Socialization

Socialization, also spelled socialisation, is a term used by sociologists, social psychologists, anthropologists, political scientists and educationalists to refer to the lifelong process of inheriting and disseminating norms, customs and ideologies, providing an individual with the skills and habits necessary for participating within his or her own society. Socialization is thus "the means by which social and cultural continuity are attained".[1][2]

Socialization describes a process which may lead to desirable outcomes – sometimes labeled "moral" – as regards the society where it occurs. Individual views on certain issues, for instance race or economics, are influenced by the society's consensus and usually tend toward what that society finds acceptable or "normal". Many socio-political theories postulate that socialization provides only a partial explanation for human beliefs and behaviors, maintaining that agents are not blank slates predetermined by their environment;[3] scientific research provides evidence that people are shaped by both social influences and genes.[4][5][6][7] Genetic studies have shown that a person's environment interacts with his or her genotype to influence behavioral outcomes.[8]

Theories

Socialization is the process by which human infants begin to acquire the skills necessary to perform as a functioning member of their society, and is the most influential learning process one can experience.[9] Unlike many other living species, whose behavior is biologically set, humans need social experiences to learn their culture and to survive.[10] Although cultural variability manifests in the actions, customs, and behaviors of whole social groups (societies), the most fundamental expression of culture is found at the individual level. This expression can only occur after an individual has been socialized by his or her parents, family, extended family, and extended social networks. This reflexive process of both learning and teaching is how cultural and social characteristics attain continuity. Many scientists say socialization essentially represents the whole process of learning throughout the life course and is a central influence on the behavior, beliefs, and actions of adults as well as of children.[11]

Klaus Hurrelmann

From the late 1980s, sociological and psychological theories have been connected with the term socialization. One example of this connection is the theory of Klaus Hurrelmann. In his book "Social Structure and Personality Development" (Hurrelmann 1989/2009), he develops The "Model of Productive Processing of Reality (PPR)." The core idea is that socialization refers to an individual's personality development. It is the result of the productive processing of interior and exterior realities. Bodily and mental qualities and traits constitute a person's inner reality; the circumstances of the social and physical environment embody the external reality. Reality processing is productive because human beings actively grapple with their lives and attempt to cope with the attendant developmental tasks. The success of such a process depends on the personal and social resources available. Incorporated within all developmental tasks is the necessity to reconcile personal individuation and social integration and so secure the "I-dentity." (Hurrelmann1989/2009: 42)

Lawrence Kohlberg

Lawrence Kohlberg's (1981) theory of moral development studied moral reasoning (how individuals reason situations as right from wrong) within three stages of young childhood. The first is the pre-conventional stage, where children experience the world in terms of pain and pleasure. Second, the conventional stage appears in the teen years of maturation. Teenagers learn to define right and wrong according to the desires of their parents and begin to conform to cultural norms resulting in a decrease of selfishness. The last stage of moral development is the post-conventional level where people move beyond society's norms and consider abstract ethical principles.[12]

Carol Gilligan

Carol Gilligan compared the moral development of girls and boys in her theory of gender and moral development. She claimed (1982, 1990) that boys have a justice perspective meaning that they rely on formal rules to define right and wrong. Girls, on the other hand, have a care and responsibility perspective where personal relationships are considered when judging a situation. Gilligan also studied the effect of gender on self-esteem. She claimed that society's socialization of females is the reason why girls' self-esteem diminishes as they grow older. Girls struggle to regain their personal strength when moving through adolescence as they have fewer female teachers and most authority figures are men.[13]

Erik H. Erikson

Erik H. Erikson (1902–1994) explained the challenges throughout the life course. The first stage in the life course is infancy, where babies learn trust and mistrust. The second stage is toddlerhood where children around the age of two struggle with the challenge of autonomy versus doubt. In stage three, preschool, children struggle to understand the difference between initiative and guilt. Stage four, pre-adolescence, children learn about industriousness and inferiority. In the fifth stage called adolescence, teenagers experience the challenge of gaining identity versus confusion. The sixth stage, young adulthood, is when young people gain insight to life when dealing with the challenge of intimacy and isolation. In stage seven, or middle adulthood, people experience the challenge of trying to make a difference (versus self-absorption). In the final stage, stage eight or old age, people are still learning about the challenge of integrity and despair.[14]

George Herbert Mead

George Herbert Mead (1863–1931) developed a theory of social behaviorism to explain how social experience develops an individual's self-concept. Mead's central concept is the self: It is composed of self-awareness and self-image. Mead claimed that the self is not there at birth, rather, it is developed with social experience. Since social experience is the exchange of symbols, people tend to find meaning in every action. Seeking meaning leads us to imagine the intention of others. Understanding intention requires imagining the situation from the others' point of view. In effect, others are a mirror in which we can see ourselves. Charles Horton Cooley (1902-1983) coined the term looking glass self, which means self-image based on how we think others see us. According to Mead the key to developing the self is learning to take the role of the other. With limited social experience, infants can only develop a sense of identity through imitation. Gradually children learn to take the roles of several others. The final stage is the generalized other, which refers to widespread cultural norms and values we use as a reference for evaluating others.[15]

Judith R. Harris

Judith R. Harris (b. 1938) graduated magna cum laude with her master's degree in psychology from Harvard University. She received the George A. Miller Award for her proposed theory of group socialization (GS theory). This theory states that a child’s adult personality is determined by childhood and adolescent peer groups outside of the home environment and that “parental behaviors have no effect on the psychological characteristics their children will have as adults.” Harris proposes this theory based on behavioral genetics, sociological views of group processes, context-specific learning, and evolutionary theory.[16] While Harris proposed this theory, she attributes the original idea to Eleanor E. Maccoby and John A. Martin both of whom are doctors at Stanford University and wrote the chapter on family socialization found in the fourth edition of The Handbook of Child Psychology. After extensively reviewing the research conducted on parent-child interactions, Maccoby and Martin (1983) state that their findings suggest that parental behavior and the home environment has either no effect on the social development of children, or the effect varies significantly between children.[17]

Behavioral genetics suggest that up to fifty percent of the variance in adult personality is due to genetic differences.[18] The environment in which a child is raised accounts for only approximately ten percent in the variance of an adult’s personality.[19] As much as twenty percent of the variance is due measurement error.[20] This suggests that only a very small part of an adult’s personality is influenced by factors parents control (i.e. the home environment). Harris claims that while it’s true that siblings don’t have identical experiences in the home environment (making it difficult to associate a definite figure to the variance of personality due to home environments), the variance found by current methods is so low that researchers should look elsewhere to try to account for the remaining variance.[16]

Harris also states that developing long-term personality characteristics away from the home environment would be evolutionarily beneficial because future success is more likely to depend on interactions with peers than interactions with parents and siblings. Also, because of already existing genetic similarities with parents, developing personalities outside of childhood home environments would further diversify individuals, increasing their evolutionary success.[16]

Language Socialization

Based on comparative research in different societies, focusing on the role of language in child development, linguistic anthropologists Elinor Ochs and Bambi Schieffelin have developed the theory of language socialization.[21] They discovered that the processes of enculturation and socialization do not occur apart from the process of language acquisition, but that children acquire language and culture together in what amounts to an integrated process. Members of all societies socialize children both to and through the use of language; acquiring competence in a language, the novice is by the same token socialized into the categories and norms of the culture, while the culture, in turn, provides the norms of the use of language.

Stages

Richard Moreland and John Levine (1982) created a model of group socialization based upon the assumption that individuals and groups change their evaluations and commitments to each other over time. Since these changes happen in all groups, Moreland and Levine speculate that there is a predictable sequence of stages that occur in order for an individual to transition through a group.

Moreland and Levine identify five stages of socialization which mark this transition; investigation, socialization, maintenance, resocialization, and remembrance. During each stage, the individual and the group evaluate each other which leads to an increase or decrease in commitment to socialization. This socialization pushes the individual from prospective, new, full, marginal, and ex member.

Stage 1: Investigation This stage is marked by a cautious search for information. The individual compares groups in order to determine which one will fulfill their needs (reconnaissance), while the group estimates the value of the potential member (recruitment). The end of this stage is marked by entry to the group, whereby the group asks the individual to join and they accept the offer.

Stage 2: Socialization Now that the individual has moved from prospective member to new member, they must accept the group’s culture. At this stage, the individual accepts the group’s norms, values, and perspectives (assimilation), and the group adapts to fit the new member’s needs (accommodation). The acceptance transition point is then reached and the individual becomes a full member. However, this transition can be delayed if the individual or the group reacts negatively. For example, the individual may react cautiously or misinterpret other members’ reactions if they believe that they will be treated differently as a new comer.

Stage 3: Maintenance During this stage, the individual and the group negotiate what contribution is expected of members (role negotiation). While many members remain in this stage until the end of their membership, some individuals are not satisfied with their role in the group or fail to meet the group’s expectations (divergence).

Stage 4: Resocialization -If the divergence point is reached, the former full member takes on the role of a marginal member and must be resocialized. There are two possible outcomes of resocialization: differences are resolved and the individual becomes a full member again (convergence), or the group expels the individual or the individual decides to leave (exit).

Stage 5: Remembrance In this stage, former members reminisce about their memories of the group, and make sense of their recent departure. If the group reaches a consensus on their reasons for departure, conclusions about the overall experience of the group become part of the group’s tradition.

Types

Primary socialization for a child is very important because it sets the ground work for all future socialization. Primary Socialization occurs when a child learns the attitudes, values, and actions appropriate to individuals as members of a particular culture. It is mainly influenced by the immediate family and friends. For example if a child saw his/her mother expressing a discriminatory opinion about a minority group, then that child may think this behavior is acceptable and could continue to have this opinion about minority groups.

Secondary socialization Secondary socialization refers to the process of learning what is the appropriate behavior as a member of a smaller group within the larger society. Basically, it is the behavioral patterns reinforced by socializing agents of society. Secondary socialization takes place outside the home. It is where children and adults learn how to act in a way that is appropriate for the situations they are in.[22] Schools require very different behavior from the home, and Children must act according to new rules. New teachers have to act in a way that is different from pupils and learn the new rules from people around them.[22] Secondary Socialization is usually associated with teenagers and adults, and involves smaller changes than those occurring in primary socialization. Such examples of Secondary Socialization are entering a new profession or relocating to a new environment or society.

Anticipatory socialization Anticipatory socialization refers to the processes of socialization in which a person "rehearses" for future positions, occupations, and social relationships. For example, a couple might move in together before getting married in order to try out, or anticipate, what living together will be like.[23] Research by Kenneth J. Levine and Cynthia A. Hoffner suggests that parents are the main source of anticipatory socialization in regards to jobs and careers.[24]

Re-socialization Re-socialization refers to the process of discarding former behavior patterns and reflexes, accepting new ones as part of a transition in one's life. This occurs throughout the human life cycle.[25] Re-socialization can be an intense experience, with the individual experiencing a sharp break with his or her past, as well as a need to learn and be exposed to radically different norms and values. One common example involves re-socialization through a total institution, or "a setting in which people are isolated from the rest of society and manipulated by an administrative staff". Re-socialization via total institutions involves a two step process: 1) the staff work to root out a new inmate's individual identity & 2) the staff attempt to create for the inmate a new identity.[26] Other examples of this are the experience of a young man or woman leaving home to join the military, or a religious convert internalizing the beliefs and rituals of a new faith. An extreme example would be the process by which a transsexual learns to function socially in a dramatically altered gender role.

Organizational socialization

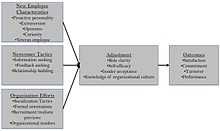

Organizational socialization is the process whereby an employee learns the knowledge and skills necessary to assume his or her organizational role.[27] As newcomers become socialized, they learn about the organization and its history, values, jargon, culture, and procedures. This acquired knowledge about new employees' future work environment affects the way they are able to apply their skills and abilities to their jobs. How actively engaged the employees are in pursuing knowledge affects their socialization process.[28] They also learn about their work group, the specific people they work with on a daily basis, their own role in the organization, the skills needed to do their job, and both formal procedures and informal norms. Socialization functions as a control system in that newcomers learn to internalize and obey organizational values and practices.

Group socialization Group socialization is the theory that an individual's peer groups, rather than parental figures, influences his or her personality and behavior in adulthood.[16] Adolescents spend more time with peers than with parents. Therefore, peer groups have stronger correlations with personality development than parental figures do.[29] For example, twin brothers, whose genetic makeup are identical, will differ in personality because they have different groups of friends, not necessarily because their parents raised them differently.

Entering high school is a crucial moment in many adolescent's lifespan involving the branching off from the restraints of their parents. When dealing with new life challenges, adolescents take comfort in discussing these issues within their peer groups instead of their parents.[30] Peter Grier, staff writer of the Christian Science Monitor describes this occurrence as,"Call it the benign side of peer pressure. Today's high-schoolers operate in groups that play the role of nag and nanny-in ways that are both beneficial and isolating."[31]

Gender socialization Henslin (1999:76) contends that "an important part of socialization is the learning of culturally defined gender roles." Gender socialization refers to the learning of behavior and attitudes considered appropriate for a given sex. Boys learn to be boys and girls learn to be girls. This "learning" happens by way of many different agents of socialization. The family is certainly important in reinforcing gender roles, but so are one’s friends, school, work and the mass media. Gender roles are reinforced through "countless subtle and not so subtle ways" (1999:76).

As parents are present in a child's life from the beginning, their influence in a child's early socialization is very important, especially in regards to gender roles. Sociologists have identified four ways in which parents socialize gender roles in their children: Shaping gender related attributes through toys and activities, differing their interaction with children based on the sex of the child, serving as primary gender models, and communicating gender ideals and expectations.[32]

Racial socialization Racial socialization has been defined as "the developmental processes by which children acquire the behaviors, perceptions, values, and attitudes of an ethnic group, and come to see themselves and others as members of the group".[33] The existing literature conceptualizes racial socialization as having multiple dimensions. Researchers have identified five dimensions that commonly appear in the racial socialization literature: cultural socialization, preparation for bias, promotion of mistrust, egalitarianism, and other.[34] Cultural socialization refers to parenting practices that teach children about their racial history or heritage and is sometimes referred to as pride development. Preparation for bias refers to parenting practices focused on preparing children to be aware of, and cope with, discrimination. Promotion of mistrust refers to the parenting practices of socializing children to be wary of people from other races. Egalitarianism refers to socializing children with the belief that all people are equal and should be treated with a common humanity.[34]

Planned socialization Planned socialization occurs when other people take actions designed to teach or train others—from infancy on.[35]

Natural Socialization Natural socialization occurs when infants and youngsters explore, play and discover the social world around them. Natural socialization is easily seen when looking at the young of almost any mammalian species (and some birds). Planned socialization is mostly a human phenomenon; and all through history, people have been making plans for teaching or training others. Both natural and planned socialization can have good and bad features: It is wise to learn the best features of both natural and planned socialization and weave them into our lives.[35]

Positive socialization Positive socialization is the type of social learning that is based on pleasurable and exciting experiences. We tend to like the people who fill our social learning processes with positive motivation, loving care, and rewarding opportunities.[35]

Negative socialization Negative socialization occurs when others use punishment, harsh criticisms or anger to try to "teach us a lesson;" and often we come to dislike both negative socialization and the people who impose it on us.[35] There are all types of mixes of positive and negative socialization; and the more positive social learning experiences we have, the happier we tend to be—especially if we learn useful information that helps us cope well with the challenges of life. A high ratio of negative to positive socialization can make a person unhappy, defeated or pessimistic about life.[35]

Social institutions

In the social sciences, institutions are the structures and mechanisms of social order and cooperation governing the behavior of a set of individuals within a given human collectivity. Institutions are identified with a social purpose and permanence, transcending individual human lives and intentions, and with the making and enforcing of rules governing cooperative human behavior.[36] Types of institution include:

- The Family The family is the most important agent of socialization because it is the center of the child's life, as infants are totally dependent on others. Not all socialization is intentional, it depends on the surrounding. The most profound affect is gender socialization, however the family also shoulders the task of teaching children cultural values and attitudes about themselves and others. Children learn continuously from the environment that adults create. Children also become aware of class at a very early age and assign different values to each class accordingly.[37]

- Religion Agents of socialization differ in effects across religious traditions. Some believe religion is like an ethnic or cultural category, making it less likely for the individuals to break from religious affiliations and be more socialized in this setting. Parental religious participation is the most influential part of religious socialization—more so than religious peers or religious beliefs.[38]

- Peer group A peer group is a social group whose members have interests, social positions and age in common. This is where children can escape supervision and learn to form relationships on their own. The influence of the peer group typically peaks during adolescence however peer groups generally only affect short term interests unlike the family which has long term influence.[39]

- Economic systems Socialization within an economic system is the process of learning the consequences of economic decisions. Socialization impacts decisions regarding "acceptable alternatives for consumption," "social values of consumption alternatives," the "establishment of dominant values," and "the nature of involvement in consumption".[40] Unfortunately, one and the same word, Socialization, in this context is used to describe counterposed phenomena: the growing centralization and interdependence of capitalist society under the control of an elite; and the possibility of a democratic, bottom-up control by the majority. Thus, "socialization" describes two very different ways in which society can become more social: under capitalism, there is a trend toward a growing centralization and planning that is eventually global, but takes place from the top down; under socialism, that process is subjected to democratic control from below by the people and their communities.[41]

- Legal systems Children are pressured from both parents and peers to conform and obey certain laws or norms of the group/community. Parents’ attitudes toward legal systems influence children’s views as to what is legally acceptable.[42] For example, children whose parents are continually in jail are more accepting of incarceration.

- Penal systems: The penal systems act as an agent of socialization upon prisoners and the guards. Prison is a separate environment from that of normal society; prisoners and guards form their own communities and create their own social norms. Guards serve as "social control agents" who discipline and provide security.[43] From the view of the prisoners, the communities can be oppressive and domineering, causing feelings of defiance and contempt towards the guards.[43] Because of the change in societies, prisoners experience loneliness, a lack of emotional relationships, a decrease in identity and "lack of security and autonomy".[44] Both the inmates and the guards feel tense, fearful, and defensive, which creates an uneasy atmosphere within the community.[43]

- Language People learn to socialize differently depending on the specific language and culture in which they live.[21] A specific example of this is code switching. This is where immigrant children learn to behave in accordance with the languages used in their lives: separate languages at home and in peer groups (mainly in educational settings).[45] Depending on the language and situation at any given time, people will socialize differently [16]

- Mass media The mass media are the means for delivering impersonal communications directed to a vast audience. The term media comes from Latin meaning, "middle," suggesting that the media's function is to connect people. Since mass media has enormous effects on our attitudes and behavior, notably in regards to aggression, it is an important contributor to the socialization process.[10]

Some sociologists and theorists of culture have recognized the power of mass communication as a socialization device. Denis McQuail recognizes the argument:

… the media can teach norms and values by way of symbolic reward and punishment for different kinds of behavior as represented in the media. An alternative view is that it is a learning process whereby we all learn how to behave in certain situations and the expectations which go with a given role or status in society.—McQuail 2005: 494.

Learning can be social or nonsocial.[46] Consider the example of a child learning about bees. If is child is exploring and playing with no one else around, the child may see a bee and touch it (out of curiosity). If the child is stung by the bee, the child learns that touching bees is associated with pain. This is nonsocial learning, since no one else was around. In contrast, a child may benefit from social learning about bees. If the child is with mom, dad or anyone else, the child's inquisitive approach to a bee may lead to some kind of social intervention. Maybe Aunt Emy sees the child reaching for a bee and simply points the child in another direction, saying "Look at that pretty butterfly." Maybe Uncle Ed would say, "Don’t touch the bee, because it can hurt you and make you cry." Maybe Mom would have said, "Honey, stay away from bees because they sting." There are all sorts of ways that people can interact with a child to help the child learn to avoid ever being stung. Any and all of these social interventions allow the child to benefit from social learning, though some of these social interventions may be more educational and useful than others.[46]

Other uses

To "socialize" may also mean simply to associate or mingle with people socially. In American English, "socialized" has come to refer, usually in a pejorative sense, to the ownership structure of socialism or to the expansion of the welfare state.[47] Traditionally, socialists and Marxists both used the term "socialization of industry" to refer to the reorganization of institutions so that the workers are all owners (cooperatives) and to refer to the implementation of workplace democracy.[48]

See also

- Acculturation

- Cultural assimilation

- Enculturation

- Internalisation

- Indoctrination

- Organizational socialization

- Political socialization

- Reciprocal socialization

- Socialization of animals

- Social construction

- Social identity

- Structure and agency

- Shame society

- TPI-theory

- Guilt society

- Value (personal and cultural)

- Circle of friends (disability)

- Memetics

- Nature versus nurture

- Structure and agency

- Social skills

- Stereotype

References

- ↑ Clausen, John A. (ed.) (1968) Socialization and Society, Boston: Little Brown and Company, p. 5.

- ↑ Macionis, Gerber, Sociology, 7th Canadian ed. (Pearson Canada, 2010), p. 104.

- ↑ Pinker, Steven. The Blank Slate. New York: Penguin Books, 2002.

- ↑ Dusheck, Jennie, "The Interpretation of Genes". Natural History, October 2002.

- ↑ Carlson, N. R. et al. (2005) Psychology: the science of behavior. Pearson (3rd Canadian edition). ISBN 0-205-45769-X.

- ↑ Ridley, M. (2003) Nature Via Nurture: Genes, Experience, and What Makes us Human. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-200663-4.

- ↑ Westen, D. (2002) Psychology: Brain, Behavior & Culture. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-38754-1.

- ↑ Kendler, K. S. and Baker, J. H. (2007). "Genetic influences on measures of the environment: a systematic review". Psychological Medicine 37 (5): 615–626. doi:10.1017/S0033291706009524. PMID 17176502.

- ↑ Billingham, M. (2007) Sociological Perspectives p.336 In Stretch, B. and Whitehouse, M. (eds.) (2007) Health and Social Care Book 1. Oxford: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-49915-0

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Macionis, John J., and Linda M. Gerber. Sociology. Toronto: Pearson Canada, 2011. Print.

- ↑ MLA Style: "socialization." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Student and Home Edition. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2010.

- ↑ Macionis, Gerber 2010 108

- ↑ Macionis, Gerber, John, Linda (2010). Sociology 7th Canadian Ed. Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Inc.. pp.109

- ↑ Macionis, Gerber, John, Linda (2010). Sociology 7th Canadian Ed. Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Inc. p. 111.

- ↑ Macionis, Gerber, John, Linda (2010). Sociology 7th Canadian Ed. Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Inc. p. 109.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Harris, J. R. (1995). Where is the child’s environment? A group socialization theory of development. Psychological Review, 102(3), pp. 458-489.

- ↑ Maccoby, E. E. & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P. H. Mussen (Series Ed.) & E. M. Hetherington (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed., pp. 1-101). New York: Wiley.

- ↑ McGue, M., Bouchard, T. J. Jr., Iacono, W. G. & Lykken, D. T. (1993). Behavioral genetics of cognitive ability: A life-span perspective. In R. Plomin & G. E. McClearn (Eds.), Nature, nurture, and psychology (pp. 59-76). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ Plomin, R. & Daniels, D. (1987). Why are children in the same family so different from one another? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 10, 1-60.

- ↑ Plomin, R. (1990). Nature and nurture: An introduction to human behavioral genetics. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Ochs, Elinor. 1988. Culture and language development: Language acquisition and language socialization in a Samoan village. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. --- Ochs, Elinor, and Bambi Schieffelin. 1984. Language Acquisition and Socialization: Three Developmental Stories and Their Implications. In Culture Theory: Essays on Mind, Self, and Emotion. R. Shweder and R.A. LeVine, eds. Pp. 276-320. New York: Cambridge University. --- Schieffelin, Bambi B. 1990. The Give and Take of Everyday Life: Language Socialization of Kaluli Children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1

- ↑ SparkNotes Editors. (2006). SparkNote on Socialization. Retrieved April 2, 2012, from http://www.sparknotes.com/sociology/socialization/

- ↑ Levine, K. J., & Hoffner, C. A. (2006). Adolescents' conceptions of work: What is learned from different sources during anticipatory socialization?. Journal of Adolescent Research, 21, 647-669. doi: 10.1177/0743558406293963

- ↑ (Schaefer & Lamm, 1992: 113)

- ↑ Macionis, John J. "Sociology: 7th Canadian Edition". (Toronto: Pearson, 2011), 120-121

- ↑ Alvenfors, Adam (2010) Introduction - Integration? On the introduction programs’ importance for the integration of new employees http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:his:diva-4281

- ↑ Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. & Wanberg, C. R. (2003). Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling antecedents and their pathways to adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 779-794.

- ↑ Bester, G. (2007). Personality development of the adolescent: peer group versus parents. South African Journal of Education, 27(2), 177-190.

- ↑ Grier, Peter (24 April 2000). "The Heart Of A High School: Peers As Collective Parent". Christian Monitor News Science: 1.

- ↑ Grier, Peter (24 April 2000). "The Heart Of A High School:Peers As Collective Parent". Christian Science Monitor News Service: 1.

- ↑ Epstein, Marina & Ward, Monique L. (2011). Exploring parent-adolescent communication about gender: Results from adolescent and emerging adult samples. Sex Roles, 65, 108-118

- ↑ Rotherman, M., & Phinney, J. (1987). Introduction: Definitions and perspectives in the study of children's ethnic socialization. In J. Phinney & M. Rotherman (Eds.), Children's ethnic socialization: Pluralism and development (pp. 10-28). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Hughes, D., Rodriguez, J., Smith, E., Johnson, D., Stevenson, H. & Spicer, P. (2006). Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 5, 747-770.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 http://www.soc.ucsb.edu/faculty/baldwin/classes/soc142/scznDEF.html

- ↑ http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/social-institutions/ Stanford Encyclopaedia: Social Institutions

- ↑ Macionis, John J., and Linda M. Gerber. Sociology. Toronto: Pearson Canada, 2011. pg 116.

- ↑ Vaidyanathan, B. (2011). Religious resources or differential returns? early religious socialization and declining attendance in emerging adulthood. Journal for the scientific study of religion, 50(2), 366-387. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2011.01573.x

- ↑ Macionis, John J., and Linda M. Gerber. Sociology. Toronto: Pearson Canada, 2011. pg 113.

- ↑ Denhart, R. B., & Jeffress, P. W. (1971). Social learning and economic behavior: The process of economic socialization. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 30(2), 113-125.

- ↑ Harrington, Michael (2011) [1989]. Socialism: Past and Future. New York: Arcade Publishing. pp. 8–9. ISBN 1-61145-335-6.

- ↑ Arnett, J. J. (1995). Broad and narrow socialization: The family in the context of a cultural theory. Journal of marriage and family, 57(3), 617-628.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Poole, E. D. & Regoli, R. M. (1981). Alienation in prison: An examination of the work relation of prison guards. Criminology, 19 (2), 251-270.

- ↑ Carmi, A. (1983). The role of social energy in prison. Dynamische Psychiatrie, 16 (5–6), 383–406.

- ↑ Morita, N. (2009). Language, culture, gender, and academic socialization. Language and education, 23(5), 443-460.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 http://www.soc.ucsb.edu/faculty/baldwin/classes/soc142/sle&nsle

- ↑ Rushefsky, Mark E.; Patel, Kant (2006). Health Care Politics And Policy in America. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 47. ISBN 0-7656-1478-2. "...socialized medicine, a pejorative term used to help polarize debate"

- ↑ http://marxists.org/glossary/terms/s/o.htm#socialisation

Further reading

| Library resources about Socialization |

- Hurrelmann, Klaus (1989, reissued 2009) Social Structure and Personality Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McQuail, Dennis (2005) McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory: Fifth Edition, London: Sage.

- White, Graham (1977) Socialisation, London: Longman.

- Bogard, Kimber. "Citizenship attitudes and allegiances in diverse youth." Cultural Diversity and Ethnic minority Psychology14(4)(2008): 286-296.

- Mehan, Hugh. "Sociological Foundations Supporting the Study of Cultural Diversity." 1991. National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity and Second Language Learning.

- Bambi B. Schieffelin, Elinor Ochs. 1987. Language Socialization across Cultures. Volume 3 of Studies in the Social and Cultural Foundations of Language. Publisher Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521339197, 9780521339193

- Alessandro Duranti, Elinor Ochs, Bambi B. Schieffelin. 2011.The Handbook of Language Socialization, Volume 72 of Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics. Publisher John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 1444342886, 9781444342888

- Patricia A. Duff, Nancy H. Hornberger. 2010. Language Socialization: Encyclopedia of Language and Education, Volume 8. Publisher Springer, ISBN 9048194660, 9789048194667

- Robert Bayley, Sandra R. Schecter. 2003. Publisher Multilingual Matters, 2003 ISBN 1853596353, 9781853596353

- Claire Kramsch. 2003. Language Acquisition and Language Socialization: Ecological Perspectives .Advances in Applied Linguistics. Publisher Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003 ISBN 0826453724, 9780826453723

- Bambi B. Schieffelin. 1990. The Give and Take of Everyday Life: Language, Socialization of Kaluli Children. Publisher CUP Archive, 1990 ISBN 0521386543, 9780521386548

| ||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)