South Carolina in the American Civil War

| State of South Carolina | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Columbia | ||||||||

| Largest city | Charleston | ||||||||

| Admission to Confederacy | February 8, 1861 (1st) | ||||||||

| Population | 703,708 Total * 301,302 free * 402,406 slave | ||||||||

| Forces supplied | 23% of white population Total * soldiers * sailors * marines | ||||||||

| Casualties | 12,992 dead | ||||||||

| Major garrisons/armories | Fort Sumter Charleston Harbor | ||||||||

| Governor | Francis Pickens (1860-1862) Milledge Bonham Andrew Magrath | ||||||||

| Lieutenant Governor | |||||||||

| Senators | Robert Woodward Barnwell James Lawrence Orr | ||||||||

| Representatives | List | ||||||||

| Returned to Union control | July 19, 1868 | ||||||||

|

|

Confederate States in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Border states |

|

| Dual governments |

|

| Territories |

South Carolina was a site of major political and military importance for the Confederacy during the American Civil War. The white population of the state strongly supported the institution of slavery long before the war. Political leaders such as John C. Calhoun and Preston Brooks had inflamed regional (and national) passions, and for years before the eventual start of the Civil War in 1861, voices cried for secession. On December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first Southern state to declare its secession and later formed the Confederacy. The first shots of the Civil War were fired in Charleston by its Citadel cadets upon a civilian merchant ship Star of the West bringing supplies to the beleaguered Federal garrison at Fort Sumter January 9, 1861. The April 1861 Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter ignited what became a four-year struggle that divided the nation.

South Carolina was a source of troops for the Confederate army, and as the war progressed, also for the Union as thousands of ex-slaves flocked to join the Union forces. The state also provided uniforms, textiles, food, and war material, as well as trained soldiers and leaders from The Citadel and other military schools. In contrast to most other Confederate states, South Carolina had a well-developed rail network linking all of its major cities without a break of gauge. Relatively free from Union occupation until the very end of the war, South Carolina hosted a number of prisoner of war camps. South Carolina also was the only Southern state not to harbor pockets of anti-secessionist fervor strong enough to send large amounts of white men to fight for the Union, as every other state in the Confederacy did.

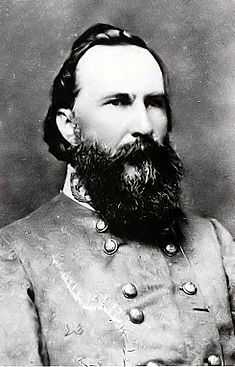

Among the leading generals from the Palmetto State were Wade Hampton III, one of the Confederacy's leading cavalrymen, Maxcy Gregg,killed in action at Fredericksburg, Joseph B. Kershaw, whose South Carolina infantry brigade saw some of the hardest fighting of the Army of Northern Virginia and James Longstreet who served in the Army of Northern Virginia under Robert E. Lee and in the Army of Tennessee under Gen. Braxton Bragg.

Secession

For decades, South Carolina political leaders had promoted regional passions with threats of nullification and secession in the name of states rights and protection of the interests of the slave power. On November 9, 1860 the South Carolina General Assembly passed a "Resolution to Call the Election of Abraham Lincoln as U.S. President a Hostile Act" and stated its intention to secede from the United States.[1]

In December 1860, amid the secession crisis, former South Carolinian congressman John McQueen wrote to a group of civic leaders in Richmond, Virginia, regarding the reasons as to why South Carolina was contemplating secession from the Union. In the letter, McQueen claimed that U.S. president-elect Abraham Lincoln supported equality and civil rights for African Americans as well as the abolition of slavery, and thus South Carolina, being opposed to such measures, was compelled to secede:

I have never doubted what Virginia would do when the alternatives present themselves to her intelligent and gallant people, to choose between an association with her sisters and the dominion of a people, who have chosen their leader upon the single idea that the African is equal to the Anglo-Saxon, and with the purpose of placing our slaves on equality with ourselves and our friends of every condition! and if we of South Carolina have aided in your deliverance from tyranny and degradation, as you suppose, it will only the more assure us that we have performed our duty to ourselves and our sisters in taking the first decided step to preserve an inheritance left us by an ancestry whose spirit would forbid its being tarnished by assassins. We, of South Carolina, hope soon to great you in a Southern Confederacy, where white men shall rule our destinies, and from which we may transmit to our posterity the rights, privileges and honor left us by our ancestors.[2][3]

On November 10, 1860 the General Assembly called for a Convention of the People of South Carolina to consider secession. Delegates were to be elected on December 6.[4] The secession convention convened in Columbia on December 17 and voted unanimously, 169-0, to secede from the United States. The convention then adjourned to Charleston to draft an ordinance of secession. When the ordinance was adopted on December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first southern U.S. state to declare its secession from the Union. United States President James Buchanan declared the ordinance illegal but did not act to stop it. A committee of the convention also drafted a Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina which was adopted on December 24.[5] The secession declaration stated the primary reasoning behind South Carolina's declaring of secession from the Union, which was described as:

... increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the Institution of Slavery ...[5]

The South Carolinian secession declaration of December 1860 also channeled some elements from the U.S. Declaration of Independence from July 1776. However, the South Carolinian version omitted the phrases that "all men are created equal" and "that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights". Professor and historian Harry V. Jaffa noted these omissions as significant in his 2000 book, A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War:

South Carolina cites, loosely, but with substantial accuracy, some of the language of the original Declaration. That Declaration does say that it is the right of the people to abolish any form of government that becomes destructive of the ends for which it was established. But South Carolina does not repeat the preceding language in the earlier document: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal'...[6]

The following day, on December 25, a South Carolinian convention delivered an "Address to the Slaveholding States":

We prefer, however, our system of industry, by which labor and capital are identified in interest, and capital, therefore, protects labor–by which our population doubles every twenty years–by which starvation is unknown, and abundance crowns the land–by which order is preserved by unpaid police, and the most fertile regions of the world, where the white man cannot labor, are brought into usefulness by the labor of the African, and the whole world is blessed by our own productions. ... We ask you to join us, in forming a Confederacy of Slaveholding States.[7]

The state adopted the palmetto flag as its banner.[8] South Carolina after secession was frequently called the "Palmetto Republic".[9]

After South Carolina declared its secession, former congressman James L. Petigru famously remarked, "South Carolina is too small for a republic and too large for an insane asylum."[10] Soon afterwards, South Carolina began preparing for a presumed Federal military response while working to convince other southern states to secede as well and join in a confederacy of southern states.

On February 4, 1861, in Montgomery, Alabama, a convention consisting of delegates from South Carolina, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and Louisiana met to form a new constitution and government modeled on that of the United States.[11] On February 8, 1861, South Carolina officially joined the Confederate States of America.

American Civil War

Fort Sumter

Six days after secession, on the day after Christmas, Major Robert Anderson, commander of the U.S. troops in Charleston, withdrew his men to the island fortress of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. South Carolina militia swarmed over the abandoned mainland batteries and trained their guns on the island. Sumter was the key position for preventing a naval attack upon Charleston, so secessionists were determined not to allow federal forces to remain there indefinitely. More importantly, South Carolina's claim of independence would look empty if U.S. federal forces controlled its largest harbor. On January 9, 1861, the U.S. ship Star of the West approached to resupply the fort. Cadets from The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina fired upon the Star of the West, striking the ship three times and causing it to retreat back to New York.

Mississippi declared its secession several weeks after South Carolina, and five other states of the lower South soon followed. Both the outgoing Buchanan administration and President-elect Lincoln denied that any state had a right to secede. On February 4, a congress of the seven seceding states met in Montgomery, Alabama, and approved a new constitution for the Confederate States of America. South Carolina entered the Confederacy on February 8, 1861, fewer than six weeks after declaring itself the independent State of South Carolina.

Upper Southern states such as Virginia and North Carolina, which had initially voted against secession, called a peace conference, to little effect. Meanwhile, Virginian orator Roger Pryor barreled into Charleston and proclaimed that the only way to get his state to join the Confederacy was for South Carolina to instigate war with the United States. The obvious place to start was right in the midst of Charleston Harbor.

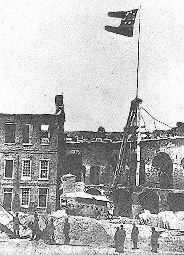

On April 10, the Mercury reprinted stories from New York papers that told of a naval expedition that had been sent southward toward Charleston. Lincoln advised the governor of South Carolina that the ships were sent to resupply the fort, not to reinforce it. The Carolinians could no longer wait if they hoped to take the fort before the U.S. Navy arrived. About 6,000 men were stationed around the rim of the harbor, ready to take on the 60 men in Fort Sumter. At 4:30 a.m. on April 12, after two days of intense negotiations, and with Union ships approaching the harbor, the firing began. Students from The Citadel were among those firing the first shots of the war, though Edmund Ruffin is usually credited with firing the first shot. Thirty-four hours later, Anderson's men raised the white flag and were allowed to leave the fort with colors flying and drums beating, saluting the U.S. flag with a 50-gun salute before taking it down. During this salute, one of the guns exploded, killing a young soldier—the only casualty of the bombardment and the first casualty of the war.

In December 1861, South Carolina received $100,000 from Georgia after a disastrous fire in Charleston.

The war ends

The South was at a disadvantage in number, weaponry, and maritime skills—few southerners were sailors. Federal ships sailed south and blocked off one port after another. As early as November, Union troops occupied the Sea Islands in the Beaufort area, establishing an important base for the men and ships who would obstruct the ports at Charleston and Savannah. When the plantation owners, many of which had already gone off with the Confederate Army elsewhere, fled the area, the Sea Island slaves became the first "freedmen" of the war, and the Sea Islands became the laboratory for Northern plans to educate the African Americans for their eventual role as full American citizens.

Despite South Carolina's important role in the start of the war, and a long unsuccessful attempt to take Charleston from 1863 onward, few military engagements occurred within the state's borders until 1865, when Sherman's Army, having already completed its March to the Sea in Savannah, marched to Columbia and leveled most of the town, as well as a number of towns along the way and afterward. South Carolina lost 12,922 men to the war, 23% of its male white population of fighting age, and the highest percentage of any state in the nation. Sherman's 1865 march through the Carolinas resulted in the burning of Columbia and numerous other towns. The destruction his troops wrought upon South Carolina was even worse than in Georgia, because many of his men bore a particular grudge against the state and its citizens, who they blamed for starting the war. One of Sherman's men declared, "Here is where treason began and, by God, here is where it shall end!"[12] Poverty would mark the state for generations to come.

On February 21, 1865, with the Confederate forces finally evacuated from Charleston, the black 54th Massachusetts Regiment marched through the city. At a ceremony at which the U.S. flag was once again raised over Fort Sumter, former fort commander Robert Anderson was joined on the platform by two men: African American Union hero Robert Smalls and the son of Denmark Vesey.

Notable Civil War leaders from South Carolina

-

Lt. Gen.

Wade Hampton -

Maj. Gen. and Gov.

Milledge Luke Bonham -

Maj. Gen.

Joseph B. Kershaw -

Lt. Gen.

James Longstreet -

Brig. Gen.

Maxcy Gregg

Battles in South Carolina

- Battle of Fort Sumter

- Battle of Port Royal

- Battle of Secessionville

- Battle of Simmon's Bluff

- First Battle of Charleston Harbor

- Second Battle of Charleston Harbor

- Second Battle of Fort Sumter

- First Battle of Fort Wagner

- Battle of Grimball's Landing

- Second Battle of Fort Wagner (Morris Island)

- Battle of Honey Hill

- Battle of Tulifinny

- Battle of Rivers' Bridge

- Battle of Anderson County

- Battle of Brattonsville

- Battle of Broxton's Bridge

- Battle of Cheraw

- Battle of Gamble's Hotel (The Columns)

See also

- Charleston, South Carolina in the American Civil War

- Confederate States of America - animated map of state secession and confederacy

- List of South Carolina Confederate Civil War units

- List of South Carolina Union Civil War units

- Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Slaves and the American Civil War

Notes

- ↑ "Resolution to Call the Election of Abraham Lincoln as U.S. President a Hostile Act and to Communicate to Other Southern States South Carolina's Desire to Secede from the Union." 9 November 1860. Resolutions of the General Assembly, 1779-1879. S165018. South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, S.C.

- ↑ Rhea, Gordon (January 25, 2011). "Why Non-Slaveholding Southerners Fought". Civil War Trust. Civil War Trust. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ↑ McQueen, John (December 24, 1860). "Correspondence to T. T. Cropper and J. R. Crenshaw". Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ Cauthen, Charles Edward; Power, J. Tracy. South Carolina goes to war, 1860-1865. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2005. Originally published: Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1950. ISBN 978-1-57003-560-9. p. 60.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "'Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union,' 24 December 1860". Teaching American History in South Carolina Project. 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ↑ Jaffa, Harry V. (2000). A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 231.

- ↑ State of South Carolina (December 25, 1860). "Address of the people of South Carolina to the people of the Slaveholding States of the United States". Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ↑ Edgar, Walter. South Carolina: A History, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press:1998. ISBN 978-1-57003-255-4. p. 619

- ↑ Cauthen, Charles Edward; Power, J. Tracy. South Carolina goes to war, 1860-1865. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2005. Originally published: Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1950. ISBN 978-1-57003-560-9. p. 79.

- ↑ Burger, Ken (February 13, 2010). "Too large to be an asylum". The Post and Courier (Charleston, South Carolina: Evening Post Publishing Co). Retrieved April 22, 2010. Paragraph 4

- ↑ Lee, Jr., Charles Robert. The Confederate Constitutions. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1963, 60.

- ↑ McPherson, James M. This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War. Oxford University Press, 2009

References

- Burger, Ken (February 13, 2010). "Too large to be an asylum". The Post and Courier (Charleston, South Carolina: Evening Post Publishing Co). Retrieved April 22, 2010..

- Cauthen, Charles Edward; Power, J. Tracy. South Carolina goes to war, 1860-1865. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2005. Originally published: Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1950. ISBN 978-1-57003-560-9.

- Edgar, Walter. South Carolina: A History, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press:1998. ISBN 978-1-57003-255-4.

- Rogers Jr. George C. and C. James Taylor. A South Carolina Chronology, 1497-1992 2nd Ed. (1994)

- Wallace, David Duncan. South Carolina: A Short History, 1520-1948 (1951) standard scholarly history

- WPA. South Carolina: A Guide to the Palmetto State (1941)

- Wright, Louis B. South Carolina: A Bicentennial History' (1976)

Further reading

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: American Civil War |

- National Park Service map of Civil War sites in South Carolina

- Annual Re-enactment of The Battle of Secessionville

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.png)