stiri din Republica Moldova

- ↑

- ↑ Prim-ministrul Vlad FILAT a prezidat astăzi ședința ordinară a Guvernului

- ↑ Prim-ministrul Vlad FILAT a participat astăzi la acțiunile consacrate memoriei victimelor deportărilor și represiunilor politice

References

- (English) George Ciorănescu, "40th Anniversary of Annexation of Bessarabia and Northern Bucovina", Radio Free Europe report, July 23, 1980.

- (English) George Ciorănescu, "The Problem of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina during World War II" at the Wayback Machine (archived July 19, 2009), Radio Free Europe report, December 2, 1981.

- Mikhail Meltyukhov, Stalin's Missed Chance

- (Romanian) Andreea Tudorica, Ovidiu Ciutescu, Corina Andriuta, "Giurgiulești, piedică în calea lui Stalin", Jurnalul Naţional, June 26, 2007

- (Romanian) Alexandru Usatiuc-Bulgăr "Cu gîndul la «O lume între două lumi»: eroi, martiri, oameni-legendă" ("Thinking of 'A World between Two Worlds': Heroes, Martyrs, Legendary People"), Publisher: Lyceum, Orhei (1999) ISBN 9975-939-36-8

- King, Charles (2000). The Moldovans. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-9792-2.

- Livezeanu, Irina (2000). Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building, and Ethnic Struggle, 1918-1930. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8688-3.

- Mitrasca, Marcel (2002). Moldova: a Romanian province under Russian rule. New York: Agora. ISBN 978-1-892941-86-2.

- Prusin, Alexander V. (2010). The Lands Between: Conflict in the East European Borderlands, 1870-1992. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929753-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. |

- "Molotov-Ribbentrop pact", from Wikisource

- "Romanian Army in the Second World War"

- International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania: Final Report (2004)

- The June/July 1940 Romanian Withdrawal from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina and its Consequences on Interethnic Relations in Romania

- (Romanian) "Text of Litvinov-Titulescu pact"

- (Romanian) "Joachim von Ribbentrop to Viaceslav Molotov, regarding of Bessarabia and Bukovina, June 25, 1940"

- (Romanian) "The Ultimatum notes and Romanian responses"

- Ioan Scurtu (2003). Istoria Basarabiei de la începuturi până în 2003. Editura Institutului Cultural Român.

| |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||