Soviet Union

| Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Other names | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Союз Советских Социалистических Республик Soyuz Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respublik | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto Пролетарии всех стран, соединяйтесь! (Translit.: Proletarii vsekh stran, soyedinyaytes'!) English: Workers of the world, unite! (literally: Proletarians of all countries, unite!) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem "The Internationale" (1922–1944) "State Anthem of the Soviet Union" (1944–1991) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) The Soviet Union after World War II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Moscow | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Russian, many others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | None (state atheism)[2] (see text) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Marxist–Leninist single-party state[3][4][5][6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1922–1952 | Joseph Stalin (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1990–1991 | Vladimir Ivashko (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head of State | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1922–1938 | Mikhail Kalinin (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1988–1991 | Mikhail Gorbachev (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head of Government | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1922–1924 | Vladimir Lenin (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1991 | Ivan Silayev (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Supreme Soviet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | Upper house | Soviet of the Union | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | Lower house | Soviet of Nationalities | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period / World War II / Cold War | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | Treaty of Creation | 30 December 1922 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | Union dissolved | 26 December 1991[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1991 | 22,402,200 km² (8,649,538 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1991 est. | 293,047,571 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density | 13.1 /km² (33.9 /sq mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Soviet ruble (руб) (SUR) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .su1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Calling code | +7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

For details on the succession of states see below. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (Russian: Сою́з Сове́тских Социалисти́ческих Респу́блик, tr. Soyuz Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respublik; IPA: [sɐˈjus sɐˈvʲɛtskʲɪx sətsɨəlʲɪsˈtʲitɕɪskʲɪx rʲɪˈspublʲɪk]) abbreviated to USSR (Russian: СССР, tr. SSSR) and SU (Russian: СС, tr. SS) or shortened to the Soviet Union (Russian: Сове́тский Сою́з, tr. Sovetskij Soyuz; IPA: [sɐ'vʲetskʲɪj sɐˈjʉs]), was a Marxist–Leninist state[3][4][5][6] on the Eurasian continent that existed between 1922 and 1991. It was governed as a single-party state by the Communist Party with Moscow as its capital.[8] A union of multiple subnational Soviet republics, its government and economy were highly centralized.

The Soviet Union had its roots in the Russian Revolution of 1917, which overthrew the Russian Empire. The Bolsheviks, the majority faction of the Social Democratic Labour Party, led by Vladimir Lenin, then led a second revolution which overthrew the provisional government and established the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (renamed Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1936), beginning a civil war between pro-revolution Reds and counter-revolution Whites. The Red Army entered several territories of the former Russian Empire, and helped local Communists take power through soviets that nominally acted on behalf of workers and peasants. In 1922, the Communists were victorious, forming the Soviet Union with the unification of the Russian, Transcaucasian, Ukrainian, and Byelorussian republics. Following Lenin's death in 1924, a troika collective leadership and a brief power struggle, Joseph Stalin came to power in the mid-1920s. Stalin suppressed political opposition to him, committed the state ideology to Marxism–Leninism (which he created) and initiated a centrally planned economy. As a result, the country underwent a period of rapid industrialisation and collectivisation which laid the basis for its later war effort and dominance after World War II.[9] However, Stalin established political paranoia, and introduced arbitrary arrests on a massive scale after which the authorities transferred many people (military leaders, Communist Party members, ordinary citizens alike) to correctional labour camps or sentenced them to execution.

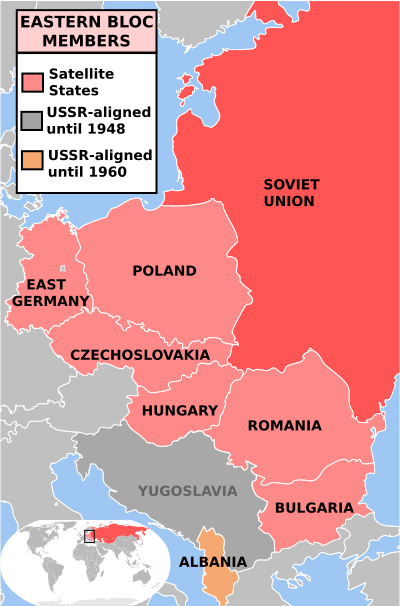

In the beginning of World War II, after the United Kingdom and France rejected an alliance with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany, the USSR signed a non-aggression pact with Germany; the treaty delayed confrontation between the two countries, but was disregarded in 1941 when the Nazis invaded, opening the largest and bloodiest theatre of combat in history. Soviet war casualties accounted for the highest proportion of the conflict in the cost of acquiring the upper hand over Axis forces at intense battles such as Stalingrad. Soviet forces eventually drove through Eastern Europe and captured Berlin in 1945, inflicting the vast majority of German losses.[10] Soviet occupied territory conquered from Axis forces in Central and Eastern Europe became satellite states of the Eastern Bloc. Ideological and political differences with Western Bloc counterparts directed by the United States led to the forming of economic and military pacts, culminating in the prolonged Cold War.

Following Stalin's death in 1953, a period of moderate social and economic liberalization (known as "de-Stalinization") occurred under the administration of Nikita Khrushchev. The Soviet Union then went on to initiate significant technological achievements of the 20th century, including launching the first ever satellite and world's first human spaceflight, which led it into the Space Race. The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis marked a period of extreme tension between the two superpowers, considered the closest to a mutual nuclear confrontation. In the 1970s, a relaxation of relations followed, but tensions resumed when the Soviet Union began providing military assistance in Afghanistan at the request of its new socialist government in 1979. The campaign drained economic resources and dragged on without achieving meaningful political results.[11][12]

In the late 1980s the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, sought to reform the Union and move it in the direction of Nordic-style social democracy,[13][14] introducing the policies of glasnost and perestroika in an attempt to end the period of economic stagnation and democratize the government. However, this led to the rise of strong nationalist and separatist movements. Central authorities initiated a referendum, boycotted by the Baltic republics, Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova, which resulted in the majority of participating citizens voting in favour of preserving the Union as a renewed federation. In August 1991, a coup d'état was attempted by hardliners against Gorbachev, with the intention of reversing his policies. The coup failed, with Russian President Boris Yeltsin playing a high-profile role in facing down the coup, resulting in the banning of the Communist Party. On 25 December 1991, Gorbachev resigned and the remaining twelve constituent republics emerged from the dissolution of the Soviet Union as independent post-Soviet states.[15] The Russian Federation (formerly the Russian SFSR) assumed the Soviet Union's rights and obligations and is recognised as its continued legal personality.[16]

Geography, climate and environment

| ||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Soviet Union | ||||||||||||

|

Leadership |

||||||||||||

|

Governance

|

||||||||||||

|

Judiciary

|

||||||||||||

|

History and politics

|

||||||||||||

|

Society

|

||||||||||||

|

Soviet Union portal | ||||||||||||

With an area of 22,402,200 square kilometres (8,649,500 sq mi), the Soviet Union was the world's largest state, a status that is retained by the Russian Federation.[17] Covering a sixth of the Earth's land surface, its size was comparable to that of North America.[18] The European portion accounted for a quarter of the country's area, and was the cultural and economic center. The eastern part in Asia extended to the Pacific Ocean to the east and Afghanistan to the south, and, except some areas in Central Asia, was much less populous. It spanned over 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi) east to west across 11 time zones, and over 7,200 kilometres (4,500 mi) north to south. It had five climate zones: tundra, taiga, steppes, desert, and mountains.

The Soviet Union had the world's longest boundary, like Russia, measuring over 60,000 kilometres (37,000 mi), or 1 1/2 circumferences of the Earth. Two-thirds of it were a coastline. Across the Bering Strait was the United States. The Soviet Union bordered Afghanistan, China, Czechoslovakia, Finland, Hungary, Iran, Mongolia, North Korea, Norway, Poland, Romania, and Turkey from 1945 to 1991.

The Soviet Union's highest mountain was Communism Peak (now Ismoil Somoni Peak) in Tajikistan, at 7,495 metres (24,590 ft). The Soviet Union also included most of the world's largest lake, the Caspian Sea (shared with Iran), and also Lake Baikal, the world's largest freshwater and deepest lake, an internal body of water in Russia.

History

The last Russian Tsar, Nicholas II, ruled the Russian Empire until his abdication in March 1917 in the aftermath of the February Revolution, due in part to the strain of fighting in World War I, which lacked public support. A short-lived Russian Provisional Government took power, to be overthrown in the October Revolution (N.S. 7 November 1917) by revolutionaries led by the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin.[19]

The Soviet Union was officially established in December 1922 with the union of the Russian, Ukrainian, Byelorussian, and Transcaucasian Soviet republics, each ruled by local Bolshevik parties. Despite the foundation of the Soviet state as a federative entity of many constituent republics, each with its own political and administrative entities, the term "Soviet Russia" – strictly applicable only to the Russian Federative Socialist Republic – was often applied to the entire country by non-Soviet writers and politicians.

Revolution and foundation

Modern revolutionary activity in the Russian Empire began with the Decembrist Revolt of 1825. Although serfdom was abolished in 1861, it was done on terms unfavourable to the peasants and served to encourage revolutionaries. A parliament—the State Duma—was established in 1906 after the Russian Revolution of 1905, but Tsar Nicholas II resisted attempts to move from absolute to constitutional monarchy. Social unrest continued and was aggravated during World War I by military defeat and food shortages in major Soviet cities.

.jpg)

A spontaneous popular uprising in Petrograd, in response to the wartime decay of Russia's economy and morale, culminated in the February Revolution and the toppling of the imperial government in March 1917. The tsarist autocracy was replaced by the Russian Provisional Government, which intended to conduct elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly and to continue fighting on the side of the Entente in World War I.

At the same time, workers' councils, known in Russian as "Soviets", sprang up across the country. The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, pushed for socialist revolution in the Soviets and on the streets. On 7 November 1917, the Red Guards stormed the Winter Palace in Petrograd, ending the rule of the Provisional Government and leaving all political power to the Soviets. This event would later be known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. In December, the Bolsheviks signed an armistice with the Central Powers, though by February 1918, fighting had resumed. In March, the Soviets ended involvement in the war for good and signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

A long and bloody Civil War ensued between the Reds and the Whites, starting in 1917 and ending in 1923 with the Reds' victory. It included foreign intervention, the execution of the former tsar and his family, and the famine of 1921, which killed about five million.[20] In March 1921, during a related conflict with Poland, the Peace of Riga was signed, splitting disputed territories in Belarus and Ukraine between the Republic of Poland and Soviet Russia. Soviet Russia had to resolve similar conflicts with the newly established Republic of Finland, the Republic of Estonia, the Republic of Latvia, and the Republic of Lithuania.

Unification of republics

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

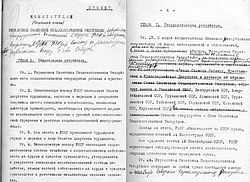

On 28 December 1922, a conference of plenipotentiary delegations from the Russian SFSR, the Transcaucasian SFSR, the Ukrainian SSR and the Byelorussian SSR approved the Treaty of Creation of the USSR[21] and the Declaration of the Creation of the USSR, forming the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.[22] These two documents were confirmed by the 1st Congress of Soviets of the USSR and signed by the heads of the delegations,[23] Mikhail Kalinin, Mikhail Tskhakaya, Mikhail Frunze, Grigory Petrovsky, and Aleksandr Chervyakov,[24] on 30 December 1922. The formal proclamation was made from the stage of the Bolshoi Theatre.

On 1 February 1924, the USSR was recognized by the British Empire. The same year, a Soviet Constitution was approved, legitimizing the December 1922 union.

An intensive restructuring of the economy, industry and politics of the country began in the early days of Soviet power in 1917. A large part of this was done according to the Bolshevik Initial Decrees, government documents signed by Vladimir Lenin. One of the most prominent breakthroughs was the GOELRO plan, which envisioned a major restructuring of the Soviet economy based on total electrification of the country. The plan was developed in 1920 and covered a 10 to 15-year period. It included construction of a network of 30 regional power plants, including ten large hydroelectric power plants, and numerous electric-powered large industrial enterprises.[25] The plan became the prototype for subsequent Five-Year Plans and was fulfilled by 1931.[26]

Stalin era

From its creation, the government in the Soviet Union was based on the one-party rule of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks).[27] After the economic policy of "War Communism" during the Russian Civil War, as a prelude to fully developing socialism in the country, the Soviet government permitted some private enterprise to coexist alongside nationalized industry in the 1920s and total food requisition in the countryside was replaced by a food tax (see New Economic Policy).

The stated purpose of the one-party state was to ensure that capitalist exploitation would not return to the Soviet Union and that the principles of Democratic Centralism would be most effective in representing the people's will in a practical manner. Debate over the future of the economy provided the background for a power struggle in the years after Lenin's death in 1924. Initially, Lenin was to be replaced by a "troika" consisting of Grigory Zinoviev of Ukraine, Lev Kamenev of Moscow, and Joseph Stalin of Georgia.

On 3 April 1922, Stalin was named the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Lenin had appointed Stalin the head of the Workers' and Peasants' Inspectorate, which gave Stalin considerable power. By gradually consolidating his influence and isolating and outmaneuvering his rivals within the party, Stalin became the undisputed leader of the Soviet Union and, by the end of the 1920s, established totalitarian rule. In October 1927, Grigory Zinoviev and Leon Trotsky were expelled from the Central Committee and forced into exile.

In 1928, Stalin introduced the First Five-Year Plan for building a socialist economy. In place of the internationalism expressed by Lenin throughout the Revolution, it aimed to build socialism in one country. In industry, the state assumed control over all existing enterprises and undertook an intensive program of industrialization. In agriculture, rather than adhering to the "lead by example" policy advocated by Lenin,[28] forced collectivisation of farms was implemented all over the country.

Famines ensued, causing millions of deaths; surviving kulaks were persecuted and many sent to Gulags to do forced labour.[29] Social upheaval continued in the mid-1930s. Stalin's Great Purge resulted in the execution or detainment of many "Old Bolsheviks" who had participated in the October Revolution with Lenin. According to declassified Soviet archives, in 1937 and 1938, the NKVD arrested more than one and a half million people, of whom 681,692 were shot. Over those two years that averages to over one thousand executions a day.[30] According to historian Geoffrey Hosking, "...excess deaths during the 1930s as a whole were in the range of 10–11 million."[31] Yet despite the turmoil of the mid-to-late 1930s, the Soviet Union developed a powerful industrial economy in the years before World War II.

1930s

.jpg)

The early 1930s saw closer cooperation between the West and the USSR. From 1932 to 1934, the Soviet Union participated in the World Disarmament Conference. In 1933, diplomatic relations between the United States and the USSR were established when in November, the newly elected President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt chose to formally recognize Stalin's Communist government and negotiated a new trade agreement between the two nations.[32] In September 1934, the Soviet Union joined the League of Nations. After the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, the USSR actively supported the Republican forces against the Nationalists, who were supported by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.

In December 1936, Stalin unveiled a new Soviet Constitution. The constitution was seen as a personal triumph for Stalin, who on this occasion was described by Pravda as a "genius of the new world, the wisest man of the epoch, the great leader of communism." By contrast, Western historians and historians from former Soviet occupied countries have viewed the constitution as a meaningless propaganda document.

The late 1930s saw a shift towards the Axis powers. In 1939, almost a year after the United Kingdom and France had concluded the Munich Agreement with Germany, the USSR dealt with the Nazis as well, both militarily and economically during extensive talks. The two countries concluded the German–Soviet Nonaggression Pact and the German–Soviet Commercial Agreement in August 1939. The nonaggression pact made possible Soviet occupation of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Bessarabia, northern Bukovina, and eastern Poland. In late November of the same year, unable to coerce the Republic of Finland by diplomatic means into moving its border 25 kilometres (16 mi) back from Leningrad, Joseph Stalin ordered the invasion of Finland.

In the east, the Soviet military won several decisive victories during border clashes with the Japanese Empire in 1938 and 1939. However, in April 1941, USSR signed the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact with the Empire of Japan, recognizing the territorial integrity of Manchukuo, a Japanese puppet state.

World War II

Although it has been debated whether the Soviet Union intended to invade Germany once it was strong enough,[33] Germany itself broke the treaty and invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, starting what was known in the USSR as the "Great Patriotic War". The Red Army stopped the seemingly invincible German Army at the Battle of Moscow, aided by an unusually harsh winter. The Battle of Stalingrad, which lasted from late 1942 to early 1943, dealt a severe blow to the Germans from which they never fully recovered and became a turning point in the war. After Stalingrad, Soviet forces drove through Eastern Europe to Berlin before Germany surrendered in 1945. The German Army suffered 80% of its military deaths in the Eastern Front.[34]

The same year, the USSR, in fulfillment of its agreement with the Allies at the Yalta Conference, denounced the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact in April 1945[35] and invaded Manchukuo and other Japan-controlled territories on 9 August 1945.[36] This conflict ended with a decisive Soviet victory, contributing to the unconditional surrender of Japan and the end of World War II.

The Soviet Union suffered greatly in the war, losing around 27 million people.[37] Despite this, it emerged as a superpower in the post-war period. Once denied diplomatic recognition by the Western world, the Soviet Union had official relations with practically every nation by the late 1940s. A member of the United Nations at its foundation in 1945, the Soviet Union became one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, which gave it the right to veto any of its resolutions (see Soviet Union and the United Nations).

The Soviet Union maintained its status as one of the world's two superpowers for four decades through its hegemony in Eastern Europe, military strength, economic strength, aid to developing countries, and scientific research, especially in space technology and weaponry.

Cold War

During the immediate postwar period, the Soviet Union rebuilt and expanded its economy, while maintaining its strictly centralized control. It aided post-war reconstruction in the countries of Eastern Europe, while turning them into satellite states, binding them in a military alliance (the Warsaw Pact) in 1955, and an economic organization (The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance or Comecon) from 1949 to 1991, the latter a counterpart to the European Economic Community.[38] Later, the Comecon supplied aid to the eventually victorious Chinese Communist Party, and saw its influence grow elsewhere in the world. Fearing its ambitions, the Soviet Union's wartime allies, the United Kingdom and the United States, became its enemies. In the ensuing Cold War, the two sides clashed indirectly using mostly proxies.

Khrushchev era

Stalin died on 5 March 1953. Without a mutually agreeable successor, the highest Communist Party officials opted to rule the Soviet Union jointly. Nikita Khrushchev, who had won the power struggle by the mid-1950s, denounced Stalin's use of repression in 1956 and eased repressive controls over party and society. This was known as de-Stalinization.

Moscow considered Eastern Europe to be a buffer zone for the forward defense of its western borders, and ensured its control of the region by transforming the Eastern European countries into satellite states. Soviet military force was used to suppress anti-Stalinist uprisings in Hungary and Poland in 1956.

In the late 1950s, a confrontation with China regarding the USSR's rapprochement with the West and what Mao Zedong perceived as Khrushchev's revisionism led to the Sino–Soviet split. This resulted in a break throughout the global Marxist–Leninist movement, with the governments in Albania, Cambodia and Somalia choosing to ally with China in place of the USSR.

During this period of the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Soviet Union continued to realize scientific and technological exploits in the space race, rivaling the United States: launching the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1 in 1957; a living dog named Laika in 1957; the first human being, Yuri Gagarin in 1961; the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova in 1963; Alexey Leonov, the first person to walk in space in 1965; the first soft landing on the moon by spacecraft Luna 9 in 1966 and the first moon rovers, Lunokhod 1 and Lunokhod 2.[39]

Khrushchev initiated "The Thaw" (better known as Khrushchev's Thaw), a complex shift in political, cultural and economic life in the Soviet Union. This included some openness and contact with other nations and new social and economic policies with more emphasis on commodity goods, allowing living standards to rise dramatically while maintaining high levels of economic growth. Censorship was relaxed as well.

Khrushchev's reforms in agriculture and administration, however, were generally unproductive. In 1962, he precipitated a crisis with the United States over the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. An agreement was made between the Soviet Union and the United States to remove enemy nuclear missiles from both Cuba and Turkey, concluding the crisis. This event caused Khrushchev much embarrassment and loss of prestige, resulting in his removal from power in 1964.

Brezhnev era

Following the ousting of Khrushchev, another period of collective leadership ensued, consisting of Leonid Brezhnev as General Secretary, Alexei Kosygin as Premier and Nikolai Podgorny as Chairman of the Presidium, lasting until Brezhnev established himself in the early 1970s as the preeminent Soviet leader. In 1968, the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact allies invaded Czechoslovakia to halt the Prague Spring reforms.

Brezhnev presided over a period of détente with the West (see SALT I, SALT II, Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty) while at the same time building up Soviet military might.

In October 1977, the third Soviet Constitution was unanimously adopted. The prevailing mood of the Soviet leadership at the time of Brezhnev's death in 1982 was one of aversion to change. The long period of Brezhnev's rule had come to be dubbed one of "standstill", with an aging and ossified top political leadership.

Gorbachev era

Two developments dominated the decade that followed: the increasingly apparent crumbling of the Soviet Union's economic and political structures, and the patchwork attempts at reforms to reverse that process. Kenneth S. Deffeyes argued in Beyond Oil that the Reagan administration encouraged Saudi Arabia to lower the price of oil to the point where the Soviets could not make a profit selling their oil, so that the USSR's hard currency reserves became depleted.[40]

Brezhnev's next two successors, transitional figures with deep roots in his tradition, did not last long. Yuri Andropov was 68 years old and Konstantin Chernenko 72 when they assumed power; both died in less than two years. In an attempt to avoid a third short-lived leader, in 1985, the Soviets turned to the next generation and selected Mikhail Gorbachev.

Gorbachev made significant changes in the economy and party leadership, called perestroika. His policy of glasnost freed public access to information after decades of heavy government censorship.

Gorbachev also moved to end the Cold War. In 1988, the Soviet Union abandoned its nine-year war in Afghanistan and began to withdraw its forces. In the late 1980s, he refused military support to the Soviet Union's former satellite states, which favored the Revolutions of 1989. With the tearing down of the Berlin Wall and with East Germany and West Germany pursuing unification, the Iron Curtain came down.

In the late 1980s, the constituent republics of the Soviet Union started legal moves towards potentially declaring sovereignty over their territories, citing Article 72 of the USSR constitution, which stated that any constituent republic was free to secede.[41] On 7 April 1990, a law was passed allowing a republic to secede if more than two-thirds of its residents voted for it in a referendum.[42] Many held their first free elections in the Soviet era for their own national legislatures in 1990. Many of these legislatures proceeded to produce legislation contradicting the Union laws in what was known as the "War of Laws".

In 1989, the Russian SFSR, which was then the largest constituent republic (with about half of the population) convened a newly elected Congress of People's Deputies. Boris Yeltsin was elected its chairman. On 12 June 1990, the Congress declared Russia's sovereignty over its territory and proceeded to pass laws that attempted to supersede some of the USSR's laws. After a landslide victory of Sąjūdis in Lithuania, that country declared its independence restored on 11 March 1990.

A referendum for the preservation of the USSR was held on 17 March 1991 in nine republics (the remainder having boycotted the vote), with the majority of the population in those nine republics voting for preservation of the Union. The referendum gave Gorbachev a minor boost. In the summer of 1991, the New Union Treaty, which would have turned the Soviet Union into a much looser Union, was agreed upon by eight republics.

The signing of the treaty, however, was interrupted by the August Coup—an attempted coup d'état by hardline members of the government and the KGB who sought to reverse Gorbachev's reforms and reassert the central government's control over the republics. After the coup collapsed, Yeltsin was seen as a hero for his decisive actions, while Gorbachev's power was effectively ended. The balance of power tipped significantly towards the republics. In August 1991, Latvia and Estonia immediately declared the restoration of their full independence (following Lithuania's 1990 example). Gorbachev resigned as general secretary in late August, and soon afterward the Party's activities were indefinitely suspended—effectively ending its rule. By the fall, Gorbachev could no longer influence events outside of Moscow, and he was being challenged even there by Yeltsin, who had been elected President of Russia in July 1991.

Dissolution

The remaining 12 republics continued discussing new, increasingly looser, models of the Union. However, by December, all except Russia and Kazakhstan had formally declared independence. During this time, Yeltsin took over what remained of the Soviet government, including the Kremlin. The final blow was struck on 1 December, when Ukraine, the second most powerful republic, voted overwhelmingly for independence. Ukraine's secession ended any realistic chance of the Soviet Union staying together even on a limited scale.

On 8 December 1991, the presidents of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus (formerly Byelorussia), signed the Belavezha Accords, which declared the Soviet Union dissolved and established the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in its place. While doubts remained over the authority of the accords to do this, on 21 December 1991, the representatives of all Soviet republics except Georgia signed the Alma-Ata Protocol, which confirmed the accords. On 25 December 1991, Gorbachev resigned as the President of the USSR, declaring the office extinct. He turned the powers that had been vested in the presidency over to Yeltsin. That night, the Soviet flag was lowered for the last time, and the Russian tricolor was raised in its place.

The following day, the Supreme Soviet, the highest governmental body of the Soviet Union, voted both itself and the Soviet Union out of existence. This is generally recognized as marking the official, final dissolution of the Soviet Union as a functioning state. The Soviet Army originally remained under overall CIS command, but was soon absorbed into the different military forces of the newly independent states. The few remaining Soviet institutions that had not been taken over by Russia ceased to function by the end of 1991.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union on 26 December 1991, Russia was internationally recognized[43] as its legal successor on the international stage. To that end, Russia voluntarily accepted all Soviet foreign debt and claimed overseas Soviet properties as its own. Under the 1992 Lisbon Protocol, Russia also agreed to receive all nuclear weapons remaining in the territory of other former Soviet republics. Since then, the Russian Federation has assumed the Soviet Union's rights and obligations.

Post-Soviet states

The analysis of the succession of states with respect to the 15 post-Soviet states is complex. The Russian Federation is seen as the legal continuator state and is for most purposes the heir to the Soviet Union. It retained ownership of all former Soviet embassy properties, as well as the old Soviet UN membership and permanent membership on the Security Council.[44] The Baltic states are not successor states to the Soviet Union;[45] they are instead considered to have de jure continuity with their pre-World War II governments through the non-recognition of the original Soviet incorporation in 1940.[44] The other 11 post-Soviet states are considered newly-independent successor states to the Soviet Union.[44]

There are additionally four states that claim independence from the other internationally recognized post-Soviet states, but possess limited international recognition: Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, South Ossetia, and Transnistria. The Chechen separatist movement of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria lacks any international recognition.

Politics

There were three power hierarchies in the Soviet Union: the legislative branch represented by the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the government represented by the Council of Ministers, and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the only legal party and the ultimate policymaker in the country.[46]

Communist Party

At the top of the Communist Party was the Central Committee, elected at Party Congresses and Conferences. The Central Committee in turn voted for a Politburo (called the Presidium between 1952–1966), Secretariat and the General Secretary (First Secretary from 1953 to 1966), the de facto highest office in the USSR.[47] Depending on the degree of power consolidation, it was either the Politburo as a collective body or the General Secretary, who always was one of the Politburo members, that effectively led the party and the country[48] (except for the period of the highly personalized authority of Stalin, exercised directly through his position in the Council of Ministers rather than the Politburo after 1941).[49] They were not controlled by the general party membership, as the key principle of the party organization was democratic centralism, demanding strict subordination to higher bodies, and elections went uncontested, endorsing the candidates proposed from above.[50]

The Communist Party maintained its dominance over the state largely through its control over the system of appointments. All senior government officials and most deputies of the Supreme Soviet were members of the CPSU. Of the party heads themselves, Stalin in 1941–1953 and Khrushchev in 1958–1964 were Premiers. Upon the forced retirement of Khrushchev, the party leader was prohibited from this kind of double membership,[51] but the later General Secretaries for at least some part of their tenure occupied the largely ceremonial position of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, the nominal head of state. The institutions at lower levels were overseen and at times supplanted by primary party organizations.[52]

In practice, however, the degree of control the party was able to exercise over the state bureaucracy, particularly after the death of Stalin, was far from total, with the bureaucracy pursuing different interests that were at times in conflict with the party.[53] Nor was the party itself monolithic from top to bottom, although factions were officially banned.[54]

Government

The Supreme Soviet (successor of the Congress of Soviets and Central Executive Committee) was nominally the highest state body for most of the Soviet history,[55] at first acting as a rubber stamp institution, approving and implementing all decisions made by the party. However, the powers and functions of the Supreme Soviet were extended in the late 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, including the creation of new state commissions and committees. It gained additional powers when it came to the approval of the Five-Year Plans and the Soviet state budget.[56] The Supreme Soviet elected a Presidium to wield its power between plenary sessions,[57] ordinarily held twice a year, and appointed the Supreme Court,[58] the Procurator General[59] and the Council of Ministers (known before 1946 as the Council of People's Commissars), headed by the Chairman (Premier) and managing an enormous bureaucracy responsible for the administration of the economy and society.[57] State and party structures of the constituent republics largely emulated the structure of the central institutions, although the Russian SFSR, unlike the other constituent republics, for most of its history had no republican branch of the CPSU, being ruled directly by the union-wide party until 1990. Local authorities were organized likewise into party committees, local Soviets and executive committees. While the state system was nominally federal, the party was unitary.[60]

The state security police (the KGB and its predecessor agencies) played an important role in Soviet politics. It was instrumental in the Stalinist terror,[61] but after the death of Stalin, the state security police was brought under strict party control. Under Yuri Andropov, KGB chairman in 1967–1982 and General Secretary from 1982 to 1983, the KGB engaged in the suppression of political dissent and maintained an extensive network of informers, reasserting itself as a political actor to some extent independent of the party-state structure,[62] culminating in the anti-corruption campaign targeting high party officials in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[63]

Separation of power and reform

The Union constitutions, which were promulgated in 1918, 1924, 1936 and 1977,[64] did not limit state power. No formal separation of powers existed between the Party, Supreme Soviet and Council of Ministers[65] that represented executive and legislative branches of the government. The system was governed less by statute than by informal conventions, and no settled mechanism of leadership succession existed. Bitter and at times deadly power struggles took place in the Politburo after the deaths of Lenin[66] and Joseph Stalin,[67] as well as after Khrushchev's dismissal,[68] itself due to a decision by both the Politburo and the Central Committee.[69] All leaders of the Communist Party before Gorbachev died in office, except Georgy Malenkov[70] and Khrushchev, both dismissed from the party leadership amid internal struggle within the party.[69]

Between 1988 and 1990, facing considerable opposition, Mikhail Gorbachev enacted reforms shifting power away from the highest bodies of the party and making the Supreme Soviet less dependent on them. The Congress of People's Deputies was established, the majority of whose members were directly elected in competitive elections held in March 1989. The Congress now elected the Supreme Soviet, which became a full-time parliament, much stronger than before. For the first time since the 1920s, it refused to rubber stamp proposals from the party and Council of Ministers.[71] In 1990, Gorbachev introduced and assumed the position of the President of the Soviet Union, concentrated power in his executive office, independent of the party, and subordinated the government,[72] now renamed the Cabinet of Ministers of the USSR, to himself.[73]

Tensions grew between the union-wide authorities under Gorbachev, reformists led in Russia by Boris Yeltsin and controlling the newly elected Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR, and Communist Party hardliners. On 19–21 August 1991, a group of hardliners staged an abortive coup attempt. Following the failed coup, the State Council of the Soviet Union became the highest organ of state power "in the period of transition".[74] Gorbachev resigned as General Secretary, only remaining President for the final months of the existence of the USSR.[75]

Judicial system

The judiciary was not independent of the other branches of government. The Supreme Court supervised the lower courts (People's Court) and applied the law as established by the Constitution or as interpreted by the Supreme Soviet. The Constitutional Oversight Committee reviewed the constitutionality of laws and acts. The Soviet Union used the inquisitorial system of Roman law, where the judge, procurator, and defense attorney collaborate to establish the truth.[76]

Administrative divisions

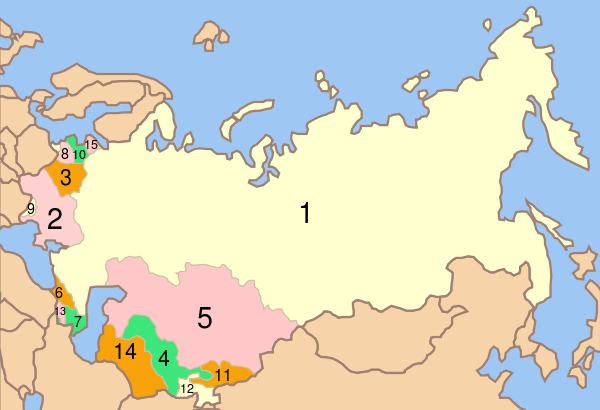

Constitutionally, the USSR was a federation of constituent Union Republics, which were either unitary states, such as Ukraine or Belarus (SSRs), or federal states, such as Russia or Transcaucasia (SFSRs),[46] all four being the founding republics who signed the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR in December 1922. In 1924, during the national delimitation in Central Asia, the Uzbek and Turkmen SSRs were formed from parts of the Russia's Turkestan ASSR and two Soviet dependencies, the Khorezm and Bukharan SSRs. In 1929, the Tajik SSR was split off from the Uzbek SSR. With the constitution of 1936, the Transcaucasian SFSR was dissolved, resulting in its constituent Georgian, Armenian and Azerbaijan SSRs being elevated to Union Republics, while the Kazakh and Kirghiz SSRs were split off from Russian SFSR, resulting in the same status.[77] In August 1940, the Moldavian SSR was formed from parts of the Ukrainian SSR and Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. The Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian SSRs were also admitted into the union. The Karelo-Finnish SSR was split off from Russia as a Union Republic in March 1940 and was reabsorbed in 1956. Between July 1956 and September 1991, there were 15 union republics (see map below).[78] The RSFSR was by far the largest republic, in both population and geography, as well as the strongest and most developed economically due to its vast natural resources. Additionally, it was the most powerful politically; Russians dominated the state and party apparatuses, and all but one undisputed leader of the Soviet Union was a Russian (the only one who wasn't, Stalin, was a Russified Georgian). For these reasons, until the 1980s the Soviet Union was commonly—but incorrectly—referred to as "Russia."

| # | Republic | Map of the Union Republics between 1956–1991 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | |

|

| 2 | | |

| 3 | | |

| 4 | | |

| 5 | | |

| 6 | | |

| 7 | | |

| 8 | | |

| 9 | | |

| 10 | | |

| 11 | | |

| 12 | | |

| 13 | | |

| 14 | | |

| 15 | |

Economy

The Soviet Union became the first country to adopt a planned economy, whereby production and distribution of goods were centralised and directed by the government. The first Bolshevik experience with a command economy was the policy of War Communism, which involved the nationalization of industry, centralized distribution of output, coercive requisition of agricultural production, and attempts to eliminate the circulation of money, as well as private enterprises and free trade. After the severe economic collapse caused by the war, Lenin replaced War Communism with the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921, legalising free trade and private ownership of smaller businesses. The economy quickly recovered.[79]

Following a lengthy debate among the members of Politburo over the course of economic development, by 1928–1929, upon gaining control of the country, Joseph Stalin abandoned the NEP and pushed for full central planning, starting forced collectivisation of agriculture and enacting draconian labor legislation. Resources were mobilised for rapid industrialisation, which greatly expanded Soviet capacity in heavy industry and capital goods during the 1930s.[79] Preparation for war was one of the main driving forces behind industrialisation, mostly due to distrust of the outside capitalistic world.[80] As a result, the USSR was transformed from a largely agrarian economy into a great industrial power, leading the way for its emergence as a superpower after World War II.[81] During the war, the Soviet economy and infrastructure suffered massive devastation and required extensive reconstruction.[82]

By the early 1940s, the Soviet economy had become relatively self-sufficient; for most of the period until the creation of Comecon, only a very small share of domestic products was traded internationally.[83] After the creation of the Eastern Bloc, external trade rose rapidly. Still the influence of the world economy on the USSR was limited by fixed domestic prices and a state monopoly on foreign trade.[84] Grain and sophisticated consumer manufactures became major import articles from around the 1960s.[83] During the arms race of the Cold War, the Soviet economy was burdened by military expenditures, heavily lobbied for by a powerful bureaucracy dependent on the arms industry. At the same time, the Soviet Union became the largest arms exporter to the Third World. Significant amounts of Soviet resources during the Cold War were allocated in aid to the other socialist states.[83]

From the 1930s until its collapse in the late 1980s, the way the Soviet economy operated remained essentially unchanged. The economy was formally directed by central planning, carried out by Gosplan and organized in five-year plans. In practice, however, the plans were highly aggregated and provisional, subject to ad hoc intervention by superiors. All key economic decisions were taken by the political leadership. Allocated resources and plan targets were normally denominated in rubles rather than in physical goods. Credit was discouraged, but widespread. Final allocation of output was achieved through relatively decentralized, unplanned contracting. Although in theory prices were legally set from above, in practice the actual prices were often negotiated, and informal horizontal links (between producer factories etc.) were widespread.[79]

A number of basic services were state-funded, such as education and healthcare. In the manufacturing sector, heavy industry and defense were assigned higher priority than the production of consumer goods.[85] Consumer goods, particularly outside large cities, were often scarce, of poor quality and limited choice. Under command economy, consumers had almost no influence over production, so the changing demands of a population with growing incomes could not be satisfied by supplies at rigidly fixed prices.[86] A massive unplanned second economy grew up alongside the planned one at low levels, providing some of the goods and services that the planners could not. Legalisation of some elements of the decentralised economy was attempted with the reform of 1965.[79]

Although statistics of the Soviet economy are notoriously unreliable and its economic growth difficult to estimate precisely,[87][88] by most accounts, the economy continued to expand until the mid-1980s. During the 1950s and 1960s, the Soviet economy experienced comparatively high growth and was catching up to the West.[89] However, after 1970, the growth, while still positive, steadily declined much more quickly and consistently than in other countries despite a rapid increase in the capital stock (the rate of increase in capital was only surpassed by Japan).[79]

Overall, between 1960 and 1989, the growth rate of per capita income in the Soviet Union was slightly above the world average (based on 102 countries). According to Stanley Fischer and William Easterly, growth could have been faster. By their calculation, per capita income of Soviet Union in 1989 should have been twice as high as it was considering the amount of investment, education and population. The authors attribute this poor performance to low productivity of capital in the Soviet Union.[90] Steven Rosenfielde states that the standard of living actually declined as a result of Stalin's despotism, and while there was a brief improvement following his death, lapsed into stagnation.[91]

In 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev tried to reform and revitalize the economy with his program of perestroika. His policies relaxed state control over enterprises, but did not yet allow it to be replaced by market incentives, ultimately resulting in a sharp decline in production output. The economy, already suffering from reduced petroleum export revenues, started to collapse. Prices were still fixed, and property was still largely state-owned until after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[79][86] For most of the period after World War II up to its collapse, the Soviet economy was the second largest in the world by GDP (PPP), and was 3rd in the world during the middle of the 1980s to 1989,[92] though in per capita terms the Soviet GDP was behind that of the First World countries.[93]

Energy

The need for fuel declined in the Soviet Union from the 1970s to the 1980s,[94] both per ruble of gross social product and per ruble of industrial product. At the start, this decline grew very rapidly but gradually slowed down between 1970 and 1975. From 1975 and 1980, it grew even slower, only 2.6 percent.[95] David Wilson, a historian, believed that the gas industry would account for 40 percent of Soviet fuel production by the end of the century. His theory did not come to fruition because of the USSR's collapse.[96] The USSR, in theory, would have continued to have an economic growth rate of 2–2.5 percent during the 1990s because of Soviet energy fields.[97] However, the energy sector faced many difficulties, among them the country's high military expenditure and hostile relations with the First World (pre-Gorbachev era).[98]

In 1991, the Soviet Union had a pipeline network of 82,000 kilometres (51,000 mi) for crude oil and another 206,500 kilometres (128,300 mi) for natural gas.[99] Petroleum and petroleum-based products, natural gas, metals, wood, agricultural products, and a variety of manufactured goods, primarily machinery, arms and military equipment, were exported.[100] In the 1970s and 1980s, the Soviet Union heavily relied on fossil fuel exports to earn hard currency.[83] At its peak in 1988, it was the largest producer and second largest exporter of crude oil, surpassed only by Saudi Arabia.[101]

Science and technology

The Soviet Union placed great emphasis on science and technology within its economy,[102] however, the most remarkable Soviet successes in technology, such as producing the world's first space satellite, typically were the responsibility of the military.[85] Lenin believed that the USSR would never overtake the developed world if it remained as technologically backward as it was upon its founding. Soviet authorities proved their commitment to Lenin's belief by developing massive networks, research and development organizations. In the early 1960s, the Soviets awarded 40% of chemistry PhD's to women, compared to only 5% who received such a degree in the United States.[103] By 1989, Soviet scientists were among the world's best-trained specialists in several areas, such as energy physics, selected areas of medicine, mathematics, welding and military technologies. Due to rigid state planning and bureaucracy, the Soviets remained far behind technologically in chemistry, biology, and computers when compared to the First World.

Project Socrates, under the Reagan administration, determined that the Soviet Union addressed the acquisition of science and technology in a manner that was radically different from what the US was using. In the case of the US, economic prioritization was being used for indigenous research and development as the means to acquire science and technology in both the private and public sectors. In contrast, the Soviet Union was offensively and defensively maneuvering in the acquisition and utilization of the worldwide technology, to increase the competitive advantage that they acquired from the technology, while preventing the US from acquiring a competitive advantage. However, in addition, the Soviet Union's technology-based planning was executed in a centralized, government-centric manner that greatly hindered its flexibility. It was this significant lack of flexibility that was exploited by the US to undermine the strength of the Soviet Union and thus foster its reform.[104][105][106]

Transport

Transport was a key component of the nation's economy. The economic centralization of the late 1920s and 1930s led to the development of infrastructure on a massive scale, most notably the establishment of Aeroflot, an aviation enterprise.[107] The country had a wide variety of modes of transport by land, water and air.[99] However, due to bad maintenance, much of the road, water and Soviet civil aviation transport were outdated and technologically backward compared to the First World.[108]

Soviet rail transport was the largest and most intensively used in the world;[108] it was also better developed than most of its Western counterparts.[109] By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Soviet economists were calling for the construction of more roads to alleviate some of the burden from the railways and to improve the Soviet state budget.[110] The road network and automobile industry[111] remained underdeveloped,[112] and dirt roads were common outside major cities.[113] Soviet maintenance projects proved unable to take care of even the few roads the country had. By the early-to-mid-1980s, the Soviet authorities tried to solve the road problem by ordering the construction of new ones.[113] Meanwhile, the automobile industry was growing at a faster rate than road construction.[114] The underdeveloped road network led to a growing demand for public transport.[115]

Despite improvements, several aspects of the transport sector were still riddled with problems due to outdated infrastructure, lack of investment, corruption and bad decision-making. Soviet authorities were unable to meet the growing demand for transport infrastructure and services.

The Soviet merchant fleet was one of the largest in the world.[99]

Demographics

Excess deaths over the course of World War I and the Russian Civil War (including the postwar famine) amounted to a combined total of 18 million,[116] some 10 million in the 1930s,[31] and more than 26 million in 1941–5. The postwar Soviet population was 45 to 50 million smaller than it would have been if pre-war demographic growth had continued.[37] According to Catherine Merridale, "... reasonable estimate would place the total number of excess deaths for the whole period somewhere around 60 million."[117]

The crude birth rate of the USSR decreased from 44.0 per thousand in 1926 to 18.0 in 1974, largely due to increasing urbanization and the rising average age of marriages. The crude death rate demonstrated a gradual decrease as well – from 23.7 per thousand in 1926 to 8.7 in 1974. In general, the birth rates of the southern republics in Transcaucasia and Central Asia were considerably higher than those in the northern parts of the Soviet Union, and in some cases even increased in the post–World War II period, a phenomenon partly attributed to slower rates of urbanization and traditionally earlier marriages in the southern republics.[118] Soviet Europe moved towards sub-replacement fertility, while Soviet Central Asia continued to exhibit population growth well above replacement-level fertility.[119]

The late 1960s and the 1970s witnessed a reversal of the declining trajectory of the rate of mortality in the USSR, and was especially notable among men of working age, but was also prevalent in Russia and other predominantly Slavic areas of the country.[120] An analysis of the official data from the late 1980s showed that after worsening in the late-1970s and the early 1980s, adult mortality began to improve again.[121] The infant mortality rate increased from 24.7 in 1970 to 27.9 in 1974. Some researchers regarded the rise as largely real, a consequence of worsening health conditions and services.[122] The rises in both adult and infant mortality were not explained or defended by Soviet officials, and the Soviet government simply stopped publishing all mortality statistics for ten years. Soviet demographers and health specialists remained silent about the mortality increases until the late-1980s, when the publication of mortality data resumed and researchers could delve into the real causes.[123]

Education

Before 1917, education was not free in the Russian Empire and was therefore either inaccessible or barely accessible for many children from lower-class working and peasant families. Estimates from 1917 recorded that 75–85 percent of the Russian population was illiterate.

Anatoly Lunacharsky became the first People's Commissar for Education of Soviet Russia. At the beginning, the Soviet authorities placed great emphasis on the elimination of illiteracy. People who were literate were automatically hired as teachers. For a short period, quality was sacrificed for quantity. By 1940, Joseph Stalin could announce that illiteracy had been eliminated. Throughout the 1930s social mobility rose sharply, which has been attributed to Soviet reforms in education.[124] In the aftermath of the Great Patriotic War, the country's educational system expanded dramatically. This expansion had a tremendous effect. In the 1960s, nearly all Soviet children had access to education, the only exception being those living in remote areas. Nikita Khrushchev tried to make education more accessible, making it clear to children that education was closely linked to the needs of society. Education also became important in giving rise to the New Man.[125]

The country's system of education was highly centralized and universally accessible to all citizens, with affirmative action for applicants from nations associated with cultural backwardness. Citizens directly entering the work force had the constitutional right to a job and to free vocational training. The Brezhnev administration introduced a rule that required all university applicants to present a reference from the local Komsomol party secretary.[126] According to statistics from 1986, the number of higher education students per the population of 10,000 was 181 for the USSR, compared to 517 for the U.S.[127]

Ethnic groups

The Soviet Union was a very ethnically diverse country, with more than 100 distinct ethnic groups. The total population was estimated at 293 million in 1991. According to a 1990 estimate, the majority were Russians (50.78%), followed by Ukrainians (15.45%) and Uzbeks (5.84%).[128]

All citizens of the USSR had their own ethnic affiliation. The ethnicity of a person was chosen at the age of sixteen[129] by the child's parents. If the parents did not agree, the child was automatically assigned the ethnicity of the father. Partly due to Soviet policies, some of the smaller minority ethnic groups were considered part of larger ones, such as the Mingrelians of the Georgian SSR, who were classified with the linguistically related Georgians.[130] Some ethnic groups voluntarily assimilated, while others were brought in by force. Russians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians shared close cultural ties, while other groups did not. With multiple nationalities living in the same territory, ethnic antagonisms developed over the years.[131]

-

Ethnographic map of the Soviet Union, 1941

-

Number and share of Ukrainians in the population of the regions of the RSFSR (1926 census)

-

.png)

Map showing the distribution of Muslims within the Soviet Union in 1979

-

Number and share of Ukrainians in the population of the regions of the RSFSR (1979 census)

Health

In 1917, before the revolution, health conditions were significantly behind the developed countries. As Lenin later noted, "Either the lice will defeat socialism, or socialism will defeat the lice".[132] The Soviet principle of health care was conceived by the People's Commissariat for Health in 1918. Health care was to be controlled by the state and would be provided to its citizens free of charge, this at the time being a revolutionary concept. Article 42 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution gave all citizens the right to health protection and free access to any health institutions in the USSR. Before Leonid Brezhnev became head of state, the healthcare system of the Soviet Union was held in high esteem by many foreign specialists. This changed however, from Brezhnev's accession and Mikhail Gorbachev's tenure as leader, the Soviet health care system was heavily criticised for many basic faults, such as the quality of service and the unevenness in its provision.[133] Minister of Health Yevgeniy Chazov, during the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, while highlighting such Soviet successes as having the most doctors and hospitals in the world, recognised the system's areas for improvement and felt that billions of Soviet rubles were squandered.[134]

After the socialist revolution, the life expectancy for all age groups went up. This statistic in itself was seen by some that the socialist system was superior to the capitalist system. These improvements continued into the 1960s, when the life expectancy in the Soviet Union surpassed that of the United States. It remained stable during most years, although in the 1970s, it went down slightly, possibly because of alcohol abuse. At the same time, infant mortality began to rise. After 1974, the government stopped publishing statistics on this. This trend can be partly explained by the number of pregnancies rising drastically in the Asian part of the country where infant mortality was highest, while declining markedly in the more developed European part of the Soviet Union.[135] The USSR had several centers of excellence, such as the Fyodorov Eye Microsurgery Complex, founded in 1988 by Russian eye surgeon Svyatoslav Fyodorov.

Language

The Soviet government headed by Vladimir Lenin gave small language groups their own writing systems.[136] The development of these writing systems was very successful, even though some flaws were detected. During the later days of the USSR, countries with the same multilingual situation implemented similar policies. A serious problem when creating these writing systems was that the languages differed dialectally greatly from each other.[137] When a language had been given a writing system and appeared in a notable publication, that language would attain "official language" status. There were many minority languages which never received their own writing system; therefore their speakers were forced to have a second language.[138] There are examples where the Soviet government retreated from this policy, most notable under Stalin's regime, where education was discontinued in languages which were not widespread enough. These languages were then assimilated into another language, mostly Russian.[139] During the Great Patriotic War (World War II), some minority languages were banned, and their speakers accused of collaborating with the enemy.[140]

As the most widely spoken of the Soviet Union's many languages, Russian de facto functioned as an official language, as the "language of interethnic communication" (Russian: язык межнационального общения), but only assumed the de jure status as the official national language in 1990.[141]

Religion

The religious made up a significant minority of the Soviet Union prior to break up. In 1990, the religious makeup was 20% Russian Orthodox, 10% Muslim, 7% Protestant, Georgian Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox, and Roman Catholic, less than 1% Jewish and 60% atheist.[142]

Christianity and Islam had the greatest number of adherents among the Soviet state's religious citizens.[143] Eastern Christianity predominated among Christians, with Russia's traditional Russian Orthodox Church being the Soviet Union's largest Christian denomination. About 90 percent of the Soviet Union's Muslims were Sunnis, with Shiites concentrated in the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic.[143] Smaller groups included Roman Catholics, Jews, Buddhists, and a variety of Protestant sects.[143]

Religious influence had been strong in the Russian Empire. The Russian Orthodox Church enjoyed a privileged status as the church of the monarchy and took part in carrying out official state functions.[144] The immediate period following the establishment of the Soviet state included a struggle against the Orthodox Church, which the revolutionaries considered an ally of the former ruling classes.[145]

In Soviet law, the "freedom to hold religious services" was constitutionally guaranteed, although the ruling Communist Party regarded religion as incompatible with the Marxist spirit of scientific materialism.[145] In practice, the Soviet system subscribed to a narrow interpretation of this right, and in fact utilized a range of official measures to discourage religion and curb the activities of religious groups.[145]

The 1918 Council of People's Commissars decree establishing the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) as a secular state also decreed that "the teaching of religion in all [places] where subjects of general instruction are taught, is forbidden. Citizens may teach and may be taught religion privately."[146] Among further restrictions, those adopted in 1929, a half-decade into Stalin's rule, included express prohibitions on a range of church activities, including meetings for organized Bible study.[145] Both Christian and non-Christian establishments were shut down by the thousands in the 1920s and 1930s. By 1940, as many as 90 percent of the churches, synagogues, and mosques that had been operating in 1917 were closed.[147]

Convinced that religious anti-Sovietism had become a thing of the past, the Stalin regime began shifting to a more moderate religion policy in the late 1930s.[148] Soviet religious establishments overwhelmingly rallied to support the war effort during the Soviet war with Nazi Germany. Amid other accommodations to religious faith, churches were reopened, Radio Moscow began broadcasting a religious hour, and a historic meeting between Stalin and Orthodox Church leader Patriarch Sergius I of Moscow was held in 1943.[148] The general tendency of this period was an increase in religious activity among believers of all faiths.[149] The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in the USSR was persecuted.

The Soviet establishment again clashed with the churches under General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev's leadership in 1958–1964, a period when atheism was emphasized in the educational curriculum, and numerous state publications promoted atheistic views.[148] During this period, the number of churches fell from 20,000 to 10,000 from 1959 to 1965, and the number of synagogues dropped from 500 to 97.[150] The number of working mosques also declined, falling from 1,500 to 500 within a decade.[150]

Religious institutions remained monitored by the Soviet government, but churches, synagogues, temples, and mosques were all given more leeway in the Brezhnev era.[151] Official relations between the Orthodox Church and the Soviet government again warmed to the point that the Brezhnev government twice honored Orthodox Patriarch Alexy I with the Order of the Red Banner of Labour.[152] A poll conducted by Soviet authorities in 1982 recorded 20 percent of the Soviet population as "active religious believers."[153]

Women

Soviet efforts to expand social, political and economic opportunities for women constitute "the earliest and perhaps most far-reaching attempt ever undertaken to transform the status and role of women."[154]

Culture

The culture of the Soviet Union passed through several stages during the USSR's 70-year existence. During the first eleven years following the Revolution (1918–1929), there was relative freedom and artists experimented with several different styles to find a distinctive Soviet style of art. Lenin wanted art to be accessible to the Russian people. On the other hand, hundreds of intellectuals, writers, and artists were exiled or executed, and their work banned, for example Nikolay Gumilev (shot for alleged conspiring against the Bolshevik regime) and Yevgeny Zamyatin (banned).[155]

The government encouraged a variety of trends. In art and literature, numerous schools, some traditional and others radically experimental, proliferated. Communist writers Maksim Gorky and Vladimir Mayakovsky were active during this time. Film, as a means of influencing a largely illiterate society, received encouragement from the state; much of director Sergei Eisenstein's best work dates from this period.

Later, during Stalin's rule, Soviet culture was characterised by the rise and domination of the government-imposed style of socialist realism, with all other trends being severely repressed, with rare exceptions, for example Mikhail Bulgakov's works. Many writers were imprisoned and killed.[156]

Following the Khrushchev Thaw of the late 1950s and early 1960s, censorship was diminished. During this time, a distinctive period of Soviet culture developed characterized by conformist public life and intense focus on personal life. Greater experimentation in art forms were again permissible, with the result that more sophisticated and subtly critical work began to be produced. The regime loosened its emphasis on socialist realism; thus, for instance, many protagonists of the novels of author Yury Trifonov concerned themselves with problems of daily life rather than with building socialism. An underground dissident literature, known as samizdat, developed during this late period. In architecture the Khrushchev era mostly focused on functional design as opposed to the highly decorated style of Stalin's epoch.

In the second half of the 1980s, Gorbachev's policies of perestroika and glasnost significantly expanded freedom of expression in the media and press.[157]

Attempt to challenge the dissolution of the Soviet Union in Court

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Court documents On the recognition of the unconstitutional dissolution of the USSR. |

In 2014, on the initiative of the citizen of the city of Tolyatti, Dmitry Tretyakov, born in 1981, took judicial attempts to challenge the alleged unconstitutional dissolution of the Soviet Union in court. In his claim to the government of Russia, the applicant referred to the legislation of the Soviet Union, Law of the USSR No. 1409-I dated 3 April 1990 "On the order of issues related to the secession of Union republics from the USSR".[158][159]

On 10 January 2014 the Supreme Court of Russia issued a ruling, which refused to consider the claim, stating that "acts do not affect the rights and freedoms or legitimate interests of the applicant". On 8 April, the appellate court upheld the first instance decision.[160][161][162]

On 29 May, the Constitutional Court of Russia with 18 judges, chaired by Valery Zorkin, dismissed the complaint in a final unappealable decision.[163]

On 27 November 2014, the European court of human rights in Strasbourg, under the chairmanship of judge Elisabeth Steiner decided to reject the complaint, additionally stating that the decision cannot be appealed to the Grand chamber.[164]

See also

- Collective Security Treaty Organization

- Commonwealth of Independent States

- Eurasian Economic Union

- Index of Soviet Union-related articles

- Neo-Sovietism

- Soviet Empire

References

- ↑ Declaration № 142-Н of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, formally establishing the dissolution of the Soviet Union as a state and subject of international law. (Russian)

- ↑ Scott Shane (2 October 1990). "73 Years of State Atheism in the Soviet Union, ended amid collapse in 1990". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Historical Dictionary of Socialism. James C. Docherty, Peter Lamb. Page 85. "The Soviet Union was a one-party Marxist-Leninist state.".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ideology, Interests, and Identity. Stephen H. Hanson. Page 14. "the USSR was officially a Marxist-Leninist state"

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 The Fine Line between the Enforcement of Human Rights Agreements and the Violation of National Sovereignty: The Case of Soviet Dissidents. Jennifer Noe Pahre. Page 336. "[...] the Soviet Union, as a Marxist-Leninist state [...]". Page 348. "The Soviet Union is a Marxist–Leninist state."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Leninist National Policy: Solution to the "National Question"?. Walker Connor. Page 31. "[...] four Marxist-Leninist states (the Soviet Union, China, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia)[...]"

- ↑ Declaration № 142-Н of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, formally establishing the dissolution of the Soviet Union as a state and subject of international law. (Russian)

- ↑ Bridget O'Laughlin (1975) Marxist Approaches in Anthropology Annual Review of Anthropology Vol. 4: pp. 341–70 (October 1975) doi:10.1146/annurev.an.04.100175.002013.

William Roseberry (1997) Marx and Anthropology Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 26: pp. 25–46 (October 1997) doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.25 - ↑ Robert Service (9 September 2005). Stalin: a biography. Picador. ISBN 978-0-330-41913-0.

- ↑ Norman Davies: "Since 75%–80% of all German losses were inflicted on the eastern front it follows that the efforts of the Western allies accounted for only 20%–25%". Source: Sunday Times, 5 November 2006.

- ↑ David Holloway (27 March 1996). Stalin and the Bomb. Yale University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-300-06664-7.

- ↑ Turner 1987, p. 23

- ↑ Philip Whyman, Mark Baimbridge and Andrew Mullen (2012). The Political Economy of the European Social Model (Routledge Studies in the European Economy). Routledge. ISBN 0415476291 p. 108 "In short, Gorbachev aimed to lead the Soviet Union towards the Scandinavian social democratic model."

- ↑ Klein, Naomi (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Picador. ISBN 0312427999 p. 276

- ↑ Iain McLean (1996). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285288-5.

- ↑ "Russia is now a party to any Treaties to which the former Soviet Union was a party, and enjoys the same rights and obligations as the former Soviet Union, except insofar as adjustments are necessarily required, e.g. to take account of the change in territorial extent. [...] The Russian federation continues the legal personality of the former Soviet Union and is thus not a successor State in the sense just mentioned. The other former Soviet Republics are successor States.", United Kingdom Materials on International Law 1993, BYIL 1993, pp. 579 (636).

- ↑ Russia - Encyclopedia Britannica. Britannica.com (27 April 2010). Retrieved on 29 July 2013.

- ↑ http://pages.towson.edu/thompson/courses/regional/reference/sovietphysical.pdf

- ↑ "The causes of the October Revolution". BBC. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ↑ Evan Mawdsley (1 March 2007). The Russian Civil War. Pegasus Books. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-933648-15-6.

- ↑ Richard Sakwa The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union, 1917–1991: 1917–1991. Routledge, 1999. ISBN 9780415122900. pp. 140–143.

- ↑ Julian Towster. Political Power in the U.S.S.R., 1917–1947: The Theory and Structure of Government in the Soviet State Oxford Univ. Press, 1948. p. 106.

- ↑ (Russian) Voted Unanimously for the Union. Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ (Russian) Creation of the USSR at Khronos.ru.

- ↑ Lapin, G. G. (2000). "70 Years of Gidroproekt and Hydroelectric Power in Russia". Hydrotechnical Construction 34 (8/9): 374–379. doi:10.1023/A:1004107617449.

- ↑ (Russian) On GOELRO Plan — at Kuzbassenergo. Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The consolidation into a single-party regime took place during the first three and a half years after the revolution, which included the period of War Communism and an election in which multiple parties competed. See Leonard Schapiro, The Origin of the Communist Autocracy: Political Opposition in the Soviet State, First Phase 1917–1922. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1955, 1966.

- ↑ Lenin, V.I. Collected Works. pp. 152–164, Vol. 31.

The proletarian state must effect the transition to collective farming with extreme caution and only very gradually, by the force of example, without any coercion of the middle peasant.

- ↑ Stéphane Courtois; Mark Kramer (15 October 1999). Livre noir du Communisme: crimes, terreur, répression. Harvard University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2.

- ↑ Abbott Gleason (2009). A companion to Russian history. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 373. ISBN 978-1-4051-3560-3.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Geoffrey A. Hosking (2001). Russia and the Russians: a history. Harvard University Press. p. 469. ISBN 978-0-674-00473-3.

- ↑ Ukrainian 'Holodomor' (man-made famine) Facts and History. Holodomorct.org (28 November 2006). Retrieved on 29 July 2013.

- ↑ (Russian) Mel'tiukhov, Mikhail. Upushchennyi shans Stalina: Sovietskii Soiuz i bor'ba za Evropu 1939–1941. Moscow: Veche, 2000. ISBN 5-7838-1196-3.

- ↑ William J. Duiker (31 August 2009). Contemporary World History. Wadsworth Pub Co. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-495-57271-8.

- ↑ Denunciation of the neutrality pact 5 April 1945. (Avalon Project at Yale University)

- ↑ Soviet Declaration of War on Japan, 8 August 1945. (Avalon Project at Yale University)

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Geoffrey A. Hosking (2006). Rulers and victims: the Russians in the Soviet Union. Harvard University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-674-02178-5.

- ↑ "Main Intelligence Administration (GRU) Glavnoye Razvedovatel'noye Upravlenie – Russia / Soviet Intelligence Agencies". Fas.org. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ "Tank on the Moon". The Nature of Things with David Suzuki. 6 December 2007. CBC-TV.

- ↑ Kenneth S. Deffeyes, Beyond Oil: The View from Hubbert's Peak.

- ↑ The red blues — Soviet politics by Brian Crozier, National Review, 25 June 1990. Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Origins of Moral-Ethical Crisis and Ways to Overcome it by V.A.Drozhin Honoured Lawyer of Russia.

- ↑ Country Profile: Russia Foreign & Commonwealth Office of the United Kingdom.