Soviet art

Soviet art is the visual art that was produced in the Soviet Union.

Soviet Avant-Garde art

During the Russian Revolution a movement was initiated to put all arts to service of the dictatorship of the proletariat. The instrument for this was created just days before the October Revolution, known as Proletkult, an abbreviation for "Proletarskie kulturno-prosvetitelnye organizatsii" (Proletarian Cultural and Enlightenment Organizations). A prominent theorist of this movement was Aleksandr Bogdanov. Initially Narkompros (ministry of education), which was also in charge of the arts, supported Proletkult. However the latter sought too much independence from the ruling Communist Party of Bolsheviks, gained negative attitude of Vladimir Lenin, by 1922 declined considerably, and was eventually disbanded in 1932.

The ideas of Proletkult attracted the interests of Russian avantgarde, who strived to get rid of the conventions of "bourgeois art". Among notable persons of this movement was Kazimir Malevich. However the ideas of the avantgarde eventually clashed with the newly emerged state-sponsored direction of Socialist Realism.

In search of new forms of expression, the Proletkult organisation was highly eclectic in its art forms, and thus was prone to harsh criticism for inclusion of such modern directions as impressionism and cubism, since these movements existed before the revolution and hence were associated with "decadent bourgeois art".

Among early experiments of Proletkult was pragmaic aesthetic of industrial art, the prominent theoretist being Boris Arvatov.

Another group was UNOVIS, a very short-lived but influential collection of young artists led by Kasimir Malevich in the 1920s.

Socialist realism

Officially approved art was required to follow the doctrine of Socialist Realism. In the spring of 1932 the Central Committee of the Communist Party decreed that all existing literary and artistic groups and organizations should be disbanded and replaced with unified associations of creative professions. Accordingly, the Moscow and Leningrad Union of Artists was established on August 1932, which brought the history of post-revolutionary art to a close. The epoch of Soviet art began.[1]

The best known Soviet artists were Isaak Brodsky, Alexander Samokhvalov, Boris Ioganson, Aleksandr Deyneka, Aleksandr Laktionov, Yuri Neprintsev and other painters from Moscow and Leningrad School.[2] Moscow artist Aleksandr Gerasimov during his career produced a large number of heroic paintings of Joseph Stalin and other members of the Politburo. Nikita Khrushchev later alleged that Kliment Voroshilov spent more time posing in Gerasimov's studio than he did attending to his duties in the People's Commissariat of Defense. Gerasimov's painting shows a mastery of classical representational techniques.

However, art exhibitions of 1935–1960 disprove the claims that artistic life of the period was suppressed by the ideology and artists submitted entirely to what was then called ‘social order’. A great number of landscapes, portraits, genre paintings and studies exhibited at the time pursued purely technical purposes and were thus free from any ideology. Thematic painting was also approached in a similar way.[3]

In the post-war period between the mid-fifties and sixties, the Leningrad school was approaching its apex. Artists who had graduated from the Academy (Repin Institute of Arts) in the 1930s–50s were in their prime. They were quick to present their art, they strived for experiments and were eager to appropriate a lot and to learn even more. Their time and contemporaries, with all its images, ideas and dispositions found it full expression in portraits by Lev Russov, Victor Oreshnikov, Boris Korneev, Semion Rotnitsky, Vladimir Gorb, Engels Kozlov, landscapes by Nikolai Timkov, Vladimir Ovchinnikov, Sergei Osipov, Alexander Semionov, Arseny Semionov, Nikolai Galakhov, genre paintings by Nikolai Pozdneev, Yuri Neprintsev, Yevsey Moiseenko, Andrey Milnikov. Art of this period showed extraordinary taste for life and creative work.

In 1957, the first all-Russian Congress of Soviet artists took place in Moscow. In 1960, the all-Russian Union of Artists was organized. Accordingly, these events influenced the art life in Moscow, Leningrad and province. The scope of experimentation was broadened; in particular, this concerned the form and painterly and plastic language. Images of youths and students, rapidly changing villages and cities, virgin lands brought under cultivation, grandiose construction plans being realized in Siberia and the Volga region, great achievements of Soviet science and technology became the chief topics of the new painting. Heroes of the time – young scientists, workers, civil engineers, physicians – become the most popular heroes of paintings.

At this period, life provided artists with plenty of thrilling topics, positive figures and images. Legacy of many great artists and art movements became available for study and public discussions again. This greatly broadened artists’ understanding of the realist method and widened its possibilities. It was the repeated renewal of the very conception of realism that made this style dominates in the Russian art throughout its history. Realist tradition gave rise to many trends of contemporary painting, including painting from nature, "severe style" painting and decorative art. However, during this period impressionism, postimpressionism, cubism and expressionism also had their fervent adherents and interpreters.[4]

Soviet Nonconformist Art

The death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Nikita Khrushchev's Thaw, paved the way for a wave of liberalization in the arts throughout the Soviet Union. Although no official change in policy took place, artists began to feel free to experiment in their work, with considerably less fear of repercussions than during the Stalinist period.

In the 1950s Moscow artist Ely Bielutin encouraged his students to experiment with abstractionism, a practice thoroughly discouraged by the Artists' Union, which strictly enforced the official policy of Socialist Realism. Artists who chose to paint in alternative styles had to do so completely in private and were never able to exhibit or sell their work. As a result, Nonconformist Art developed along a separate path than the Official Art that was recorded in the history books.

Life magazine published two portraits by two painters, who to their mind, were most representative of Russian Arts of the period: it was Serov, an official Soviet icon and Anatoly Zverev, an underground Russian avant-garde expressionist. Serov's portrait of Vladimir Lenin and Zverev's selfportrait were associated by many with an eternal Biblical struggle of Satan and Saviour. When Khrushchev learned about the publication he was outraged and forbade all contacts with Western visitors, closed down all semi legal exhibitions. And of course Zverev was the main target of his outrage.

The Lianozovo Group was formed around the artist Oscar Rabin in the 1960s and included artists such as Valentina Kropivnitskaya, Vladimir Nemukhin, and Lydia Masterkova. While not adhering to any common style, these artists sought to faithfully express themselves in the mode they deemed appropriate, rather than adhere to the propagandistic style of Socialist Realism.

Tolerance of Nonconformist Art by the authorities underwent an ebb and flow until the ultimate collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Artists took advantage of the first few years after the death of Stalin to experiment in their work without the fear of persecution. In 1962, artists experienced a slight setback when Nikita Khrushchev appeared at the exhibition of the 30th anniversary of the Moscow Artist's Union at the Manege exhibition hall. Among the customary works of Socialist Realism were a few abstract works by artists such as Ernst Neizvestny and Eli Beliutin, which Khrushchev criticized as being "shit," and the artists for being "homosexuals." The message was clear: artistic policy was not as liberal as everyone had hoped.

Unfortunately, the history of late Soviet art has been dominated by politics and simplistic formulae. Both within the artworld and the general public, very little consideration has been given to the aesthetic character of the work produced in the USSR in the 1970s and 1980s. Instead, the official and unofficial art of the period usually stood in for either "bad" or "good" political developments. A more nuanced picture would emphasize that there were numerous competing groups making art in Moscow and Leningrad throughout this period. The most important figures for the international art scene have been the Moscow artists Ilya Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, Andrei Monastyrsky, Vitaly Komar and Aleksandr Melamid.

The most infamous incident regarding nonconformist artists in the former Soviet Union was the 1974 Bulldozer Exhibition, which took place in a park just outside of Moscow, and included work by such artists as Oscar Rabin, Komar and Melamid, Alexandr Zhdanov, Nikolai Smoliakov and Leonid Sokov. The artists involved had written to the authorities for permission to hold the exhibition but received no answer to their request. They decided to go ahead with the exhibition anyway, which consisted solely of unofficial works of art that did not fit into the rubric of Socialist Realism. The KGB put an end to the exhibition just hours after it opened by bringing in bulldozers to completely destroy all of the artworks present. Fortunately for the artists, the foreign press had been there to witness the event. The world-wide coverage of it forced the authorities to permit an exhibition of Nonconformist Art two weeks later in Izmailovsky Park in Moscow.

A few West European collectors, supported during the 60th and the 70th and until 1988 (the year of the Perestroika) many of the artists in the old Soviet Union. One of the leading collectors and philanthropists were the couple Kenda and Jacob Bar-Gera. The Bar-Gera Collection consists of some 200 works of 59 Soviet Russian artists of who did not want to embrace the official art directive of the post-Stalinist Soviet Union. Kenda and Jacob Bar-Gera, both are survivors of the holocaust, supported these partially persecuted artists by sending them money or painting material from Germany to the Soviet Union. Even though the Kenda and Jacob did not meet the artists in person, they bought many of their paintings and other art objects. The works were smuggled to Germany by hiding them in the suitcases of diplomats, traveling businessmen, and students, thus making the Bar-Gera Collection of Russian Non-Conformists among the largest of its kind in the world. Among others, the collection content works of Bachtschanjan Vagritsch, Jankilevskij Wladimir,Rabin Oskar, Batschurin Ewganij, Kabakov Ilja, Schablavin Sergei, Belenok Piotr, Krasnopevcev Dimitrij, Schdanov Alexander, Bitt Galina, Kropivnitzkaja Walentina, Schemjakin Michail, Bobrowskaja Olga, Kropivnitzkij Lew,Schwarzman Michail, Borisov Leonid, Kropiwnizkij Jewgenij, Sidur Vadim, Bruskin Grischa, Kulakov Michail, Sitnikov Wasili, and many others.

By the 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of Perestroika and Glasnost made it virtually impossible for the authorities to place restrictions on artists or their freedom of expression. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the new market economy enabled the development of a gallery system, which meant that artists no longer had to be employed by the state, and could create work according to their own tastes, as well as the tastes of their private patrons. Consequently, after around 1986 the phenomenon of Nonconformist Art in the Soviet Union ceased to exist.

See also

- List of Russian artists

- List of painters of Saint Petersburg Union of Artists

- List of the Russian Landscape painters

- Fine Art of Leningrad

- Leningrad School of Painting

- Soviet fashion design

Footnotes

- ↑ Sergei V. Ivanov. Unknown Socialist Realism: The Leningrad School, pp. 28–29. ISBN 5-901724-21-6, ISBN 978-5-901724-21-7.

- ↑ Segei V. Ivanov. The Leningrad School of painting 1930 – 1990s. Historical outline.

- ↑ Vern G. Swanson, Soviet Impressionist Painting. Woodbridge, England: Antique Collectors' Club, 2008; p. 400.

- ↑ Sergei V. Ivanov. The Leningrad School of painting 1930 – 1990s. Historical outline.

Further reading

- Lynn Mally Culture of the Future: The Proletkult Movement in Revolutionary Russia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- Norton Dodge and Alla Rosenfeld, eds. From Gulag to Glasnost: Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1995.

- George Costakis Collection. "Russian Avant-Garde Art". New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Gallery

-

.jpg)

K. Petrov-Vodkin. Death of a Comissary

-

.jpg)

K. Petrov-Vodkin. Petrograd Madonna

-

A. Rylov. In the Blue Expanse (1918)

-

I. Brodsky. Worker of Dneprostroy

-

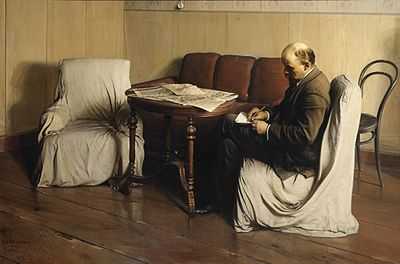

I. Brodsky. Lenin in Smolny (1930)

-

M. Grekov. Trumpeter and standard-bearer

External links

- Soviet avant-garde – video

- Book of Lynn Mally on Proletkult at California Digital Library

- Soviet art at the Russian Art Gallery

- Soviet Posters with history references

- Soviet World War II Paintings

- Sergei V. Ivanov. The Leningrad School of painting 1930 – 1990s. Historical outline.

- Lili Brochetain collection of non conformist art

- Electronic museum of russian posters art Collection of Advertising, Political, Military, Social posters from 1880 to current time

- Oleg Vassiliev Official Site

- Aleksandr Kosolapov Official Site

- Exhibition Back in the USSR-The Heirs of Unofficial Art , Venezia 2009 dedicated to the memory of the greatest collector of unofficial art Leonid Talochkin (1936-2002).