Solid of revolution

In mathematics, engineering, and manufacturing, a solid of revolution is a solid figure obtained by rotating a plane curve around some straight line (the axis) that lies on the same plane.

Assuming that the curve does not cross the axis, the solid's volume is equal to the length of the circle described by the figure's centroid multiplied by the figure's area (Pappus's second centroid Theorem).

A representative disk is a three-dimensional volume element of a solid of revolution. The element is created by rotating a line segment (of length w) around some axis (located r units away), so that a cylindrical volume of πr2w units is enclosed.

Finding the volume

Two common methods for finding the volume of a solid of revolution are the disc method and the shell method of integration. To apply these methods, it is easiest to draw the graph in question; identify the area that is to be revolved about the axis of revolution; determine the volume of either a disc-shaped slice of the solid, with thickness δx, or a cylindrical shell of width δx; and then find the limiting sum of these volumes as δx approaches 0, a value which may be found by evaluating a suitable integral.

Disc method

The disc method is used when the slice that was drawn is perpendicular to the axis of revolution; i.e. when integrating parallel to the axis of revolution.

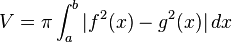

The volume of the solid formed by rotating the area between the curves of  and

and  and the lines

and the lines  and

and  about the x-axis is given by

about the x-axis is given by

If g(x) = 0 (e.g. revolving an area between curve and x-axis), this reduces to:

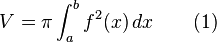

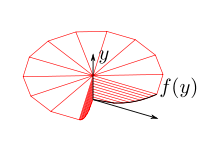

The method can be visualized by considering a thin horizontal rectangle at y between  on top and

on top and  on the bottom, and revolving it about the y-axis; it forms a ring (or disc in the case that

on the bottom, and revolving it about the y-axis; it forms a ring (or disc in the case that  ), with outer radius f(y) and inner radius g(y). The area of a ring is

), with outer radius f(y) and inner radius g(y). The area of a ring is  , where R is the outer radius (in this case f(y)), and r is the inner radius (in this case g(y)). Summing up all of the areas along the interval gives the total volume. The volume of each infinitesimal disc is therefore

, where R is the outer radius (in this case f(y)), and r is the inner radius (in this case g(y)). Summing up all of the areas along the interval gives the total volume. The volume of each infinitesimal disc is therefore  . An infinite sum of the discs between a and b manifests itself as integral (1).

. An infinite sum of the discs between a and b manifests itself as integral (1).

Cylinder method

The cylinder method is used when the slice that was drawn is parallel to the axis of revolution; i.e. when integrating perpendicular to the axis of revolution.

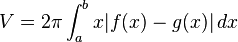

The volume of the solid formed by rotating the area between the curves of  and

and  and the lines

and the lines  and

and  about the y-axis is given by

about the y-axis is given by

If g(x) = 0 (e.g. revolving an area between curve and x-axis), this reduces to:

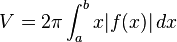

The method can be visualized by considering a thin vertical rectangle at x with height ![[f(x) - g(x)]](../I/m/e4a798b9cde10ee16ef932c9c5a8fee3.png) , and revolving it about the y-axis; it forms a cylindrical shell. The lateral surface area of a cylinder is

, and revolving it about the y-axis; it forms a cylindrical shell. The lateral surface area of a cylinder is  , where r is the radius (in this case x), and h is the height (in this case

, where r is the radius (in this case x), and h is the height (in this case ![[f(x) - g(x)]](../I/m/e4a798b9cde10ee16ef932c9c5a8fee3.png) ). Summing up all of the surface areas along the interval gives the total volume.

). Summing up all of the surface areas along the interval gives the total volume.

Parametric form

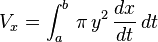

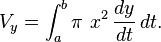

When a curve is defined by its parametric form  in some interval

in some interval ![[a,b]](../I/m/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.png) , the volumes of the solids generated by revolving the curve around the x-axis or the y-axis are given by[1]

, the volumes of the solids generated by revolving the curve around the x-axis or the y-axis are given by[1]

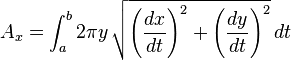

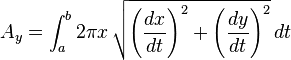

Under the same circumstances the areas of the surfaces of the solids generated by revolving the curve around the x-axis or the y-axis are given by[2]

See also

- Gabriel's Horn

- Guldinus theorem

- Pseudosphere

- Surface of revolution

Notes

- ↑ Sharma, A.K. (2005). Application Of Integral Calculus. Discovery Publishing House. p. 168. ISBN 81-7141-967-4., Chapter 3, page 168

- ↑ Singh (1993). Engineering Mathematics (6 ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 6.90. ISBN 0-07-014615-2., Chapter 6, page 6.90

References

- CliffsNotes.com. Volumes of Solids of Revolution. 12 Apr 2011 <http://www.cliffsnotes.com/study_guide/topicArticleId-39909,articleId-39907.html>.

- Frank Ayres, Elliott Mendelson. Schaum's Outlines: Calculus. McGraw-Hill Professional 2008, ISBN 978-0-07-150861-2. pp. 244–248 (online copy, p. 244, at Google Books)

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Solid of Revolution", MathWorld.